Aleutian Canada goose (Branta hutchinsii leucopareia)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/30/1991 |

Range: AK(b), CA(s), OR(s), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

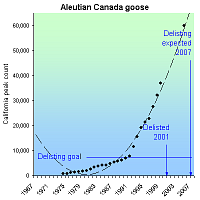

In the 1960s the Aleutian Canada goose was feared extinct due to predation by non-native foxes introduced to its nesting island, and to a less degree, by excessive hunting and loss of winter and migration habitat. It was rediscovered in 1962. In 1967 it was listed as an endangered species and grew from ~790 birds in 1975 to ~60,000 in 2005. It was declared recovered and removed from the endangered list in 2001, seven years earlier than projected by its recovery plan.

RECOVERY TREND

The Aleutian Canada goose was an abundant subspecies of Canada goose that nested in the northern Kuril and Commander Islands, in the Aleutian Archipelago, and on islands south of the Alaska Peninsula east to near Kodiak Island [1]. The birds wintered in Japan and in the coastal western United States to Mexico [1].

The fur industry began introducing Arctic and red foxes to the goose's nesting islands 1750, reaching a peak between 1915 and 1939 [2]. Foxes were released on 190 islands within the Aleutian Canada goose’s breeding range in Alaska [1]. They decimated the species by predating heavily on eggs, goslings and flightless molting geese.

Hunting, especially on the migration and wintering range in California, also contributed to population declines, as did loss and degradation of migration and wintering habitat [1]. Between 1938 and 1962, there were no sightings of Aleutian Canada geese, and it was feared the subspecies had gone extinct [1]. In 1962, however, a remnant population was discovered on rugged, remote Buldir Island in the western Aleutians [2].

After the Aleutian Canada goose was listed as endangered, efforts to eliminate introduced foxes from former nesting islands and to reintroduce the geese were initiated [1]. Hunting closures were implemented in wintering and migration areas [3]. Also, in the early 1980s biologists discovered two additional islands that supported small numbers of breeding Aleutian Canada geese [1].

Although early releases of captive-reared geese proved largely unsuccessful due to low survival rates, populations began to increase, likely due to the hunting closures in California and Oregon [1]. Translocations of wild-caught geese, implemented when the population on Buldir Island became large enough, proved more successful and as new breeding colonies became established, numbers increased rapidly [1]. In addition, important wintering and migration habitat in California and Oregon was acquired and designated as national wildlife refuges, and local landowners were encouraged to protect and manage habitat [2].

By 1990, the population had increased to an estimated 6,300, up from 790 counted in 1975, and the species was downlisted from endangered to threatened [1]. Between 1990 and 1998, the average annual population growth rate was estimated at 20 percent, and new populations became firmly established on Agattu, Alaid and Nizki islands in the western Aleutians [2]. In 1999, the population reached more than 30,000 [3]. In 2001, with the population estimated at 37,000, the Fish and Wildlife Service declared the Aleutian Canada goose recovered, and the species was taken off the list of endangered species [1]. In 2005 the population was approximately 60,000 [4]. While the Aleutian Canada goose continues to rebound in the western Aleutians, Russian scientists are conducting an ongoing program to reestablish it in the Asian portion of the birds’ range [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Rule to Remove the Aleutian Canada Goose From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register (66 FR 15643).

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. An Endangered Species Success Story: Secretary Norton Announces Delisting of Aleutian Canada Goose. News Release, March 19, 2001. Available at <http://news.fws.gov/newsreleases/R9/571EA0D1-2270-400B-B350418F893BCCEC.html?CFID=1629288&CFTOKEN=63346966>

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Aleutian Canada Goose Road to Recovery Timeline. Available at <http://alaska.fws.gov/media/pdf/road-to-recovery.pdf>.

[4] Trost, R. E., and M. S. Drut. 2005. 2005 Pacific Flyway data book: waterfowl harvests and status, hunter participation and success, and certain hunting regulations in the Pacific Flyway and United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Portland, Oregon.

American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 8/11/1977 |

| Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(b), AR(m), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(m), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(m), KY(b), LA(m), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(m), MO(m), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(m), OH(b), OK(m), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(m), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

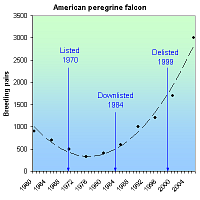

The use of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides thinned American peregrine falcon eggshells, causing reproductive failure and population declines. The banning of DDT, captive-breeding efforts and nest protections allowed falcons to increase from 324 breeding pairs in 1975 to 3,005 pairs as of 2006. The species was delisted in 1999.

RECOVERY TREND

The American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) breeds only in North and Central America and occurs throughout much of North America from the subarctic boreal forests of Alaska and Canada south to Mexico [1]. It is estimated that prior to the 1940s, there were approximately 3,875 nesting pairs of peregrines in North America [1]. From the 1940s through the 1960s, however, the population of the peregrine, and many other raptors, crashed as a result of the introduction of synthetic organochlorine pesticides to the environment. By 1975, there were only 324 known nesting pairs of American peregrine falcons in the U.S. [2].

Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [1]. Organochlorine pesticides were put into use following World War II. Use peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s and continued through the early 1970s [1]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey because they ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches [1]. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. During the period of DDT use in North America, eggshell thinning and nesting failures were widespread in peregrine falcons, and in some areas, successful reproduction virtually ceased [1].

The degree of exposure to these pesticides varied among regions, and peregrine falcon numbers in more contaminated areas suffered greater declines [1]. The eastern population plunged from an estimated 350 active nest sites in the 1930s and 1940s to no active breeding birds from 1964 to 1975 [3]. Peregrine falcons in the Great Plains states east of the Rocky Mountains and south of U.S. and Canadian boreal forests were also essentially extirpated [1]. West of the 100th meridian, peregrine falcons were significantly reduced [1]. Local populations were greatly depressed or extirpated and by 1965 fewer than 20 pairs were known west of the U.S. Great Plains [1].

In 1970, the American peregrine was listed as endangered and efforts to recover the species began. The use of DDT was banned in Canada in 1970 and in the United States in 1972 [1]. This was the single-most significant action in the recovery of the peregrine falcon [1]. In addition, in the eastern United States, efforts were made to reestablish peregrine falcons by releasing offspring from a variety of wild stocks that were held in captivity by falconers [1]. The first experimental releases of captive-produced young occurred in 1974 and 1975 in the eastern United States [1]. These and future releases demonstrated that “hacking,” the practice of retaining and feeding young captive bred birds in partial captivity until they are able to fend for themselves, was an effective method of introducing captive-bred peregrines to the wild [1]. Since then, more than 6,000 falcons have been released in North America [1]. Approximately 3,400 peregrines were released in parts of southwest Canada, the northern Rocky Mountain States, and the Pacific Coast states [1].

In the late 1970s, Alaska became the first place American peregrine falcon population growth was documented and, by 1980, populations began to grow in other areas [1]. Not only did the number of peregrine falcons begin to increase, productivity (another important measure of population health) improved [1]. Efforts to reestablish peregrine falcons in the East and Midwest proved largely successful, leading to downlisting of the species in 1984 [1], and by 1999 peregrines were found to be nesting in all states within their historical range east of the 100th meridian, except for Rhode Island, West Virginia and Arkansas [1]. In highly urban areas, peregrine falcons showed great adaptability, and began substituting skyscrapers for natural cliff faces as nesting sites [4]. By 1998, the total known breeding population of peregrine falcons was 1,650 pairs in the United States and Canada, far exceeding the recovery goal of 456 pairs. Other recovery goals, including estimates of productivity, egg-shell thickness, and contaminants levels, had also been met, allowing the species to be delisted in 1999 [1]. Monitoring of American peregrine populations has continued under a post-delisitng monitoring plan [5]. The estimated North American population was 3,005 pairs as of 2006 [6].

ALASKA: Surveys conducted between 1966 and 1998 along the upper Yukon River demonstrated increases in the number of occupied nesting territories from a low of 11 known pairs in 1973 to 46 pairs in 1998 [1]. Similarly, along the upper Tanana River, the number of occupied nesting territories increased from two in 1975 to 33 in 1998 [1]. The recovery objective of 28 occupied nesting territories in the two study areas was first achieved in 1988, with 23 nesting territories on the Yukon River and 12 on the Tanana River [1].

PACIFIC STATES: By 1976, no American peregrine falcons were found at 14 historical nest sites in Washington [1]. Oregon had also lost most of its peregrine falcons and only one or two pairs remained on the California coast [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 to 1998 indicated a steadily increasing number of American peregrine falcon pairs breeding in Washington, Oregon and Nevada [1]. Known pairs in Washington increased from 17 to 45 and in Oregon from 23 to 51 [1]. The number of American peregrine falcons in California increased from an estimated low of five to 10 breeding pairs in the early 1970s to a minimum of 167 occupied sites in 1998 [1]. The increase in California was concurrent with the restriction of DDT and included the release of more than 750 American peregrine falcons through 1997 [1].

ROCKY MOUNTAINS/SOUTHWEST: The Rocky Mountain/Southwest population of the American peregrine falcon has made a profound comeback since the late 1970s when surveys showed no occupied nest sites in Idaho, Montana or Wyoming and only a few pairs in Colorado, New Mexico and the Colorado Plateau, including parts of southern Utah and Arizona [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 through 1998 indicated that the number of American peregrine falcon pairs in the Rocky Mountain/Southwest area has steadily increased [1]. In 1991, there were 367 known pairs; in 1998 the number of pairs increased to 535 [1].

EASTERN STATES: The eastern peregrine population has a unique history and complex status under the Act [1]. Peregrine falcons were extirpated in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada by the mid-1960s [1]. Releases of young captive bred peregrines have reestablished populations throughout much of their former range in the East [1]. In 1998, 193 pairs were counted in five designated eastern state recovery units [1]. The number of territorial pairs recorded in the eastern peregrine falcon recovery area increased an average of 10 percent annually between 1992 and 1998 [1]. Equally important, the productivity of these pairs during the same seven-year period averaged 1.5 young per pair, demonstrating sustained successful nesting [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Final Rule to Remove the American Peregrine Falcon from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, and to Remove the Similarity of Appearance Provision for Free-Flying Peregrines in the Conterminous United States. Federal Register (64 FR 46542).

[2] Hoffman, C. 1999. The Peregrine Falcon is Back! New release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 20, 1999.

[3] Clark, K. 2005. The Peregrine Falcon in New Jersey, Report for 2005. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program.

[4] New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. Fact sheet, Peregrine Falcon Falco pereginus. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program. Website <http://www.njfishandwildlife.com/tandespp.htm> accessed February, 2006.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Monitoring Plan for the American Peregrine Falcon, A Species Recovered Under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Endangered Species and Migratory Birds and State Programs. Pacific Region, Portland Oregon 53pp.

[6] Green, M., T. Swem, M. Morin, R. Mesta, M. Klee, K. Hollar, R. Hazelwood, P. Delphey, R. Currie, and M. Aramal. 2006. Monitoring Results for Breeding American Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus anatum), 2003. Biological Technical Publication BTP-R1005-2006. U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(m), AR(m), CA(m), CO(m), CT(m), DE(m), DC(m), FL(m), GA(m), ID(m), IL(m), IN(m), IA(m), KS(m), KY(m), LA(m), ME(m), MD(m), MA(m), MI(m), MN(m), MS(m), MO(m), MT(m), NE(m), NV(m), NH(m), NY(m), NM(m), NJ(m), NC(m), ND(m), OH(m), OK(m), OR(m), PA(m), RI(m), SC(m), SD(m), TN(m), TX(m), UT(m), VT(m), VA(m), WA(m), WV(m), WI(m), WY(m) ---

SUMMARY

The Arctic peregrine falcon declined due to the egg shell-thinning effects of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides. Its listing as an endangered species in 1970 (along with other birds of prey) prompted the EPA to ban DDT in 1972. Counts of migratory Arctic falcons increased from 103 in 1976, to 1,017 in 2004. The species was downlisted to threatened in 1984 and delisted in 1991.

RECOVERY TREND

The Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius) is one of three peregrine falcon subspecies [1]. It nests in tundra regions of Alaska, Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Quebec, and possibly Labrador), and the ice-free perimeter of Greenland [1]. It is a long-distance migrant that winters in Latin America from Cuba and Mexico south through Central and South America [1].

Severe declines in peregrine falcon numbers began in the 1950s [1]. These declines were linked to organochlorine pesticides that were put into use following World War II, and whose use peaked in the late 1950s-early 1960s [1]. Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [2]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey which, being at the top of the food chain, ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. Arctic peregrine numbers reached their lowest levels in the early 1970s and in some areas of North America successful reproduction virtually ceased [1]. Populations are thought to have decreased by as much as 80 percent [2].

The listing of the Arctic peregrine falcon as endangered in 1970--as well as the bald eagle, brown pelican, and American peregrine falcon shortly before--fostered a national outcry against the production and spaying of DDT. In 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency banned most used of DDT in the United States [1]. Canada had already restricted DDT use in 1970. These restrictions are the central cause of the recovery of the Arctic and American peregrine falcons (the bald eagle and brown pelican benefited greatly as well, but their recovery also involved substantial habitat protections and reintroductions).

As DDT levels declined after 1972, peregrine falcon productivity rates rose to pre-DDT levels and the population size and range began to increase. This happened most rapidly in northern areas, where pesticide exposur was lower and impacts upon populations were less severe [1]. In 1984, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service downlisted the Arctic peregrine falcon from endangered to threatened status [2, 6]. In 1991, the agency initiated a review determine if the species had recovered [2] and in 1994 removed it from the endangered species list [6].

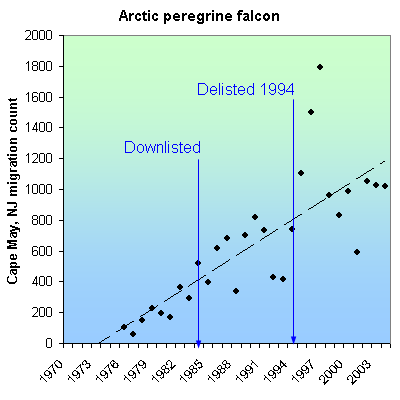

Four major factors were considered in the delisting process: (1) Population size and trend, (2) reproductive performance, (3) pesticide residues in eggs, and (4) eggshell thickness [1]. Despite a lack of long-term studies using consistent methodologies, there was strong evidence of significant population increases throughout the Arctic [1]. Four areas in northern North America (one in Alaska and three in Canada’s North West Territories) for which historical survey information was available indicated the number of Arctic peregrine pairs occupying nesting territories increased since the 1960s [1]. Some areas of Alaska even exceeded the original estimates of pre-DDT-era population size [1]. In addition, in the eastern Arctic, peregrines began nesting in previously vacant nesting sites [1]. Standardized yearly migration counts at New Jersey’s Cape May, an area where Arctic peregrines concentrate during migration, also saw increasing numbers, most likely from Arctic breeding grounds especially in Greenland and eastern Canada (these counts may have also contained peregrines in the American subspecies; however, banding recoveries indicate that the majority of peregrines along the East Coast during fall migration are from the Arctic and thus represent a true increase in Arctic peregrine numbers) [1].

Productivity in all regions where data had been gathered was sufficient to support a stable or increasing population since the 1980s [1]. There had also been improvements in levels of DDE concentration in eggs. Concentrations in excess of 15-20 parts per million (wet weight basis) are associated with high rates of nesting failure. Residue in eggs in 1993 was well below this critical level [1]. Alaskan eggshells collected between 1988 to 1991 were on average only 12 percent thinner than pre-DDT thickness (17 percent or greater reduction in thickness results in population declines).

Arctic peregrine falcon numbers have continued to rise after the species' delisting. On the Sagavanirktok River in Alaska, where Arctic peregrine surveys have been conducted since the late 1950s, the number of pairs increased from five in 1958, to 23 in 1992, to 25 in 1999 [3]. Migration counts at the Cape May Hawkwatch site in New Jersey increased from 103 in 1976 to 1,024 in 2003 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Proposal to Remove the Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 58 Fed. Reg 188.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Peregrine falcon, (Falco peregrinus anatum, Falco peregrinus tundrius, Falco peregrinus pealei). Species account. Website <http://www.fws.gov/species/species_accounts/bio_pere.html> accessed October, 2005.

[3] Wright, J.M. and P.J. Bente. 1999. Documentation of active peregrine falcon nest sites, 1 Oct 1994- 31 March 1998. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Annual research report. Endangered species conservation fund federal aid project SE-2-9, 10, and 11. Juneau, AK. 15 pp.

[4] Cape May Bird Observatory. 2012. Cape May Hawkwatch, Cape May, New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society. Website <http://www.njaudubon.org/Sightings/cmhw25.html> accessed April 2, 2012.

[5] NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Removal of Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 50796.

Bald eagle (continental U.S. DPS) (Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Continental U.S. DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(b), AZ(b), AR(b), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(b), FL(b), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(b), KY(b), LA(b), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(b), MO(b), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(b), OH(b), OK(b), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(b), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

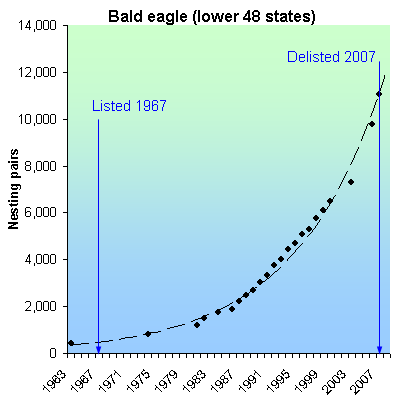

The bald eagle declined throughout the lower 48 states, and was extirpate from most of them due to habitat loss, persecution, and DDT-related eggshell thinning. The banning of DDT, increased wetland protection and restoration, and an aggressive, mostly state-based reintroduction program caused eagle pairs to soar from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when the eagle was removed from the endangered list.

RECOVERY TREND

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) first declined in the 1800s at the hands of trophy hunters, feather collectors, and wanton killing [1]. It was already extirpated or at low numbers in most states by the 1940s when DDT and other organochlorines became widely used. DDE, a breakdown product of DDT, accumulates in the fatty tissue of female eagles, impairing the formation of calcium needed for normal egg formation, causing a decline in reproductive success. DDT caused eagle numbers plummet further, and in 1967 the species was listed as endangered in the lower 48 states [1].

The eagle was joined on the list by the American peregrine falcon, Arctic peregrine falcon and brown pelican in 1970. The listing of these large, charismatic birds rallied the nation to band the production and sale of DDT in 1972.

Due to the DDT ban, increased habitat protection, and aggressive captive breeding and translocation programs (mostly run by state wildlife agencies), bald eagle pairs in the lower 48 soared from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when it was removed from the threatened species list [2, 7]. In 1984, 13 states lacked nesting eagles. By 1998, it was absent from only two. By 2006, it nested in all 48 states [7].

The eagle was proposed for delisting in 1998 [1] and again in 2006 [4]. It was downlisted in 1995 and delisted in 2007 [6].

The bald eagle is managed under five federal recovery plans, divided by region:

Chesapeake Recovery Region: Virginia east of Blue Ridge Mountains, Delaware, Maryland, the eastern half of Pennsylvania, West Virginia Panhandle and two-thirds of New Jersey. Delisting goals were met in 1996 [1]. As of 2003, there were more than 800 nesting pairs in this region [4].

Northern States Recovery Region: 25 Northernmost states. Delisting goals were met in 1991, with 1,349 occupied breeding areas across 20 states. As of 2007, there were an estimated 4,215 breeding pairs in the northern recovery region [6].

Pacific Recovery Region: Idaho, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Montana and Wyoming. Numeric delisting goals were met in 1995 [1]. As of 2001, there were

1,627 nesting pairs in this recovery region [4].

Southeastern Recovery Region: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and eastern Texas. Downlisting goals were met between 1991 and 1998. More than 1,700 pairs were counted in 2000 [4, 6].

Southwestern Recovery Region: Oklahoma and Texas west of the 100th meridian, New Mexico, Arizona and California bordering the Lower Colorado River. The goal established in the recovery plan has been exceeded. In 2003, 46 occupied breeding areas were reported in New Mexico and Arizona. In 2004, the Arizona had 41 occupied breeding areas [4].

In the eight Northeast states from New Jersey to Maine and Vermont, nesting eagle pairs increased from 21 in 1967 to 562 in 2005 [5]. The majority were in Maine, which supported all 21 pairs in 1967 and 385 pairs in 2005. Eagles returned to Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1990, with the former supporting 19 pairs in 2005 and the latter eight in 2004. In 2005 there were 53 pairs in New Jersey, 94 in New York and one in Vermont. The Northeast is also an important wintering area, with the Connecticut population increasing from 20 to 92 between 1979 and 2005, and the New York population increasing from six to 194 between 1978 and 2006 [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Proposed rule to remove the bald eagle in the Lower 48 states from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register, July 6, 1999 (64 FR 36453)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Bald Eagle Numbers Soaring. May 14, 2007 press release.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Removing the bald eagle in the Lower 48 States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife; reopening of public comment period with new information. Federal Regiter, February 16, 2006 (71 FR 8238).

[5] Center for Biological Diversity. 2006. Bald eagle trends in the Northeastern United States. Tucson, AZ.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Removing the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Final Rule. 72 Fed. Reg 37346.

[7] Suckling, K. and W. Hodges. Status of the bald eagle in the lower 48 states and the District of Columbia: 1963-2007. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ. Available at http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/bald_eagle/report/index.html.

Bighorn sheep (Peninsular Ranges DPS) (Ovis canadensis pop. 2)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 2/1/2001 | Listed: 3/18/1998 | Recovery plan: 10/25/2000 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

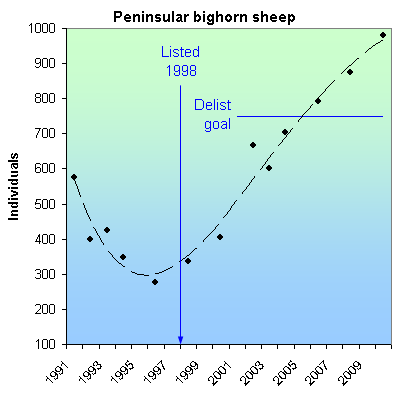

The Peninsular bighorn sheep declined to near extinction because of housing developments, agriculture, collisions with cars, predation by mountain lions and diseases contracted from domestic sheep. Sheep populations plummeted from 971 in 1971, to 276 in 1996, but since being listed as endangered in 1998, the number of bighorns has increased to 981 as of 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Peninsular bighorn sheep is a distinct population of bighorn (Ovis canadensis) that is restricted to east-facing, lower elevation slopes (typically below 4,600 feet) of the Peninsular Ranges along the northwest edge of the Sonoran Desert in southern California. Though populations occur in Mexico, the species is only listed as endangered from the San Jacinto Mountains south to the U.S.-Mexico border. It has declined due to loss of habitat to agriculture and housing development, car collisions, predation by mountain lions, diseases contracted from domestic sheep, disturbance by humans and dogs, fire suppression, and spread of exotic plants such as tamarisk [1]. It was listed as an endangered species in 1998. Critical habitat was designated on 844,897 acres in 2001, but was reduced to 376,938 acres in 2009 [3].

The historic population size is unknown, but the species was considered "rare" in 1971 when it was estimated at 971 animals [1]. The highest recent population was 1,171 animals in 1974 and 1979. The population plummeted to 276 in 1996 but following listing, increased to 981 as of 2010 [4]. Approximately 100 peninsular bighorn are captive-bred and used to augment the wild population [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. Recovery Plan for bighorn sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR. 251 pp.

[2] Bighorn Institute. 2005. Endangered Peninsular Bighorn Sheep, website (www.bighorninstitute.org/endangered.htm) accessed September 30, 2005.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Designation of Critical Habitat for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep and Determination of a Distinct Population Segment of Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni), Final Rule. 74 FR 17288.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Peninsular bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) 5 Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad, CA.

Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/23/1998 |

Range: AK(s), CA(s), FL(o), HI(s), ME(o), MD(o), MA(o), NH(o), NY(o), NC(o), OR(m), RI(o), SC(o), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

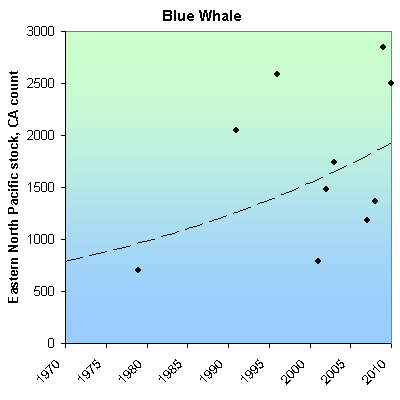

The blue whale population was reduced by as much as 99 percent due to whaling that occurred before the mid-1960s. The number of whales reported off the coast of California, the largest stock in U.S. waters, increased from 704 in 1980 to an estimated 2,497 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal ever known to have lived on Earth [1]. Blue whales are found in all oceans worldwide and are separated into populations from the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere [1]. Each population is composed of several stocks that typically migrate between higher-latitude summer feeding grounds and lower-latitude wintering areas. The largest numbers of blue whales in U.S. waters are within the eastern North Pacific stock. Other U.S. stocks occur in waters off the coast of Hawaii and the Northeast [1].

Pre-whaling blue whale populations had about 350,000 individuals [3]. In 1868, the invention of the exploding harpoon gun made the hunting of blue whales possible and in 1900, whalers began to focus on blue whales and continued until the mid 1960s [1, 3]. During this time, it is estimated that whalers killed up to 99 percent of blue whale populations [3]. Currently, there are about 5,000-10,000 blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere and about 3,000-4,000 in the Northern Hemisphere [3]. Current threats include collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced zooplankton production due to habitat degradation, and disturbance from low-frequency noise [1]. The offshore driftnet gillnet fishery is the only fishery likely to take blue whales, but few mortalities or serious injuries have been observed [2].

EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

The Eastern North Pacific Stock feeds in waters off the coast of California from June to November and then migrates south to Mexico (sometimes going as far south as Costa Rica) in winter/spring [2]. Recently, blue whales seen off the coast of Alaska were photo-matched to photos from the Southern California area, indicating that California animals now migrate as far north as Alaska [4]. This is probably a reestablishment of a traditional migratory route [4]. The number of whales reported off the coast of California increased from 704 in 1979/80 to 2497 in 2010 [2, 11]. It is not certain if the overall increasing trend indicates a growth in the size of the stock, or just increased use of California waters [2], but in general, the stock is thought to have increased [1]. Because this is the largest stock in U.S. waters, it dominates the trend of the species in U.S. waters.

WESTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

Blue whales feeding along the Aleutian Islands are probably part of a central western North Pacific stock that is thought to migrate to offshore waters north of Hawaii in winter [5]. Sightings of blue whales in Hawaiian waters are infrequent, although acoustic recordings indicate that blue whales occur there. There are no estimates of population size for this stock [5]. No blue whales were sighted during aerial surveys of Hawaiian waters conducted from 1993 to 1998 or during shipboard surveys conducted in the summer/fall of 2002 [5]. In 2004, three blue whales were seen in the western Aleutians, the first U.S. sightings of blue whales from this western North Pacific population in several decades [6]

NORTH ATLANTIC STOCK

The blue whale is an occasional visitor along the Atlantic coast of the Northeast [7]. Sightings of blue whales off Cape Cod, Mass., in summer and fall may represent the southern limit of the feeding range of the western North Atlantic stock that feeds primarily off the Canadian coast [7]. Blue whales have been sighted as far south as Florida, however, and the actual southern limit of this stock’s range is unknown [7]. Because blue whales are not frequently seen in U.S. Atlantic waters, there are insufficient data to determine the stock's population trend [7]. In 1997, the total number of photo-identified individuals for eastern Canada and New England was 352 [1].

CITATIONS

[1] NMFS. 1998. Recovery plan for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Prepared by Reeves R.R., P.J. Clapham, R.L. Brownell, Jr., and G.K. Silber for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 42 pp.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] American Cetacean Society. 2005 American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Website http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bluewhl.htm (accessed on 11/30/05).

[4] NOAA. Fisheries. 2004. NOAA Scientists Sight Blue Whales in Alaska. Press Release 7/27/2004.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[6] Rankin, Barlow and Stafford. (in press) Marine Mammal Science.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2002. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised Jan. 2002. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2007. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2008. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] NOAA Fisheries. 2009. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[11] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

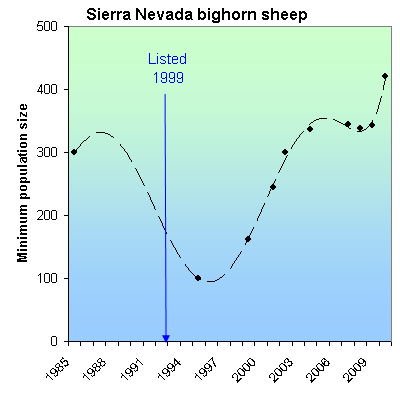

California bighorn sheep (Sierra Nevada DPS) (Ovis canadensis sierrae)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 8/5/2008 | Listed: 4/20/1999 | Recovery plan: 9/24/2007 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

The Sierra Nevada big horn sheep declined due to hunting, disease, introduction of domestic sheep, habitat loss and disturbance. It's historic population of more than 1,000 sheep declined to 300 in 1985 and 100 in 1995 prior to its emergency listing as an endangered species in 1999. Since then its population increased to at least 420 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae) formerly included 20 subpopulations on the eastern slope of California's Sierra Nevada, and at least one subpopulation on the western slope [1]. The historic population size is not well known, but has been estimated at 1,000 or more individuals [5]. It began declining in the mid-1800s due to hunting, disease and the introduction of domestic sheep. About half the subpopulations were gone by the early 1900s. The species continued dwindling to five populations in the 1950s and two in the 1970s [2].

The population was estimated at 250 in 1978 on Mount Williamson, Mount Baxter, and Sawmill Canyon, and 300 in 1985 (mostly In Mount Baxter and Sawmill Canyon) [1, 3, 4]. Thereafter it plunged to a historic low of 100 in 1995. After being listed as endangered in 1999 on an emergency basis, the bighorn's population increased to a minimum of about 350 in 2004, remained at this level through 2009, then increased to 420 in 2010 [5, 6, 7].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Draft Recovery Plan for the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. xiii + 147 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. Final rule to list the Sierra Nevada Distinct Population Segment of the California Bighorn Sheep as Endangered. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, January 3, 2000 (65 FR 20).

[3] Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation. 2000. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Population Status, Census Work 1995 On. www.sierrabighorn.org/endanger/population_status.htm

[4] Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation. 2002. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep 2002 Update, Herds Continue to grow. www.sierrabighorn.org/endanger/2002%20update.htm

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Recovery Plan for Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep. Portland, OR. xiv + 199 pp.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis californiana (=Ovis canadensis sierrae) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Portland, OR. 41 pp.

[7] Stephenson, T. R., et al. 2012. 2010-2011 Annual Report of the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program: A Decade in Review. California Department of Fish and Game.

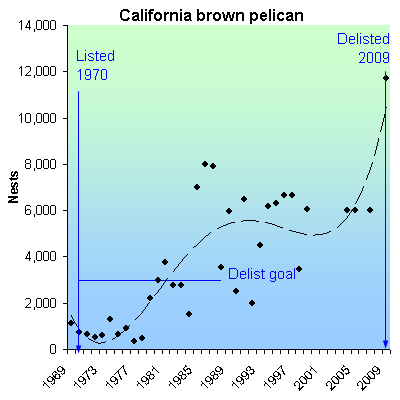

California brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus )

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 2/3/1983 |

Range: AZ(o), CA(b), OR(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

The California brown pelican declined due to habitat loss, reproductive failure from DDT-related eggshell thinning and toxic exposure to the pesticide endrin. It was listed as endangered in 1970, but continued declining to a low of 466 pairs in 1978. Since then, it as increased, though inconsistently, reaching 11,695 nesting pairs when delisted in 2009. The banning of DDT and protection of nesting areas, especially in Channel Islands National Park, are responsible for its recovery.

RECOVERY TREND

The California brown pelican’s (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) breeding range extends from California's Channel Islands south along the Pacific coast to Baja California, eastward throughout most of the Gulf of California, and southward along the mainland Pacific coast of Mexico to Islas Tres Maria [1]. It formerly bred as far north as Point Lobos in Monterey County. Currently, U.S. nesting colonies are located on West Anacapa and Santa Barbara islands of the California Channel Islands. The nesting range recently expanded to the Salton Sea [1]. As non-breeders, pelicans occur from southern British Columbia to El Salvador and inland in the U.S. to Southern California and Arizona.

The California nesting population declined from 1,125 to 727 annual nests between 1969 and 1970 when the species was placed on the list of endangered species [1]. The primary cause of decline was exposure to the pesticides endrin, which caused pelican mortality, and DDT, which caused egg-shell thinning. The Channel Island population was particularly impacted by a single Los Angeles factory which began discharging 200 to 500 kilograms of DDT daily in 1952.

DDT was banned in 1972, in large part because of the endangered species listing of the pelican, bald eagle and peregrine falcon. Following the ban, the pelican’s reproductive success began to improve quickly, although breeding effort did not show significant improvement until the early 1980s [3]. With the exception of a good year in 1974, the number of nests remained at low levels through 1978 when a low of 466 nests was recorded. Between 1979 and 1987, the population rose rapidly to 7,900 nests. Between 1987 and 2004, the number of nests fluctuated around a mean of about 5,000 nests. The 2004 nest count was about 7,500 (6,000 on West Anacapa and 1,500 on Santa Barbara Island). The 2006 nest count was about 9,000 with nesting on all three Anacapa islands (4,000 to 5,000), Santa Barbara Island (4,000) and Prince Island (43) [5]. 2006 was the first year since monitoring began that breeding occurred on all three Anacapa islands and the first time since 1939 that breeding occurred on Prince Island. In 1996, a small population of pelicans began nesting in the Salton Sea and has been present in most years since.

The California brown pelican was delisted in 2009 due to recovery, at which time there were 11,695 nesting pairs [7].

CITATIONS

[1] Shields, M. 2002. Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 609 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[2] Rogers, T. 2004. Spate of juvenile deaths follows breeding success. San Diego Union Tribune, August 1, 2004.

[3] Harrison, S.C. 2005. Petition to Delist the California Brown Pelican From the Listed of Endangered or Threatened Species Under the Endangered Species Act. Hunton & Williams, Washington, D.C., December 14, 2005.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. 90-Day Finding on a Petition to Delist the California Brown Pelican and Initiation of a 5-Year Review for the Brown Pelican. Federal Register, May 24, 2006 (71 FR 29908-29910).

[5] Broddrick, L.R. 2006. October 6, 2006 memorandum from L. Ryan Broddrick, Director, California Department of Fish and Game to John Carlson, Jr., Executive Director, California Fish and Game Commission, "Subject: Request of Endangered Species Recovery Council to delist the California brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) under the California Endangered Species Act."

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. 5-Year Review of the Listed Distinct Population Segment of the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). Albuquerque, NM.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Removal of the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, November 17, 2009 (74 FR 59444-59472).

California condor (Gymnogyps californianus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/24/1976 | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 4/25/1996 |

Range: AZ(b), CA(b) --- NV(x), OR(x), UT(x), WA(x)

SUMMARY

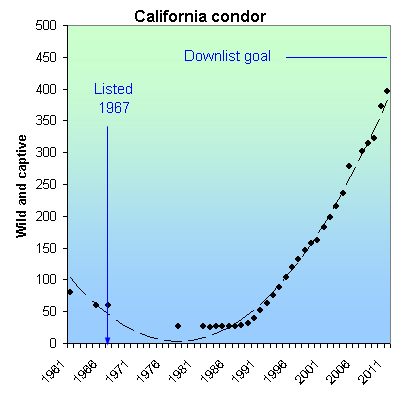

The California condor was nearly driven extinct by DDT, lead poisoning from ingested bullet fragments, and hunting. Lead poisoning remains a major threat to the species. Wild condors declined to nine birds by 1985. A captive-breeding and release program has increased the population to 386 birds as of 2012, including 213 wild and 173 captive birds.

RECOVERY TREND

The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) is a member of the vulture family and one of the largest flying birds in the world [1]. Ten-thousand years ago, its range extended across most of North America, but by the arrival of Europeans, its range was largely restricted to the Pacific Coast from British Columbia south to Baja California. By 1940, it was found only in the coastal mountains of Southern California where it nested in the rugged mountains and scavenged in the foothills and grasslands of the San Joaquin Valley. It was listed as an endangered species in 1967 and was given critical habitat the same year.

The condor's decline was driven by DDT which compromised reproduction, poisoning fromlead poisoning, shooting, collection, and drowning in uncovered oil sumps [1].

About 600 birds remained in 1890 [1, 2, 3]. It declined to about 60 birds in the late 1930s and early 1940s, 40 in the early 1960s, 27 in 1978, and nine in 1985. All remaining wild birds were taken into captivity in 1987. Since then, a successful captive breeding and reintroduction program increased the 2005 wild population to 121 and the captive population to 158 [2, 3].

The California Department of Fish and Game reports 302 condors in 2007; 315 in 2008; 322 in 2009; 373 in 2010; and 396 in 2011 [4].

The California condor now occurs in three wild populations: in mountains north of the Los Angeles basin, in the Big Sur area of the central California coast, and near the Grand Canyon in Arizona [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. California Condor Recovery Plan, Third Revision. Portland, Oregon. 62 pp.

[2] California Department of Fish and Game. 2005. California condor population size and distribution. Available at: http://www.dfg.ca.gov/hcpb/species/t_e_spp/tebird/Condor%20Pop%20Stat.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Condor population history. Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Available at: http://www.fws.gov/hoppermountain/cacondor/Pophistory.html.

[4] Ventana Wildlife Society. 2012. California Condor Recovery Program, Population Size and Distribution updates. Available at: http://www.ventanaws.org/pdf/Status_Reports/2012/Status_Report_February_2012.pdf.

California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/2001 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

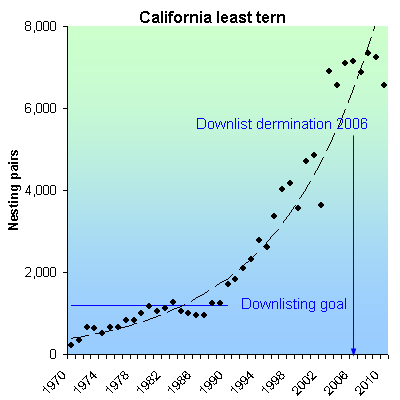

California least tern populations crashed in the late 19th century due to collection by the millinery trade. 20th century declines were driven by development, recreational crowding at beaches, and anthropogenically-exacerbated predation by wildlife. By 1970 when the tern was listed as endangered, just 225 pairs remained. Intensive habitat protection, predator control, and recreation management increased the tern to its overall delisting goal of 1,200 pairs in 1988 and to 6,568 pairs in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The California least tern (Sterna antillarum browni) nests in colonies on the Pacific coast of California and Baja, Mexico on relatively open beaches where vegetation is limited by tidal scouring [1]. It was formerly found in great abundance from Moss Landing, Monterey County, Calif. to San Jose del Cabo, southern Baja California, Mexico. It declined in the 19th and early 20th centuries due to the millinery trade that hunted birds for their feathers for women's hats, but to a lesser degree than many East Coast birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1916 ended the threat, but the least tern plummeted again some decades later due to growing development and recreational pressures that destroyed habitat, disturbed birds, and increased predation by introduced and native species. The construction of the Pacific Coast Highway brought all these threats to much of California's coast. By the 1940s, terns were extirpated from most beaches of Orange and Los Angeles counties and were considered sparse elsewhere. To avoid humans, some tern colonies nest at inland mudflat and dredge fill sites, which appears to make them more susceptible to predation by foxes, raccoons, cats and dogs.

When placed on the endangered species list in 1970, just 225 nesting tern pairs were recorded in California [2]. Protection of nest beaches from development and disturbance, and active predator control programs allowed the species to steadily increase to about 7,100 pairs in California in 2004 [2, 5]. A portion of the increase in the 1970s is attributable to expansion and greater consistency in survey effort, but the greatest increases occurred from 1980 to the present. In 2004, 57 percent of nesting pairs occurred in San Diego County, 26 percent in Los Angeles and Orange counties, 10 percent in Ventura County, 1 percent in San Louis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties, and 6 percent in the San Francisco Bay [3]; the largest sites were at Camp Pendleton (21 percent), U.S. Navy lands at San Diego Bay (16 percent), Los Angeles Harbor, Pier 400 (15 percent), Point Mugu (8 percent), Alameda Point (6 percent), Batiquitos Lagoon Ecological Reserve (6 percent), Huntington State Beach (5 percent), and Tijuana Estuary (5 percent). Since 2005, the population has remained relatively static at about 7,000 pairs. In 2010 there were 6,568 pairs [8,9].

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan for the California least tern was issued in 1980 and revised in 1985 [1]. Its downlisting and delisting criteria incorporate the total population size, number of colonies, geographic distribution, population viability, and management status. To be downlisted to "threatened" status, the tern must have at least 1,200 breeding pairs distributed in at least 15 "secure" management areas. Each of these management areas must have at least one viable colony. The San Francisco Bay, Mission Bay and San Diego Bay management areas must have at least three, five, and four viable colonies respectively. To be viable, a colony must have at least 20 breeding pairs, a three-year mean reproduction rate of >= 1.0 fledglings/pair, and be fully protected under a long-term management plan. This would require a minimum of 24 viable colonies. To be recovered and delisted, the tern must have at least 1,200 breeding pairs distributed in at least 20 "secure" management areas. Each of these management areas must have at least one viable colony with a mean five-year reproduction rate of >= 1.0 fledglings/pair. The San Francisco Bay, Mission Bay and San Diego Bay management areas must have at least four, six, and six viable colonies respectively. This would require a minimum of 33 viable colonies.

The total population size of 1,200 breeding pairs for downlisting and delisting was reached in 1988 and all subsequent years. The downlisting criterion of 24 colonies was met in 1996 and all subsequent years. The delisting criterion of 33 colonies was met in 2003 and 2004. However, neither the downlisting nor delisting requirements for distribution and viability have been met. While human disturbance has been managed with fencing at most nesting areas, protection from native and non-native predators will require permanent management commitments to ensure continuing viability after the species is recovered and delisted [3].

In 2006, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a five-year review recommending the downlisting of the California least tern [5]. It acknowledged that all the downlisting criteria had not been achieved, but asserted that the recovery criteria were out of date. The downlisting recommendation was opposed by the Service biologist who prepared the five-year review [6].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Recovery Plan for the California Least Tern, Sterna Antillarum Browni. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. 112pg.

[2] Keane, K. 2005. California least tern monitoring 1969-2004. Spreadsheet provided by Kathy Keene, Keane Biological Consulting, Long Beach, CA on July 25, 2005.

[3] Keane Biological Consulting. 2004. Breeding Biology of the California Least Tern in the Los Angeles Harbor, 2004 Breeding Season. Prepared for the Port of Los Angeles, Environmental Management Division, under contract with the Port of Los Angeles, Agreement No. 2316.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Draft revised recovery plan for the California least tern. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carlsbad, CA.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. California least tern (Sterna antillarum browni) 5-year review summary and evaluation. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carlsbad, CA.

[6] Pagel, J. 2006. Letter from Joel Pagel, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to Scott Sobiech, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, dated August 23, 2006.

[7] Suckling, K. 2007. Personal observation, Kieran Suckling, Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ, October 1, 2007.

[8] Keane, K, N. Mudry and S. Langdon. 2011. Status Of The Endangered California Least Tern: Population Trends And Indicators For The Future. Presentation to the Least Tern Working Group annual meeting January 7, 2011.

[9] Marschalek, D. 2011. California Least Tern Breeding Survey 2010 Season. Available online at http://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentVersionID=59326, accessed September 13, 2011.

El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides allyni)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/1/1976 | Recovery plan: 9/28/1998 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

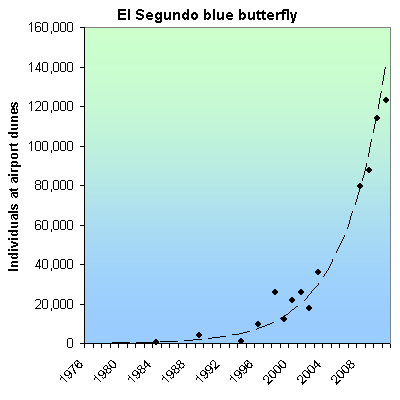

The El Segundo blue butterfly lost approximately 90 percent of its oceanside habitat to construction of the Los Angeles Airport and a housing development. The remaining habitat was highly degraded and overtaken by exotic plants that crowded out its host. The butterfly declined from about 1,000 individuals in the late 1970s, when listed as an endangered species, to about 500 in 1984 before being saved by restoration efforts that steadily increased the population at the Airport Dunes to 123,000 in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides ailyni) formerly extended over much of the 3,200-acre El Segundo Dunes of Los Angeles County, Calif. The dunes ranged from Ocean Beach (near Santa Monica) south to Magala Cove in Palos Verdes and were bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and the east by Los Angeles coastal prairie.

The El Segundo blue occupied areas within the dunes with high sand content and its obligate host plant, coast buckwheat (Eriogonum parvifolium). The historic population size likely averaged 750,000 butterflies per year [2]. The prairie has since been entirely converted to an urban landscape and the dunes reduced to about 307 mostly degraded acres. The extent of habitat loss peaked, and El Segundo blue numbers likely reached their nadir, in the late 1970s, when virtually all of the dunes were developed or degraded.

Restoration efforts were initiated in the 1980s. Virtually all remaining potential habitat was protected from private development due to geological, conservation and other restrictions by 1990 and was believed to be capable of supporting 100,000 butterflies if fully restored [2]. However, governmental development, especially by the city of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Airport (LAX) is still a significant threat [4].

AIRPORT DUNES

To end a long conflict with its neighbors, LAX condemned and removed 822 homes from 200 acres on its western border between 1966 and 1975 [2]. The airport has alternately sought to restore and destroy El Segundo blue habitat on the site. In 1975, about 70 percent of the back dune was excavated and recaptured to realign Pershing Drive [2]. The area was reseeded with California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), which attracted competing nonnative moths and butterflies, suppressing El Segundo blue numbers. The foredune to the south and west, and last fragment of coastal prairie, were graded during this same period. Only about 40 of the 200 acres escaped degradation during the 1970s. The impacts extirpated 17 of 20 native mammals, seven of 31 butterfly species, seven of 18 amphibians and reptiles, and all five coastal scrub obligate birds [2]. Twenty-two of 73 native species present in 1940 were absent in 1989 and 19 of 51 of extant native plants were represented by fewer than 100 individuals [1].

The El Segundo blue was placed on the federal endangered species list in 1976. LAX proposed developing the dunes as a recreational site with a 27-hole golf course and a 92-acre butterfly preserve in 1982 [2]. In 1985 the California Coastal Commission refused to issue a permit for the project. In the late 1990s, LAX proposed to extend runway into the dunes [1]. In 1987 the city of Los Angeles initiated efforts to reduce California buckwheat and increase coast buckwheat populations. In 1992, the city of Los Angeles established a 203-acre Habitat Restoration Area within the dunes. In response, the population rose from approximately 400-700 in 1984 to about 123,000 in 2011 in response to the habitat restoration actions [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7].

CHEVRON BUTTERFLY PRESERE

The 1.6-acre Chevron butterfly preserve has been isolated by development since the 1950s [1]. It is estimated to have supported about 2,000 butterflies from 1965 to 1976 [2]. The population dropped to 1,600 in 1977, 681 in 1979, 400 in 1986 [2]. The decline may have been caused by dune stabilization or lepidopterists crisscrossing the small site, using a capture-release method that can harm butterflies, and removing 839 butterfly larvae for study [2]. In 1986, the preserve had 240 host plants and 1,000 introduced seedlings [2]. The 1996 population was estimated at 5,000 to 7,000 butterflies on 1,200 host plants [1]. The population increase has been attributed to intensive management for the El Segundo blue [1].

MALAGA COVE

The El Segundo blue population was discovered on an eroded and iceplant dominated site in Malaga Cove in 1983 [2]. It had 60 butterflies and fewer than 50 host plants on 1 acre in 1984 [2]. It was fenced in 1986 [2]. Host plants and butterfly populations in 1990 were similar to the 1984 count [2]. The site was degraded by illegal dumping in 1997 [1]. In 2004 it supported 10-30 butterflies [3]. An adjacent population was discovered in 2000 in coastal bluff scrub habitat at York Long Point [3].

BALLON WETLANDS

A single male was reported but not captured at a potentially suitable six-acre private land site within Ballona Wetlands in 1985 [2]. Fifteen host plants but no butterflies were found there on a small dune fragment in 1986 [2]. By 1989 half the plants were dead [2]. A seven-acre site was seeded with native plants in 1990 but was significantly disturbed by a lagoon restoration project in 1997 [1]. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a permit to reintroduce the species prior to 1990, but the program has not been carried out [2].

HYPERION

A single butterfly was observed in the late 1980s near a remnant dune on a 30-acre site east of the Hyperion sewage treatment plan [1]. The site was extensively planted with exotic vegetation in 1995 by the cities of El Segundo and Los Angeles [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. El Segundo Blue (Euphilotes battoides allyni) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

[2] Mattoni, R. 1990. The endangered El Segundo blue butterfly. Journal of Research on the Leptidoptera 29(4):277-304.

[3] Mattoni, R., T. Longcore, C. Zonneveld and V. Novotny. 2001. Analysis of transect counts to monitor population size in endangered insects: the case of the El Segundo blue butterfly, Euphilotes battoides allyni. Journal of Insect Conservation 5:197-206.

[4] Rich, C. 2003. Letter from Catherine Rich, Executive Director, The Urban Wildlands Group, to Cindy Miscikowski, Los Angeles Councilwoman, August 4, 2003.

[5] Los Angeles World Airports. 2012. LAX’s 2011 El Segundo blue butterfly population count increases eight percent over previous year. Press release available at http://www.lawa.org/newsContent.aspx?ID=1547

[6] Sapphos Environmental, Inc. 2005. LAX Master Plan Final EIS, Appendix A-3c: Los Angeles/El Segundo Dunes Habitat Restoration Plan. Los Angeles World Airports, U.S. Department of Transportation, and Federal Aviation Administration.

[7] Los Angeles World Airports. 2011. LAX’s El Segundo blue butterfly count increases thirty percent over 2009. Press release available at http://vny.aero/newsContent.aspx?ID=1394 [8] Marroquin, A. 2009. Once-endangered El Segundo blue butterfly now thrives. DailyBreeze.com July 29. 2009. Available at http://news.duneguide.com/2009_07_01_archive.html

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 7/30/2010 |

Range: AL(o), AK(s), CA(s), CT(s), DE(s), FL(s), GA(s), HI(s), LA(o), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(o), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), OR(s), PA(s), RI(s), SC(s), TX(o), VA(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

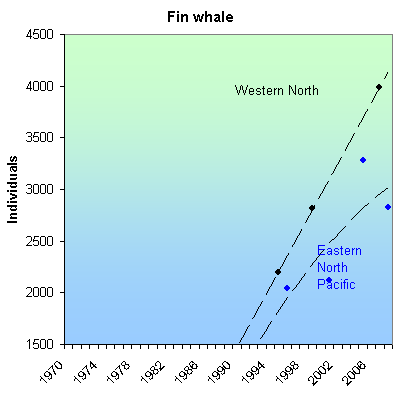

Fin whales were hunted in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century, causing population decline. Ongoing threats include illegal and legal whaling, vessel collisions, fishing gear entanglement, reduced prey and noise. Total population size is unknown, but both the North Atlantic and North Pacific populations increased between 1995 and 2009.

RECOVERY TREND

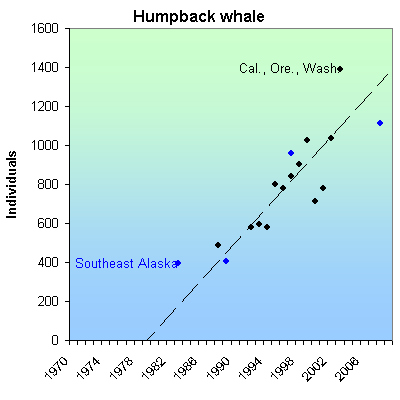

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and southern oceans mix rarely, if at all. For management purposes, the North Pacific is divided into three stocks: 1) the California/Oregon/Washington stock, 2) the Hawaii stock and 3) the Alaska stock [2]. A western North Atlantic stock inhabits U.S. waters along northeastern coasts [3]. Most groups are thought to migrate seasonally, in some cases over large distances [1]. They feed at high latitudes in summer and move to low latitudes in winter. Some groups move over shorter distances and may be resident to areas with a year-round supply of adequate prey.

Fin whales were hunted, often intensively, in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century [1]. From 1947 to 1987, approximately 46,000 fin whales were taken from the North Pacific [2]. Commercial whaling did not end until 1976 in the North Pacific and 1987 in the North Atlantic. The current status of fin whale populations relative to pre-whaling levels is uncertain.

In the North Pacific, pre-whaling populations were estimated to be between 42,000 and 45,000 [2]. By 1973, the North Pacific population is thought to have been reduced to 13,620-18,680 — less than 38 percent of historic carrying capacity [2].

California/Oregon/Washington Stock

The California/Oregon/Washington stock of the North Pacific is thought to be increasing [5]. Fin whale acoustic signals are detected year-round off Northern California, Oregon and Washington, with a concentration of vocal activity between September and February [2]. Fin whales increased in abundance along the California coast between 1979 and 1996, and based on ship surveys in 2001, they continued to increase. Populations appeared to be increasing monotonically from 1991 to 2001 [5]. In 2001, 3,279 (CV= 0.31) were estimated in California, Oregon and Washington coastal waters [2]. The 2008 population was estimated at 2,825 whales [9].

Alaskan Stock

Since 1999, information on abundance of fin whales in Alaskan waters has improved and although the full range has not yet been surveyed, a rough estimate of the size of the population west of the Kenai Peninsula is 5,703 [6]. Surveys conducted in 1999 and 2000 in the central-eastern Bering Sea and southeastern Bering Sea provided provisional estimates of 3,368 (CV = 0.29) and 683 (CV = 0.32), respectively [6]. One aggregation of fin whales spotted in 1999 involved more than 100 animals [6]. Because historical abundance information is lacking, population trends are difficult to determine [6].

Hawaiian Stock

Fin whales are rare in Hawaiian waters and the stock is thought to be quite small [7]. Over the course of 12 aerial surveys conducted within about 25 nautical miles of the main Hawaiian Islands in 1993-98, only one fin whale was sighted [7]. More recent acoustic data suggest that fin whales migrate into Hawaiian waters mainly in fall and winter [7]. In 2002, a ship survey of the entire Hawaiian Islands resulted in an abundance estimate of 174 (CV=0.72) fin whales [7].

Western North Atlantic Population

Western North Atlantic fin whales off the eastern U.S. coast north to Nova Scotia and the southeastern coast of Newfoundland are considered a single stock [3]. New England waters represent a major feeding ground, and calving is thought to take place along mid-Atlantic U.S. latitudes from October to January. The locations used for calving, mating and wintering for most of the population remains unknown. It is likely that fin whales occurring in the U.S. Atlantic undergo migrations into Canadian waters, open-ocean areas, and perhaps even subtropical or tropical regions. An abundance of 2,200 (CV=0.24) fin whales was estimated from a 1995 line-transect sighting survey that covered waters from Virginia to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. A 1999 estimate of 2,814 (CV=0.21) fin whales, currently considered the best estimate for the western North Atlantic stock, was derived from a line-transect sighting covering waters from Georges Bank to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence [3]. The best estimate of population for this stock in 2007 is 3,985 whales [8]. Although there is little data on population trends, the minimum population estimate reported in NOAA Fisheries Stock Assessment Reports has steadily increased since 1992.

The main direct threat to fin whales today is the possibility of illegal whaling or a resumption of legal whaling [1]. In 2006, Japan announced that it would expand hunts to include fin whales [4]. It expected to harvest 10 fin whales from Antarctic waters [4]. Collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced prey abundance due to overfishing and habitat degradation, as well as disturbance from low frequency noise, are also potential threats [1]. The offshore drift gillnet fishery is the main fishery likely to take fin whales [2].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1998. Draft Recovery Plan for the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Sei Whale (Balaenoptera Borealis). Silver Spring, MD.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis): Western Stock revised Dec., 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic stock. Revised Dec. 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[4] Hans Greimel, Associated Press. 2005. Japan To Double Usual Whale Kill in New Antarctic Hunt, Expanded To Include Fin Whales. Nov. 9, 2005.

[5] Barlow, J. 2003. Preliminary Estimates of the Abundance of Cetaceans along the U.S. West Coast: 1991-2001 Southwest Fisheries Science Center Administrative Report LJ-03-03. Available at <http://swfsc.nmfs.noaa.gov/prd/PROGRAMS/CMMP/default.htm>.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Northeast Pacific stock. Revised 10/21/2004.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Draft Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Hawaiian stock. Revised 3/15/2005.

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised 11/2010.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2011. 2010 Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): California/Oregon/Washington stock. Revised 1/15/2011.

Gray whale (Eastern North Pacific DPS) (Eschrichtius robustus pop. 3)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: AK(b), CA(b), OR(b), WA(b) ---

SUMMARY

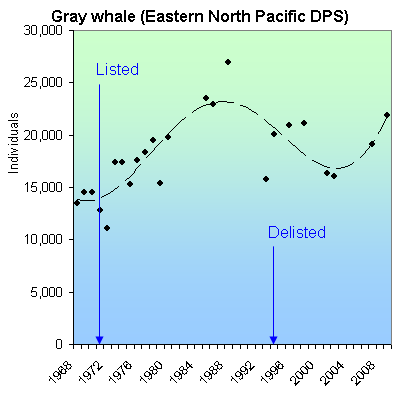

Gray whales declined precipitously due to whaling, becoming extinct in the Atlantic, endangered in the Eastern North Pacific and extremely endangered in the Western North Pacific. They are threatened by oil and gas drilling and coastal development. In 1968, there were 13,426 Eastern North Pacific gray whales. The species was was listed as endangered in 1970 and removed from the list in 1994 when the population reached 20,103 whales. The 2009 population was estimated to be 21,911.

RECOVERY TREND

The Eastern North Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) migrates along the West Coast from summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi seas to nearly landlocked lagoons and bays along the west coast of Baja California where calves are born from early January to mid-February [2].

It historic population size has been estimated at about 19,500 [1] based on log books and historical accounts [4]. However, recent genetic analysis indicates a historic population on the order of 96,000 whales (76,000–118,000) [3].

Early indigenous whaling impacts were likely substantial to this near-shore species, especially to resident populations [4], but have not been quantified. The added pressure of commercial whaling however, drove the species to near extinction in the 19th and 20th centuries. Between 1846 and 1900, commercial whalers killed nearly 9,000 gray whales and indigenous hunters about 6,000 [1]. After 1900, the two groups killed another 11,500 whales, for a total of 27,000 between 1846 and 1946.

Commercial whaling was prohibited in 1946 and indigenous whaling was greatly reduced. At the time of its listing as an endangered species in 1970, the gray whale was extinct in the Atlantic, at low levels in the Eastern North Pacific, and at extremely low levels in the Western North Pacific [2].

Between 1968 and 1988, the Eastern North Pacific gray whale grew from 13,426 whales to a post-exploitation peak of 26,916 [1]. It declined to 20,103 whales by 1994 when it was delisted, remained stable for a few years, and then declined again to about 16,000 whales in 2001 and 2002. These declines were preceded by an unprecedented number of whale strandings in 1999 (273) and 2000 (355), greatly exceeding the previous average (38). The stranding were also unusual in being dominated by adults and subadults (>60%) rather than calves. The whales were visibly emaciated, possibly due to poor feeding conditions (i.e. extensive ice cover) in their wintering grounds.

Recent population estimate are in dispute. The 2010 reanalysis cited for all population numbers in this account [1], indicates the stock grew to 21,911 whales in 2009.

The Western North Pacific gray whale remains listed as an endangered foreign species. It has not recovered since listing and today is comprised of less than 100 whales which are highly endangered by oil and gas drilling proposals in Asia and Russia.

CITATIONS

[1] Punt, A.E. and P.R. Wade. 2010. Population Status of the Eastern North Pacific Stock of Gray Whales in 2009. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-207, 43 p.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1994 Final Rule to Remove the Eastern North Pacific Population of the Gray Whale From the List of Endangered Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 31094.

[3] Alter, S.E., E. Rynes and S.R. Palumbi. 2007. DNA evidence for historical population size and past ecological impacts of gray whales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:15162–15167.

[4] Pyenson, N.D. and D.R. Lindberg. 2011. What Happened to Gray Whales during the Pleistocene? The Ecological Impact of Sea-Level Change on Benthic Feeding Areas in the North Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE 6(7): e21295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021295.

Gray wolf (Northern Rockies DPS) (Canis lupus (Northern Rockies DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 8/3/1987 |

Range: ID(b), MT(b), eastern OR(b), eastern WA(b), WY(b), northern UT(o)

SUMMARY

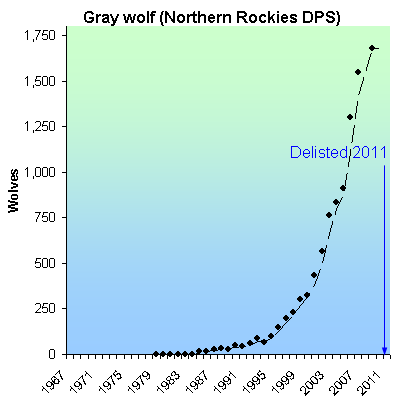

Gray wolves were purposefully hunted, trapped and poisoned to near extinction in the western United States, often by the federal government or with the encouragement of private and state bounties. By 1973, no wild wolves remained in the region. They were listed as endangered in 1967 and began recolonizing the Northern Rocky Mountains from Canada in the early 1980s. Due to prohibition of killing, habitat protection, and reintroductions, the population grew rapidly, was downlisted in 2003, reached 1,679 wolves by 2009, and was delisted in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The Northern Rocky Mountains gray wolf (Canis lupus pop.) historically occurred throughout Idaho, the eastern third of Washington and Oregon, all but the northeastern third of Montana, the northern two-thirds of Wyoming, and the Black Hills of South Dakota [1]. As early American settlers began moving west, populations of the gray wolf’s important prey species were over-hunted, causing the wolves to resort to hunting sheep and cattle. As a result, bounty hunting of wolves began in the 19th century and continued through as late as 1965. Around the turn of the century some population control measures were attempted in Yellowstone National Park that led to increased numbers of gray wolves in the area. In response, however, people began killing large numbers of wolves [1]. Beginning in 1912 a minimum of 136 wolves and 80 pups were killed each year and by 1920, only 30 to 40 wolves persisted in this area [1]. By 1973, gray wolves were exterminated from the western lower 48 states and existed only in northeastern Minnesota and Isle Royal, Mich. [2].

Protection of gray wolves was not initiated until the enactment of the Endangered Species Act. By this time gray wolves no longer occurred in the western United States except for the occasional dispersion of Canadian animals into Montana and Idaho that failed to survive long enough to reproduce [3]. Successful recolonization of gray wolves into the Rocky Mountain region did not occur until the early 1980s. Around this time, the Rocky Mountain Gray Wolf Recovery Team was organized with the intent of developing standard observation methods for studying and monitoring the wolves. In 1987, a recovery plan was published. Around this time, the status of the Rocky Mountain Gray wolf was still quite precarious. In Montana, from 1985 to 1986 roughly 15 to 20 wolves were believed to occur near Glacier National Park. In Wyoming from 1982 to 1985, 15 wolves were reported at Yellowstone National Park, and the same number were believed to occur in Idaho in 1986 [1].

Regular monitoring of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf population did not occur until 1995, at which time there were an estimated 14 wolves in Montana and 15 in greater Yellowstone. By 2000, there were an estimated 65 wolves in Montana, 118 in Yellowstone, and 141 in central Idaho [4]. In 2004, a recovery update of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf was released, providing information regarding the status of the gray wolf at three designated recovery areas: the Northwestern Montana Recovery Area (NWMT) in Montana and the Northern Idaho panhandle; the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA), which includes Wyoming and adjacent parts of Idaho and Montana; and the Central Idaho (CID) area covering central Idaho and adjacent parts of southwest Montana. As of 2004, 16 packs containing 59 wolves were documented at NWMT [3]. In the GYA, 171 wolves in 16 packs inhabited the Wyoming portion and 17 packs occurred in the Montana region. In the CID 64 wolves in 40 groups and as individuals were monitored [3]. The total population of free ranging Rocky Mountain Gray wolves for 2004 was estimated at 59 in Montana, 324 in Greater Yellowstone, and 422 in Central Idaho. In 2005 population estimates were 93, 294, and 525 respectively [4]. In 2009 the population of wolves in the Northern Rockies was about 1,679, up from 1,545 in 2007 and 1,300 in 2006 [4].

The U.S. Fish and Wildife Service delisted the Northern Rockies gray wolf in 2008, but the decision was objected to by conservationists who argued that the recovery plan goal was outdated, and insufficient to remove the threat of extinction because it did not require a large enough or well-connected enough wolf meta-population. In 2011, with encouragement from the Department of Interior, Congress for the first time in the history of the Endangered Species Act, overruled the courts and order the delisting of the Northern Rockies gray wolf without biological or legal review [7].

CITATIONS

[1] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1987. Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Denver, CO. 119pp

[2] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Gray Wolf. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Revised May, 2004.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nez Perce Tribe, National Park Service, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Idaho Fish and Game, and USDA Wildlife Services. 2005. Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Helena, MT. 72pp. Available at <http://westerngraywolf.fws.gov/annualreports.htm>

[4] International Wolf Center. 2011. Gray Wolf Population Trends in the Contiguous United States. Website <http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/wow/regions/United_States_Subpages/Biology1.asp> Accessed October 6, 2011..

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Designating the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment; Removing the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment of Gray Wolf From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, February 8, 2006 (71 FR 6634-6660).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data cited by Brad Knickerbocker, Gray wolves may lose US protected status, Christian Science Monitor, Febraury 1, 2007.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Reissuance of Final Rule To Identify the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment and To Revise the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 76 Fed. Reg. 26086.

Guadalupe fur seal (Arctocephalus townsendi)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 12/16/1985 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

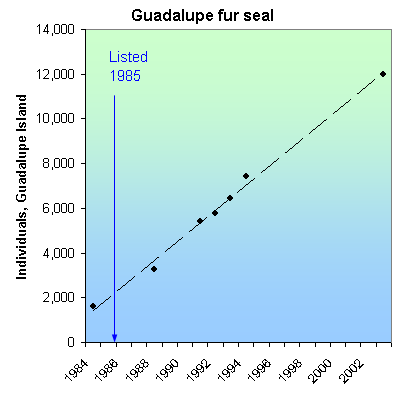

The Guadalupe fur seal was largely extirpated from California in the 1800's due to hunting; it was thought extinct until a bull was seen on San Nicholas Island, California in 1949, and 14 seals were found on Guadalupe in 1954. Since listing, seals have recolonized the U.S. and have been seen in the Channel and Farallon Islands with increasing regularity since the 1980s. The population on Guadalupe Island increased from 1,600 in 1984 to 12,000 in 2003.

RECOVERY TREND