Eggert's sunflower (Helianthus eggertii)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 5/22/1997 | Recovery plan: 12/9/1999 |

Range: AL, KY, TN

SUMMARY

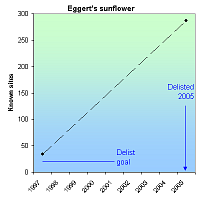

Eggert's sunflower was threatened by development, agriculture, herbicides and fire suppression. At the time of listing in 1997, there were 34 known sites for Eggert's sunflower. When delisted in 2005, there were 287 known sites, many of which were protected by cooperative management agreements.

RECOVERY TREND

Eggert’s sunflower (Helianthus eggertii) is an 8-foot tall sunflower that occurs in Alabama, Kentucky and Tennessee. It is commonly associated with the barrens-woodland ecosystem, a complex of somewhat dry plant communities maintained by drought and fire with a grassy ground cover and scattered medium-to-small-canopy trees [1].

The sunflower was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1997 due to habitat loss for residential, commercial and industrial development, plant succession, conversion of its limited habitat to pasture or croplands, and herbicide use, particularly along roadsides [1]. At the time of listing in 1997, it was known from 34 sites.

The 1999 Eggert’s sunflower federal recovery plan establishes the following delisting criteria: 1) The long-term conservation/protection of 20 geographically distinct, self-sustaining populations (distributed throughout the species’ range or as determined by genetic uniqueness) must be provided through management agreements or conservation easements on public land or land owned by private conservation groups, and 2) these populations must be under a management regime designed to maintain or improve the habitat and each population must be stable or increasing for five years.

Due to protection of known populations, discovery of new populations, and cooperative management agreements with a variety of agencies to protect the species, the sunflower was delisted in 2005, at which time there were 287 known sites and 73 defined populations [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1997. Determination of Threatened Status for Helianthus eggertii (Eggert’s Sunflower). 62 FR 27973.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Removal of Helianthus eggertii (Eggert’s Sunflower) from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants. 70 FR 48482.

Maguire daisy (Erigeron maguirei)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 9/5/1985 | Recovery plan: 8/15/1995 |

Range: UT

SUMMARY

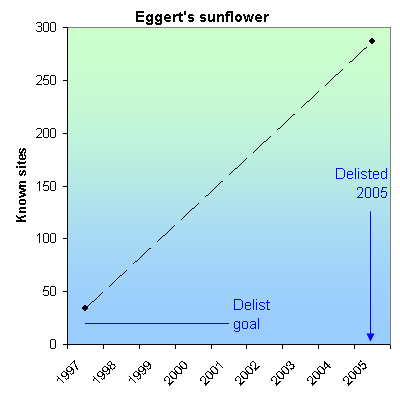

The Maguire daisy was listed as endangered in 1985 due to its population size and the threat uranium mining, oil and gas exploration, cattle grazing and recreation. Listing and interagency agreements abated the habitat threats. At the time of listing in 1985, the daisy was known from a single site and only seven individuals. By 1995 there were 32 known sites and an estimated population of 5,000. As of 2011, there were 118 known sites and an estimated 164,250 individuals.

RECOVERY TREND

The Maguire daisy (Erigeron maguirei) is a member of the sunflower family with dime-sized white or pinkish-white flowers. Its leaves and stems are covered with abundant stiff, course hairs, and bits of sand commonly cling to its leaves and stems. Its range is estimated at 390 square miles (1,010 square kilometers) and extends from the San Rafael Swell south through the Waterpocket Fold of Capitol Reef National Park in Utah [1]. The three largest populations, including over 91 percent of all known plants, occur primarily within Capitol Reef. One of these three populations (Deep Creek) also includes a small portion, less than 1 percent, of all the known plants, on national forest lands. The other six populations (Calf Canyon, Coal Wash, Secret Mesa, Link Flats, John’s Hole and Seger’s Hole) are managed primarily by the BLM. A portion of three of these six populations (Calf Canyon, Secret Mesa, and Link Flats) also occurs on Utah’s School and Institutional Trust Lands [1].

The daisy was listed as endangered in 1985 due to small known population size and the threat of surface-disturbing activities such as uranium mining, oil and gas exploration, cattle grazing, and recreation [3]. Only seven plants were known at the time, from a single site. The 1995 Recovery Plan called for 20 populations, the establishment of formal land management designations to provide for long-term undisturbed habitat, and the protection of habitat from the loss of individuals and from environmental degradation. At the time the Recovery Plan was written, the species was known from seven populations (32 sites) with the total population estimated at 5,000 [2]. In 2011 there were nine known populations at 118 sites. The Service determined that the 20 populations called for in the recovery plan was not necessary for recovery due to the broader distribution of the species than was known at the time and a greater chance of dispersal and persistence across its range based on the discovery of new sites. It was downlisted to threatened status in 1996, and in 2011 the total population was estimated at 164,250 individuals, so the species was delisted due to recovery [1,4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Removal of Erigeron maguirei (Maguire Daisy) from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants; Availability of Final Delisting Monitoring Plan. 76 FR 03029.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Recovery Plan for Maguire Daisy (Erigeron maguirei). 18 pp.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Determination of Endangered Status for Erigeron maguirei var. maguirei. 50 FR 36089.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Removal of Erigeron maguirei (Maguire Daisy) From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants. 76 Fed. Reg. 3029.

Mountain golden heather (Hudsonia montana)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 10/20/1980 | Listed: 10/20/1980 | Recovery plan: 9/14/1983 |

Range: NC

SUMMARY

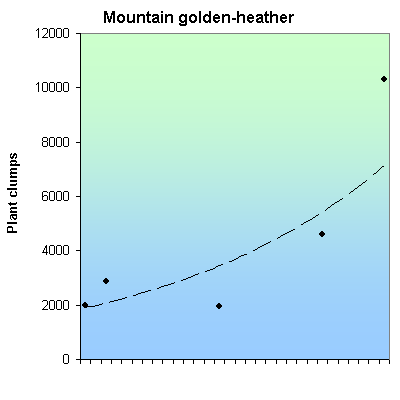

Mountain golden heather declined due to trampling by rock climbers and hikers, and due to fire suppression which allowed other species to dominate its limited habitat. Following protection under the Endangered Species Act, mountain golden heather increased from 2,883 plant clumps in 1982 to 10,301 in 2009.

RECOVERY TREND

Mountain golden heather (Hudsonia montana) is a flowering plant in the rock-rose family found only in two counties in western North Carolina. It is restricted to unusually dry specialized microhabitats [1].

The heather declined due to soil compaction and plant crushing by rock climbers and hikers, and vegetative crowding of limited habitat due to fire suppression [2].

It was discovered in 1816, thought extinct in the 1960s and early 1970s, rediscovered in 1978, and listed a threatened species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1980 and North Carolina in 1981 [4]. Critical habitat was designated in 1980 at the time of federal listing.

Prescribed burning, seedling reintroduction and control of recreation impacts have reduced threats and improve the species status [1]. As a result, the total mountain heather population increased from 2,883 plant clumps in 1982 to 10,301 in 2009 [1, 3].

CITATIONS

[1] Michener, R.L. 2004. Current global status of Hudsonia montana nuttall (Mountain Golden Heather). Senior research thesis, Whitman College.

[2] NatureServe. 2010. Mountain Golden Heather Species Profile. Available at: http:www.natureserve.org

[3] Alexander, M. 2011. Personal Communication with Mara Alexander, botanist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Asheville Field Office. Nov. 2, 2011.

[4] U.S Fish and Wildife Service. 1983. Mountain Golden Heather Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, Georgia, 26 pp.

Robbins' cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 9/17/1980 | Listed: 9/17/1980 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: NH(b) ---

SUMMARY

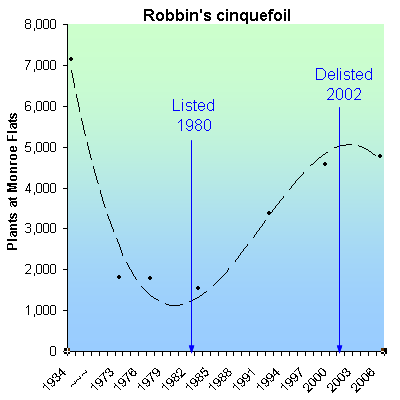

Robbin's cinquefoil, a member of the rose family, is endemic to the Presidential Range in New Hampshire's White Mountains where it was nearly driven to extinction due to trampling and erosion from hikers on the Appalachian Trail. Following its 1980 endangered listing, the trail was rerouted by volunteers, the critical habitat was closed to entry, and a propagation and reintroduction program was established. The largest population increased from 1,547 in 1983 to 4,777 in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

Robbins' cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana), also known as dwarf cinquefoil, is a small perennial member of the rose family endemic to Mt. Washington and Franconia Ridge within White Mountains National Forest in New Hampshire. When the species was placed on the endangered species list in 1980, only two populations were known — a natural population at Monroe Flats and an introduced population at Camel Patch [1]. The primary threat was recreational impacts associated with the Appalachian Trail at Monroe Flats. Excessive collection had previously been a threat, but was largely controlled by 1980.

Monroe Flats was designated as critical habitat, the path through it relocated, and additional populations were established through reintroductions. In 2002, three of four populations were considered viable, and Robbins' cinquefoil was declared recovered and removed from the endangered species list [1].

MONROE FLATS

Monroe Flats is windswept saddle just above the tree line between Mt. Monroe and Mt. Washington in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains National Forest. It is connected to Crawford Notch, a tourist destination, by the Crawford Path. Able Crawford homesteaded White Mountain Notch (now known as Crawford Notch) in 1793, commencing a three-generation family development of the mountain's first trails, roads, turnpikes, hotels and taverns. The Crawfords, however, "appear not to have been astute business men and most of their ventures turned out to be financial disasters" [6]. Able's son, Ethan Allen, would eventually be consigned to debtor's prison. Able's farm and Mt. Crawford Tavern would be foreclosed upon shortly after his death. But prior to that, the Crawford's housed, fed, watered, entertained and guided tourists who came to Crawford Notch on roads and turnpikes they lobbied for, invested in, and helped construct. To ease access to the summit of the White Mountains, Able built the Crawford Path in 1819. Now part of the Appalachian Trail, it is the longest continually used hiking path in the United States.

The Crawford Path bisected the Monroe Flats population of Robbins' cinquefoil [5]. Ironically, the plant itself was not discovered until five years later by Thomas Nuttall, and perhaps would not have been, had it not been located along the very trail that nearly drove it extinct. The path was not heavily used over the next 150 years, though Thomas Cole and other painters flocked to the area following the Willey Family tragedy of 1826, creating White Mountain art, an offshoot of the Hudson River School, projecting the White Mountains landscape into the 19th-century American psyche, and ensuring a steady stream of tourists to Crawford Notch to this day. [7].

The plant's population coexisted with the path for many decades, but with the post-1950 human population boom and increased popularity of wilderness recreation in the 1960s and 70s, the stage was set for its demise. It occurred to the east and east of the path through at least 1962, but was extirpated from the west side and within eight feet of the trail in 1972 [5]. The population was approximately 1,800 plants (> 1.4 cm wide) in 1973 and 1977 [1, 5], just a quarter of its size in 1934 [5]. By 1983, it had declined to 1,547 plants in this size class [1].

After Robbins cinquefoil was listed as an endangered species with critical habitat in 1980, the Appalachian Mountain Club rerouted Crawford's Path around the designated critical habitat zone and built a scree wall alongside to hinder entrance [1, 2]. The U.S. Forest Service prohibited entry into the critical habitat and educated hikers about the importance of staying on trail. The New England Wildlife Flower Society propagated and reintroduced plants within and between populations. In response, Robbins' cinquefoil increased to 4,575 in 1999 [1] and 4,777 in 2006 [4]. Counting plants of all sizes, the total population in 1999 was about 14,000 plants.

FRANCONIA RIDGE I

Located 18.6 miles to the west of Monroe Flat, Franconia Ridge supports the only other natural population of Robbins cinquefoil. A single plant was rediscovered there in 1984 [1]. As of 2002, it numbered fewer than 50 plants growing in crevices on a vertical cliff and was not considered viable. It is believed to be a remnant of a larger population that has been largely extirpated due to recreation-related erosion.

Prior to 1980, unsuccessful attempts were made to establish transplanted populations at roughly 20 different sites [1]. In the 1990s the New England Wild Flower Society, with the help of the Appalachian Mountain Club, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Forest Service, began a successful propagation program [2].

FRANCONIA RIDGE II

This population was established on Franconia Ridge with transplants in 1988, 1989 and 1996 [1]. It has fluctuated in size, but the number of plants with a rosette diameter greater than 1.4 centimeters was 331 in 1999, 307 in 2000, and 331 in 2001.

CAMEL PATCH

Robbins cinquefoil was successfully introduced to Camel Patch prior to 1980 [1]. It was augmented with an unknown number of plants from the 1980s to 1991, and more systematically from 1999 forward. The population has remained small but stable, with 84 plants in 1984, 87 in 1999, 101 in 2000, and 97 in 2001.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Removal of Potentilla robbinsiana (Robbins’ cinquefoil) from the federal list of endangered and threatened plants. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 27, 2002 (67 FR 54968).

[2] Brumback, W.E., D.M. Weihrauch, and K.D. Kimball. 2004. Propagation and transplanting of an endangered alpine species: Robbins' cinquefoil, Potentilla robbinsiana (Rosaceae). Native Plants Journal 5(1):91-97.

[3] Weihrauch, D. 2005. Personal communication with Doug Weihrauch, ecologist, Appalachian Mountain Club, December 2, 2005.

[4] Riely, A. 2008. The Return of the dwarf cinquefoil. Excerpted from Appalachia! Available online at http://gullivers-nest.blogspot.com/2008/01/return-of-dwarf-cinquefoil.html. Accessed September 28, 2011.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Forest Service. 1983. Robbins' cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana) recovery plan.

[6] Russac. R. 2012. The Crawford Family. In WhiteMountainHistory.org: Telling the story of 200 years of White Mountain History. Available at http://whitemountainhistory.org/The_Crawford_Family.html

[7] Wikipedia. 2012. White Mountain art. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Mountain_art.

San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 8/11/1977 | Recovery plan: 1/26/1984 |

Range: CA

SUMMARY

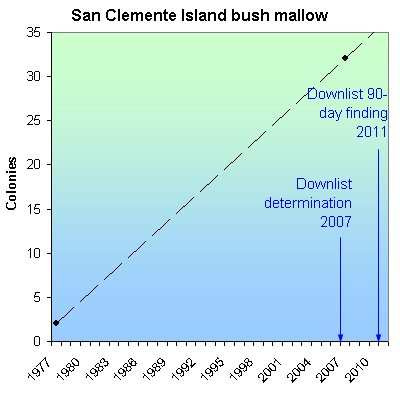

The San Clemente Island bush mallow declined due to overgrazing by introduced sheep, goats and pigs. Removal of the animals has allowed it to rebound, but it remains threatened by military training activities, erosion, invasive plants and fire. At the time of listing in 1977, only one to two plant colonies plant were known to survive. By 2007, 32 were known.

RECOVERY TREND

The San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus) is endemic to California’s San Clemente Island [1]. It is a rounded, evergreen shrub with inflorescences of crowded, pink flowers [1]. It was discovered in 1923 growing on the walls of a single canyon [2]. Later, another eight to 10 clumps of 15 to 20 individuals were discovered on the walls of other canyons [2]. Grazing by feral sheep, goats and pigs introduced to the island in the late 1800s damaged native vegetation [3] and left bush mallow plants only in places inaccessible to the feral animals [2].

In 1962, programs to eradicate feral animals on the island were initiated by the Navy, which in 1934 acquired the island for a military training facility [3]. These efforts were unsuccessful, but renewed efforts in the 1980s led to the extirpation of feral animals on the island in 1992 [3]. Since the Navy’s eradication efforts, native vegetation has begun to recover [1]. Bush mallow habitat in one canyon, however, is in a bombing impact zone [1]. This poses a potential direct threat to the plants and could cause increased threat from erosion [1].

At the time of listing in 1977, there were only two known colonies. The removal of feral goats and pigs has allowed the population to increase, and as of 2007, 30 new occurrences were known. In the 2007 Five-Year Review, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended downlisting the plant [4], and in 2011 the Service issued a positive 90-day finding on a petition to downlist the bush mallow [5]. In 2012, however, the Service determined that the plant should not be downlisted because it continues to be threatened by military activities, erosion, nonnatives, fire, climate change, and low genetic diversity [6].

CITATIONS

[1] California Department of Fish and Game. 2004. The Status of Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals and Plants of California. Sacramento, CA. Available at <http://www.dfg.ca.gov/hcpb/species/t_e_spp/t_eplants.pdf>.

[2] Where Have All the Wildflowers Gone? A Region-by-Region Guide to Threatened or Endangered U.S. Wildflowers. Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc. NY.

[3] Helenurm, K., R West, and S.J. Burckhalter. 2005. Allozyme Variation in the Endangered Insular Endemic Castilleja grisea. Annals of Botany 95(7):1221-1227.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Malacothamnus clementinus (San Clemente Island Bush Mallow) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office. 30 pp.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. 90-Day Finding on a Petition to Delist or Reclassify From Endangered to Threatened Six California Species. 76 FR 03069.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. 12-Month finding on a petition to downlist three San Clemente Island plant species. Advance notice. May 15, 2012. Available at:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2012-11339.pdf.

San Clemente Island lotus (Lotus dendroideus var. traskiae )

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 8/11/1977 | Recovery plan: 1/26/1984 |

Range: CA

SUMMARY

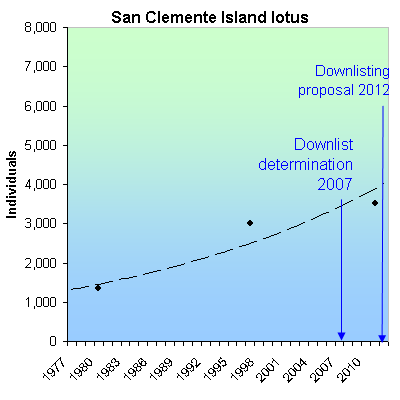

The San Clemente Island lotus became endangered due to overgrazing. Following its listing as an endangered species in 1977, feral ungulates were eradicated from the island, but military training and invasive species remain a threat. This plant has increased from 1,340 individuals in nine sites in 1980 to 3,525 individuals in 29 sites in 2011. A proposal to downlist the lotus from "endangered" status to "threatened" status was issued in 2012.

RECOVERY TREND

San Clemente Island lotus (Acmispon dendroideus var. traskiae), formerly called San Clemente Island broom, is endemic to California’s San Clemente Island, where it grows on open, grassy slopes and hillsides.

Populations declined drastically following the introduction of domestic and feral herbivores to the island, leading to listing as an endangered species in 1977. By 1993 feral ungulates had been eradicated, leading to a dramatic rebound and a recommendation by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to downlist the species to "threatened" status in 2007 [1] and a proposal to downlist in 2012 [3]. The plant remains threatened by military training activities, erosion and invasive species [2].

The earliest published information regarding population size for the lotus states that nine occurrences and 1,340 individuals were present on the island in 1980. As of 2011 the total number of plants was estimated at 3,525 in 29 sites [3].

The original range and distribution of the lotus on San Clemente Island is speculative because its decline began before thorough surveys were conducted. Occurrence data now spans the length of the island, with the species range including north-facing slopes over most of the eastern and western sides of the island [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Lotus dendroideus var. traskiae (San Clemente Island lotus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, Carlsbad, California. 24 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. 90-Day Finding on a Petition To Delist or Reclassify From Endangered to Threatened Six California Species. January 19, 2011. 76 FR 03069.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. 12-Month finding on a petition to downlist three San Clemente Island plant species. Advance notice. May 15, 2012. Available at:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2012-11339.pdf.

San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 8/11/1977 | Recovery plan: 1/26/1984 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

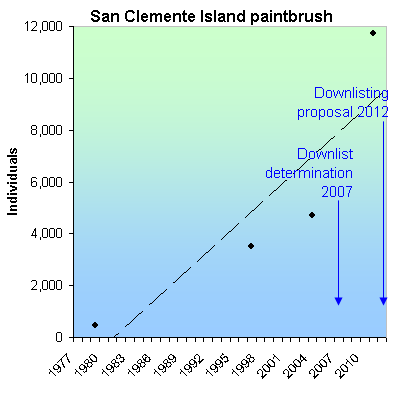

The San Clemente Island paintbrush declined in the middle of the last century, largely due to grazing and trampling by feral goats and pigs. Since being listed as an endangered species in 1979, its population increased from 500 plants to 11,733 in 2011. In 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed downlisting the paintbrush from “endangered” to “threatened” status.

RECOVERY TREND

The San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea) is one of 13 plant species endemic to the Island of San Clemente, Calif. [1]. The San Clemente Island paintbrush is a somewhat shrubby plant with yellow blooms [2] associated with the sage scrub community on the island [3]. It is likely partially parasitic on shrubs in the “goldenbrush” family [3].

The decline of the San Clemente Island paintbrush was primarily due to grazing and trampling by feral goats and pigs [1]. Livestock were eliminated from the island prior to the establishment of a military training facility in the 1930s, but some feral goats and pigs remained and their populations increased dramatically [4]. Plants that survived the increase in grazing and trampling tended to be located on steep cliff faces which goats and pigs could not easily access [1].

In 1939, a collector described the San Clemente Island paintbrush as common on the lower slope of bluffs on the southeast coast of the island [2]. By 1963 it had declined to the point of being described as “occasional on the southeast coast and rare on canyon-sides elsewhere” [2]. An effort to remove feral animals from the island was initiated in 1962, but was unsuccessful [4]. By 1978 few paintbrushs could be found [2]. A survey of the entire island conducted in 1979 found a total of 450 plants [2].

Following the paintbrush's listing as an endangered species in 1979, efforts were renewed to remove goats and pigs, resulting in their extirpation in 1992 [4]. Following the elimination of these animals, paintbrush populations began to increase and expand [4]. In 1996 and 1997, 77 populations of San Clemente Island paintbrush were mapped on the island, totaling more than 3,500 plants [5]. In 2003 and 2004, surveyors mapped an additional 42 locations and 1,120 individuals [6]. Occurrences ranged from isolated plants to 200 individuals. These new occurrences were mainly concentrated in steep canyons on the western side of the island, although a few were discovered near previously recorded individuals in the eastern canyons. Taken together, these two surveys suggest that Castilleja grisea can currently be found in approximately 119 locations on San Clemente Island [6]. In 2011 the total number of plants was estimated at 11,733 [7].

In the 2007 Five-Year Review, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended downlisting the paintbrush from "endangered" to "threatened" status [6]. The Service issued a proposal to downlist the paintbrush in May 2012 [7].

CITATIONS

[1] Center for Plant Conservation. CPC National Collection Plant Profile: Castilleja grisea. Website <http://www.centerforplantconservation.org/ASP/CPC_ViewProfile.asp?CPCNum=817> accessed January, 2005.

[2] Mohlenbrock, R.H. 1983. Where Have All the Wildflowers Gone? A Region-by-Region Guide to Threatened or Endangered U.S. Wildflowers. Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc. NY.

[3] Endangered Species Information System. 1996. Fish and Wildlife Information Exchange, VA Tech. San Clemente Island Indian Paintbrush. Website <http://fwie.fw.vt.edu/WWW/esis/lists/e701029.htm> accessed January, 2005.

[4] Helenurm, K., R West, and S.J. Burckhalter. 2005. Allozyme Variation in the Endangered Insular Endemic Castilleja grisea. Annals of Botany 95(7):1221-1227.

[5] Junak S.A. and D.H. Wilken. 1998. Sensitive plant status survey, Naval Auxiliary Landing Field, San Clemente Island, California. Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Castilleja grisea (San Clemente Island Indian Paintbrush) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office. 21 pp.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. 12-Month finding on a petition to downlist three San Clemente Island plant species. Advance notice. May 15, 2012. Available at:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2012-11339.pdf.

Sandplain gerardia (Agalinis acuta)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 9/7/1988 | Recovery plan: 9/20/1989 |

Range: CT(b), MD(b), MA(b), NY(b), RI(b) ---

SUMMARY

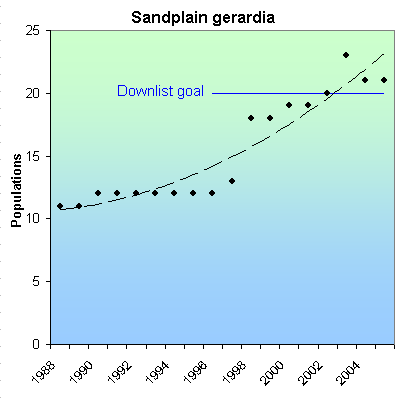

The sandplain gerardia is threatened by the ongoing loss of its coastal grassland habitats due to development. Also, the loss of grazing animals and the suppression of fires have allowed woody vegetation to claim many of its historical sites. When the sandplain gerardia was listed as endangered in 1988, only 12 of 51 historic populations remained. As of 2005 there were 22 populations, as well as an increase in the total number of plants.

RECOVERY TREND

The sandplain gerardia (Agalinis acuta) inhabits dry, sandy, poor-nutrient soils in sandplain and serpentine sites in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York and Maryland [1]. Its favored growing conditions are native grasslands on sandy loam soils. It requires exposed mineral soil in close proximity to little bluestem and other native grasses, with which it is thought to form hemiparasitic root connections [12]. Most sites are within 10 miles of the coast. The taxonomic relationship between A. acuta and the nonendangered A. tenella is unclear. They are morphologically distinct, but chloroplast DNA variation is not significant [11].

Fifty-one populations were known historically (two more than reported in the 1989 federal recovery plan), but only 12 remained when the gerardia was placed on the endangered species list in 1988. Reintroductions increased the number of occupied populations to 22 in 2005. Short-term population trends can be misleading because of the species' capacity for explosive population growth and rapid decline. Populations in all states except Rhode Island grew substantially between 1988 and 2005. Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York populations were stable to moderately increasing between 1988 and the late 1990s, increasing significantly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, growing explosively for one or several years, then rapidly declining in 2004-2005. There are indications of a similar pattern in Maryland, but adequate data are not available. The small Rhode Island population fluctuated substantially with an overall stable trend. Cumulatively, the MA, RI, CT and NY populations increased dramatically from means of 4,441 (1988-1993) to 14,069 (1994-1999) to 196,466 (2000-2005).

MASSACHUSETTS. The sandplain gerardia historically occurred in 24 populations on Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard and a few disjunct populations as far west as Worcester County [1]. Its decline was so complete that it was thought extinct in the state until rediscovered on Cape Cod in 1980. When placed on the endangered species list in 1988, just two populations were known in historic cemeteries in Sandwich and Falmouth [3]. A third population was discovered on Martha's Vineyard in 1994 [3]. Due to intensive management, including scientific research, reintroductions, habitat protection and habitat management, the Massachusetts population grew remarkably. From 1988 to 1991 it declined from 13,977 plants to 150, steadily increased to 23,161 in 1998, then exploded to about 483,530 in 2004, before declining to about 49,063 in 2005. The 2005 decline is believed to be drought related [4].

The Sandwich population fluctuated greatly, but increased significantly between 1988 (9 plants) and 2005 (2,299) [3]. High points were in 1995 (4,253), 2000 (4,757) and 2003 (3,712). The population only dipped below 1,000 plants twice between 1993 and 2005. The Falmouth population was discovered in 1981 and supported 6,994 plants in 1988. It was augmented with an introduced subpopulation on an adjacent site beginning in 1989. It declined to less than 50 plants in 1991 and 1992, steadily increased to 4,476 in 1999, exploded to 231,600 in 2004, then plummeted to 21,262 in 2005. A third natural population was discovered on Martha's Vineyard in 1994. It increased steadily from 378 in 1994 to 1,315 in 2000, then jumped to more than 4,200 in 2002-2004, before declining to 1,309 in 2005.

Three populations were introduced in 1998 and 2000 [3]. The Falmouth population increased steadily from 552 plants in 1998 to 15,000 in 2004, then declined to 1,910 in 2005. One Martha's Vineyard reintroduction increased from five plants in 1998 to 1,092 in 1994. A second Martha's Vineyard reintroduction increased from 23 plants in 2000 to 1,238 in 2003. Prior to these successes, there were "several" failed reintroduction attempts on Nantucket and a "couple" on Martha's Vineyard [4]. Introduced populations, including the Falmouth subpopulation, often made up 40-50 percent of the total state population in the last decade.

RHODE ISLAND. The sandplain gerardia historically occurred in six populations in Rhode Island, but by 1988 was reduced to just a single population of 56 plants in a historic cemetery [1]. The population fluctuated considerably, but without discernable trend between 1988 and 2005 [5]. A second population of 33 plants was established in 2003 and grew to 241 plants in 2005.

CONNECTICUT. By 1988, the sandplain gerardia was extirpated from the only two known sites in Connecticut [1], but a very small population was discovered in 1990 [6]. It fluctuated between zero and 32 observable plants from 1990 to 2002, then due to better site management, increased to 165 plants in 2004 before declining to 84 in 2005.

NEW YORK. The sandplain gerardia formerly occurred in 17 populations in New York [1]. The Montauk, Long Island population alone was said to have once had "untold millions" of plants [2]. At the time of listing, only six populations remained in New York with a total population of 814 plants [10]. Cumulatively, the populations remained relatively stable until 1997 (approx. 500-2,000 plants), grew substantially through 2002 (7,272 plants), exploded to 83,531 in 2003, and declined to 10,488 in 2005. Reintroductions were attempted at seven locations after 1988. Of these, four were successful with a mean of 96-263 plants. Plants sown at new introduction sites, and at unoccupied locations within existing sites, accounted for 61-94 percent of total plants in New York from 2001-2005.

MARYLAND. Maryland supported two historical gerardia populations, one of which was destroyed by urbanization and highway construction prior to 1988 [4]. At the time of listing, a single population of 150 plants existed at Soldiers Delight Natural Environmental Area within Patapsco Valley State Park. The population has not been augmented, but due to an active program of burning, clearing, mowing and eradication of exotic plants, the Soldiers Delight population increased to 10,000 in 1989 and well over 100,000 by 2005 [2]. More detailed annual population estimates are not available, but the population presumably fluctuates significantly between these extremes. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources describes the population as stable or increasing, but cautions that additional monitoring is needed to establish a scientifically defensible trend [8]. A second potential population was discovered at Andrews Air Force Base in 1993 but could not be relocated in 1995 [9]. However, specimens could not be distinguished from A. obtusifolia and A. decemloba and thus may not be the sandplain gerardia.

The 1989 federal recovery plan [1] requires 1) The establishment or discovery of 20 stable, wild populations located throughout the species' historic range. To be "stable," a population must have a continuous five-year geometric average of at least 100 plants. 2) At least 15 of the populations must be on protected lands. 3) There must be proven technology for propagation or seed storage. As of December 2005, 13 populations had a five-year mean of at least 96 plants.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1989. Sandplain gerardia (Agalinis acuta) recovery plan. Newton Corner, MA. 47 pp.

[2] NatureServe. 2005. Central database. NatureServe, Arlington, VA.

[3] Somers, P. 2005. Agalinis acuta data summaries, 1980-2005. Spreadsheets provided by Paul Sommers, Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, Westborough, MA, November 2005.

[4] Somers, P. 2005. Personal communication with Paul Somers, Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, Westborough, MA, November 17, 2005

[5] Raithel, C. 2005. Personal communication with Christopher Raithel, Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered Species Program, Providence, RI, November, 2005.

[6] Murray, N. 2005. Personal communication with Nancy Murray, Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, Wildlife Division, November 22, 2005.

[7] Thomas, J. 2004. Endangered Plants of Maryland: Sandplain Gerardia. Maryland Department of Natural Resources website (www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/rtesandplain.asp) dated 10-25-04.

[8] Tyndall, W. 2005. Personal communication with Wayne Tyndall, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Annapolis, MD, November 23, 2005.

[9] Davidson, L. 2005. Personal communication with Lynn Davidson, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Annapolis, MD, November 28, 2005.

[10] Jordan, M. 2005. Agalinis acuta monitoring data, Long Island, New York. Spreadsheet provided by Marilyn Jordan, The Nature Conservancy, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, November, 2005

[11] Neel, M.C. and M.P. Cummings. 2004. Section-level relationships of North American Agalinis (Orobanchaceae) based on DNA sequence analysis of three chloroplast gene regions. BMC Evolutionary Biology 4:15.

[12] Jordan, M. 2006. Personal communication with Marilyn Jordan, The Nature Conservancy, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, February 13, 2006.

Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/7/1993 | Recovery plan: 11/12/1996 |

Range: DE(b), MD(b), NY(b), NJ(b), NC(b), SC(b), VA(b) --- CT(x), MA(x), RI(x)

SUMMARY

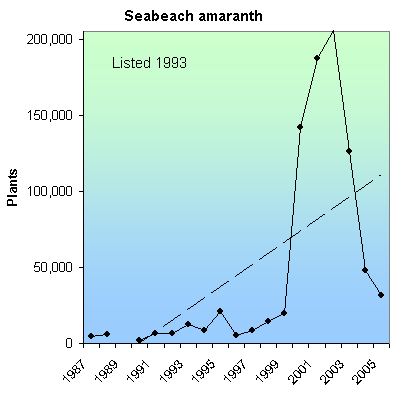

By 1988, seabeach amaranth had been extirpated from much of the Atlantic coast, largely due to beach development, dune stabilization and enhancement projects, off-road vehicles, recreation, exotic species and hurricanes. Since being placed on the endangered species list in 1993, the amaranth has recolonized New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia, and has increased from approximately 13,000 at listing to about 31,000 as of 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

The seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) is endemic to beaches on the Atlantic coast from Cape Cod, Mass., to Kiawah Island along the central South Carolina coast [1]. It occurs on sparsely vegetated overwash flats and fore dunes, often around inlets on barrier island ends. Hurricanes and storms reduce and eliminate populations, but also create new habitat by reducing competing ground cover. They may also aid large-scale dispersal. The amaranth traps sand, initiating dune formation and creating suitable habitat for other plants, such as sea oats and beach grass. Numerous shorebirds, including the least tern (Sterna antillarum), Wilson's plover (Charadrius wilsonia), black skimmer (Rhynchops niger), Caspian tern (Sterna caspia), and the endangered piping plover (Charadrius melodus) and roseate tern (Sterna dougallii dougallii), nest in seabeach amaranth stands [2].

The amaranth formerly occurred in 31 counties in nine states, from Massachusetts to South Carolina [1]. By 1988, it occurred only in North and South Carolina. Its decline was likely caused by beach development, dune stabilization and enhancement projects, off-road vehicles, recreation, exotic species and hurricanes. Severe weather in 1989 and 1990 (Hurricane Hugo, Hurricane Bertha, northeasters) caused the South Carolina population to decline by 90 percent (1,800 plants in 1988, 188-379 plants in 1990).* At the same time, 13 populations recolonized Long Island, N.Y., perhaps carried by the storms. Even with the inclusion of the Long Island populations, the species declined by 76 percent between 1988 and 1990. Since being placed on the endangered species list, the amaranth has recolonized New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. Annual population counts were not consistently made in South Carolina, but in the other six states, it increased dramatically from 14,899-17,174 in 1993 to 46,108-48,668 in 2004. While the species fluctuated dramatically (well over 100,000 plants in 2000, 2001, 2003 and fewer than 50,000 in 1999, 2002 and 2004), the trend between 1993 and 2004 was clearly upward.

New Jersey. Extirpated in 1913 [1]; recolonized in 2000 at four sites within Gateway National Recreation Area and several sites on Monmouth County municipal beaches [3]. The latter sites were created by a 1995 beach nourishment project by the Army Corps of Engineers. The 2000 population was 1,039; the 2005 population was 5,795-5,813 [5].

Delaware. Extirpated in 1875 [1]; recolonized in 2000 between the north end of Delaware Seashore State Park and Fenwick Island State Park [6]. The 2000 population of 32 plants grew to 423 in 2002, but declined to just six in 2005 [6, 7]. Some of the plants were found in protected piping plover nest areas [6]. There was no obvious change in habitat conditions that would explain the dramatic decline; it may reflect a natural population fluctuation [7].

Maryland. The amaranth was first found in 1967 at Assateague Island National Seashore in storm overwash areas, but was extirpated, probably due to failed Park Service dune construction and stabilization efforts in 1973 [1]. Two plants naturally recolonized the seashore in 1998 — the first sighting of the species between New York and North Carolina in 26 years. With Hurricane Bonnie approaching, the U.S. Park Service and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources removed one of the plants and took cuttings from the other. The cutting did not seed, and the wild plant was killed by Bonnie. The captured plant produced thousands of seeds, and some 5,400 of their greenhouse-raised offspring were outplanted between 2000 and 2002. The population increased to about 870 in 2001 and 2002, then stabilized at 480-560 plants in 2003-2005 [8].

Virginia. Extirpated in 1973 [1]; recolonized in 2001 with 10 plants, probably dispersers planting at Assateague Island National Seashore [8]. The population fluctuated without apparent trend and was at 30 plants in 2005.

New York. Extirpated about 1960 [1]. Recolonized in 1990 with 331 plants and increased to about 190,500 plants in 2002 before declining to 30,831 in 2004 [9]. Most amaranth sites are within areas symbolically fenced to protect endangered piping plovers.

North Carolina. The North Carolina population fluctuated significantly with lows of 490 (1991), 710 (1999), and 183 (2000) and highs of 29,993 (1992), 38,702 (1995) and 21,966 (2005) [10].

South Carolina. Amaranth populations declined from 1,334 in 1987 to zero and four plants in 1999 and 2000 [1, 10], but the population sizes in 2003 (1,381) and 2004 (2,110) were similar to the 1987 count [11]. The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources transplanted nearly 4,000 seedlings from greenhouses to barrier-island beaches in 2000-2001.

* There are minor discrepancies between reported counts in some years, likely due to a confusion of preliminary and final counts, timing of surveys, etc. [10]. We report the data as a range between the different reports. In all such cases, one of the numbers was provided by Dale Suiter of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Service is in the process of systematizing the data and running statistical analyses.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Amaranthus pumlius (Seabeach Amaranth) determined to be threatened. April 7, 1993 (58 FR 18035).

[2] Randall, J. 2002. Bringing back a fugitive - seabeach amaranth. Endangered Species Bulletin, July-August 2002.

[3] Walsh, W. 2000. Regional News & Recovery Updates: Region 5. Endangered Species Bulletin, September, 2000.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1996. Recovery Plan for Seabeach Amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) Rafinesque. Atlanta, Georgia.

[5] Staples, J.C. 2005. Personal communication with John C. Staples, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Jersey Field Office, November 21, 2005.

[6] Pepper, M. 2004. 2004 Amaranthus pumilus (Seabeach amaranth) Survey Results. Unpublished report, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

[7] McAvoy, W. 2005. Personal communication with William McAvoy, Botanist, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, November 7, 2005.

[8] Sturm, M. 2005. Personal communication with Mark Sturm, Assateague Island National Seashore, November 14, 2005.

[9] Young, S. 2005. Amaranthus pumilus Counts on Long Island 1990-2005. New York Natural Heritage Program Information.

[10] Suiter, D. 2005. Personal communication with Dale Suiter, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Raleigh, NC, December 7, 2005 and February 22, 2006.

[11] Strand, A. 2005. Seabeach Amaranth 2004 census and seed rain estimates. Unpublished report, College of Charleston, Charleston, S.C.

[12] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Seabeach Amaranth (Antaranthus pumilus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Raleigh, N.C.

Small whorled pogonia (Isotria medeoloides)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 9/9/1982 | Recovery plan: 11/13/1992 |

Range: CT, DC, DE, GA, IL, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, NC, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, SC, TN, VA, VT, WV, OH

SUMMARY

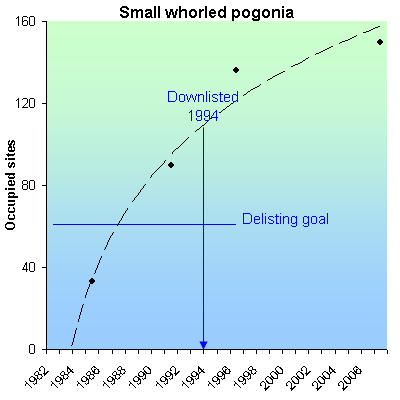

The small whorled pogonia is threatened by loss of forest habitat to residential development and roads, trampling, grazing and closure of forest canopies. Many populations are vulnerable to extinction because of their small size. It was listed as endangered in 1982 and downlisted to "threatened" status in 1994. Known sites increased from 33 in 1985 to 150 in 2007.

RECOVERY TREND

The small whorled pogonia (Isotria medeoloides) is a rare orchid of relatively open eastern deciduous and coniferous forests [1].

It formerly occurred in 48 counties in 16 states and Canada. When placed on the endangered species list in 1982, it was thought to exist in only 17 counties in 10 states and at one site in Ontario, Canada. By 1985 it was known from 34 sites, by 1991, 86 sites in 15 states, and by 1993 it was known from 104 sites in 15 states. The 104 sites included 66 in the Appalachian Mountains in New England and northern coastal Massachusetts ((Maine (17), New Hampshire (42), Massachusetts (five), Rhode Island (one), Connecticut (10)), 13 in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont ((New Jersey (three), Delaware (one), Virginia (nine)), 18 in the Southern Appalachians ((North Carolina (five), South Carolina (four), Georgia (eight), Tennessee (one)) and seven disjunct populations ((Pennsylvania (three), Ohio (one), Michigan (one), Illinois (one), Ontario (one)).

Since 1993, additional small populations were discovered in the southern portion of the pogonia's range, and in New Hampshire and Maine [4]. In 1999, a new population was documented for the first time in West Virginia, but it remained extirpated from Vermont, New York, Maryland, Missouri and the District of Columbia. As of 1998, plants had not been found at the Ontario site since the sighting of a single individual in 1989 [3]. As of 2008, the species was known to occur at 150 sites [5]. In 2010 it was rediscovered in Schunnemunk Mountain State Park, New York [6].

The 1992 revised recovery plan stipulates that downlisting to "threatened" status should be initiated when 25 percent of the viable populations known as of 1992 are protected, and proportionally distributed throughout the species' range [2]. The species was downlisted to “threatened” in 1994 based on finding that 23 percent of all sites were viable and protected, and 62 percent of viable populations were protected [1].

Delisting is to be initiated when there at least 61 sites which 1) are permanently protected; 2) represent at least 75% of self-sustaining populations over a ten-year period; and 3) management commitments or sufficient habitat exist to allow existing sites to expand. In its 2008 Five-Year Review, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that the three additional criteria had not been met, but that the species was “on the brink of recovery.” The agency recommended updating the recovery plan delisting criteria based on improved understanding of the species' natural history.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Final rule to reclassify the plant Isotria medeoloides (small whorled pogonia) From endangered to threatened. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. October 6, 1994 (59 FR 50852-50857).

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Small whorled pogonia (Isotria medeoloides) Recovery plan. Hadley, MA.

[3] White, D.J. 1998. Update COSEWIC status report on the Small Whorled Pogonia Isotria medeoloides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa.

[4] U.S. Marine Corps. Small whorled pogonia (Isotria medeoloides). Poster available at (www.fws.gov/endangered/photos/posters/Pogonia.pdf)

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Small Whorled Pogonia (Istotria medeoloides) 5- Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. New England Field Office, Concord, NH. 26 pp.

[6] Smith, K. J. and S. Young. 2011. Rediscovery of Two Federally Listed Rare Plant Species in New York. Northeast Natural History Conference 2011. Available at http://nysparks.com/environment/documents/presentations/RediscoveryOf2FederallyListedRarePlantSpeciesInNY.pdf.

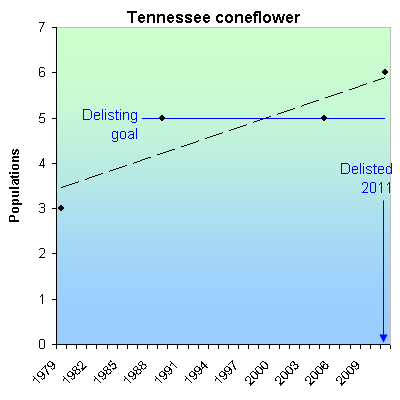

Tennessee coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/6/1979 | Recovery plan: 11/14/1989 |

Range: TN

SUMMARY

The Tennessee coneflower was listed as endangered in 1979 due to loss of habitat for residential and recreational development, succession of cedar glade communities and grazing. In 1979 there were three known populations, and in 1989 there were five populations. In 2011 the species was removed from the endangered list, with six populations and an estimated 107,349 total flowering stems.

RECOVERY TREND

The Tennessee coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis) is a large, showy, purple perennial restricted to cedar glades in a 154-square-mile section of central Tennessee near Nashville [1, 16]. Cedar glades are forest openings created when limestone approaches the earth's surface, leaving a thin layer of soil incapable of supporting trees or large shrubs. They are hotter and drier than the surrounding forest during the summer, and wetter during the winter and spring. Their unique conditions have promoted the evolution of 19 cedar glade endemics.

The Tennessee coneflower is naturally rare, but habitat destruction has further reduced its population size [1].

It was placed on the federal endangered species list in 1978. Due to the establishment and discovery of new populations, the expansion of existing populations, development of successful propagation techniques, and increased protection for all populations, the species has been under consideration for downlisting to threatened status since 1997, and was delisted in 2011 [13, 16].

As of 2011, there were six populations and 35 colonies made up of an estimated 107,349 total flowering stems [16]. Some of the natural populations have been augmented with introduced subpopulations. There is one whole introduced population and several cultivated sites that are not considered "populations" for conservation purposes.

Vine Population. This is the largest population and contains the largest unprotected subpopulation [2]. The public portion of the population occurs within the 35-acre Cedar Glade Natural Area of the Cedars of Lebanon State Forest [9]. The state natural area was designated in 2000 and is jointly managed by the Tennessee Division of Forestry and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Natural Heritage. Vine's largest subpopulation is Gattinger's Glade (also known as Harding Glade) within the Gattinger's Cedar Glade and Barrens Natural Area [x]. This 57-acre conservation easement was designated as a state natural area in 2003 as part of a mitigation plan for the development of the Nashville SuperSpeedway [3]. It was fenced with funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and is jointly managed by the Nashville SuperSpeedway and the Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Natural Heritage.

Couchville Cedar Glade State Natural Area. This 122-acre site supports one of the largest populations [4]. It was designated as a natural area in 1995, expanded to protect more coneflower sites in 2001 and is jointly managed by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Natural Heritage and the Long Hunter State Park.

Mount View Road Cedar Glade. This site was purchased by The Nature Conservancy in 1989 and transferred to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation in 2005 [7, 8].

Vesta Cedar Glade Natural Area. This 150-acres site was designated as a natural area in 1986 [10]. It is jointly managed by the Tennessee Division of Forestry and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Natural Heritage.

Allvan Glade. It is unclear how many subpopulations are in this population and which land parcels they occur on. One natural subpopulation exists on U.S. Army Corps of Engineers land at J. Percy Priest Reservoir [2]. Another subpopulation was destroyed in 2005. The 185-acre Elsie Quarterman Cedar Glade Natural Area is on Army Corps land and supports a coneflower subpopulation which was introduced from an unprotected parcel of private land in 1989 [6]. It was designated as a natural area in 1998 and is co-managed by the Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency (as a Wildlife Management Area), the Army Corps, and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. The 230-acre Fate Sanders Barrens Natural Area was established in 1999 on Army Corps land and supports a subpopulation that was introduced from unprotected private lands [15].

Stone's River Cedar Glade and Barren Natural Area. This 185-acre site within the Stone's River National Battlefield was designated as a natural area in 2003 [5]. It supports two subpopulations totaling more than 2,500 plants [5]. There are apparently two additional subpopulations on the national battlefield [1]. Two of the subpopulations were planted in the early 1970s and two are of unknown origin. The natural area is jointly managed by the Stone’s River National Battlefield and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

Cultivated sites include the Warner Park Nature Center [12] and the 160-acre Cheekwood Botanic Garden, Owl's Hill Nature Center [11]. Coneflowers were planted on the latter in 1960s and are still present. Tennessee coneflower seeds are also sold to home gardeners by licensed horticulturists [12] and are being grown on an experimental rooftop garden designed to replicate a cedar glade [14].

CITATIONS

[1] Walck, J.L., T.E. Hemmerly, and S.N. Hidayati. 2002. The Endangered Tennessee Purple Coneflower, Echinacea tennesseensis (Asteraceae): Its Ecology and Conservation. Native Plants Journal 3: 54-64

[2] Lincicome, D. 2006. Personal communication with David Lincicome, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Division of Natural Heritage, Nashville, TN, January 13, 2006.

[3] TDEC. Gattinger's Cedar Glade and Barrens Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.tennessee.gov/environment//nh/natareas/gattinger/gattinger2.pdf

[4] TDEC. Couchville Cedar Glade State Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: http://www.tennessee.gov/environment//nh/natareas/couchville/couchville2.pdf

[5] TDEC. Stone's River Cedar Glade and Barren Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.tennessee.gov/environment//nh/natareas/stonesriver/stonesriver2.pdf

[6] TDEC. Elsie Quarterman Cedar Glade Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.state.tn.us/environment/nh/natareas/elsie/

[7] TNC. Mount View Road Cedar Glade. The Nature Conservancy website available at: http://nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/tennessee/preserves/art10125.html

[8] TNC. 2005. Four Preserves Being Transferred to State. Field Notes 2(1):2, The Nature Conservancy-Tennessee Chapter. Available at http://nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/tennessee/files/field_notes.pdf

[9] TDEC. Vine Cedar Glade Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.state.tn.us/environment/nh/natareas/vine/

[10] TDEC. Vesta Cedar Glade Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.tennessee.gov/environment/nh/natareas/vesta/

[11] Owl's Hill Nature Center. Checkwood Botanical Garden, www.cheekwood.org/nature/hike/wildflowers/cone.html

[12] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book), Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA.

[13] McKeown, K.A. 1999. A review of the taxonomy of the genus Echinacea. p. 482–489. In: J. Janick (ed.), Perspectives on new crops and new uses. ASHS Press, Alexandria, VA.

[14] Greenroofs.com. Greenroof Projects Database: Neuhoff Packing Plant Redevelopment. www.greenroofs.com/projects/pview.php?id=15

[15] TDE. 2006. Fate Sanders Barrens Natural Area, Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation website: www.state.tn.us/environment/nh/natareas/fatesanders/

[16] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Removal of Echinacea tennesseensis (Tennessee Purple Coneflower) From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants. August 3, 2011. 76 FR 46632.

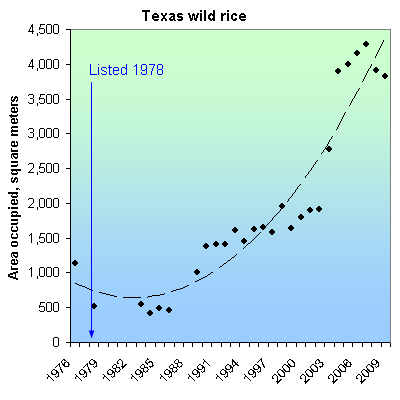

Texas wild rice (Zizania texana)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/14/1980 | Listed: 4/26/1978 | Recovery plan: 2/14/1996 |

Range: TX(b) ---

SUMMARY

Texas wild rice populations declined due to lowered water levels in the San Marco River, river dredging and damming, and riverside construction. In recent years, recreational impacts have become a concern. From a low point of only 454 square meters being occupied, the Texas wild rice benefitted by conservation actions such that 4,161 square meters were occupied by 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

Texas wild-rice (Zizania texana), an aquatic perennial grass found in the San Marcos River (including Spring Lake and its irrigation waterways) near the city of San Marcos, Texas, was abundant when the species was first described in 1933 [1]. By 1967, populations had declined drastically with reports of only one plant in Spring Lake, one in the uppermost part of the San Marcos River, and only scattered plants in the lower 2.4 kilometers of the river [1]. These declines were tied to increased pumping and diversion of Edwards Aquifer groundwater that lowered water levels in the San Marcos River and exposed shallows where Texas wild rice typically grew [2]. In addition, river dredging and damming, riverside construction, and bottomland cultivation destroyed plants, altered stream flows and temperature, and increased siltation [2]. Past seed harvesting had also inhibited successful reproduction [2].

In 1976, a survey estimated 1,131 square meters of Texas wild-rice in the San Marcos River, primarily concentrated in the extreme upper and lower segments of the area known as the upper San Marcos River; no plants were found in Spring Lake [1]. Declining numbers of plants, combined with a lack of sexual reproduction (existing plants appeared to be reproducing only vegetatively) led to the listing of Texas wild rice as endangered in 1978 [3]. Critical habitat was designated in 1980 [1]. A 1986 survey found that coverage had continued to drop to 454 square meters [1]. This decline is thought to have been caused by floating debris from Spring Lake (vegetation in the lake was periodically mowed for aesthetic purposes and the debris then allowed to float downstream ), streambed plowing in the city park area, plant collecting, and pollution of the stream [4]. By 1989, conditions had improved and coverage had increased to an estimated 1,005 square meters [1]. By 1994, coverage was up to 1,592 square meters and the plant’s distribution extended from the uppermost San Marcos River just below Spring Lake dam (an area where earlier surveys had not found plants) down to an area slightly below the wastewater treatment plant [1]. In recent years there has been an increase in Texas wild-rice coverage and it is now abundant in the upper portion of its range, although it is still rare farther downstream [5]. Populations are fragmented with large gaps between stands and with sporadic and spotty flowering that could lead to problems with pollination [3]. In one small area (Sewell Park) successful seed production was documented in 1998 and continued for several years [3]. By 2006, the area populated had risen to 4,161 square meters, although in-season fluctuations caused by low flow and recreation in Sewell Park were observed in 2006 and 2009 [7].

The first successful attempt at culturing Texas wild rice took place in 1975 when four clones removed from the river eventually produced 1,500 seeds that germinated and produced 500 plants [1]. In 1992 and 1993, an attempt was made to transplant cultured wild-rice plants into Spring Lake; 183 were planted near the dam and another 500 were planted on the northwest side of the lake [1]. Although at first, there was a slight increase in plants at these sites, numbers later declined [1]. Due to lack of monitoring, population trends at these sites are unknown and it is unclear whether this project was successful [1]. Since1996, fish hatcheries have played a critical role in the conservation of Texas wild rice [6]. About 40 plants are normally kept at the San Marcos hatchery and another 40 are maintained at Uvalde National Fish Hatchery in Uvalde, Texas [6]. In 2000, a breached dam caused the river to drop and narrow, leaving 25 percent of the Texas wild rice population either dry or in water flowing too fast [6]. In response, 184 rice plants were transferred to the San Marcos hatchery and another 60 were moved to safer areas within the river [6]. Another recent threat to the species is the invasion of a new exotic plant, water trumpet (Cryptocoryne beckettii). This native of southeast Asia is believed to have been introduced into the San Marcos River in 1993 and, although efforts have been made to remove it, its growth continues to outpace the removal effort [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. San Marcos and Comal Springs and Associated Aquatic Ecosystems Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, New Mexico. pp. x + 93 with 28 pages of appendices.

[2] Eckhardt, G. The Edwards Aquifer Website. <http://www.edwardsaquifer.net/species.html#Texas%20Wild%20Rice%20(Zizania%20texana)> accessed Arpil, 2006.

[3] Power, P. and F.M Oxely. 2004. Assessment of Factors Influencing Texas Wild Rice (Zizania Texana) Sexual and Asexual Reproduction. 2004 Final Report prepared for the Edwards Aquifer Authority, San Antonio, Texas.

[4] Beaty, H.E. 2001. Texas Wild Rice. In Handbook of Texas Online. Available at <http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/TT/ttt1.html> accessed April, 2006.

[5] Edwards Aquifer Authority. 2004. Draft Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Amended 9/21/04

[6] Springer, C. 2000. Texas Wild-rice Finds Refuge at Hatchery. Endangered Species Bulletin. XXV(3):34.

[7] Edwards Aquifer Area Expert Science Subcommittee. 2009. Analysis of Species Requirements in Relation to Spring Discharge Rates and Associated Withdrawal Reductions and Stages for Critical Period Management of the Edwards Aquifer. Available online at http://edwardsrip.org/pdfs/sciencesc2009.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2011.

Virginia round-leaf birch (Betula uber)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/26/1978 | Recovery plan: 9/24/1990 |

Range: VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

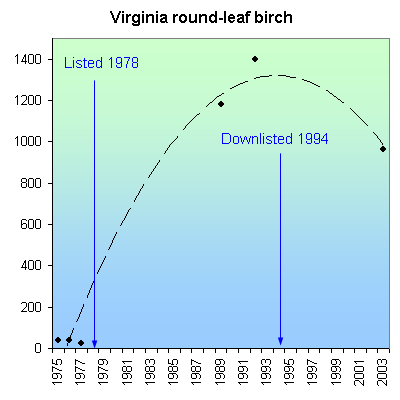

The Virginia round-leaf birch occurs only in Virginia's Cressy Creek watershed, where it was nearly driven to extinction by habitat degradation from logging and agriculture. Previously thought extinct, 41 trees were rediscovered in 1975, but declined to 39 then 26 over next two years. It was listed as an endangered species in 1978. By 2003, breeding, reintroduction and protection produced 961 wild trees in 20 populations.

RECOVERY TREND

Virginia round leaf birch (Betula uber), a moderate-sized tree with aromatic bark and a compact crown, was discovered in a single creek drainage in 1918 [1]. It was later thought extinct until the rediscovery of 41 trees along the banks of Cressy Creek in 1975 [1].

All 41 trees occurred within a 100-meter-wide band of highly disturbed second-growth forest along a one-kilometer stretch of the Cressy Creek floodplain [1]. Both public and private land was included in this strip and the population was entirely surrounded by agricultural land [1]. Extensive searches of the surrounding area did not uncover additional populations and by 1977, the one known population had declined to 26 trees, prompting the creation of the “Betula Uber Protection, Management and Research Coordinating Committee” [2]. Through their efforts, in 1978 the Virginia round leaf birch became the first tree species to gain protection under the Endangered Species Act [2].

In 1981, two areas were cleared of vegetation near potential seed sources in an effort to enhance natural regeneration [1]. Eighty-one round-leaf birch seedlings were found in one cleared area; however, all of the seedlings that remained at the end of the second growing season were gone (probably a result of vandalism) by 1986 [1].

Seeds were also gathered, germinated under greenhouse conditions, and held in cultivation for two to three growing seasons [1]. Starting in 1984 these seedlings were transplanted to 20 clearings that had been created in wooded areas of the Cressy Creek Watershed [1]. Five populations per year were established over a four-year period [1]. Each newly established population consisted of 96 individuals [1]. Measures such as fencing trees from browsers and removing competing vegetation were taken to promote the establishment of these populations [1]. The U.S. National Arboretum also produced 50 plants that were distributed to arboreta, botanical gardens and nurseries [1].

Although the single wild-seeded population of Virginia round leaf birch has continued to decline [2], as of 1994, 19 of the 20 introduced populations were thought to be self sufficient and totaled 1,400 trees, most of which occur on the Jefferson National Forest. This led to the 1994 rule to downlist the round leaf birch to threatened [1].

As of 2003, eight of the original 41 trees remained, along with an additional 953 cultivated trees for a total of 961 [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Reclassification of the Virginia Round-Leaf Birch (Betula Uber) From Endangered to Threatened. Federal Register, 59 FR 59173.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Virginia round leaf birch (Betula Uber). Northeast Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hadley, MA. Accessed at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pdf/vabirch.pdf on 11/23/05.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Virginia Round-Leaf Birch Betula uber (Ashe) Fernald 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Gloucester, VA. 26 pp.