Aleutian Canada goose (Branta hutchinsii leucopareia)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/30/1991 |

Range: AK(b), CA(s), OR(s), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

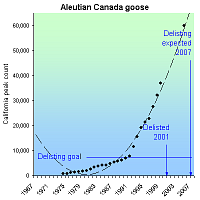

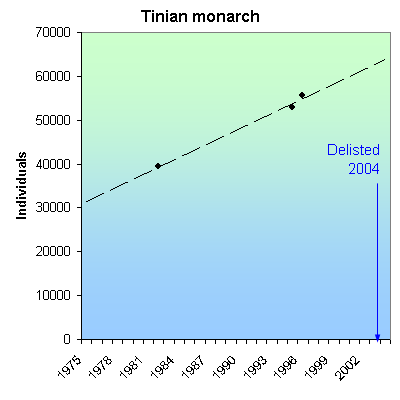

In the 1960s the Aleutian Canada goose was feared extinct due to predation by non-native foxes introduced to its nesting island, and to a less degree, by excessive hunting and loss of winter and migration habitat. It was rediscovered in 1962. In 1967 it was listed as an endangered species and grew from ~790 birds in 1975 to ~60,000 in 2005. It was declared recovered and removed from the endangered list in 2001, seven years earlier than projected by its recovery plan.

RECOVERY TREND

The Aleutian Canada goose was an abundant subspecies of Canada goose that nested in the northern Kuril and Commander Islands, in the Aleutian Archipelago, and on islands south of the Alaska Peninsula east to near Kodiak Island [1]. The birds wintered in Japan and in the coastal western United States to Mexico [1].

The fur industry began introducing Arctic and red foxes to the goose's nesting islands 1750, reaching a peak between 1915 and 1939 [2]. Foxes were released on 190 islands within the Aleutian Canada goose’s breeding range in Alaska [1]. They decimated the species by predating heavily on eggs, goslings and flightless molting geese.

Hunting, especially on the migration and wintering range in California, also contributed to population declines, as did loss and degradation of migration and wintering habitat [1]. Between 1938 and 1962, there were no sightings of Aleutian Canada geese, and it was feared the subspecies had gone extinct [1]. In 1962, however, a remnant population was discovered on rugged, remote Buldir Island in the western Aleutians [2].

After the Aleutian Canada goose was listed as endangered, efforts to eliminate introduced foxes from former nesting islands and to reintroduce the geese were initiated [1]. Hunting closures were implemented in wintering and migration areas [3]. Also, in the early 1980s biologists discovered two additional islands that supported small numbers of breeding Aleutian Canada geese [1].

Although early releases of captive-reared geese proved largely unsuccessful due to low survival rates, populations began to increase, likely due to the hunting closures in California and Oregon [1]. Translocations of wild-caught geese, implemented when the population on Buldir Island became large enough, proved more successful and as new breeding colonies became established, numbers increased rapidly [1]. In addition, important wintering and migration habitat in California and Oregon was acquired and designated as national wildlife refuges, and local landowners were encouraged to protect and manage habitat [2].

By 1990, the population had increased to an estimated 6,300, up from 790 counted in 1975, and the species was downlisted from endangered to threatened [1]. Between 1990 and 1998, the average annual population growth rate was estimated at 20 percent, and new populations became firmly established on Agattu, Alaid and Nizki islands in the western Aleutians [2]. In 1999, the population reached more than 30,000 [3]. In 2001, with the population estimated at 37,000, the Fish and Wildlife Service declared the Aleutian Canada goose recovered, and the species was taken off the list of endangered species [1]. In 2005 the population was approximately 60,000 [4]. While the Aleutian Canada goose continues to rebound in the western Aleutians, Russian scientists are conducting an ongoing program to reestablish it in the Asian portion of the birds’ range [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Rule to Remove the Aleutian Canada Goose From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register (66 FR 15643).

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. An Endangered Species Success Story: Secretary Norton Announces Delisting of Aleutian Canada Goose. News Release, March 19, 2001. Available at <http://news.fws.gov/newsreleases/R9/571EA0D1-2270-400B-B350418F893BCCEC.html?CFID=1629288&CFTOKEN=63346966>

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Aleutian Canada Goose Road to Recovery Timeline. Available at <http://alaska.fws.gov/media/pdf/road-to-recovery.pdf>.

[4] Trost, R. E., and M. S. Drut. 2005. 2005 Pacific Flyway data book: waterfowl harvests and status, hunter participation and success, and certain hunting regulations in the Pacific Flyway and United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Portland, Oregon.

American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 8/11/1977 |

| Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(b), AR(m), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(m), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(m), KY(b), LA(m), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(m), MO(m), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(m), OH(b), OK(m), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(m), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

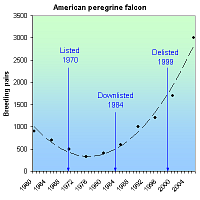

The use of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides thinned American peregrine falcon eggshells, causing reproductive failure and population declines. The banning of DDT, captive-breeding efforts and nest protections allowed falcons to increase from 324 breeding pairs in 1975 to 3,005 pairs as of 2006. The species was delisted in 1999.

RECOVERY TREND

The American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) breeds only in North and Central America and occurs throughout much of North America from the subarctic boreal forests of Alaska and Canada south to Mexico [1]. It is estimated that prior to the 1940s, there were approximately 3,875 nesting pairs of peregrines in North America [1]. From the 1940s through the 1960s, however, the population of the peregrine, and many other raptors, crashed as a result of the introduction of synthetic organochlorine pesticides to the environment. By 1975, there were only 324 known nesting pairs of American peregrine falcons in the U.S. [2].

Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [1]. Organochlorine pesticides were put into use following World War II. Use peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s and continued through the early 1970s [1]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey because they ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches [1]. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. During the period of DDT use in North America, eggshell thinning and nesting failures were widespread in peregrine falcons, and in some areas, successful reproduction virtually ceased [1].

The degree of exposure to these pesticides varied among regions, and peregrine falcon numbers in more contaminated areas suffered greater declines [1]. The eastern population plunged from an estimated 350 active nest sites in the 1930s and 1940s to no active breeding birds from 1964 to 1975 [3]. Peregrine falcons in the Great Plains states east of the Rocky Mountains and south of U.S. and Canadian boreal forests were also essentially extirpated [1]. West of the 100th meridian, peregrine falcons were significantly reduced [1]. Local populations were greatly depressed or extirpated and by 1965 fewer than 20 pairs were known west of the U.S. Great Plains [1].

In 1970, the American peregrine was listed as endangered and efforts to recover the species began. The use of DDT was banned in Canada in 1970 and in the United States in 1972 [1]. This was the single-most significant action in the recovery of the peregrine falcon [1]. In addition, in the eastern United States, efforts were made to reestablish peregrine falcons by releasing offspring from a variety of wild stocks that were held in captivity by falconers [1]. The first experimental releases of captive-produced young occurred in 1974 and 1975 in the eastern United States [1]. These and future releases demonstrated that “hacking,” the practice of retaining and feeding young captive bred birds in partial captivity until they are able to fend for themselves, was an effective method of introducing captive-bred peregrines to the wild [1]. Since then, more than 6,000 falcons have been released in North America [1]. Approximately 3,400 peregrines were released in parts of southwest Canada, the northern Rocky Mountain States, and the Pacific Coast states [1].

In the late 1970s, Alaska became the first place American peregrine falcon population growth was documented and, by 1980, populations began to grow in other areas [1]. Not only did the number of peregrine falcons begin to increase, productivity (another important measure of population health) improved [1]. Efforts to reestablish peregrine falcons in the East and Midwest proved largely successful, leading to downlisting of the species in 1984 [1], and by 1999 peregrines were found to be nesting in all states within their historical range east of the 100th meridian, except for Rhode Island, West Virginia and Arkansas [1]. In highly urban areas, peregrine falcons showed great adaptability, and began substituting skyscrapers for natural cliff faces as nesting sites [4]. By 1998, the total known breeding population of peregrine falcons was 1,650 pairs in the United States and Canada, far exceeding the recovery goal of 456 pairs. Other recovery goals, including estimates of productivity, egg-shell thickness, and contaminants levels, had also been met, allowing the species to be delisted in 1999 [1]. Monitoring of American peregrine populations has continued under a post-delisitng monitoring plan [5]. The estimated North American population was 3,005 pairs as of 2006 [6].

ALASKA: Surveys conducted between 1966 and 1998 along the upper Yukon River demonstrated increases in the number of occupied nesting territories from a low of 11 known pairs in 1973 to 46 pairs in 1998 [1]. Similarly, along the upper Tanana River, the number of occupied nesting territories increased from two in 1975 to 33 in 1998 [1]. The recovery objective of 28 occupied nesting territories in the two study areas was first achieved in 1988, with 23 nesting territories on the Yukon River and 12 on the Tanana River [1].

PACIFIC STATES: By 1976, no American peregrine falcons were found at 14 historical nest sites in Washington [1]. Oregon had also lost most of its peregrine falcons and only one or two pairs remained on the California coast [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 to 1998 indicated a steadily increasing number of American peregrine falcon pairs breeding in Washington, Oregon and Nevada [1]. Known pairs in Washington increased from 17 to 45 and in Oregon from 23 to 51 [1]. The number of American peregrine falcons in California increased from an estimated low of five to 10 breeding pairs in the early 1970s to a minimum of 167 occupied sites in 1998 [1]. The increase in California was concurrent with the restriction of DDT and included the release of more than 750 American peregrine falcons through 1997 [1].

ROCKY MOUNTAINS/SOUTHWEST: The Rocky Mountain/Southwest population of the American peregrine falcon has made a profound comeback since the late 1970s when surveys showed no occupied nest sites in Idaho, Montana or Wyoming and only a few pairs in Colorado, New Mexico and the Colorado Plateau, including parts of southern Utah and Arizona [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 through 1998 indicated that the number of American peregrine falcon pairs in the Rocky Mountain/Southwest area has steadily increased [1]. In 1991, there were 367 known pairs; in 1998 the number of pairs increased to 535 [1].

EASTERN STATES: The eastern peregrine population has a unique history and complex status under the Act [1]. Peregrine falcons were extirpated in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada by the mid-1960s [1]. Releases of young captive bred peregrines have reestablished populations throughout much of their former range in the East [1]. In 1998, 193 pairs were counted in five designated eastern state recovery units [1]. The number of territorial pairs recorded in the eastern peregrine falcon recovery area increased an average of 10 percent annually between 1992 and 1998 [1]. Equally important, the productivity of these pairs during the same seven-year period averaged 1.5 young per pair, demonstrating sustained successful nesting [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Final Rule to Remove the American Peregrine Falcon from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, and to Remove the Similarity of Appearance Provision for Free-Flying Peregrines in the Conterminous United States. Federal Register (64 FR 46542).

[2] Hoffman, C. 1999. The Peregrine Falcon is Back! New release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 20, 1999.

[3] Clark, K. 2005. The Peregrine Falcon in New Jersey, Report for 2005. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program.

[4] New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. Fact sheet, Peregrine Falcon Falco pereginus. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program. Website <http://www.njfishandwildlife.com/tandespp.htm> accessed February, 2006.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Monitoring Plan for the American Peregrine Falcon, A Species Recovered Under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Endangered Species and Migratory Birds and State Programs. Pacific Region, Portland Oregon 53pp.

[6] Green, M., T. Swem, M. Morin, R. Mesta, M. Klee, K. Hollar, R. Hazelwood, P. Delphey, R. Currie, and M. Aramal. 2006. Monitoring Results for Breeding American Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus anatum), 2003. Biological Technical Publication BTP-R1005-2006. U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(m), AR(m), CA(m), CO(m), CT(m), DE(m), DC(m), FL(m), GA(m), ID(m), IL(m), IN(m), IA(m), KS(m), KY(m), LA(m), ME(m), MD(m), MA(m), MI(m), MN(m), MS(m), MO(m), MT(m), NE(m), NV(m), NH(m), NY(m), NM(m), NJ(m), NC(m), ND(m), OH(m), OK(m), OR(m), PA(m), RI(m), SC(m), SD(m), TN(m), TX(m), UT(m), VT(m), VA(m), WA(m), WV(m), WI(m), WY(m) ---

SUMMARY

The Arctic peregrine falcon declined due to the egg shell-thinning effects of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides. Its listing as an endangered species in 1970 (along with other birds of prey) prompted the EPA to ban DDT in 1972. Counts of migratory Arctic falcons increased from 103 in 1976, to 1,017 in 2004. The species was downlisted to threatened in 1984 and delisted in 1991.

RECOVERY TREND

The Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius) is one of three peregrine falcon subspecies [1]. It nests in tundra regions of Alaska, Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Quebec, and possibly Labrador), and the ice-free perimeter of Greenland [1]. It is a long-distance migrant that winters in Latin America from Cuba and Mexico south through Central and South America [1].

Severe declines in peregrine falcon numbers began in the 1950s [1]. These declines were linked to organochlorine pesticides that were put into use following World War II, and whose use peaked in the late 1950s-early 1960s [1]. Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [2]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey which, being at the top of the food chain, ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. Arctic peregrine numbers reached their lowest levels in the early 1970s and in some areas of North America successful reproduction virtually ceased [1]. Populations are thought to have decreased by as much as 80 percent [2].

The listing of the Arctic peregrine falcon as endangered in 1970--as well as the bald eagle, brown pelican, and American peregrine falcon shortly before--fostered a national outcry against the production and spaying of DDT. In 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency banned most used of DDT in the United States [1]. Canada had already restricted DDT use in 1970. These restrictions are the central cause of the recovery of the Arctic and American peregrine falcons (the bald eagle and brown pelican benefited greatly as well, but their recovery also involved substantial habitat protections and reintroductions).

As DDT levels declined after 1972, peregrine falcon productivity rates rose to pre-DDT levels and the population size and range began to increase. This happened most rapidly in northern areas, where pesticide exposur was lower and impacts upon populations were less severe [1]. In 1984, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service downlisted the Arctic peregrine falcon from endangered to threatened status [2, 6]. In 1991, the agency initiated a review determine if the species had recovered [2] and in 1994 removed it from the endangered species list [6].

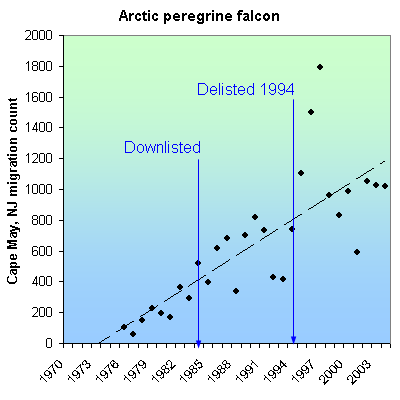

Four major factors were considered in the delisting process: (1) Population size and trend, (2) reproductive performance, (3) pesticide residues in eggs, and (4) eggshell thickness [1]. Despite a lack of long-term studies using consistent methodologies, there was strong evidence of significant population increases throughout the Arctic [1]. Four areas in northern North America (one in Alaska and three in Canada’s North West Territories) for which historical survey information was available indicated the number of Arctic peregrine pairs occupying nesting territories increased since the 1960s [1]. Some areas of Alaska even exceeded the original estimates of pre-DDT-era population size [1]. In addition, in the eastern Arctic, peregrines began nesting in previously vacant nesting sites [1]. Standardized yearly migration counts at New Jersey’s Cape May, an area where Arctic peregrines concentrate during migration, also saw increasing numbers, most likely from Arctic breeding grounds especially in Greenland and eastern Canada (these counts may have also contained peregrines in the American subspecies; however, banding recoveries indicate that the majority of peregrines along the East Coast during fall migration are from the Arctic and thus represent a true increase in Arctic peregrine numbers) [1].

Productivity in all regions where data had been gathered was sufficient to support a stable or increasing population since the 1980s [1]. There had also been improvements in levels of DDE concentration in eggs. Concentrations in excess of 15-20 parts per million (wet weight basis) are associated with high rates of nesting failure. Residue in eggs in 1993 was well below this critical level [1]. Alaskan eggshells collected between 1988 to 1991 were on average only 12 percent thinner than pre-DDT thickness (17 percent or greater reduction in thickness results in population declines).

Arctic peregrine falcon numbers have continued to rise after the species' delisting. On the Sagavanirktok River in Alaska, where Arctic peregrine surveys have been conducted since the late 1950s, the number of pairs increased from five in 1958, to 23 in 1992, to 25 in 1999 [3]. Migration counts at the Cape May Hawkwatch site in New Jersey increased from 103 in 1976 to 1,024 in 2003 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Proposal to Remove the Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 58 Fed. Reg 188.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Peregrine falcon, (Falco peregrinus anatum, Falco peregrinus tundrius, Falco peregrinus pealei). Species account. Website <http://www.fws.gov/species/species_accounts/bio_pere.html> accessed October, 2005.

[3] Wright, J.M. and P.J. Bente. 1999. Documentation of active peregrine falcon nest sites, 1 Oct 1994- 31 March 1998. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Annual research report. Endangered species conservation fund federal aid project SE-2-9, 10, and 11. Juneau, AK. 15 pp.

[4] Cape May Bird Observatory. 2012. Cape May Hawkwatch, Cape May, New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society. Website <http://www.njaudubon.org/Sightings/cmhw25.html> accessed April 2, 2012.

[5] NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Removal of Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 50796.

Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Atlantic DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/10/2001 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(b), DE(b), FL(s), GA(s), LA(s), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MS(s), NH(b), NY(b), NJ(b), NC(b), PR(s), RI(b), SC(b), TX(s), VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

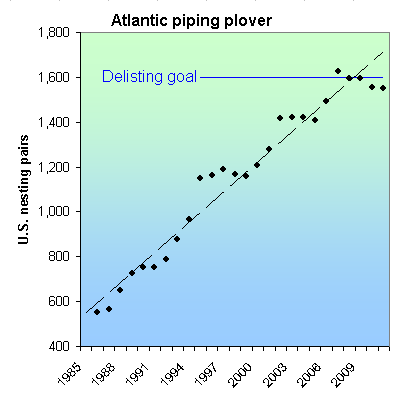

Atlantic piping plover populations initially declined due to hunting and the millinery trade. With these eliminated, it increased in the first half of the 20th century, but began declining after 1950 due to development, beach crowding and predation. It was listed as 1985 after which intensive habitat protection and control of recreationists and predators, increased its U.S. population from 550 pairs in 1986 to 1,550 in 2011, reaching its overall U.S. recovery goal in 3 of the last 5 years.

RECOVERY TREND

The Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus) breeds on Atlantic coastal beaches from Newfoundland to northernmost South Carolina [1]. Hunters and the millinery trade decimated the species in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were stopped by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The plover steadily recovered until about 1950, then began to decline again under pressure from development, beach stabilization programs, increased recreation, and anthropogenically caused increases in predation by native and introduced species.

Following its listing as an endangered species in 1985, the plover was subject to intense nest site, nest area, and predator management programs, resulting in the following population growth between 1986 and 2011 [1, 2, 3]:

POPULATION 1986-2011 GROWTH RECOVERY GOAL YEARS AT RECOVERY GOAL

Canada: 240 - 209 pairs 400 pairs 0

New England 184 - 825 pairs 625 pairs At least 100% of goal, last 14 years

New York/New Jersey: 208 - 431 pairs 575 pairs At least 90% of goal, 6 of last 9 years

South Atlantic: 158 - 294 pairs 400 pairs 0

U.S. population: 550 - 1,550 pairs 1,600 pairs At least 100% of goal, 3 of last 5 years

Total: 790 - 1,759 pairs 2,000 pairs At least 87% of goal, last six years

The 1996 federal recovery plan [1] established the following delisting criteria: 1) Increase and maintain for five years a total of 2,000 breeding pairs, distributed among four recovery units as follows: Canada, 400 pairs; New England, 625 pairs; New York-New Jersey, 575 pairs; Southern (DE-MD-VA-NC), 400 pairs. 2) Verify the adequacy of a 2,000-pair population of piping plovers to maintain heterozygosity and allelic diversity over the long term. 3) Achieve five-year average productivity of 1.5 fledged chicks per pair in each of the four recovery units described in criterion 1, based on data from sites that collectively support at least 90 percent of the recovery unit’s population. 4) Institute long-term agreements to assure protection and management sufficient to maintain the population targets and average productivity in each recovery unit. 5) Ensure long-term maintenance of wintering habitat, sufficient in quantity, quality and distribution to maintain survival rates for a 2,000-pair population.

- The New England unit exceeded its recovery plan goal of 625 nesting pairs each of the 14 years between 1998 and 2011 and cointinues to grow.

- The New York/New Jersey unit grew steadily from 1986 to 2007, the only year in which it reached its recovery plan goal. It declined in all years from 2008 to 2011. While it has been at at least 90% of its goal in six of the nine years ending in 2011, the recent declines are worrisome.

- The Southern recovery unit was relatively stable betwee 1986 and 2003, grew rapidly between 2004 and 2008, then remained relatively stable at a reduced level from 2009 to 2011. It has never reached its recovery goal and has always been the smallest and slowest growing of the three U.S. recovery units.

- The U.S. population as a whole had strong, steady growth between 1986 and 2007, increasinging from 550 to 1,624 pairs. 2007 was the first year it reached its recovery goal of 1,600 pairs. From 2009 to 2011, it declined slightly to 1,550 pairs. The U.S. trend is dominated by the New England recovery unit which is the largest, fastest and most consistently growing.

- The Canadian recovery unit has periods of growth and decline, but remained at 200-250 nesting pairs in almost all years between 1986 and 2011. It the smallest of all the recovery units and the only one not to have experienced net growth since 1986.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), Atlantic Coast Population, Revised Recovery Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts. 258 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Abundance and productivity estimates – 2010 update: Atlantic Coast piping plover population. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/pdf/Abundance&Productivity2010Update.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Preliminary 2011 Atlantic Coast Piping Plover Abundance and Productivity Estimates, March 20, 2012. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/preliminary2011%2020March2012%20for%20AC%20website.pdf

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 214 pp.

Bald eagle (continental U.S. DPS) (Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Continental U.S. DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(b), AZ(b), AR(b), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(b), FL(b), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(b), KY(b), LA(b), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(b), MO(b), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(b), OH(b), OK(b), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(b), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

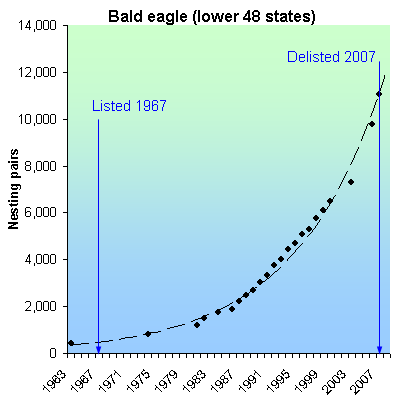

The bald eagle declined throughout the lower 48 states, and was extirpate from most of them due to habitat loss, persecution, and DDT-related eggshell thinning. The banning of DDT, increased wetland protection and restoration, and an aggressive, mostly state-based reintroduction program caused eagle pairs to soar from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when the eagle was removed from the endangered list.

RECOVERY TREND

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) first declined in the 1800s at the hands of trophy hunters, feather collectors, and wanton killing [1]. It was already extirpated or at low numbers in most states by the 1940s when DDT and other organochlorines became widely used. DDE, a breakdown product of DDT, accumulates in the fatty tissue of female eagles, impairing the formation of calcium needed for normal egg formation, causing a decline in reproductive success. DDT caused eagle numbers plummet further, and in 1967 the species was listed as endangered in the lower 48 states [1].

The eagle was joined on the list by the American peregrine falcon, Arctic peregrine falcon and brown pelican in 1970. The listing of these large, charismatic birds rallied the nation to band the production and sale of DDT in 1972.

Due to the DDT ban, increased habitat protection, and aggressive captive breeding and translocation programs (mostly run by state wildlife agencies), bald eagle pairs in the lower 48 soared from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when it was removed from the threatened species list [2, 7]. In 1984, 13 states lacked nesting eagles. By 1998, it was absent from only two. By 2006, it nested in all 48 states [7].

The eagle was proposed for delisting in 1998 [1] and again in 2006 [4]. It was downlisted in 1995 and delisted in 2007 [6].

The bald eagle is managed under five federal recovery plans, divided by region:

Chesapeake Recovery Region: Virginia east of Blue Ridge Mountains, Delaware, Maryland, the eastern half of Pennsylvania, West Virginia Panhandle and two-thirds of New Jersey. Delisting goals were met in 1996 [1]. As of 2003, there were more than 800 nesting pairs in this region [4].

Northern States Recovery Region: 25 Northernmost states. Delisting goals were met in 1991, with 1,349 occupied breeding areas across 20 states. As of 2007, there were an estimated 4,215 breeding pairs in the northern recovery region [6].

Pacific Recovery Region: Idaho, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Montana and Wyoming. Numeric delisting goals were met in 1995 [1]. As of 2001, there were

1,627 nesting pairs in this recovery region [4].

Southeastern Recovery Region: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and eastern Texas. Downlisting goals were met between 1991 and 1998. More than 1,700 pairs were counted in 2000 [4, 6].

Southwestern Recovery Region: Oklahoma and Texas west of the 100th meridian, New Mexico, Arizona and California bordering the Lower Colorado River. The goal established in the recovery plan has been exceeded. In 2003, 46 occupied breeding areas were reported in New Mexico and Arizona. In 2004, the Arizona had 41 occupied breeding areas [4].

In the eight Northeast states from New Jersey to Maine and Vermont, nesting eagle pairs increased from 21 in 1967 to 562 in 2005 [5]. The majority were in Maine, which supported all 21 pairs in 1967 and 385 pairs in 2005. Eagles returned to Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1990, with the former supporting 19 pairs in 2005 and the latter eight in 2004. In 2005 there were 53 pairs in New Jersey, 94 in New York and one in Vermont. The Northeast is also an important wintering area, with the Connecticut population increasing from 20 to 92 between 1979 and 2005, and the New York population increasing from six to 194 between 1978 and 2006 [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Proposed rule to remove the bald eagle in the Lower 48 states from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register, July 6, 1999 (64 FR 36453)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Bald Eagle Numbers Soaring. May 14, 2007 press release.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Removing the bald eagle in the Lower 48 States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife; reopening of public comment period with new information. Federal Regiter, February 16, 2006 (71 FR 8238).

[5] Center for Biological Diversity. 2006. Bald eagle trends in the Northeastern United States. Tucson, AZ.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Removing the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Final Rule. 72 Fed. Reg 37346.

[7] Suckling, K. and W. Hodges. Status of the bald eagle in the lower 48 states and the District of Columbia: 1963-2007. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ. Available at http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/bald_eagle/report/index.html.

Brown pelican (Eastern DPS) (Pelecanus occidentalis (Atlantic/Eastern Gulf Coast DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1980 |

Range: AL(b), CT(o), DE(s), FL(b), GA(b), ME(o), MD(b), MA(o), NH(o), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), RI(o), SC(b), VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

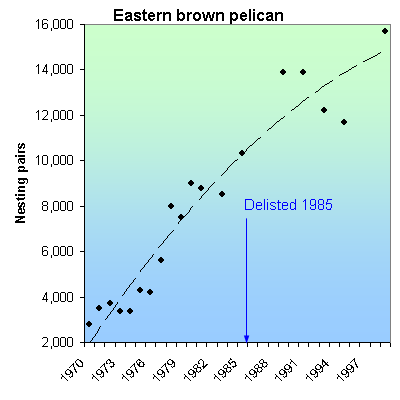

Reproductive failure due to eggshell thinning, caused by the pesticide DDT, was the main cause of brown pelican population declines. The pelican has recovered, but now faces threats from offshore oil and wind development, rising sea levels and hurricanes. Brown pelican nests on the Atlantic Coast increased from 2,796 in 1970 to 15,670 in 1999; on the eastern Gulf Coast, nest numbers increased slightly from 5,100 in 1970 to 5,682 in 1999. The eastern brown pelican was delisted in 1985 due to recovery.

RECOVERY TREND

The southeastern brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis pop.) breeds from Maryland south along the Atlantic Coast to southern Florida and westward along the Gulf Coast to Alabama [1]. The brown pelican occurs regularly as a non-breeder in New York, New Jersey and Delaware, and occasionally northward to Nova Scotia.

The listing history of this population is complex. The brown pelican species was listed as endangered throughout its range in 1970. The "southeastern brown pelican," a taxon not previously recognized by scientists or wildlife managers, was separated from the rest of the species, declared recovered, and delisted in 1985 [1]. This distinct population includes, and is limited to, all portions of the eastern brown pelican (P. o. carolinensis) east of Mississippi.

Nests on the Atlantic Coast increased from 2,796 in 1970 to 10,300 in 1985, when it was delisted, and numbered 15,670 in 1999. Nests on the Gulf Coast (eastern and western) increased from 5,100 in 1970 to 7,000 in 1985 when the Eastern Gulf Coast population was delisted, then continued increasing to 24,400 in 1999.

MARYLAND: Prior to 1987, when six pairs nested on a state-owned dredge spoil island in Chincoteague Bay near Assateague Island, the brown pelican had not been recorded nesting in Maryland [3,4]. Nesting pairs increased from 26 in 1989 to 1,042 in 2008 [5].

VIRGINIA: The brown pelican was not recorded as nesting in Virginia prior to 1987 [4]. Nests increased from 37 in 1989 to 1,406 in 1999 [2]. In 2008 there were 1,924 breeding pairs in the state [6].

NORTH CAROLINA: Nests increased from 75 in 1976 [1] to 4,350 in 1999 [2]. In 2007 there was a marked decrease to 3,452 nests [7].

SOUTH CAROLINA: Nests increased from 1,117 in 1970 [1] to 7,739 in 1989, then decreased to 3,486 in 1999 [2]. The latter decline is believed to be the result of key island habitats eroding away. The birds likely moved to other states. In 2009 there were 3,985 nests [8].

GEORGIA: The first record of nesting pelicans was in 1988 [2]. Nests increased from 200 in 1989 to around 3,500 nests in 2007 [2,9].

FLORIDA: Nests increased from 7,690 in 1970 [1] to 12,312 in 1989 [2], then decreased to only 4,724 nesting pairs in 2007 [10], which is the lowest number of nests recorded in the state since before 1970.

ALABAMA: The brown pelican was not recorded to nest in Alabama prior to 1983 [1]. Nests increased from 588 in 1989 to around 5,000 as of 2006 [11].

NEW JERSEY: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer. Several pairs unsuccessfully attempted to nest in 1992 and 1994 [2].

NEW YORK: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer, but have not been recorded nesting [2].

DELAWARE: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer, but have not been recorded nesting [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Removal of the brown pelican in the southeastern United States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register (50:4938).

[2] Shields, M. 2002. Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 609 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[3] USGS. 2005. Biological and ecotoxicological characteristics of terrestrial vertebrate species residing in estuaries. U.S. Geological Survey. Website (www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bioeco/bpelican.htm) accessed December 30, 2005.

[4] Brinker, D.F. 2006. Brown pelican nesting in Maryland, 1986-2005. Data provided by David Brinker, Natural Heritage Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Cantonsville, MD, January 3, 2006.

[5] Maryland Department of Natural Resources. 2008. Creature Feature: Brown Pelican. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mydnr/creaturefeature/brownpelican.asp

[6] Watts, B. D. and B. J. Paxton. 2009. Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in

coastal Virginia: 2009 breeding season. CCBTR-09-03. Center for Conservation Biology, College of William and Mary/Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA 21 pp.

[7] North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. 2008. Annual Program Report 2007-2008. Wildlife Diversity Program Division of Wildlife Management. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://www.ncwildlife.org/Wildlife_Species_Con/documents/AnnualProgramReportWDinWM07-08.pdf

[8] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR). 2010. Untitled population data provided to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Obtained via FOIA FWS-2010-00941.

[9] Jodice, P.G.R., T.M. Murphy, F.J. Sanders, and L.M. Ferguson. 2007. Longterm Trends in Nest Counts of Colonial Seabirds in South Carolina, USA.

[10] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2007. Fiscal Year 2006-2007 Progress Report on activities of the Endangered and Threatened Species Management and Conservation Plan. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://www.myfwc.com/docs/WildlifeHabitats/Endangered_Threatened_Species_Progress_Report_2006_2007.pdf#search=%22brown%20pelican%2

[11] Morley, D.F. 2006. 2006 Alabama Coastal BirdFest. Conservation News, Alabama Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources. Accessed August 2, 2010 at: http://www.outdooralabama.com/outdoor-alabama/07-06news.pdf.

California brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus )

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 2/3/1983 |

Range: AZ(o), CA(b), OR(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

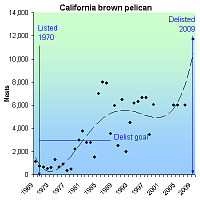

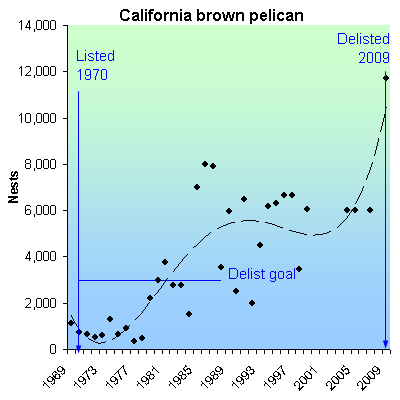

The California brown pelican declined due to habitat loss, reproductive failure from DDT-related eggshell thinning and toxic exposure to the pesticide endrin. It was listed as endangered in 1970, but continued declining to a low of 466 pairs in 1978. Since then, it as increased, though inconsistently, reaching 11,695 nesting pairs when delisted in 2009. The banning of DDT and protection of nesting areas, especially in Channel Islands National Park, are responsible for its recovery.

RECOVERY TREND

The California brown pelican’s (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) breeding range extends from California's Channel Islands south along the Pacific coast to Baja California, eastward throughout most of the Gulf of California, and southward along the mainland Pacific coast of Mexico to Islas Tres Maria [1]. It formerly bred as far north as Point Lobos in Monterey County. Currently, U.S. nesting colonies are located on West Anacapa and Santa Barbara islands of the California Channel Islands. The nesting range recently expanded to the Salton Sea [1]. As non-breeders, pelicans occur from southern British Columbia to El Salvador and inland in the U.S. to Southern California and Arizona.

The California nesting population declined from 1,125 to 727 annual nests between 1969 and 1970 when the species was placed on the list of endangered species [1]. The primary cause of decline was exposure to the pesticides endrin, which caused pelican mortality, and DDT, which caused egg-shell thinning. The Channel Island population was particularly impacted by a single Los Angeles factory which began discharging 200 to 500 kilograms of DDT daily in 1952.

DDT was banned in 1972, in large part because of the endangered species listing of the pelican, bald eagle and peregrine falcon. Following the ban, the pelican’s reproductive success began to improve quickly, although breeding effort did not show significant improvement until the early 1980s [3]. With the exception of a good year in 1974, the number of nests remained at low levels through 1978 when a low of 466 nests was recorded. Between 1979 and 1987, the population rose rapidly to 7,900 nests. Between 1987 and 2004, the number of nests fluctuated around a mean of about 5,000 nests. The 2004 nest count was about 7,500 (6,000 on West Anacapa and 1,500 on Santa Barbara Island). The 2006 nest count was about 9,000 with nesting on all three Anacapa islands (4,000 to 5,000), Santa Barbara Island (4,000) and Prince Island (43) [5]. 2006 was the first year since monitoring began that breeding occurred on all three Anacapa islands and the first time since 1939 that breeding occurred on Prince Island. In 1996, a small population of pelicans began nesting in the Salton Sea and has been present in most years since.

The California brown pelican was delisted in 2009 due to recovery, at which time there were 11,695 nesting pairs [7].

CITATIONS

[1] Shields, M. 2002. Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 609 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[2] Rogers, T. 2004. Spate of juvenile deaths follows breeding success. San Diego Union Tribune, August 1, 2004.

[3] Harrison, S.C. 2005. Petition to Delist the California Brown Pelican From the Listed of Endangered or Threatened Species Under the Endangered Species Act. Hunton & Williams, Washington, D.C., December 14, 2005.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. 90-Day Finding on a Petition to Delist the California Brown Pelican and Initiation of a 5-Year Review for the Brown Pelican. Federal Register, May 24, 2006 (71 FR 29908-29910).

[5] Broddrick, L.R. 2006. October 6, 2006 memorandum from L. Ryan Broddrick, Director, California Department of Fish and Game to John Carlson, Jr., Executive Director, California Fish and Game Commission, "Subject: Request of Endangered Species Recovery Council to delist the California brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) under the California Endangered Species Act."

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. 5-Year Review of the Listed Distinct Population Segment of the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). Albuquerque, NM.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Removal of the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, November 17, 2009 (74 FR 59444-59472).

California condor (Gymnogyps californianus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/24/1976 | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 4/25/1996 |

Range: AZ(b), CA(b) --- NV(x), OR(x), UT(x), WA(x)

SUMMARY

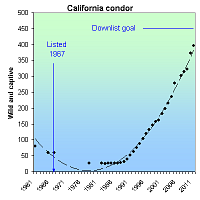

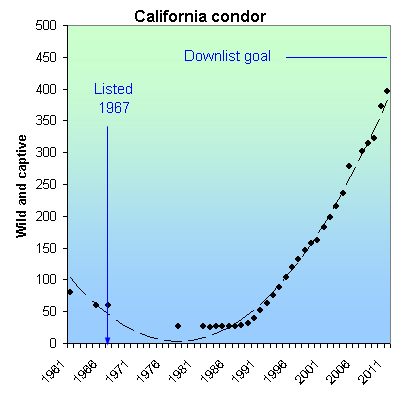

The California condor was nearly driven extinct by DDT, lead poisoning from ingested bullet fragments, and hunting. Lead poisoning remains a major threat to the species. Wild condors declined to nine birds by 1985. A captive-breeding and release program has increased the population to 386 birds as of 2012, including 213 wild and 173 captive birds.

RECOVERY TREND

The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) is a member of the vulture family and one of the largest flying birds in the world [1]. Ten-thousand years ago, its range extended across most of North America, but by the arrival of Europeans, its range was largely restricted to the Pacific Coast from British Columbia south to Baja California. By 1940, it was found only in the coastal mountains of Southern California where it nested in the rugged mountains and scavenged in the foothills and grasslands of the San Joaquin Valley. It was listed as an endangered species in 1967 and was given critical habitat the same year.

The condor's decline was driven by DDT which compromised reproduction, poisoning fromlead poisoning, shooting, collection, and drowning in uncovered oil sumps [1].

About 600 birds remained in 1890 [1, 2, 3]. It declined to about 60 birds in the late 1930s and early 1940s, 40 in the early 1960s, 27 in 1978, and nine in 1985. All remaining wild birds were taken into captivity in 1987. Since then, a successful captive breeding and reintroduction program increased the 2005 wild population to 121 and the captive population to 158 [2, 3].

The California Department of Fish and Game reports 302 condors in 2007; 315 in 2008; 322 in 2009; 373 in 2010; and 396 in 2011 [4].

The California condor now occurs in three wild populations: in mountains north of the Los Angeles basin, in the Big Sur area of the central California coast, and near the Grand Canyon in Arizona [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. California Condor Recovery Plan, Third Revision. Portland, Oregon. 62 pp.

[2] California Department of Fish and Game. 2005. California condor population size and distribution. Available at: http://www.dfg.ca.gov/hcpb/species/t_e_spp/tebird/Condor%20Pop%20Stat.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Condor population history. Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Available at: http://www.fws.gov/hoppermountain/cacondor/Pophistory.html.

[4] Ventana Wildlife Society. 2012. California Condor Recovery Program, Population Size and Distribution updates. Available at: http://www.ventanaws.org/pdf/Status_Reports/2012/Status_Report_February_2012.pdf.

California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/2001 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

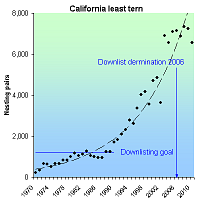

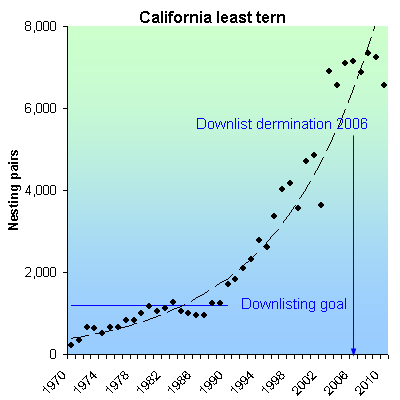

California least tern populations crashed in the late 19th century due to collection by the millinery trade. 20th century declines were driven by development, recreational crowding at beaches, and anthropogenically-exacerbated predation by wildlife. By 1970 when the tern was listed as endangered, just 225 pairs remained. Intensive habitat protection, predator control, and recreation management increased the tern to its overall delisting goal of 1,200 pairs in 1988 and to 6,568 pairs in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The California least tern (Sterna antillarum browni) nests in colonies on the Pacific coast of California and Baja, Mexico on relatively open beaches where vegetation is limited by tidal scouring [1]. It was formerly found in great abundance from Moss Landing, Monterey County, Calif. to San Jose del Cabo, southern Baja California, Mexico. It declined in the 19th and early 20th centuries due to the millinery trade that hunted birds for their feathers for women's hats, but to a lesser degree than many East Coast birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1916 ended the threat, but the least tern plummeted again some decades later due to growing development and recreational pressures that destroyed habitat, disturbed birds, and increased predation by introduced and native species. The construction of the Pacific Coast Highway brought all these threats to much of California's coast. By the 1940s, terns were extirpated from most beaches of Orange and Los Angeles counties and were considered sparse elsewhere. To avoid humans, some tern colonies nest at inland mudflat and dredge fill sites, which appears to make them more susceptible to predation by foxes, raccoons, cats and dogs.

When placed on the endangered species list in 1970, just 225 nesting tern pairs were recorded in California [2]. Protection of nest beaches from development and disturbance, and active predator control programs allowed the species to steadily increase to about 7,100 pairs in California in 2004 [2, 5]. A portion of the increase in the 1970s is attributable to expansion and greater consistency in survey effort, but the greatest increases occurred from 1980 to the present. In 2004, 57 percent of nesting pairs occurred in San Diego County, 26 percent in Los Angeles and Orange counties, 10 percent in Ventura County, 1 percent in San Louis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties, and 6 percent in the San Francisco Bay [3]; the largest sites were at Camp Pendleton (21 percent), U.S. Navy lands at San Diego Bay (16 percent), Los Angeles Harbor, Pier 400 (15 percent), Point Mugu (8 percent), Alameda Point (6 percent), Batiquitos Lagoon Ecological Reserve (6 percent), Huntington State Beach (5 percent), and Tijuana Estuary (5 percent). Since 2005, the population has remained relatively static at about 7,000 pairs. In 2010 there were 6,568 pairs [8,9].

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan for the California least tern was issued in 1980 and revised in 1985 [1]. Its downlisting and delisting criteria incorporate the total population size, number of colonies, geographic distribution, population viability, and management status. To be downlisted to "threatened" status, the tern must have at least 1,200 breeding pairs distributed in at least 15 "secure" management areas. Each of these management areas must have at least one viable colony. The San Francisco Bay, Mission Bay and San Diego Bay management areas must have at least three, five, and four viable colonies respectively. To be viable, a colony must have at least 20 breeding pairs, a three-year mean reproduction rate of >= 1.0 fledglings/pair, and be fully protected under a long-term management plan. This would require a minimum of 24 viable colonies. To be recovered and delisted, the tern must have at least 1,200 breeding pairs distributed in at least 20 "secure" management areas. Each of these management areas must have at least one viable colony with a mean five-year reproduction rate of >= 1.0 fledglings/pair. The San Francisco Bay, Mission Bay and San Diego Bay management areas must have at least four, six, and six viable colonies respectively. This would require a minimum of 33 viable colonies.

The total population size of 1,200 breeding pairs for downlisting and delisting was reached in 1988 and all subsequent years. The downlisting criterion of 24 colonies was met in 1996 and all subsequent years. The delisting criterion of 33 colonies was met in 2003 and 2004. However, neither the downlisting nor delisting requirements for distribution and viability have been met. While human disturbance has been managed with fencing at most nesting areas, protection from native and non-native predators will require permanent management commitments to ensure continuing viability after the species is recovered and delisted [3].

In 2006, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a five-year review recommending the downlisting of the California least tern [5]. It acknowledged that all the downlisting criteria had not been achieved, but asserted that the recovery criteria were out of date. The downlisting recommendation was opposed by the Service biologist who prepared the five-year review [6].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Recovery Plan for the California Least Tern, Sterna Antillarum Browni. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. 112pg.

[2] Keane, K. 2005. California least tern monitoring 1969-2004. Spreadsheet provided by Kathy Keene, Keane Biological Consulting, Long Beach, CA on July 25, 2005.

[3] Keane Biological Consulting. 2004. Breeding Biology of the California Least Tern in the Los Angeles Harbor, 2004 Breeding Season. Prepared for the Port of Los Angeles, Environmental Management Division, under contract with the Port of Los Angeles, Agreement No. 2316.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Draft revised recovery plan for the California least tern. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carlsbad, CA.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. California least tern (Sterna antillarum browni) 5-year review summary and evaluation. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carlsbad, CA.

[6] Pagel, J. 2006. Letter from Joel Pagel, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to Scott Sobiech, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, dated August 23, 2006.

[7] Suckling, K. 2007. Personal observation, Kieran Suckling, Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ, October 1, 2007.

[8] Keane, K, N. Mudry and S. Langdon. 2011. Status Of The Endangered California Least Tern: Population Trends And Indicators For The Future. Presentation to the Least Tern Working Group annual meeting January 7, 2011.

[9] Marschalek, D. 2011. California Least Tern Breeding Survey 2010 Season. Available online at http://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentVersionID=59326, accessed September 13, 2011.

Brown pelican (Western Gulf Coast DPS) (Pelecanus occidentalis (Western Gulf Coast DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1980 |

Range: LA(b), MS(s), TX(b) ---

SUMMARY

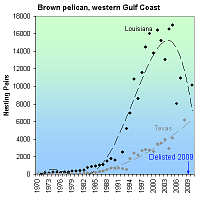

The brown pelican declined due to hunting, habitat loss and reproductive failure from eggshell thinning caused by the pesticide DDT. It continues to be threatened by offshore oil development, rising sea levels and hurricanes. It was listed as endangered in 1970. Nests in Texas increased from eight in 1970 to 6,136 in 2008. In Louisiana nests increased from 25 in 1971 to 17,000 in 2005 before Hurricane Katrina. It declined to 10,114 just prior to the gulf oil spill of 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The western gulf population of the eastern brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis carolinus) occurs along the Gulf of Mexico in Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. Outside the U.S., it occurs in Veracruz, the Yucatan Peninsula, Belize, the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Honduras, and the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama [1]. It was listed as an endangered species in 1970, and was delisted in 2009 due to recovery. It remains unseen how the 2010 BP oil spill will affect pelican populations on the Gulf Coast.

Louisiana: The brown pelican is the state bird. It bred in Louisiana in 1961, but then again until 1971 [2]. Birds from Florida were were reintroduced in 1968, 1969, and 1970, and they first bred in 1971 on a shell island in Barataria Bay near Grande Terre [5]. The population then steadily increased to a high of 17,000 nesting pairs in 2005 before Hurricane Katrin struck the Gulf Coast [4]. It declined to 8,036 the following year [4], then increased to 10,114 nests in 2010 just before Deepwater Horizon spill [6].

Texas: Nests increased from eight in 1970 to 6,136 in 2008 [4].

Mississippi: Pelicans roost and feed along the Gulf Coast and coastal islands of Mississippi, but there are no known records of pelicans nesting in the state.

CITATIONS

[1] Shields, M. 2002. Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 609 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Removal of the brown pelican in the southeastern United States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, February 4, 1985 (50 FR 4938)

[3] National Audubon Society. 2005. Pelecanus occidentalis, Brown Pelican. Website (www.audubon.org/local/latin/bulletin5/featured.html) visited December 30, 2005.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Removal of the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife (74 FR 59444).

[5] Shreiber, R.W. and R.W. Risebrough. 1972. Studies of the brown pelican. The Wilson Bulletin 8(2):119-135. Available at http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Wilson/v084n02/p0119-p0135.pdf

[6] Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. 2010. 2009-2010 Annual Report. Available at http://www.wlf.louisiana.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/publication/33881-2009-2010-annual-report/annual_report_2009-2010.pdf.

Great Lakes piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Great Lakes DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/10/2001 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 9/8/2003 |

Range: AL(s), FL(s), GA(s), LA(s), MI(b), MS(s), NC(s), SC(s), TX(s), VA(s), WI(b) --- IL(x), IN(x), MN(x), NY(x), OH(x), PA(x)

SUMMARY

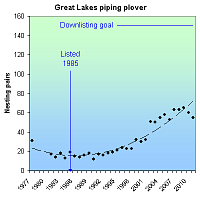

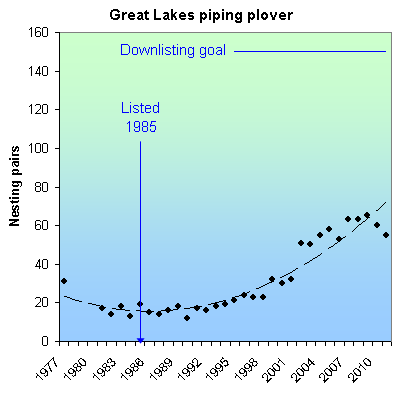

Early declines in Great Lakes piping plover populations were due to hunting, egg collecting and the millinery trade; later declines were the result of development, predation, and human recreation in plover nesting habitat. When the Great Lakes piping plover was listed as endangered in 1985, only 19 pairs remained. It increased to 55 pairs in 2011 and its range had expanded to the south, east and west.

RECOVERY TREND

The Great Lakes piping plover (Charadrius melodus) population breeds and raises its young on sparsely vegetated beaches, cobble pans and sand spits of glacially formed sand dune ecosystems along the Great Lakes shoreline [1].

It formerly nested in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Ontario. In the late-1800s the population may have been as large as 492 to 682 breeding pairs with 215 in Michigan, 152 to 162 in Ontario, 125 to 130 in Illinois, fewer than 100 in Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin and fewer than 30 in Minnesota, New York and Pennsylvania. Hunting, egg collecting and the millinery trade caused a late 19th-early 20th century population crash of many bird species until the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 put protections in place. How and when the Great Lakes population declined to its precariously small size at the time of listing is unknown [3]. However, conversion of nesting habitat to public recreation and general shoreline development are believed to have been important causes of the decline. By the late 1970s, the plover was essentially extirpated from Illinois, Indiana, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Ontario. It was extirpated from Wisconsin in 1983 and Minnesota in 1986, leaving just a small Michigan population.Impacts (e.g. development, recreation, beach stabilization) on the plover's wintering range also negatively affected birds from coastal North Carolina to Florida and along the Florida Gulf Coast to Texas, Mexico and the Caribbean Islands [4].

When the plover was listed as an endangered species in 1985, just 19 nesting pairs remained, all in Michigan [2]. The population fluctuated between 12 and 19 pairs between 1985 and 1993, then increased steadily to 55 pairs in 2011 [4]. The range expanded to the south, east and west, and plovers recolonized Wisconsin in 1998 at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Lake Superior, after being absent since 1983 [1]. The largest nesting congregation is at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Seashore, Mich., which typically supports about 25 percent of the population. The post-1993 increase was facilitated by aggressive management programs that protected nests from predators, nest areas from recreationists, and beaches from development. There is also a small captive rearing program focused exclusively on raising chicks hatched from abandoned eggs.

The 2003 federal recovery plan [1] establishes the following downlisting criteria: 1) a population of at least 150 pairs maintained over five consecutive years, with at least 100 breeding pairs in Michigan and 50 in other Great Lakes states; 2) a five-year average range-wide fecundity of 1.5 to 2.0 fledglings per pair; 3) a 10-year, post-downlisting projection of a stable or growing population. Delisting can occur when these population goals are paired with 1) a determination that genetic diversity is adequate, and 2) development of long-term funding and management agreements to ensure the population is adequately protected in its breeding and wintering range.

Michigan has attained 50 percent of its 100-pair breeding goal for four consecutive years [2]. The five-year average fecundity goal has been met. However, breeding in other Great Lakes states is limited to one to twopairs in Wisconsin.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Recovery Plan for the Great Lakes Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus). Ft. Snelling, Minnesota. viii + 141 pp.

[2] University of Minnesota Great Lakes Piping Plover Research Program. 2006. Summary of Great Lakes piping plover reproductive success 1984-2005. Spreadsheet provided by Francie Cuthbert, University of Minnesota, February 6, 2006.

[3] Cuthbert, F. 2006. Personal communication with Francie Cuthbert, Great Lakes Piping Plover Research Program, University of Minnesota, February 6, 2006.

[4] Cavalieri, V. 2012. Great Lake Piping Plover: Status of the Population and Recovery Program. Presentation presented at Northern Great Plains Piping Plover Workshop, December, 2011. Available at www.fws.gov/northdakotafieldoffice/endspecies/2011%20Northern%20Great%20Plains%20Plover%20papers/CavalieriGreat%20Lakes.pdf.

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/11/1984 | Recovery plan: 9/28/1990 |

Range: GU, MP

SUMMARY

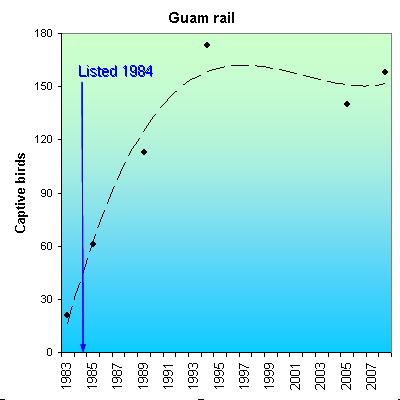

The Guam rail is threatened by predation by brown tree snakes, feral cats and other introduced species. It declined catastrophically from 18,000 to less than 100 birds between 1968-1983 as brown tree snakes spread across the island. Only two wild birds were seen after it was listed as endangered in 1984. It was extirpated from the wild in 1985. The captive population grew from 21 birds in 1983 to 158 in 2008. Still extant wild populations were created 1989 (Rota) and 2010 (Guam).

RECOVERY TREND

The Guam rail, or ko‘ko‘, (Rallus owstoni) is a flightless bird endemic to the island of Guam, a U.S. territory at the southern end of the Mariana Islands chain. It formerly occurred island-wide in most nonwetland habitats [5].

Though habitat loss, hunting and DDT spraying may have reduced its population level to some degree, the rail was estimated at 80,000 birds in the 1960s [13] and was still common as of 1969 [1]. Thereafter it suffered what may be the most rapid, catastrophic population decline of any U.S. bird species. The decline began in southern Guam in 1971, resulting in its extirpation there in the mid-1970s [1]. In northern Guam the decline began in 1972, resulting in the complete extirpation of the species from the wild by 1986 [1, 5].

Between 1976 and 1982, roadside rail counts declined by 99.8 percent (80.4/100 km to 0.2) [7].

The Guam rail’s rapidly shrinking range mirrors the expanding range of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), a native of Indonesia, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and northern Australia [18]. It was positively identified on Guam in the 1950s, but may have been seen in the 1940s, and was likely transported from the Admiralty Islands by the U.S. military during a large World War II buildup. The rail disappeared from areas where snake densities reached high levels, until the very last low-snake density area in extreme northwest Guam was overrun in the late 1970s. It was not alone: The brown tree snake had a devastating effect on all of Guam's native forest birds, resulting in all 12 being listed as endangered by the territory in the 1970s and eight of them by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1970, 1977 and 1984.

Though extirpated from the south, the Guam rail remained well distributed and fairly common in the north in 1976 and 1978 [14]. By 1981, though, it was reduced to about 2,300 birds, with the largest concentration on Andersen Air Force Base [2, 5]. By 1983, it was confined to two isolated populations totaling fewer than 100 birds: the Northwest Field (a military landing strip not used since 1949) and the flightline of Andersen Air Force Base [3, 5, 8].

By March 1984, rails were extremely rare in the Northwest Field and the flightline population, though the largest remaining, was reduced to 70 acres [4, 5]. The latter was also threatened by a land-clearing proposal, prompting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to emergency-list the Guam rail as an endangered species in April 1984 [9] and finalize the listing in August 1984 [8].

Following its listing, the Guam rail was seen twice in the wild: one bird in 1985 and another in 1986 [5, 16].

CAPTIVE BREEDING AND REINTRODUCTION

By 1983 the rail’s plight was so dire that a captive-breeding program was initiated by the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. Between 1983 and the cessation of captures in 1985 owing to the disappearance of wild birds, 21 rails were brought into captivity [5, 11, 15, 16]. These are the sole founders of all rails in existence today.

Beginning in 1984, captive rails were transferred to mainland facilities [5] and now occur in at least 17 facilities on Guam and the mainland [6, 11]. The first successful reproduction in captivity occurred in 1984 in the Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources facility [5].

In 1983 there were 21 birds in captivity [11], in 1985, 61 [5], in 1989, 113 [15], in 1994, 173 [11], in 2005, 140 [12] and in 2008, 158 [6].

GUAM - ANDERSEN AIR FORCE BASE

Guam rails have twice been released on Andersen Air Force Base, but neither effort resulted in a persisting population [6]. In 1998, 16 birds were released in Area 50, a 60-acre zone surrounded by a snake barrier and managed internally with snake trapping. Rails bred in the wild, but their population was extirpated by feral cats and other predators sometime before 2008.

In 2003, 44 rails were released into a snake-reduced zone within the Air Force Munitions Storage Area [6]. Feral cats killed 80 percent of radio-collared birds. Efforts to eliminate the cats were hampered by lack of permission. The population is believed to have been extirpated sometime before 2008 [6].

GUAM - COCOS ISLAND

On November 15, 2010, 16 captive-bred ko‘ko‘ birds were released into the wild on Cocos Island, on lands managed by the Cocos Island Resort and the Guam Department of Parks and Recreation [17]. No brown tree snakes exist on the island. Rats were eradicated prior to the release.

ROTA

Between 1989 and 2008, 918 Guam rails were introduced to the island of Rota [6]. Though Rota is near to, and has essentially the same habitat as, Guam, it is outside the rail’s historic range. The Fish and Wildlife Service very rarely introduces an endangered species outside its historic range, but was driven to do so because of the ubiquitous presence of brown tree snakes throughout Guam and the dominance of feral cats in the few places where snake levels have been reduced. If successful, establishment of wild rails on Rota will help preserve a wild genetic makeup under natural selection pressures and potentially provide a source of wild-born rails for a future Guam reintroduction.

Reproduction in the wild in Rota was first documented in 1995 [6]. In 2007 the population consisted of 60-80 birds in the Duge and Apanon areas. Predation by feral cats, however, is the population's primary cause of mortality, requiring cat control and continued introduction of captive bred birds to maintain the population [6].

[1] Jenkins, J.M. 1979. Natural history of the Guam rail. Condor 81:404-408.

[2] Engbring, J. and F.L. Ramsey. 1984. Distribution and abundance of the forest birds of Guam: Results of a 1981 survey. U.S. Fish Wildlife Service FWS/OBS-84/20.

[3] Aguon, C.F. 1983. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam. IN: Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, Annual Report, FY 1983. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

pp 143-157.

[4] Beck, R.E., Jr. 1984. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam. IN: Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, Annual Report, FY 1984. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

Pp 139-150.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990. Native Forest Birds of Guam and Rota of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Island Recovery Plan. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu, HI. Available at: http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plans/1990/900928b.pdf

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Ko‘ko‘ or Guam Rail (Gallirallus owstoni) 5-Year Review, Summary and Evaluation https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2529.pdf

[7] Aguon, C.F. 1982. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam and Northern Marianas Islands. IN: Guam Aquatic Wildlife and Resources Division Annual Report, FY 1982. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Determination of endangered status for seven birds and two bats on Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. July 27, 1984 (49 FR 33881). http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr875.pdf

[9] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Determination of endangered status for the Guam rail. April 11, 1984 (49 FR 14354). http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr814.pdf

[10] Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. 2012. Guam Rail / Ko‘ko‘. Website http://www.guamdawr.org/learningcenter/factsheets/birds/rail_html. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[11] Haig, S.M., and J.D. Ballou. 1995. Genetic Diversity in Two Avian Species Formerly Endemic to Guam. The American Ornithologists Union. 112(2):445-455.

[12] Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. 2005. Guam Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy. http://www.guamdawr.org/Conservation/gcwcs2/GuamCWCS%20Chapter3.pdf

[13] Lint, K.C. 1968. A rail of Guam. Zoo Nooz 41:16-17

[14] Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner and D.G. Berret. 1979. America's unknown avifauna: The birds of the Mariana Islands. American Birds 33(3):227-235.

[15] Haig, S.M., J.D. Ballou and S.R. Derrickson. 1990. Management options for preserving genetic diversity: Reintroduction of Guam rails to the wild. Conservation Biology 4(3):290-300.

[16] Haig, S. M., Ballou, J. D. and N. J. Casna. (1994) Identification of kin structure among Guam rail founders: A comparison of pedigrees and DNA profiles. Mol. Evol., 3:109-119.

[17] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Guam Rail / Gallirallus owstoni / Ko‘ko‘. Website: http://www.fws.gov/pacificislands/fauna/guamrail.html. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[18] Enbring, J. and T.H. Fritts. 1988. Demise of an insular avifauna: the brown tree snake on Guam. Transactions of the Western Section of the Wildlife Society 24:31-37.

Hawaiian common moorhen (`alae `ula) (Gallinula chloropus sandvicensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

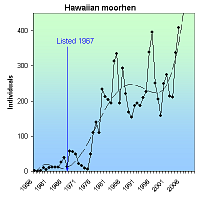

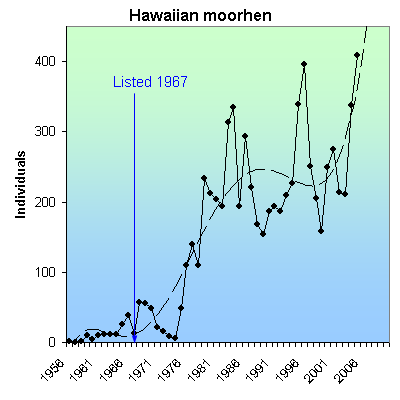

The Hawaiian common moorhen declined due to destruction and degradation of its wetland habitat. Though absolute abundance numbers are not clear, the species growth rate was sharply positive from 1956 through the mid-to-late 1980s, then increased more slowly through 2007.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus sandvicensis) was common on the main Hawaiian islands except Lana`I and Kaho`olawe in the late 19th century. By the late 1940s it was described as "precarious," especially on Oahu, Molokai, and Maui [1]. The Molakai population was extirpated after the 1940s, reintroduced in 1982, but did not persist and is currently absent from the island [1]. The spread of aquaculture on Oahu and Kauai in the late 1970's and the 1980's likely benefited the species. Aquaculture projects currently support some of the highest concentrations of moorhens in the state [1].

The population was estimated at no more than 57 in the 1950s and 1960s [2] and about 750 in 1985 (500 on Kauai, 250 on Oahu, and a small number on Molokai) [3], but this may be an underestimate [2]. The accuracy of these estimates is unclear because the species is very secretive and not conducive to standard waterbird census methods. Annual winter waterbird counts between 1956 and 2007, however, show a sharp, statistically significant increase through the mid-to-late 1980s, then a slower increase through 2005 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Draft of Second Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. 155 pp.

[2] Engilis, A., Jr., and T. K. Pratt. 1993. Status and population trends of Hawaii's native waterbirds, 1977-1987. Wilson Bull. 105:142-158

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Recovery Plan for the Hawaiian Waterbirds. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

[4] Reed, J. M., C. S. Elphick, E.N. Leno, and A.F. Zuur. 2011. Long-term population trends of endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. Popul Ecol (2011) 53:473–481.

Hawaiian coot (`alae ke`oke`o) (Fulica alai)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

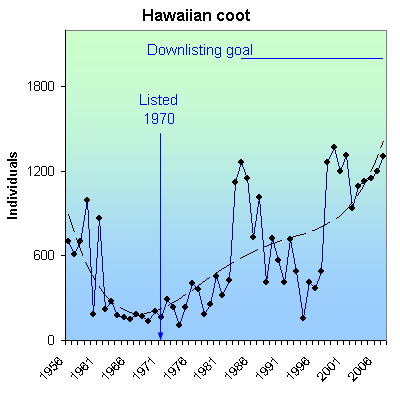

The Hawaiian coot was initially threatened by hunting in the first half of the last century, but is now threatened primarily by loss of habitat. The Hawaiian coot has increased from 1,000 birds on an extinction trajectory in the 1960's to over 2,000 birds today.

RECOVERY TREND

Hawaiian coots (Fulica alai) historically occurred on all of the main Hawaiian Islands except Lana'i and Kaho`olawe, which lacked suitable wetland habitat [1]. They are known to have been most numerous on Kaua'i, Maui and O'ahu, but there are no historical population estimates. The population was low enough in 1939 to warrant establishment of a permanent hunting ban [2]. In the 1950s the coot was considered to be on a trajectory towards extinction. Fewer than 1,000 birds were thought to remain by the late 1960s.

Hunting was a significant threat until outlawed in 1939 [2]. Habitat loss is now the primary cause of endangerment. For example, Ka‘elepulu Pond on O‘ahu, supported nearly 1,000 coots until it was dredged and surrounded by mowed lawns and cement in the 1940s as part of the Enchanted Lake subdivision [2]. The current population is much smaller. Conversely, the species has expanded into unusual habitats such as sewage-treatment plants at Kailua-Kona, Hawaii; Lana‘i City, Lana‘i; and Kuilima, O‘ahu [2].

Biannual surveys indicate short-term population fluctuations associated with rainfall [1]. The 2005 population was estimated at about 2,100 birds with 80 percent of birds on Kaua’i, O'ahu and Maui. All the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho`olawe are currently occupied. The 2012 Recovery Plan states that based on the most recent data available (2008), populations have recently fluctuated between approximately 1,500 and 2,800 birds and have averaged 2,000 birds [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Revision. Portland, Oregon. October 28, 2011.

[2] Brisbin, I. L., Jr., H. D. Pratt, and T. B. Mowbray. 2002. American Coot (Fulica americana) and Hawaiian Coot (Fulica alai). In The Birds of North America, No. 697 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[3] Reed, J. M., C. S. Elphick, E.N. Leno, and A.F. Zuur. 2011. Long-term population trends of endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. Popul Ecol (2011) 53:473–481.

Hawaiian duck (koloa maoli) (Anas wyvilliana)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

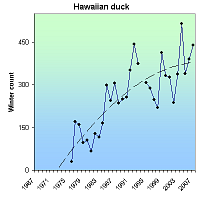

The Hawaiian duck was endangered by hunting, non-native predators, hybridization with domestic ducks, and habitat loss. By 1962, it had been extirpated from all the Hawaiian Islands except Kauai where a few hundred birds remained. In 2002, there were 2,300 birds on Kauai (2,000) and Hawaii (300), and unknown numbers on Oahu and Maui.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian duck (Anas wyvilliana) breeds in montane streams and feeds and loafs in lowland wetlands. It historically occurred on all the main Hawaiian Islands except Lana`i and Kaho`olawe, which have little surface water.

Suitable stream habitats have declined since humans arrived on the islands some 1,600 years ago [1]. Wetlands may have initially increased due to cultivation of taro and rice, but it unknown how duck populations would have responded to the combination of increased wetlands and efforts to keep them from consuming crops. From the late 19th century to fairly recently, wetlands have steadily declined due to development, changes in agriculture practices, and introduced pigs and goats [1].

Hawaiian ducks were also harmed by human hunting, predation of eggs and chicks by introduced rats, mongooses, dogs, cats, fish and birds. Hybridization with feral mallards that escaped from commercial farms established on Oahu in the 1930s and 1940s continues to threaten the species. Hybridization is also a problem on Kaua`i and Hawaii.

The Hawaiian duck was fairly common in the 19th century, but was rare in many places and generally declining in the early 20th century [3]. By 1949 it was extirpated from Maui and Molokai, rarely seen on Hawaii, and reduced to just 500 birds on Kauai, 30 on Oahu, and possibly some birds on Niihau [1]. By 1962 it occurred only on Kauai [3]. The Kauai population declined significantly between 1956 and 1982 [4]. A State of Hawaii captive breeding program reintroduced the species to the Kohala Mountains on the island of Hawaii from 1958 to 1980, resulting in a current population of about 200 birds that utilize stock ponds, streams and the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge [1, 3]. Hybridization is occurring in both high- and low-elevation sites [1].

A total of 326 Hawaiian ducks were reintroduced to Oahu by the state between 1968 and 1980 [3]. The introduction site was occupied by feral mallards, and no mallard-control program was initiated. Most of the current population is believed to be hybridized, with suspected pure birds declining and suspected hybrids increasing in recent years [1]. The state introduced 12 Hawaiian ducks to Maui in 1989 and 1990, but did not control existing mallard populations [1, 3]. There are currently 20-50 birds on the island, mostly at Kanaha Pond, and most, if not all, are hybridized [1, 3].

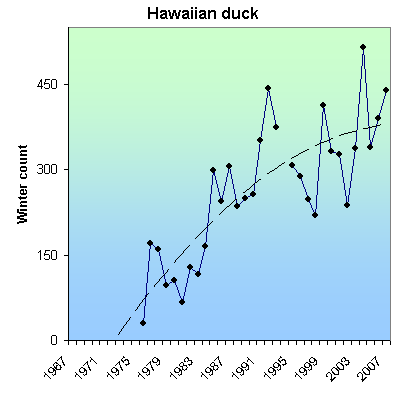

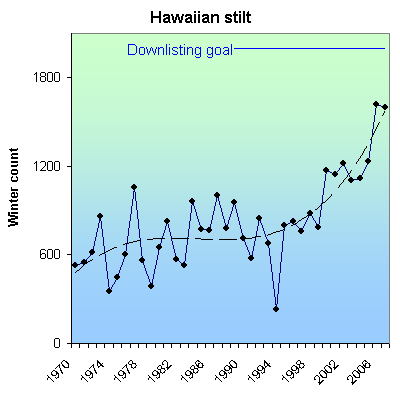

Biannual summer and winters surveys indicate a population increase between 1967 and 2007, with the Kauai population increasing and others declining due to hybridization [1]. The most recent estimate is from 2002 of 2,200 birds on Kauai (2,000) and Hawaii (200) and unknown numbers of pure birds within the 300 Hawaiian duck-like birds on Oahu and 50 on Maui. [3]. The 2011 federal recovery plan concludes that the population is increasing, but the most recent rangewide estimate is still from 2002 [1].