| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/11/1984 | Recovery plan: 9/28/1990 |

Range: GU, MP

SUMMARY

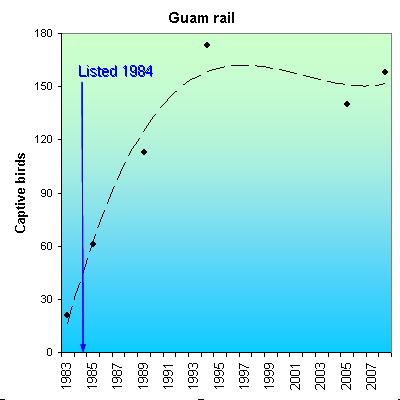

The Guam rail is threatened by predation by brown tree snakes, feral cats and other introduced species. It declined catastrophically from 18,000 to less than 100 birds between 1968-1983 as brown tree snakes spread across the island. Only two wild birds were seen after it was listed as endangered in 1984. It was extirpated from the wild in 1985. The captive population grew from 21 birds in 1983 to 158 in 2008. Still extant wild populations were created 1989 (Rota) and 2010 (Guam).

RECOVERY TREND

The Guam rail, or ko‘ko‘, (Rallus owstoni) is a flightless bird endemic to the island of Guam, a U.S. territory at the southern end of the Mariana Islands chain. It formerly occurred island-wide in most nonwetland habitats [5].

Though habitat loss, hunting and DDT spraying may have reduced its population level to some degree, the rail was estimated at 80,000 birds in the 1960s [13] and was still common as of 1969 [1]. Thereafter it suffered what may be the most rapid, catastrophic population decline of any U.S. bird species. The decline began in southern Guam in 1971, resulting in its extirpation there in the mid-1970s [1]. In northern Guam the decline began in 1972, resulting in the complete extirpation of the species from the wild by 1986 [1, 5].

Between 1976 and 1982, roadside rail counts declined by 99.8 percent (80.4/100 km to 0.2) [7].

The Guam rail’s rapidly shrinking range mirrors the expanding range of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), a native of Indonesia, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and northern Australia [18]. It was positively identified on Guam in the 1950s, but may have been seen in the 1940s, and was likely transported from the Admiralty Islands by the U.S. military during a large World War II buildup. The rail disappeared from areas where snake densities reached high levels, until the very last low-snake density area in extreme northwest Guam was overrun in the late 1970s. It was not alone: The brown tree snake had a devastating effect on all of Guam's native forest birds, resulting in all 12 being listed as endangered by the territory in the 1970s and eight of them by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1970, 1977 and 1984.

Though extirpated from the south, the Guam rail remained well distributed and fairly common in the north in 1976 and 1978 [14]. By 1981, though, it was reduced to about 2,300 birds, with the largest concentration on Andersen Air Force Base [2, 5]. By 1983, it was confined to two isolated populations totaling fewer than 100 birds: the Northwest Field (a military landing strip not used since 1949) and the flightline of Andersen Air Force Base [3, 5, 8].

By March 1984, rails were extremely rare in the Northwest Field and the flightline population, though the largest remaining, was reduced to 70 acres [4, 5]. The latter was also threatened by a land-clearing proposal, prompting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to emergency-list the Guam rail as an endangered species in April 1984 [9] and finalize the listing in August 1984 [8].

Following its listing, the Guam rail was seen twice in the wild: one bird in 1985 and another in 1986 [5, 16].

CAPTIVE BREEDING AND REINTRODUCTION

By 1983 the rail’s plight was so dire that a captive-breeding program was initiated by the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. Between 1983 and the cessation of captures in 1985 owing to the disappearance of wild birds, 21 rails were brought into captivity [5, 11, 15, 16]. These are the sole founders of all rails in existence today.

Beginning in 1984, captive rails were transferred to mainland facilities [5] and now occur in at least 17 facilities on Guam and the mainland [6, 11]. The first successful reproduction in captivity occurred in 1984 in the Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources facility [5].

In 1983 there were 21 birds in captivity [11], in 1985, 61 [5], in 1989, 113 [15], in 1994, 173 [11], in 2005, 140 [12] and in 2008, 158 [6].

GUAM - ANDERSEN AIR FORCE BASE

Guam rails have twice been released on Andersen Air Force Base, but neither effort resulted in a persisting population [6]. In 1998, 16 birds were released in Area 50, a 60-acre zone surrounded by a snake barrier and managed internally with snake trapping. Rails bred in the wild, but their population was extirpated by feral cats and other predators sometime before 2008.

In 2003, 44 rails were released into a snake-reduced zone within the Air Force Munitions Storage Area [6]. Feral cats killed 80 percent of radio-collared birds. Efforts to eliminate the cats were hampered by lack of permission. The population is believed to have been extirpated sometime before 2008 [6].

GUAM - COCOS ISLAND

On November 15, 2010, 16 captive-bred ko‘ko‘ birds were released into the wild on Cocos Island, on lands managed by the Cocos Island Resort and the Guam Department of Parks and Recreation [17]. No brown tree snakes exist on the island. Rats were eradicated prior to the release.

ROTA

Between 1989 and 2008, 918 Guam rails were introduced to the island of Rota [6]. Though Rota is near to, and has essentially the same habitat as, Guam, it is outside the rail’s historic range. The Fish and Wildlife Service very rarely introduces an endangered species outside its historic range, but was driven to do so because of the ubiquitous presence of brown tree snakes throughout Guam and the dominance of feral cats in the few places where snake levels have been reduced. If successful, establishment of wild rails on Rota will help preserve a wild genetic makeup under natural selection pressures and potentially provide a source of wild-born rails for a future Guam reintroduction.

Reproduction in the wild in Rota was first documented in 1995 [6]. In 2007 the population consisted of 60-80 birds in the Duge and Apanon areas. Predation by feral cats, however, is the population's primary cause of mortality, requiring cat control and continued introduction of captive bred birds to maintain the population [6].

[1] Jenkins, J.M. 1979. Natural history of the Guam rail. Condor 81:404-408.

[2] Engbring, J. and F.L. Ramsey. 1984. Distribution and abundance of the forest birds of Guam: Results of a 1981 survey. U.S. Fish Wildlife Service FWS/OBS-84/20.

[3] Aguon, C.F. 1983. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam. IN: Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, Annual Report, FY 1983. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

pp 143-157.

[4] Beck, R.E., Jr. 1984. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam. IN: Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, Annual Report, FY 1984. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

Pp 139-150.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990. Native Forest Birds of Guam and Rota of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Island Recovery Plan. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu, HI. Available at: http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plans/1990/900928b.pdf

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Ko‘ko‘ or Guam Rail (Gallirallus owstoni) 5-Year Review, Summary and Evaluation https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2529.pdf

[7] Aguon, C.F. 1982. Survey and inventory of native land birds on Guam and Northern Marianas Islands. IN: Guam Aquatic Wildlife and Resources Division Annual Report, FY 1982. Department of Agriculture, Guam.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Determination of endangered status for seven birds and two bats on Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. July 27, 1984 (49 FR 33881). http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr875.pdf

[9] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Determination of endangered status for the Guam rail. April 11, 1984 (49 FR 14354). http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr814.pdf

[10] Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. 2012. Guam Rail / Ko‘ko‘. Website http://www.guamdawr.org/learningcenter/factsheets/birds/rail_html. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[11] Haig, S.M., and J.D. Ballou. 1995. Genetic Diversity in Two Avian Species Formerly Endemic to Guam. The American Ornithologists Union. 112(2):445-455.

[12] Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources. 2005. Guam Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy. http://www.guamdawr.org/Conservation/gcwcs2/GuamCWCS%20Chapter3.pdf

[13] Lint, K.C. 1968. A rail of Guam. Zoo Nooz 41:16-17

[14] Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner and D.G. Berret. 1979. America's unknown avifauna: The birds of the Mariana Islands. American Birds 33(3):227-235.

[15] Haig, S.M., J.D. Ballou and S.R. Derrickson. 1990. Management options for preserving genetic diversity: Reintroduction of Guam rails to the wild. Conservation Biology 4(3):290-300.

[16] Haig, S. M., Ballou, J. D. and N. J. Casna. (1994) Identification of kin structure among Guam rail founders: A comparison of pedigrees and DNA profiles. Mol. Evol., 3:109-119.

[17] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Guam Rail / Gallirallus owstoni / Ko‘ko‘. Website: http://www.fws.gov/pacificislands/fauna/guamrail.html. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[18] Enbring, J. and T.H. Fritts. 1988. Demise of an insular avifauna: the brown tree snake on Guam. Transactions of the Western Section of the Wildlife Society 24:31-37.

Pacific green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizi)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 1/12/1998 |

Range: AS(b), CA(s), GU(b), HI(b), MP(b), OR(o), WA(o) ---

SUMMARY

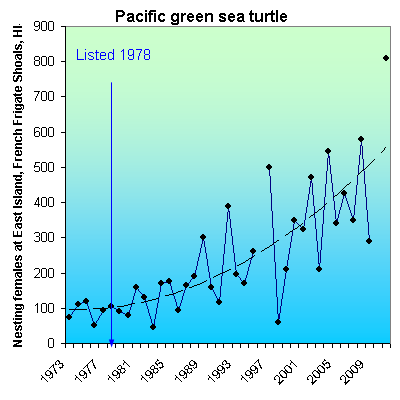

Green sea turtles in the Pacific are threatened by habitat loss, egg collection, hunting, beach development, bycatch mortality in commercial fisheries, and sea level rise due to global warming. Since being protected in 1978, the number of females nesting at East Island of French Frigate Shoals, approximately half of the total Hawaii population, increased from 105 in 1978 to 808 in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 5]. It migrates long distances between foraging and nesting areas [5]. Typical near-shore habitats are shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches. Females generally reproduce every two or more years, with an average of three to four nests during a breeding year.

U.S. populations occur in the Atlantic from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean, and in the Pacific from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 5]. Nesting populations within the United States have increased in size since the species was protected in 1978.

The taxonomic distinctions between Pacific and East Pacific populations of green sea turtle are under review. It remains unresolved whether C. mydas agassizii qualifies as a separate species or a subspecies of green sea turtle.

HAWAII AND THE FAR PACIFIC

In Hawaii, most nesting occurs at East Island of French Frigate Shoals [2, 6]. Nesting females increased there from 75 in 1973 to 808 in 2011 due to cessation of hunting and protection of habitat [6, 8]. The number of nesting females at East Island represents approximately half of the estimated number of nesting females in all of Hawaii [9].

Other U.S.-associated Pacific Islands that support green sea turtle populations include American Samoa (25-35 nesting females), the Federated States of Micronesia (three atolls, more than 100 nesting females) and Guam (little but regular nesting) [2]. In general, the major threat on urbanized Pacific islands is habitat loss and problems associated with rapidly expanding tourism. In particular, human development is having an increasingly serious impact on green sea turtle nesting beaches. On rural and developing islands, including American Samoa and some islands of the Northern Mariana Islands and Micronesia, human consumption of turtles remains a problem. The relatively recent increase in fibropapillomatosis (a tumorous disease) is a concern [2].

U.S. MAINLAND

The population status and migratory habits of East Pacific green turtles frequenting waters off the U.S. West Coast are unknown, and there are no known nesting sites in the United States [3]. Severe population declines in this population over the past 30 years were due largely to massive overharvesting of wintering turtles in the Sea of Cortez from 1950-1970 and intense collection of eggs between 1960 and early 1980 on mainland beaches of Mexico. The population was thought to be declining as of 1998. A small group (30-50) of resident East Pacific green sea turtles is found in San Diego Bay. Although they do not nest in the United States, this group appears to remain in the area for much of the year because of the warm water effluent from a power-generating station [2]. There is a ban on high-speed boat traffic in the south portion of the bay, but it is rarely enforced and boat strikes may pose a threat [2].

CITATIONS

[1] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, Maryland.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[3] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the East Pacific Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. National Marine Fisheries Service, Washington, DC.

[6] Tiwari, M., G.H. Balazs and S. Hargrove. 2010. Estimating carrying capacity at the green turtle nesting beach of East Island, French Frigate Shoals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 419:289–294.

[7] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 105 pp.

[8] Maison, K.A., I. Kinan Kelly and K.P. Frutchey. 2010. Green Turtle Nesting Sites and Sea Turtle Legislation throughout Oceania. U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-F/SPO-110, 52 pp. http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/tm/110.pdf

[9] Ishizaki, A. 2012. Personal communication. Protected Species Coordinator, Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. May 19, 2012.

Palau fantail (Rhipidura lepida)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: PL(b) ---

SUMMARY

The Palau fantail was virtually eliminated by damage caused by World War II. It was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1970, and threats to the species were largely abated. In 2011 it is considered to be a species of least conservation concern. The species rebounded following near extirpation. Surveys conducted from 1976-1979 found it to be common, and it was delisted in 1985. It is now abundant to common on most Palau islands. As of 2011, the population is thought to be increasing.

RECOVERY TREND

The Palau fantail (Rhipidura lepida) is one of three Palau bird species that were virtually eliminated by damage caused to the Palau Islands (formerly a U.S.-administered United Nations Trust Territory now under an independent constitutional government) during WWII [1]. Surveys conducted from 1976 to 1979 found the fantail to be one of the more common birds in forests throughout the Palau Islands and categorized the species as abundant on Pelelui Island where previously it had been considered scarce [2]. The authors of this survey suggested that the Palau fantail was no longer endangered [2]. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Palau fantail, along with the Palau ground dove and the Palau owl, from the endangered species list in 1985 [1].

The global population size has not been quantified, but the species is described as abundant on Peleliu, and common on most other islands although uncommon on Koror [3]. As of 2011, the population is thought to be increasing [3].

CITATIONS

[1] Noecker R.J. 1998. Congressional Research Service, Report for Congress: Endangered Species List Revisions: A Summary of Delisting and Downlisting. Made available by National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington D.C.

[2] Pratt H.D., J. Engbring, P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1980. 1976-1979 Notes on the taxonomy, natural history, and status of the resident birds of Palau. Condor 82(2): 117-131.

[3] BirdLife International. 2011. Species factsheet: Rhipidura lepida. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=6017.

Palau ground dove (Gallicolumba canifrons)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: PL(b) ---

SUMMARY

The Palau ground dove was virtually eliminated by damage caused to the island during World War II. The primary potential threat to the species today is the potential introduction of alien species such as rats or brown tree snakes. Although populations had been decimated, surveys conducted from 1976-1979 observed Palau ground doves on all major limestone islands. In 1991 the population was estimated at 500. As of 2011 it is thought to remain stable.

RECOVERY TREND

The Palau ground dove (Gallicolumba canifrons) is one of three Palau bird species that were virtually eliminated by damage caused to the Palau Islands (formerly a U.S. administered United Nations Trust Territory now under an independent constitutional government) during World War II [1]. Surveys conducted from 1976 to 1979 observed Palau ground doves on all major limestone islands from Koror to Angaur [2]. Although they were considered rare or uncommon on these islands, scientists thought this could be due to difficulty detecting Palau ground doves when they were present [2]. Because the Palau ground dove is not sought as a game species, and the constitution of Palau has banned the personal possession of firearms, hunting is not a threat to this species [1]. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Palau ground dove, along with the Palau fantail flycatcher and the Palau owl, from the endangered species list in 1985 [1]. The 2011 population is estimated to be stable at around 500 birds [2, 3].

CITATIONS

[1] Noecker R.J. 1998. Congressional Research Service, Report for Congress: Endangered Species List Revisions: A Summary of Delisting and Downlisting. Made available by National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington D.C.

[2] Pratt H.D., J. Engbring, P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1980. 1976-1979 Notes on the taxonomy, natural history, and status of the resident birds of Palau. Condor 82(2): 117-131.

[3] BirdLife International. 2011. Species factsheet: Gallicolumba canifrons. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=2622.

Palau owl (Pyroglaux podargina)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: PL(b) ---

SUMMARY

The Palau owl was virtually eliminated by damage caused to the island during World War II and later may have been threatened by the introduction of a beetle that was poisonous when ingested by the owls. Surveys conducted in 1976 found the owls to be abundant throughout the archipelago and in 1985, the owl was delisted. In 2011 the owl is considered a species of least conservation concern.

RECOVERY TREND

The Palau owl (Pyrroglaux podargina) is one of three Palau bird species that were virtually eliminated by damage caused to the Palau Islands (formerly a U.S. administered United Nations Trust Territory now under an independent constitutional government) during World War II [1]. Surveys conducted in 1945 found that the endemic owl, reported to be common in 1931, was scarce [2]. The population is thought to have continued to decline until the 1960s, possibly due to deaths caused by the ingestion of an introduced beetle [2]. Following efforts to control the introduced beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros), also a pest on coconut plantations, owl populations began to increase [2]. A 1976 to 1979 survey found Palau owls to be abundant throughout the archipelago [2] and in 1985, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Palau owl, along with the Palau ground dove and Palau fantail flycatcher, from the endangered species list [1]. As of 2011 the population remains stable [3].

CITATIONS

[1] Noecker R.J. 1998. Congressional Research Service, Report for Congress: Endangered Species List Revisions: A Summary of Delisting and Downlisting. Made available by National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington D.C.

[2] Pratt H.D., J. Engbring, P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1980. 1976-1979 Notes on the taxonomy, natural history, and status of the resident birds of Palau. Condor 82(2): 117-131.

[3] IUCN. 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/143216/0.

Tinian monarch (Monarcha takatsukasae)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: MP(b) ---

SUMMARY

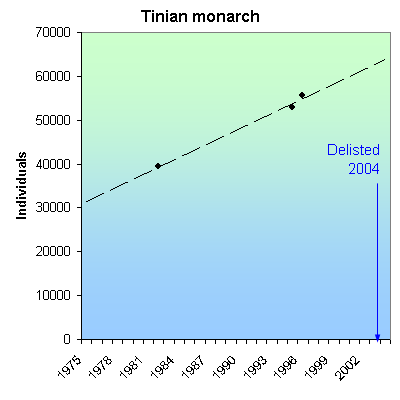

The removal of native forests for sugarcane production prior to World War II and military activities during the war caused the Tinian monarch, a forest bird endemic to Tinian Island, to reach critically low levels. The Tinian monarch adapted well to shrubby vegetation seeded following WWII. After its population reached 39,338 in 1982, the monarch was proposed for downlisting; a continued increase led to the species’ delisting in 1999.

RECOVERY TREND

The Tinian monarch (Monarcha takatsukasae) is a forest bird endemic to the island of Tinian in the Mariana Archipelago [1]. The removal of native forests for sugarcane production prior to World War II and military activities during the war caused the Tinian monarch population to reach critically low levels [1, 2]. The species was listed as endangered in 1970 [1].

Following the war, the U.S. military seeded much of Tinian with a shrubby legume to which the Tinian monarch adapted well [2]. Surveys conducted in 1982 estimated the Tinian monarch population at 39,338 [1]. This prompted the downlisitng of the monarch to “threatened” in 1987 [1]. In 1994 and 1995, the population was estimated at 52,900 and in 1996, a replication of the 1982 surveys produced an estimate of 55,720 [1]. The 1996 survey also found that forest density had increased indicating that the quality of the monarch’s habitat had improved as well [1]. In 1999 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed delisting the Tinian monarch and in 2004 the final rule to delist the species was published [1]. Although current agricultural development is expected to remove some forest habitat, much of the land on Tinian is leased by the U.S. Navy for training, and development in these areas is expected to be minimal [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Draft Post-delisting Monitoring Plan for the Tinian Monarch (Monarcha takatsukasae): Notice of Availability. Federal Register December, 13, 2004. (69 FR 72211-72212)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Proposal to remove the Tinian Monarch flycatcher from the list of threatened and endangered species. Federal Register November 1, 1985 (50 FR 45632-45633].