Atlantic green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas mydas)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(s), DE(m), FL(b), GA(b), LA(s), MA(s), MS(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), TX(s), VI(b), VA(m) ---

SUMMARY

The Atlantic green sea is threatened by egg collection, hunting, vandalism, disturbance while nesting, beach development, habitat loss, and sea level rise. Its population has increased in the United States since being listed as endangered in 1978, but systematic surveys only began in 1989. It grew by 2,206% in Florida between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) and has achieved its population size recovery goal.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 2]. It migrates enormous distances between foraging and nesting areas [2]. When not migrating, the green sea turtle’s typical near-shore habitat includes shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets [1]. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches [3]. Females generally breed every two or more years, and nest an average of three to four times per breeding year [4].

Exploitation of the green sea turtle, its eggs and its habitat resulted in population declines [1]. Although green sea turtle populations continue to decline throughout much of their range due to directed harvest (both illegal and legal), incidental capture in near-shore gillnets, and negative impacts on essential habitats [1], two populations that nest in the United States (Florida and Hawaii) have increased in size since the species was placed on the endangered list in 1978 [3].

Green sea turtle populations in the U.S. Atlantic occur from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean [1, 2]. In the U.S. Pacific, green sea turtles occur from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 2]. Atlantic green sea turtles are variously considered a population and a subspecies (Chelonia mydas mydas) [1]. In the U.S. Atlantic, nesting occurs primarily on beaches along Florida’s east coast, although smaller numbers of nests can be found in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico [5]. Foraging occurs in the Gulf of Mexico to Texas and along the Atlantic Coast to Massachusetts [1].

CARIBBEAN

Reliable, long-term nesting data are unavailable for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands [8]. The number of green turtle nests has remained low for all the islands, but there appears to have been a gradual increase in the numbers of juveniles observed in foraging grounds since the mid-1970s [8]. The largest concentration of nests occurs on St. Croix, where an average of 100 were counted per year between 1980 and 1990. Waters surrounding the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico have been designated critical habitat [1].

FLORIDA

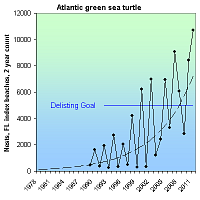

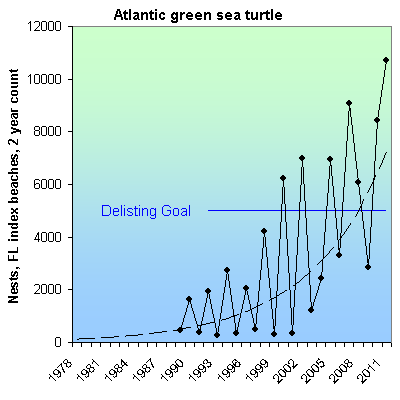

State-wide population counts have been conducted in Florida since the 1970s, but are not strictly controlled for survey effort and area, especially in the early years. Thus while it is known that Florida's nesting green sea turtle population has increased since the 1970s, it is not possible to determine by how much. Standardized surveys on a large number of "index beaches" was initiated in 1989. They demonstrate that the number of annual green sea turtle nests increased by 2,206% between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) [4].

The number of green sea turtle nests in Florida (and in many other places), generally alternates between high and low years. Between 1989 and 2001, the number of nests in low years remained flat (250-500). Between 2003 and 2011 it grew sharply. Nesting in high years grew throughout 1989-2011, but more sharply starting in 1998.

An unusually low count in 2004 was caused by a hurricane. The biennial cycle was broken in 2009 and 2011, resulting in the highest recorded count in what should have been a low year (2011 = 10,701). It is possible to predict at this point if 2012 will be a high or low year.

NORTHERN STATES

Each winter green, Kemps Ridley and loggerhead sea turtles migrating southward from northeastern waters are regularly stranded on shores of Cape Cod Bay between Brewster and Truro [7]. These turtles die of hypothermia if not rescued. The total number of strandings ranged between 49 and 281 turtles between 1995 and 2003. Green sea turtle strandings ranged from zero to seven each year [7]. A volunteer program has been established to rescue, rehabilitate and release the turtles in Florida.

In 2005, the first verified green sea turtle nest was found in Virginia. A few females previously had laid eggs on beaches as far north as North Carolina's Outer Banks [10].

RECOVERY PLAN

In order for the green sea turtle to be delisted, the 1991 federal recovery plan requires that Florida supports an average of 5,000 nests over six consecutive years [1]. This criterion was met in 2009, 2010, and 2011 on the index beaches. As these are a subset of all nesting beaches, the delisting criteria was met in at least all years between 2007 and 2011.

The recovery plan also requires that 2) at least 105 kilometers of nesting beach be in public ownership and support at least 50 percent of U.S. nests, and 3) a reduction in stage-class mortality results in an increase in individuals in foraging grounds [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. Washington, DC.

[2] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Silver Spring, Maryland.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Office. Website (http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/Green-Sea-Turtle.htm) accessed January, 2006.

[4] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available at (http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/, accessed May, 2012).

[5] National Marine Fisheries Service. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). Threatened Species Account. Endangered Florida and Mexican Breeding Populations. NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Silver Spring, MD. Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/green.html) accessed January, 2006.

[6] Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. 2006. Florida's index nesting beach survey data. Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission,. Website (http://research.myfwc.com/features/view_article.asp?id=10690) accessed January, 2006.

[7] Lewis, D. Photo diary of a terrapin researcher. Website (http://terrapindiary.org/) accessed January 7, 2006.

[8] Hillis-Starr, Z.M., R. Boulon, M. Evans. Sea turtles in the Virgin Islands in Status and trends of the Nation's Biological Resources, USGS. Available at (http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/cr136.htm, accessed January, 2006.)

[9] Orlando Sentinel. August 6, 2005. Green Sea Turtle makes odd egg-laying visit to Virginia. Page A20.

Atlantic hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(o), DE(o), FL(b), GA(o), LA(s), MD(o), MA(o), MS(s), NY(o), NJ(o), NC(o), PR(b), RI(o), SC(o), TX(s), VI(b), VA(o) ---

SUMMARY

Globally, the number of hawksbill sea turtles may have declined by as much as 80 percent over the past century due to commerce in their shells, poaching, habitat loss, bycatch and entanglement in marine debris. Although hawksbill numbers continue to decline globally, at protected beaches on Mona Island, Puerto Rico, nests increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

Hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricatause) use different habitats at different stages of their life cycle [1]. Post-hatchling hawksbills occupy pelagic environments, taking shelter in weedlines that accumulate at convergence zones [1]. They reenter coastal waters when they reach approximately 20 to 25 centimeters carapace length [1]. Coral reefs are used as resident foraging habitat by juveniles, subadults and adults [1]. Along the eastern shores of continents where coral reefs are absent, hawksbills are known to inhabit mangrove-fringed bays and estuaries [1]. They feed primarily on sponges [1, 2]. Female hawksbills nest on low- and high-energy beaches of tropical oceans. Throughout their range, hawksbills typically nest at low densities with aggregations consisting of a few dozen, or at most a few hundred individuals [1]. Nests have been found on both insular and mainland beaches where nests are typically placed under vegetation [1]. Migratory patterns of hawksbills are not well known, although a reproductive migration is thought to take place [1, 2].

Hawksbills occur in tropical and subtropical seas of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans and nest on beaches in at least 60 different nations [3]. Along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the continental U.S., hawksbills have been reported by all of the Gulf states and from as far north as Massachusetts, although sightings north of Florida are rare [1]. Representatives of at least some life-history stages regularly occur in southern Florida (where the warm Gulf Stream current passes close to shore) and the northern Gulf of Mexico (especially Texas), in the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and along the Central American mainland south to Brazil [1].

The largest remaining concentrations of nesting hawksbills occur on the beaches of remote oceanic islands of Australia and the Indian Ocean [1]. The Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico also supports a significant population of nesting hawksbills [1]. Within U.S. jurisdiction, nesting occurs principally on beaches in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The most important nesting sites are Mona Island (Puerto Rico) and Buck Island (St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands) [1]. Within the continental United States, nesting is restricted to the southeastern coast of Florida and the Florida Keys, where one or two nests have been reported annually [1].

Quantitative data on population changes of hawksbills are scarce, in part because hawksbills were already greatly reduced in number when scientific studies of sea turtles began in the late 1950s [3]. In addition, visual evidence of hawksbill nesting is the least obvious among the sea turtle species, because hawksbills often select remote pocket beaches with little exposed sand to leave traces of revealing crawl marks [1]. An estimate of the minimum number of female hawksbills in 1989 indicated that at least 15,000 to 25,000 female hawksbills nested annually worldwide [4]. Although global numbers are very difficult to estimate, it appears that this turtle has suffered drastic decline, probably by as much as 80 percent over the last century (3). Only five regional populations, Seychelles, Mexico, Indonesia, and two in Australia, support more than 1,000 nesting females annually [3]. Hawksbill populations are either known or suspected to be declining in 38 of the 65 geopolitical units for which nesting density estimates are available [3].

CARIBBEAN

Hawksbill populations in the Western Atlantic-Caribbean region are thought to be greatly depleted [3]. In the Caribbean region, the number of females nesting annually is about 5,000 (order-of-magnitude estimate) [3]. With few exceptions, all of the countries in the Caribbean report fewer than 100 females nesting annually [3]. The largest known nesting concentrations are in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico [3]. These populations may be increasing [3]. A total of 4,522 nests were recorded in the states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo in 1996, compared to only a few hundred in the early 1980s [5].

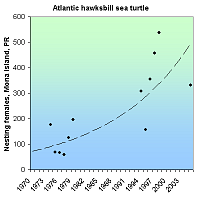

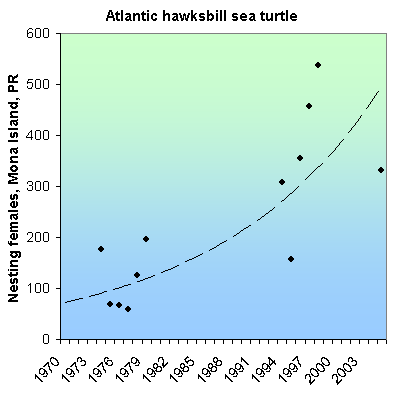

In the U.S Caribbean, there is evidence that hawksbill nesting populations have been severely reduced during the 20th century [1]. Estimates of the size of nesting populations under U.S. jurisdiction are available for only a few localities [1]. Although trends are uncertain due to long intervals between hawksbill nesting generations (hawksbill take between 30 and 40 years to reach sexual maturity) and fluctuations in the number of reproductive females that nest in a particular year [3], hawksbill numbers increased at two protected locations, Mona Island, Puerto Rico and at Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands [5]. The number of nests on Mona Island increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005 [5, 6]. On Buck Island, the number of nesting females increased from 73 in 1987 to 121 in 1998, and averaged 56 from 2001-2005 [5, 6].

International commerce in hawksbill shell (“tortoiseshell” or “bekko”) may be the most significant factor endangering hawksbill populations worldwide [1]. Despite protective legislation, international trade in tortoiseshell and subsistence use of meat and eggs continues in many countries [1]. Females and eggs are vulnerable to poaching on nesting beaches and nests are vulnerable to beach erosion [1]. Egg poaching is a serious problem in Puerto Rico and also occurs in the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The practice of beach armoring can prevent females from reaching suitable nesting sites and can result in the loss of dry nesting beaches [1, 2]. Many hawksbill nesting beaches in the Caribbean are privately owned and in jeopardy of being developed [1]. Sand mining is also a threat to nesting beaches throughout the Caribbean [1]. The extent to which hawksbills are killed or debilitated after becoming entangled in marine debris has not been quantified, but it is believed to be a serious and growing problem [1]. Incidental catch in finfish fisheries may also pose a serious threat and the ingestion of marine debris (i.e. plastic bags, styrofoam) can result in hawksbill mortality [1].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Recovery Plan for Hawksbill Turtles in the U.S. Caribbean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico. St. Petersburg, Florida.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Silver Spring, MD.

[3] Meylan, A.B. and M. Donnelly. 1999. Status Justification for Listing the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) as Critically Endangered on the 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 3(2):200–224.

[4] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.

[5] Meylan. 1999. Status of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Caribbean Region. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 3(2):177–184. Available at (http://www.iucn-mtsg.org/publications/cc&b_april1999/4.14-Meylan-Status.pdf).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/PDF/Hawksbill-Sea-Turtle.pdf

Atlantic leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea (Atlantic population))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 3/23/1979 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: CT(s), DE(s), FL(b), GA(b), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), VI(b), VA(s) ---

SUMMARY

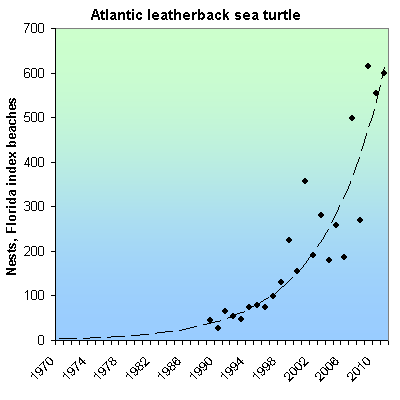

The Atlantic leatherback sea turtles declined due to habitat destruction, commercial fishery bycatch, harvest of eggs, hunting of adults, and loss of beach nesting habitat. It is still threatened by these, and in some places by offshore oil drilling. Globally, leatherback sea turtles have been declining for decades. U.S. populations, however, have increased since being listed as endangered in 1970. Between 1989 and 2011, nests at Florida core index beaches increased from 27 to 615.

RECOVERY TREND

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), the largest living turtle species, is a monotypic genus [1]. It is typically associated with continental shelf habitats and pelagic environments. Adult leatherbacks feed primarily on jellyfish in temperate and boreal latitudes, are highly migratory and have the most extensive range of any extant reptile [1]. Although their oceanic distribution is nearly worldwide, the number of nesting sites is few [3]. Gravid females emerge onto beaches to excavate nests and lay eggs. They prefer high-energy beaches with deep, unobstructed access, which occur most often along continental shorelines [2].

In the western Atlantic, leatherbacks nest from North Carolina to southern Brazil [4]. In U.S. waters, leatherbacks can be found along the East Coast from Maine to Florida, and in the Greater and Lesser Antilles [6]. Critical habitat has been designated as the nesting beaches and adjacent waters of Sandy Point, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands [2]. The Pacific population does not nest in the United States or its territories, but has important foraging areas on the West Coast and near Hawaii [1].

Although Atlantic leatherback populations under U.S. jurisdiction have increased in size since 1970, worldwide their numbers are decreasing. Leatherback numbers have declined in Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Trinidad, Tobago and Papua New Guinea [7]. In 1980 there were more than 115,000 adult female leatherbacks worldwide. In 2005, there were less than 25,000 [6]. The most precipitous declines have occurred in the Pacific Ocean [5]. One study estimated that the number of females in the eastern Pacific decreased from 91,000 in 1980 to 1,690 in 2000 [7]. The number of leatherback nests has also declined at all major nesting beaches throughout the Pacific [6]. Nesting along the Pacific coast of Mexico, which is estimated to represent about 50 percent of all nesting, declined at an annual rate of 22 percent over the last 12 years [6].

CARIBBEAN

In the western Atlantic and Caribbean, the largest nesting assemblages are found in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Florida. Nesting data for these locations have been collected since the early 1980s [6]. Nest numbers in Florida as well as on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Culebra Island, Puerto Rico, increased over the past 20 years [8]. At St. Croix, the number of nests deposited annually on Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, the largest nesting rookery in U.S. territory, ranged from 82 in 1986 to 260 in 1991 [2]. From 1979 on, the trend indicates a 7.5 percent increase per year (SE = 0.014).

FLORIDA

In Florida, several models estimated trends indicating a 9.1 percent increase per year (SE = 0.049) [2]. Florida has established counts on beaches used as "index beaches" where standardized counts have been conducted, allowing for more accurate comparisons between years and between beaches. From 1989 through 2011, leatherback nests at core index beaches numbered from 27 to 615 [9].

Habitat destruction, incidental catch in commercial fisheries, harvest of eggs and flesh, and offshore oil drilling continue to threaten to the survival of the Atlantic leatherback [6]. Entanglement and ingestion of marine debris, including abandoned nets, also pose a threat [1]. Artificial lights on nesting beaches can result in mortality in hatchling turtles by causing newly emerged hatchlings to become disoriented [1]. Eggs can also be lost to beach erosion. At Sandy Point NWR, 40 percent to 60 percent of the eggs laid each year would be lost to erosion if not for human intervention [2]. Because leatherbacks nest in the tropics during hurricane season, there is also potential for storm-related loss of nests. In 1980, only four out of approximately 80 nests laid on Sandy Point NWR survived to hatch following the catastrophic effects of Hurricane Allen [2]. Finally, there is a growing concern that essential beach nesting habitat will be innundated by global warming-induced sea level rise.

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Leatherback Turtle, (Dermochelys coriacea). Silver Spring, MD. 66pp.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Recovery Plan for Leatherback Turtles, (Dermochelys coriacea) in the U.S. Caribbean, Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. Washington, D.C.1992. 60 pp + appendices.

[3] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A.

[4] Rabon, D. R. Jr., S. A. Johnson, R. Boettcher, M. Dodd, M. Lyons, S. Murphy, S. Ramsey, S. Roff, and K. Stewart. 2003. Confirmed Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) Nests from North Carolina, with a Summary of Leatherback Nesting Activities North of Florida. Marine Turtle Newsletter 101:4-8.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2001. Stock Assessment of Leatherback Sea Turtles of the Western North Atlantic.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Leatherback Sea Turtle {Dermochelys coriacea). Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/leatherback.html) accessed December, 2005.

[7] Kaplan, I.C. 2005. A Risk Assessment for Pacific Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 62(8):1710-1719.

[8] Endangered Species Technical Bulletin 22(3):25.

[9] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Research Institute. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available online at http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/. Accessed April 2, 2012.

Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Atlantic DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/10/2001 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(b), DE(b), FL(s), GA(s), LA(s), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MS(s), NH(b), NY(b), NJ(b), NC(b), PR(s), RI(b), SC(b), TX(s), VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

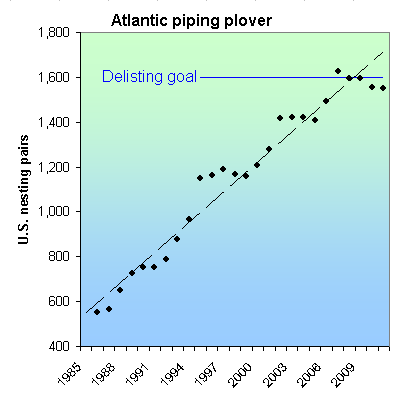

Atlantic piping plover populations initially declined due to hunting and the millinery trade. With these eliminated, it increased in the first half of the 20th century, but began declining after 1950 due to development, beach crowding and predation. It was listed as 1985 after which intensive habitat protection and control of recreationists and predators, increased its U.S. population from 550 pairs in 1986 to 1,550 in 2011, reaching its overall U.S. recovery goal in 3 of the last 5 years.

RECOVERY TREND

The Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus) breeds on Atlantic coastal beaches from Newfoundland to northernmost South Carolina [1]. Hunters and the millinery trade decimated the species in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were stopped by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The plover steadily recovered until about 1950, then began to decline again under pressure from development, beach stabilization programs, increased recreation, and anthropogenically caused increases in predation by native and introduced species.

Following its listing as an endangered species in 1985, the plover was subject to intense nest site, nest area, and predator management programs, resulting in the following population growth between 1986 and 2011 [1, 2, 3]:

POPULATION 1986-2011 GROWTH RECOVERY GOAL YEARS AT RECOVERY GOAL

Canada: 240 - 209 pairs 400 pairs 0

New England 184 - 825 pairs 625 pairs At least 100% of goal, last 14 years

New York/New Jersey: 208 - 431 pairs 575 pairs At least 90% of goal, 6 of last 9 years

South Atlantic: 158 - 294 pairs 400 pairs 0

U.S. population: 550 - 1,550 pairs 1,600 pairs At least 100% of goal, 3 of last 5 years

Total: 790 - 1,759 pairs 2,000 pairs At least 87% of goal, last six years

The 1996 federal recovery plan [1] established the following delisting criteria: 1) Increase and maintain for five years a total of 2,000 breeding pairs, distributed among four recovery units as follows: Canada, 400 pairs; New England, 625 pairs; New York-New Jersey, 575 pairs; Southern (DE-MD-VA-NC), 400 pairs. 2) Verify the adequacy of a 2,000-pair population of piping plovers to maintain heterozygosity and allelic diversity over the long term. 3) Achieve five-year average productivity of 1.5 fledged chicks per pair in each of the four recovery units described in criterion 1, based on data from sites that collectively support at least 90 percent of the recovery unit’s population. 4) Institute long-term agreements to assure protection and management sufficient to maintain the population targets and average productivity in each recovery unit. 5) Ensure long-term maintenance of wintering habitat, sufficient in quantity, quality and distribution to maintain survival rates for a 2,000-pair population.

- The New England unit exceeded its recovery plan goal of 625 nesting pairs each of the 14 years between 1998 and 2011 and cointinues to grow.

- The New York/New Jersey unit grew steadily from 1986 to 2007, the only year in which it reached its recovery plan goal. It declined in all years from 2008 to 2011. While it has been at at least 90% of its goal in six of the nine years ending in 2011, the recent declines are worrisome.

- The Southern recovery unit was relatively stable betwee 1986 and 2003, grew rapidly between 2004 and 2008, then remained relatively stable at a reduced level from 2009 to 2011. It has never reached its recovery goal and has always been the smallest and slowest growing of the three U.S. recovery units.

- The U.S. population as a whole had strong, steady growth between 1986 and 2007, increasinging from 550 to 1,624 pairs. 2007 was the first year it reached its recovery goal of 1,600 pairs. From 2009 to 2011, it declined slightly to 1,550 pairs. The U.S. trend is dominated by the New England recovery unit which is the largest, fastest and most consistently growing.

- The Canadian recovery unit has periods of growth and decline, but remained at 200-250 nesting pairs in almost all years between 1986 and 2011. It the smallest of all the recovery units and the only one not to have experienced net growth since 1986.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), Atlantic Coast Population, Revised Recovery Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts. 258 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Abundance and productivity estimates – 2010 update: Atlantic Coast piping plover population. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/pdf/Abundance&Productivity2010Update.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Preliminary 2011 Atlantic Coast Piping Plover Abundance and Productivity Estimates, March 20, 2012. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/preliminary2011%2020March2012%20for%20AC%20website.pdf

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 214 pp.

Kemp's ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 12/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 9/22/2011 |

Range: AL(o), CT(s), DE(s), FL(o), GA(s), LA(m), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(m), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), PR(o), RI(s), SC(o), TX(b), VI(o), VA(s) ---

SUMMARY

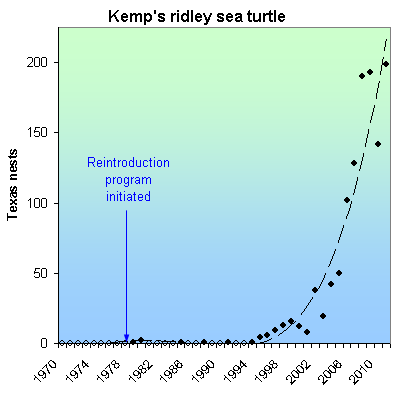

More than 40,000 Kemp's Ridley sea turtles once nested in a single day on one beach in Mexico, but egg collection, oil drilling, development, and commercial fishing extirpated it from the United States by the 1950s. It was listed as endangered in 1970 and was reintroduced to Texas in 1978. There was little progress until 1995. The population reached 199 in 2011. The Mexican population grew from a low of 740 in the mid-1980s to at least 11,600 nests in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

The Kemp's Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) nests only in the Gulf of Mexico [6]. Historical nesting areas are not well known, but have likely always been centered in Mexico. Even less is known about historic population numbers, but as late as 1947, more than 40,000 females nested in a single day on one beach in Mexico. Collection of turtle eggs, development of nesting beaches, commercial fisheries by-catch and oil extraction pushed the species to near extinction by the 1970s.

TEXAS

The Kemp's Ridley sea turtle was extirpated from the U.S. as a breeding species by the 1950s, though it continued to forage in U.S. waters along the Gulf Coast and the Atlantic. In 1978, an international, multi-agency project began to reestablish a nesting colony at Padre Island National Seashore in Texas [5]. From 1978 to 1988, 22,507 eggs were transported from Mexico for incubation and imprinting on the sands and surf of the national seashore. Most hatchlings were transported to a National Marine Fisheries Service laboratory where they were raised away from predators for nine to 11 months. They were then released into the Gulf of Mexico, where it was hoped that they would return to nest on the sands where they were imprinted.

The program proved controversial at first, due to setbacks and little nesting success between 1979 and 1994, but nest counts began to increase in 1995, accelerated in 2004, and reached reaching 199 in 2011 [9, 11, 12, 13].

By 2006, 60 percent of Texas nesting occurred in Padre Island National Seashore [1], with the remainder occurring at seven additional sites: Bolivar Peninsula, Galveston Island, near Surfside (Brazoria County), Mustang Island, South Padre Island, Boca Chica Beach, and Aransas/Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuge [1, 10]. Nesting turtles returned to Matagorda Island, Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuge in 2005 (three nests) and continued to nest in 2006 (four nests), and 2007 (four nests) [10].

OTHER STATES

Very small, sporadic nesting efforts occur in Alabama, Florida and South Carolina. In 1999, single nests were found on the Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama and on Gulf Island's National Seashore in Perdido Key, Fla. [3]. In 2001, a single hatchling was found at Bon Secour and a nest was found at Gulf Shores’ West End Beach, Ala. [2, 3].

MEXICO

The vast majority of Kemp’s Ridley turtles nest on a single beach near Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico. The Mexico population declined from more than 40,000 nests in 1947 to 740 in 1985 before steadily climbing to 10,099 in 2005 and at least 11,600 in 2006 [4, 8, 9]. The increase was facilitated by habitat protection, prohibition and education about egg collection, and the requirement that turtle excluder devices be used by U.S. and Mexican shrimp fishing fleets in the Gulf of Mexico. Prior to their use, the fleet killed 500 to 5,000 turtles annually [6].

CITATIONS

[1] Padre Island National Park. 2007. The Kemp's ridley sea turtle. U.S. National Park Service. Website (http://www.nps.gov/pais/naturescience/kridley.htm) accessed August 30, 2007.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. World's Most Endangered Sea Turtle Nest Discovered Along U.S. Coastline for Only Ninth Time This Year, August 17, 2001 press release. (http://www.fws.gov/southeast/news/2001/al01-001.html)

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Availability of an Environmental Assessment and Receipt of an Application for an Incidental Take Permit for FML81A, LLC, Fort Morgan Peninsula, Baldwin County, AL. May 9, 2002 (67 FR 31359).

[4] Turtle Expert Working Group. 2000. Assessment Update for the Kemp’s Ridley and Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations in the Western North Atlantic. U.S. Dep. Commer. NOAA Tech. Mem. NMFS-SEFSC-444, 115 pp.

[5] Arroyo, B., P. Burchfield, L.J. Pena, L. Hodgson, and Pl Luevano. 2003. The Kemp's Ridley: recovery in the making Endangered Species Bulletin, May-June, 2003.

[6] NOA Fisheries. 2005. Kemp's Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) (www.nmfs.noaa.gov/prot_res/species/turtles/kemps.html)

[8] Caribbean Conservation Corporation and Sea Turtle Survival League. 2006. Sea turtle species of the world. Website (www.cccturtle.org/species_world.htm) accessed January 23, 2006.

[9] Hanna, B. 2006. Slow and steady revives the species. Fort Worth Telegram-Star, July 3, 2006. Available at http://www.texansforkay.com/news/Read.aspx?ID=103

[10] Stinson, T. 2007. Personal communication with Tonya Stinson, Environmental Education Specialist, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Complex, May 22, 2007.

[11] National Marine Fisheries Service et al. 2011. Bi-National Recovery Plan for the Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). Silver Spring, MD. 177 pp.

[12] Shaver, D. 2012. Sea Turtle Nesting Season 2011. Padre Island National Park. www.nps.gov/pais/naturescience/nesting2011.htm

[13] Shaver, D. 2011. Kemp's Ridley nests found on Texas coast, 2000-2010. Padre Island National Park.

Northern Great Plains piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Northern Great Plains DPS))

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 9/11/2002 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: MT, ND, SD, NE, KS, CO, MN, IA, OK; SC, GA, FL, AL, MS, LA, TX, PR

SUMMARY

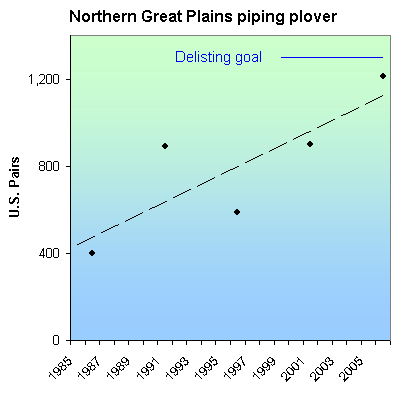

The Northern Great Plains piping plover was listed as endangered in 1986 due to threats from habitat loss, predation and disturbance. The number of Northern Great Plains piping plovers in the United States has increased from about 1,000 adults when ti was listed as an endangered species in 1985 to 2,959 adults in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

In the Northern Great Plains, most piping plovers (Charadrius melodus) nest on the unvegetated shorelines of alkali lakes, reservoirs or river sandbars. The Northern Great Plains population is geographically widespread, with many birds in very remote places, especially in the U.S. and Canadian alkali lakes region, making population monitoring difficult.

The International Piping Plover Census is conducted every five years. The census found that the U.S. portion of the Northern Great Plains piping plover population decreased between 1991 and 1996, then increased in 2001 and again in 2006. In the United States in 1991, there were 2,023 adults and 891 breeding pairs. In 2006, there were 2,959 adults and 1,212 breeding pairs. The population of plovers in Canada increased in 1996, decreased in 2001, and then increased again in 2006. Overall, the number of Great Plains piping plovers has increased from approximately 3,500 birds in 1991 to approximately 4,600 birds in 2006 [1].

The recovery goal in the 1988 recovery plan is for 1,300 pairs in the Northern Great Plains that remain stable for 15 years including 60 pairs in Montana, 650 pairs in North Dakota, 350 pairs in South Dakota, 465 pairs in Nebraska, and 25 pairs in Minnesota [2].

The number of piping plover pairs in Montana increased from fewer than 20 pairs in 1986 to more than 100 pairs in 1992, then fluctuated around 60 pairs from 1994 to 2008. The number of pairs in North Dakota has fluctuated, but increased from around 300 pairs in 1986 to nearly 800 pairs in 2008. The number of pairs in South Dakota increased from around 100 pairs in 1986 to around 250 pairs in 2008. The number of pairs in Nebraska increased from around 100 pairs in 1986 to around 400 pairs in 2008. In Minnesota in 1986, there were approximately 11 plover pairs, but from 2002 to 2008 there were only one to two pairs. A few piping plover pairs are also found in Colorado, Kansas and Iowa. From 1990 to 2008, there were two to 18 pairs in Colorado, two to four pairs in Kansas, and four to seven pairs in Iowa [1].

Modeling strongly suggests that the piping plover population is very sensitive to adult and juvenile survival [1]. Therefore, while there is a great deal of effort extended to improve breeding success, to improve and maintain a higher population over time, it is also necessary to ensure that the wintering habitat, where birds spend most of their time, is secure. While the population increase seen in recent years demonstrates the possibility that the population can rebound from low population numbers, ongoing efforts are needed to maintain and increase the population. In the U.S., piping plover crews attempt to locate most piping plover nests and take steps to improve their success. This work has suffered from insufficient and unstable funding in most areas. In addition to habitat loss, human disturbance, and predation, emerging threats, such as energy development (particularly wind, oil and gas and associated infrastructure) and climate change are likely to impact piping plovers both on the breeding and wintering grounds [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 214 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Great Lakes and Northern Great Plains Piping Plover Recovery Plan. 170 pp.

Puerto Rican parrot (Amazona vittata)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/9/2009 |

Range: PR(b) ---

SUMMARY

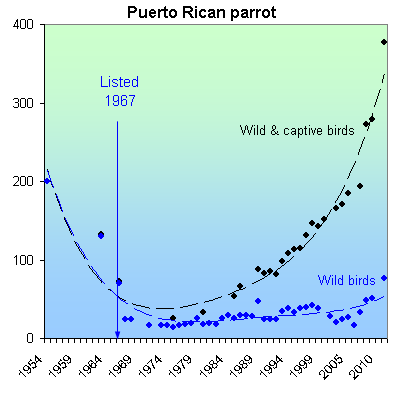

The Puerto Rican parrot declined to near extinction due to deforestation, hunting and hurricane damage. When listed as an endangered species in 1967, there were just 24 birds in one population. Due to habitat protection, captive breeding and predator control, it increased to 377 birds in 2001 in two wild populations and two breeding facilities.

RECOVERY TREND

The Puerto Rican parrot (Amazona vittata) formerly inhabited mature and old-growth forests on Puerto Rico and the adjacent smaller islands of Culebra, Mona, Vieques, and possibly the Virgin Islands [6]. Interspersed with small sandy and marshy areas, these forests covered most of the islands, providing nesting cavities in large, upland trees, and seeds and fruits in upland, lowland, and coast plains forests.

EARLY POPULATION STATUS

Though absolute numbers are not precisely known, 100,000 to 1 million Puerto Rican parrots are believed to have coexisted with the Taino Indians for several hundred years prior to the arrival of Spanish colonists [6]. Also known as Arawak, the Taino came to Puerto Rico from South America, calling it Boriken (or Borinquen), "the land of the great lords." They lived in small villages, sustained by seafood, pineapples, cassava, guava, garlic, sweet potatoes, hunting and wild crafting.

When Columbus landed on Puerto Rico on November 19, 1493, there were between 20,000 and 50,000 Taino on the island and on the order of 1 million to 3 million throughout the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and related islands) [13]. Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Spanish priest living in the Dominican Republic, who championed the rights of indigenous peoples, wrote in 1561 that “between 1494 and 1508 more than three million people died from war, slavery and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself as an eyewitness can scarce believe it.” [8]

By 1513, so few Taino remained that the Spanish began importing slaves from Africa to farm their plantations and mine the mountains [8]. By 1544, just 60 were thought to remain in Puerto Rico. Whether the Taino became extinct, survived in remote Cuban villages, or carried on as a mixed-race people (61 percent of contemporary Puerto Ricans have Native American mtDNA [9]) is controversial, but they were clearly decimated within a decade of Puerto Rico’s colonization.

The Puerto Rican parrot would also be driven to near extinction, but over a much longer period of time. It was still common in 1650, 150 years after colonization [10]. The human population of Puerto Rico was just 880 souls by then, almost entirely Spanish and African and mixed-race slaves. The forests were still largely intact.

In the next 200 years, Puerto Rico’s human population would grow to 500,000 [10]. Vast expanses of forest, especially in the lowlands, were cleared for agriculture. It was during this period that the first significant parrot declines were reported (for example, by the German naturalist Morritz in 1836) [8].

The human population doubled in the next 50 years, reaching 1 million in 1900 [10]. Seventy-six percent of the land area had been converted to agriculture, and remaining forests were highly fragmented, with just 1 percent in an old-growth state [7, 10]. The Puerto Rican parrot was by then extirpated from the outer islands and reduced to five locations on the mainland [6].

In the next 100 years, Puerto Rico’s population would nearly quadruple, reaching 3.7 million in 2011 [12].

RECENT POPULATION STATUS

As the island’s human population continued to grow, its native habitats continued to decline, and its wildlife suffered increasing pressures. The Culebra parrot (A. v. gracilipes), a subspecies of Puerto Rican parrot, was driven extinct by hunting and persecution on Culebra Island in 1912 [14]. By 1937, the Puerto Rican parrot numbered just 2,000 birds [7]. By 1954, only 200 remained, all in the Luquillo Mountains, which was, and is, the largest contiguous tract of native forest on the island. It was preserved as a forest reserve by the Spanish Crown in 1876, and is one of the oldest reserves in the Western Hemisphere. It was made a U.S. forest reserve in 1908 and a national forest in 1935; it is now the El Yunque National Forest [7]. The population dwindled to 130 in 1963, 70 in 1966, and 24 in 1967 [2, 6, 7].

In 1967, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service placed the Puerto Rican parrot on the nation’s first endangered species list and established a recovery program the following year composed of the Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Biological Survey, the Puerto Rico Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, and many academic and independent scientists [6].

The wild parrot population continued to fall after being listed as endangered, reaching a low of 14 wild birds in 1975 [2, 6, 7, 14]. After that, conservation actions began to bear fruit and the number of birds in the wild increased to 47 in 1989. That same year, though, the island was hit by Hurricane Hugo, leaving just 24 wild birds in 1990.

Between 1990 and 2011, the captive Puerto Rican parrot population grew fairly steadily from 59 to about 300 [6, 13]. The wild population, however, has struggled. Between 1990 and 1998, it grew steadily from 24 to 42 birds. In 1998 Hurricane George caused extensive damage to eastern Puerto Rico. Thereafter, the wild parrot population declined almost steadily to 16 in 2006, the second lowest level ever recorded. Since then, however, the population has increased dramatically to 77 in 2011 through expansion of the captive-breeding and reintroduction program, establishment of a second wild population, and better understanding of reproductive limitations.

CAPTIVE BREEDING

In 1973 the Luquillo Aviary was established in an abandoned Army building in the Caribbean National Forest (now the Yunque National Forest) to secure the population against extinction should all wild birds die, and to augment the wild population with captive-reared birds [6]. The building was old, inadequate and poorly located, but was the only available federal facility in proximity to the Luquillo Mountains. In 2007, it was replaced by a new facility, the Iguaca Aviary, also run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 1993, a second captive-breeding facility, the José L. Vivaldi Aviary, was built with a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service matching grant, state funds and private contributions in the Rio Abajo Forest [6] to expand the breeding program and insure against the Luquillo Aviary being destroyed by a hurricane. It is run by the Puerto Rico Department of Environmental and Natural Resources.

IMPROVING NESTING SUCCESS

Prior to 1973, nesting success (=fledging of at least one chick) ranged from 11 percent to 26 percent [6], which in the best of circumstances would sustain only slow growth, and in actuality was not sufficient to offset mortality. The recovery program sought to increase nesting success by improving the quality and quantify of nesting habitat, protecting nest areas from disturbance and controlling non-native predators and competitors. All breeding pairs since 1976 have used created or modified nest sites designed to prevent entry of water and discourage entry by predators and competitors. By 1987, nesting success increased to 81 percent. Efforts were intensified after Hurricane Hugo.

Nesting success has also be improved by fostering aviary-born chicks in wild nests, rescuing imperiled chicks and returning them to the wild, and release of breeding age birds into the wild [6].

CREATING A SECOND POPULATION

In 1989, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources entered into an agreement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to manage the 5,850-acre Rio Abajo Forest to enhance its potential as a future parrot reintroduction site [6]. In 2006, 22 birds were reintroduced. The wild population there has since grown to 55 birds [6, 13], and in 2011 was twice as large as the El Yunque population.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Revised Recovery Plan for the Puerto Rican Parrot, Technical/Agency Draft. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region, Atlanta, GA

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Puerto Rican Parrot Five-Year Review. Available at https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc1989.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Three is a charm. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service press release, May 14, 2002.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Flight freedom. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service press release, May 3, 2004.

[5] Puerto Rico Department of Environmental and Natural Resources. 2005. Puerto Rico's Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Recovery Plan for the Puerto Rican Parrot, Second Revision. Available at http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/090617.pdf

[7] Meyers, M.J. Puerto Rican parrots. National Biological Service, Patuxent Environmental. Available at http://boricua.com/la-isla/puerto-rican-parrots. Accessed May 8, 2012.

[8] Rouse, I. 1993. The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus. Yale University Press (New Haven)

[9] Martínez Cruzado, J. C. 2002. The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean: Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic. Kacike: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology

[10] Snyder, N.F.R., J.W. Wiley and C.B. Kepler. 1987. The parrots of Luquillo: natural history and conservation of the Puerto Rican parrot. Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

[11] Library of Congress. Abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico. Website available at http://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/slaves.html

[12] World Population Review. 2012. Puerto Rico population 2012. Website available at http://worldpopulationreview.com/puerto-rico-population-2012/

[13] Fox, B. 2011. Endangered Puerto Rican Parrot on the Rise. Associated Press, June 15, 2011 available at http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/wireStory?id=13929877#.T6mgQujE_nh

[14] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Puerto Rican Parrot Release. Press release available at http://library.fws.gov/Pubs4/PR_parrot_release.pdf.

Puerto Rican plain pigeon (Columba inornata wetmorei)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/14/1982 |

Range: PR(b) ---

SUMMARY

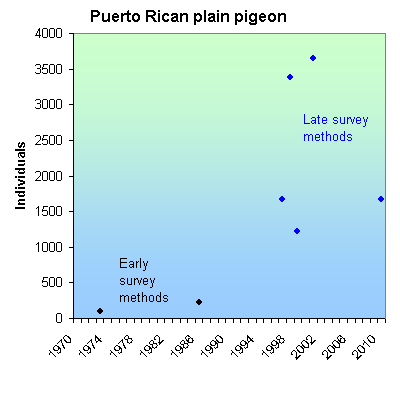

Hunting and clearing of forests for agriculture caused the once-abundant Puerto Rican plain pigeon to decline to near extinction. The pigeon remains highly threatened by habitat loss for development, hurricane damage to forests and low bird density. Survey methods have changed, making population comparisons difficult. Overall the total population of pigeons has fluctuated but increased from a few hundred survivors at listing in 1970 to an estimated population of about 1,600 birds in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Puerto Rican plain pigeon (Columba inornata wetmorei) was common and widespread in the foothills and valleys of Puerto Rico in the 1800s, but declined to near extinction in the 1920s and 1930s due to unregulated hunting, clearing of forests for agriculture, and hurricane damage to forests [1]. It was feared to be extinct when a small population was discovered in eastern Puerto Rico in 1963. It was placed on the endangered species list in 1970 and has increased in population size since listing due to a prohibition on shooting, protection and restoration of forest habitats, and a captive breeding program (established at the University of Puerto Rico’s Hamacao Campus in 1984).

Due to differences in survey methods, it is difficult to quantify absolute change in population size, but the total population of the pigeon has increased since it was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1970. The area of occupancy has increased, but the pigeon remains limited to eastern Puerto Rico. Habitat loss continues to be the main threat at the center of abundance in east-central Puerto Rico. The pigeon remains at high risk of extinction due to low density, ongoing habitat loss, and the threat of hurricane damage and other stochastic events. The pigeon is very sensitive to hurricane damage to its habitat, and was negatively impacted by Hurricane Hugo in 1989 and by Hurricane Georges in 1998 [3].

Counts conducted from 1973 to 1983 in known roosting areas estimated that the population in the species’ core habitat increased from approximately 100 birds from 1973-1983 to 218 birds from 1986-1992 [2]. Theses counts were of a small area, were not adjusted for detection probability, and likely underestimate the total population size at the time [5]. Since then, population estimate methodologies have changed, making it difficult to quantify change in population size, but total population has been estimated at more than 1,000 birds since 1997 [5]. In 1998 the population was estimated at more than 3,000 birds, but following Hurricane Georges the population declined to 1,200 birds in 1999. The population then rebounded to more than 3,000 birds in 2001, but then declined again, to about 1,600 birds in 2010 [5].

The 1982 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan calls for the establishment of two populations with at least 250 nesting pairs each [4]. The total population is much larger than 500 pairs, but it is not clear if they exist in one or more distinct populations. Regardless, it’s questionable whether 500 nesting pairs constitute a non-endangered status in Puerto Rico's current landscape. The recovery plan should be updated and a population viability assessment should be conducted.

CITATIONS

[1] Rivera-Milán, F.F., C.R. Ruiz, J.A. Cruz, M. Vázquez, and A.J. Martínez. 2003. Population monitoring of Plain Pigeons in Puerto Rico. Wilson Bulletin 115: 45–51.

[2] Rivera-Milan, F.F. 2005. Monitoring of pigeon and dove populations on Puerto Rico and Territorial Islands (1986-2005). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, unpublished manuscript, October 3, 2005.

[3] Rivera-Milán, F.F., C.R. Ruiz, J.A. Cruz, and J.A Sustache. 2003. Reproduction of Plain Pigeons (Columba inornata wetmorei) in east-central Puerto Rico. The Auk 120(2):466-480.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982. Puerto Rican Plain Pigeon Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, Ga. 52 pp.

[5] F.F. Rivera-Milán. 2011. Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, personal communication.

Virgin Islands tree boa (Epicrates monensis granti)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 3/27/1986 |

Range: PR(b), VI(b) ---

SUMMARY

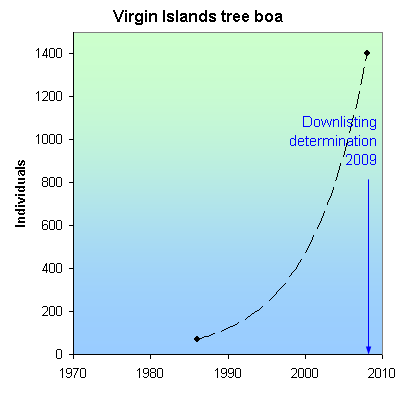

The Virgin Islands tree boa is threatened by habitat destroying development, introduction of predatory mongooses, cats, and rats, and sea level rise. It was listed as endangered in 1970. In 1986, there were 71 snakes in four populations. Wild populations have increased and two new ones have been created. In 2008, 1,400 snakes were known in six populations. In 2009 it was recommended for downlisting.

RECOVERY TREND

The Virgin Islands boa (Epicrates monensis granti), a blotched brown semi-arboreal snake, inhabits subtropical dry forests where it hunts at night, primarily eating sleeping lizards [2]. During the day, it hides in termite nests or under rocks and debris [3].

It's limited historic range extends from Puerto Rico eastward into the British Virgin Islands [1]. In Puerto Rico, it currently inhabits Cayo Diablo, Cayo Ratones, Culebra and Río Grande. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, it is restricted to extreme eastern St. Thomas [2]. The disjunct current distribution indicates a decline from historical levels [2].

When conditions are favorable, this species can exist in high densities on small islands [1]. Large-scale habitat destruction and the introduction of exotic mammalian predators have caused severe population declines [1]. The introduction of the Indian mongoose on St. Thomas, St. John, Tortola and Jost Van Dyke contributed to population declines on these islands [3]. Feral and domestic cats, which prey on adult boas, have become ubiquitous on St. Thomas [1]. Two rat species, also introduced on many islands, are potential predators of young boas [3].

Development on the east end of St. Thomas threatens the remaining boa population there [1]. Currently, the small, uninhabited cays and islets where much of the remaining populations have become concentrated tend to be vulnerable to inundations from the ocean and storms [4].

It was listed as an endangered species in 1970.

A federal recovery plan was developed in 1986 at which time only 71 snakes were known. A Mona/Virgin Islands Boa Species Survival Plan was developed in 1990 [1].

A captive breeding program was initiated by the Toledo Zoological Gardens in 1985, and reintroductions were initiated on Cayo Ratones in 1993 and Stevens Key in 2002 [1, 5, 6]. On the former, 31 reintroduced boas increased to 482 snakes by 2004 [6]. On the latter, 42 introduced snakes increased to 170 by 2007 [5, 6].

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended downlisting the Virgin Islands tree boa in 2009 [6].

CITATIONS

[1] Tolson P.J, and M. A. Garcia. AZA Species Survival Plan Profile Mona/Virgin Islands Boa: A U.S./Puerto Rico Partnership Seeks to Recover Endangered Boa. Accessed at http://www.umich.edu/~esupdate/library/97.01 02/tolson.html

[2] Platenberg, R. J., F. E. Hayes, D. B. McNair, and J. J. Pierce. 2005. A Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Plan for the U.S. Virgin Islands. Division of Fish and Wildlife, St. Thomas. 216 pp.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Species Account, Virgin Islands Tree Boa. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Endangered Species. http://www.fws.gov/endangered/i/c/sac0q.html

[4] American Zoo and Aquarium Association. 1998. Virgin Islands Boa 98 Fact Sheet. Accessed at http://www.nagonline.net/Fact%20Sheet%20pdf/AZA%20-%20Virgin%20Islands%20Boa%20Species%20Survival%20Plan.pdf

[5] Peter J. Tolson. 2006. Personal Communication.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Virgin Islands Tree Boa (Epicrates monensis granti) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Boquerón, Puerto Rico. 25 pp.