Apache trout (Oncorhynchus gilae apache)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 9/9/1977 | Listed: 9/9/1977 | Recovery plan: 6/23/1983 |

Range: AZ(b) ---

SUMMARY

Overfishing, habitat degradation and the stocking of nonnative salmonids reduced the Apache trout's range from 600 miles to fewer than 30 stream miles in 12 streams. Hybridization is an ongoing threat. Due to recovery efforts, the number of Apache trout has increased dramatically. As of 2010, there were 29 self-sustaining populations, nearing the goal of 30 populations outlined in the recovery plan.

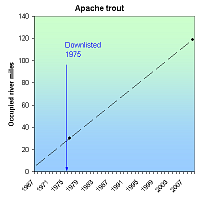

RECOVERY TREND

The Apache trout (Oncorhynchus gilae apache) once occupied approximately 600 miles of stream habitat in the upper Salt River, San Francisco River, and Little Colorado River watersheds of Arizona [1]. By the 1940s it occupied fewer than 30 stream miles and occurred in only 12 streams on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation [1, 2]. Overfishing, habitat degradation and the stocking of nonnative salmonids (starting in 1920, stocking occurred in numerous streams supporting Apache trout) were the cause of this decline [3]. Today, due to recovery efforts, the number of Apache trout in remaining habitat has increased and the number of self-sustaining populations has increased [2]. The Apache trout is now present on the Apache-Sitgreaves, Coronado, and Kaibab national forests, on Fort Apache Reservation, on Arizona State’s Black River Lands, as well as on private land.

Management for Apache trout began in 1955 when the Fort Apache Indian tribe banned sportfishing on all streams containing known populations of Apache trout within the boundaries of the Mount Baldy Wilderness Area [4]. In 1963 the White Mountain Apache tribe, in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Arizona Game and Fish Department, began a captive propagation program using fish taken from some of the 13 pure historic lineages of Apache trout found on the reservation [1]. Before captive bred fish were released, fish barriers were constructed on several streams to prevent upstream migration by exotic fish species [1]. The first stocking attempt occurred in 1965 into Mamie Creek [1]. Early stocking and renovation attempts were not always successful and sometimes hybrid stock were introduced [1]. By the 1970s, when the Apache trout was officially listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, introductions had been made into 12 streams, eight of which historically were known to support Apache trout. Releases at sites outside of the Apache trout’s historic range (e.g. streams in the Pinaleno Mountains and in North Canyon on the Kaibab plateau) were conducted in order to provide angling opportunities [1]. Since 1983, the Alchesay-Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery complex, located on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation, has produced several million Apache trout specifically for restoring sport fishery in streams while still maintaining the species' genetic integrity [2].

Restoration and reintroduction efforts have also taken place on federal land [2, 3]. On the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, the construction of barriers to exclude nonnative fish began in 1979 [3]. Barriers have been erected in at least 13 streams [3] and numerous streams have been stocked with Apache trout from the Alchesay-Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery [2]. Also, beginning in the 1980s, the exclusion of livestock from streams was initiated and 100 miles of stream on U.S. Forest Service lands were fenced to restore riparian and Apache trout habitat [3]. The species was downlisted from “endangered” to “threatened” in 1975 [8].

Currently, the largest concentrations of Apache trout occur on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in the headwaters of the White and Black river drainages [5]. Some of the larger streams such as Bonita Creek and East Fork White River may carry several thousand Apache trout [5]. In addition to the Apache trout in streams, a stock population is maintained at the Alchesay-Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery [5]. In 2010 there were 32 populations of Apache trout, 29 of which were identified as self-sustaining [9]. This is approaching the recovery criteria of 30 self-sustaining populations outlined in the recovery plan [2].

Although Apache trout populations have increased, they still face the threats of habitat loss and degradation and genetic contamination. Nonnative trout continue to be stocked in Arizona streams [3]. Stocking of nonnatives undoubtedly limits the potential range expansion of Apache trout that still inhabits only a fraction of its former range [7].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983. Arizona Trout (Apache trout) Recovery Plan . Albuquerque, NM.

[2] Springer, C.L. 1999. Apache Trout: on the brink of recovery. Endangered Species Bulletin XXIV(4).

[3] Robinson, A. T., L. D. Avenetti, and C. Cantrell. 2004. Evaluation of Apache trout habitat protection actions. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch, Technical Guidance Bulletin No. 7, Phoenix. 19pp.

[4] Arizona Game and Fish Department. 2004. Apache trout chronology. Webpage <http://www.gf.state.az.us/w_c/apache_chronology.shtml> accessed April, 2006.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Apache Trout Species Profile. Website accessed April, 2006.

[6] Arizona Game and Fish Department. Animal abstract, Apache Trout. Heritage Data Management System. Available at <http://www.azgfd.gov/w_c/edits/documents/Oncoapac.fo.pdf>.

[7] New Mexico Game and Fish. 2000. Apache Trout Species Account. Biota Information System of New Mexico BISON version 1/2000. Website <http://www.cnr.vt.edu/fishex/nmex_main/species/010582.htm> accessed April, 2006.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1975. Proposed Threatened Status for 3 Species of Trout (Lahontan cutthroat, Paiute cutthroat, Arizona trout, Salmo clarki henshawi, Salmo clarki seleniris, Salmo apache). 40 Fed. Reg. 17847.

[9] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Apache trout (Oncorhynchus apache) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Pinetop, Az. 8 pp.

Bayou darter (Etheostoma rubrum)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 9/25/1975 | Recovery plan: 7/10/1990 |

Range: MS(b) ---

SUMMARY

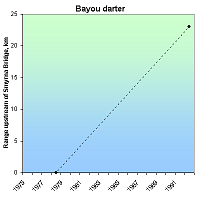

The Bayou darter, endemic to the Bayou Pierre area in Mississippi, is threatened by habitat loss and degradation due to floodplain and channel modification, agriculture, gravel mining, and oil exploration and transport. Neither historic nor recent population estimates are available for the Bayou darter, but a range expansion within Bayou Pierre has been documented over the past 30 years.

RECOVERY TREND

The Bayou darter (Etheostoma rubrum) is endemic to Bayou Pierre and the lower reaches of the tributaries of White OakCreek, Foster Creek and Turkey Creek in Mississippi [1]. It is a habitat specialist, requiring swift, shallow riffles or runs over coarse gravel and pebble [2]. The extent and quality of habitat appear to be related to headcutting.

The darter is threatned by habit degration caused by erosion and siltation, gravel mining, clearing of riparian vegetation with subsequent cultivation to the riverbank, road and bridge construction, and transmission line construction and maintenance [1,5].

Neither historic nor recent population estimates are available [4]. Darter population density, however, remained stable between 1986 and 1988 [2] and between 1986 and 1994 [2].

The darter's range has increased over the last 30 years. From 1963 through 1975, the Bayou darter reached its upstream limit in Bayou Pierre 7.5 kilometers downstream of the Smyrna Bridge [2]. In 1977 and 1978, it was present but uncommon at the Smyrna Bridge and only abundant at the confluence of White Oak Creek and Bayou Piere [2]. In 1993 and 1994 it was common 2 to 3 kilometers upstream of Smyrna Bridge ( in 1992, a single fish was collected 23 kilometers upstream) [2].

The Bayou darter has continued to occupy its downstream-most location (at or near the confluence of Bayou Pierre and Little Bayou Pierre) [3, 4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990. Bayou Darter Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jackson, Mississippi. 25 pp.

[2] Ross, S. T., M. T. O'Connell, D. M. Patrick, C. A. Latorre, W. T. Slack, J. G. Knight, and S. D. Wilkins. 2001. Stream erosion and densities of Etheostoma rubrum (Percidae) and associated riffle-inhabiting fishes: biotic stability in a variable habitat. Copeia 2001:916-927

[3] Slack, W.T, S.T. Ross and J.A. Ewing, III. 2004. Ecology and population structure of the bayou darter, Etheostoma rubrum: disjunct riffle habitats and downstream transport of larvae. Environmental Biology of Fishes 71:151–164

[4] Stephen Ross, Eco-Consulting Services, personal communication, 8/15/2005.

[5] NatureServe. 2010. Bayou Darter Species Profile. Available at: http://natureserve.org/.

Big Bend gambusia (Gambusia gaigei)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/19/1984 |

Range: TX(b) ---

SUMMARY

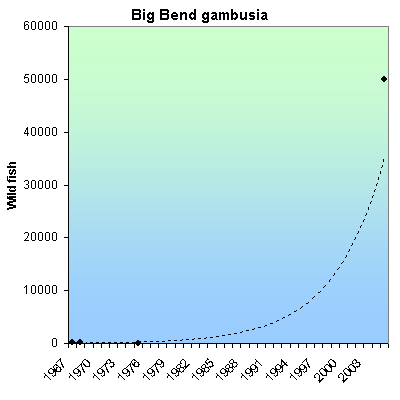

The Big Bend gambusia was once completely extirpated from the wild by water diversions and exotic fish introductions. Reintroduced from three survivors in 1957, the total wild population grew to about 50,000 by 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

The Big Bend gambusia (Gambusia gaigei) historically occurred in the outflow of warm water springs in what is now Big Bend National Park. Boquilla Spring and Spring 4 (Graham Ranch Springs) were definitely occupied; Spring 1 may have been as well [1]. The Boquilla Spring population was extirpated when flows ceased in 1954. Flows were later restored, but contamination with western mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) continues to make Boquilla Spring uninhabitable. The Spring 4 population crashed between 1954 and 1956, and was extirpated by 1960 due to contamination by western mosquito fish and the diversion of flows to provide drinking water and a fishing pool for the Rio Grande Village Campground in 1954. Predation by the introduced green sunfish may have been a factor as well. Today the species occurs in three intensely managed, artificial spring areas within Big Bend National Park and in two captive populations (Dexter National Fish Hatchery and University of Texas at Austin).

During an unsuccessful 1956 effort to eradicate western mosquito fish from Spring 4, Big Bend gambusia were relocated to other waters within Big Bend National Park and to the University of Texas [1]. The park relocations failed, but the three University of Texas fish (two males and one female) survived. In 1957 they were returned to an artificial refugia specifically constructed for them within the park. The population thrived until 1960 when it was contaminated with western mosquito fish. At that time, 15 fish were relocated to the University of Texas, and 20 were relocated to a newly constructed refugia near the Rio Grande Village Campground. The new refugium was supplied by water from Spring 1. In 1968, the refugium was found to be contaminated with green sunfish [3]. The population of 250 fish was removed, the refugia drained and restored, and about 100 fish were reintroduced [5]. In the winter of 1975, nearly all fish in the refugia died (probably due to excessively cold water). The population was augmented the following year with fish from the University of Texas. A drainage ditch was created in 1976 to better regulate water temperatures. In 1978, the species was introduced into the ditch where it continues to thrive today. The third existing population was created by the 1984 reintroduction of fish to the Spring 4 outflow and stenothermal spring waters 50 meters to the southwest [2]. These populations have thrived, reaching approximately 50,000 fish in 2005 [4]. The University of Texas at Austin has maintained a captive population since 1956. The Dexter National Fish Hatchery population was established in 1974. It initially suffered die-offs due to periods of cold water, but has since been stabilized by temperature regulation efforts [1].

Though Big Bend gambusia conservation efforts date back to the 1950s, the park's chief biologist credits the Endangered Species Act with prompting the successful, systematic efforts to conserve the species habitat [3]. Continuing threats include water contamination, sedimentation from flooding, reduction in spring flows and introduction of western mosquito fish and green sunfish via floods or humans.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Big Bend gambusia (Gambusia gaigei) Recovery Plan. U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, NM.

[2] Hubbs, C.L., G. Hoddenbach and C.M. Fleming. 1986. An enigmatic population of Gambusia gaigei. Southwestern Naturalist 31:121-123.

[3] Wauer, R. 1997. For All Seasons, A Big Bend Journal. Austin (University of Texas Press).

[4] Clark Hubbs. 2005. Personal communication with Clark Hubbs, Professor emeritus, School of Environmental Science, University of Texas, September 7, 2005.

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/15/1992 |

Range: NV(b) ---

SUMMARY

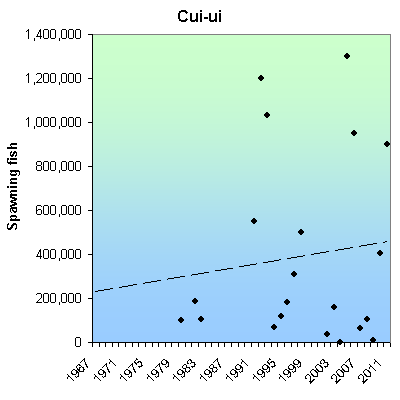

The Cui-ui, a fish found only in Pyramid Lake, Nev., declined due to agricultural diversions that led to a drop in lake levels. Though habitat, fish passage, water level management have improved, the cui-cui remains threatened by drought and diversions. Listed as endangered in 1967, the cui-ui increased from about 100,000 spawning adults in 1983 to more than 900,000 in 2011. Annual rates, however, are highly variable.

RECOVERY TREND

The Cui-ui (Chasmistes cuius) is a sucker fish which formerly inhabitated Pyramid and Winnemucca lakes in Nevada. Adult and juvenile fish inhabitat the lake year-round, but adults leave the lake annually to spawn in its feeder streams.

The Cui-ui was extirpated from Winnemucca Lake in the 1930s when a drought and excessive water diversions completely dried the lake, killing all the fish [1].

Cui-ui populations in Pyramid Lake began to decline after the construction of Derby Dam in 1905 and following the establishment of the Newlands Reclamation Project that led to subsequent agricultural diversions from the Truckee River [2]. Approximately one-half of the annual flow of the Truckee was typically diverted in the early to mid-1900s [3]. Due to decreased flows, Pyramid Lake dropped about 25 meters in surface elevation by 1970 [3]. This drop in lake levels resulted in the formation of a sand-bar delta at the mouth of the Truckee River that essentially blocked the cui-ui from ascending the river to reach their spawning grounds except for in occasional high flow years [2].

In addition, increasing agricultural, municipal, and industrial water demands altered the volume and timing of river flows, and channelization, grazing, and timber harvesting in and along the Truckee River reduced riparian canopy and increased bank erosion [1]. Industrial and agricultural pollutants from point and nonpoint sources along the river also began to affect water quality.

Stampede Dam and Reservoir (completed in 1970) and Marble Bluff Dam (completed in 1976) have helped control river flow and volume and have enhanced spawning runs [1]. Marble Bluff Dam has created several miles of habitat suitable for cui-ui spawning immediately upstream [1]. The regulation of water flows in combination with restrictions on the harvest of cui-ui, hatchery programs (currently run by the Paiute tribe), and the installation of a fishway at Marble Bluff Dam that can be used to give fish access to the river in low-water years have led to increasing cui-ui numbers [3]. In addition, as a result of better water management, in 1987 a band of cottonwoods and willows became established along the Truckee bank [3]. This resulted in changes in channel and floodplain morphology that, along with increased shade from riparian vegetation, improved aquatic conditions for the cui-ui [3].

Between 1950 and 1979, cui-ui only twice had significant successful reproduction, causing the species to have two major year classes during this period [4]. It avoided extinction only through longevity as it can live up to 50 years [4]. This allowed the cui-ui to persist over decades with minimal reproduction.

Cui-cui spawning levels are highly variable (over 1,000,000 spawners in 1992, 1993, and 2005; less than 40,000 in 2002, 2004, 2009) but increased significantly since 1967 and have continued to increase since 1980:

Average Number of Spawning Cui-ui, 1980-2011 [4, 5, 8, 9, 10]

1980-1984 130,157

1985-1989

1990-1994 711,500

1995-1999 276,750

2000-2004 65,723

2005-2009 485,400

2010-2011 651,500

The Dave Koch Cui-ui Hatchery continues to produce large numbers of cui-ui juveniles used to enhance populations [2]. It is unclear, however, how many of these juveniles make it into the adult population and hatchery efforts have begun to focus more on extended rearing [1].

In 2002, the management regime for flows supporting the cui-ui was changed from an annual release to allow spawning, to year-round management to benefit the ecosystem [7]. This resulted in a better-defined channel and other improvements that now allow spawning to occur every year, and contributed to record spawning that occurred in 2005.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Cui-ui (Chasmistes cujus) Recovery Plan. Second revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. 47pp.

[2] Pyramid Lake Fisheries. 2000. Dave Koch Cui-ui Hatchery website. http://www.pyramidlakefisheries.org/Cui-ui.htm

[3] Rood, S.B., C.R. Gourley, E.M. Ammon, L.G. Heki, J. R. Klotz, M.L. Morrison, D. Mosley, G.G. Scoppettone, S. Swanson, and P.L. Wagner. 2003. Flows for Floodplain Forests: A successful riparian restoration BioScience 53(7):647-656.

[4] Scoppetone, G.G. and P.H. Rissler. 1995. The endangered Cui-ui of Pyramid Lake, Nevada in Our Living Resources, A report to the Nation on the distribution, abundance and health of U.S. plants, animals, and ecosystems. National Biological Service. Available online at http://web.archive.org/web/20060925013929/http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/r250.htm.

[5] DeLong, J. 2011. With cui-ui thriving, the whole river teems. Reno Gazette-Journal, May 30, 2011. www.pyramidlake.us/images/news/2011news/5-30-11%20RGJ%20Cui-ui%20Run%20Article.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2011.

[6] Scoppetone, G.G. and P.H. Rissler. 2007. Effects of Population Increase on Cui-ui Growth and Maturation. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 136:331–340.

[7] Heki, L. 2011. Personal communication regarding population, spawning and flow management.

[8] Scoppettone, G., M. Coleman and G.A. Wedemeyer. 1986. Life history and status of the endangered cui-ui of Pyramid Lake, Nevada. Fish and Wildlife Research 1, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 23 pp. www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA323249

[9] U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2011. Cui-ui Spawning Runs. Website maintained at http://www.usbr.gov/projects/Project.jsp?proj_Name=Washoe%20Project

Gila trout (Oncorhynchus gilae gilae)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/10/2003 |

Range: AZ(b), NM(b) ---

SUMMARY

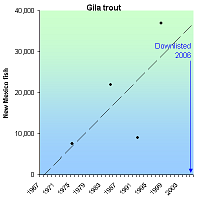

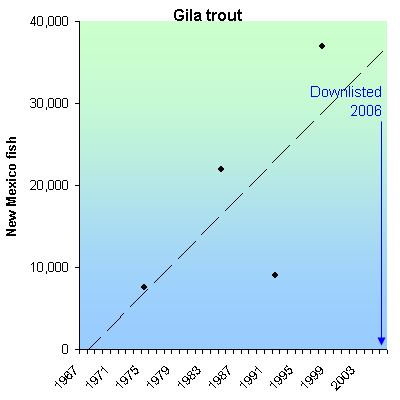

The Gila trout was extirpated from most of its range by habitat loss and competition and hybridization with exotic fish species, most notably rainbow and brown trout. By 1950 it had been reduced to about 20 stream miles. It was listed endangered in 1973. The New Mexico population grew from about 7,600 in 1975 to 37,000 in 2008. The total number of populations increased from five in 1975 to fourteen in 2003. It was downlisted to "threatened" status in 2006 and has since been reintroduced to Arizona.

RECOVERY TREND

The Gila trout (Oncorhynchus gilae gilae) had an historic range that included the headwaters of the Gila River drainage in New Mexico, the Gila River, and possibly the San Francisco River drainage, and the Verde and Agua Fria drainages of Arizona [1]. By the time the species was formerly described in 1950, its distribution had been dramatically reduced to as few as 20 stream miles [1].

Historic declines in Gila trout populations were associated with habitat degradation and competition and hybridization with exotic fish species, most notably rainbow and brown trout [1]. Mining, logging, and cattle-grazing activities altered habitat through increased erosion and sedimentation as well as by causing changes in water levels, increased water temperatures, and reduced bank cover [1]. Overfishing was also problematic [1]. Forest fires (that now burn more severely than they did historically) and associated fire suppression activities also pose a threat to Gila trout populations [1].

A survey conducted in 1975 (two years after the Gila trout was listed as endangered under the current Endangered Species Act) found that five relict populations remained [1] and estimated the population at less than 7,600 fish [2]. These five populations (Main Diamond Creek, South Diamond Creek, McKenna Creek, Spruce Creek and Iron Creek) were restricted to headwater stream habitats in the upper Gila River drainage in New Mexico [1]

In 1985, the total Gila trout population was estimated to have increased to between 18,000 and 26,000 [3]. By 1987, recovery and reintroduction efforts had resulted in the establishment of Gila trout populations at nine localities (eight in New Mexico and one in Arizona) and the USFWS proposed downlisting the species [4]. Shortly after this proposal however, a flood eliminated more than 80 percent of the Gila trout population from McKnight Creek (a reintroduced population), a forest fire and subsequent flooding eliminated the Main Diamond Creek population (this population was ultimately saved through the removal and subsequent repatriation of trout), and drought and forest fire eliminated more than 90 percent of the South Diamond Creek population [4]. This demonstrated the fragility of the species status and in 1991 the downlisting proposal was withdrawn [4]. In 1992, a sixth relict population in Whiskey Creek was discovered [1], but despite this, total population size was estimated to be less than 10,000 [2]. In 1996 and 1997, two of the relict populations (McKenna and Iron Creek) were found to have hybridized with rainbow trout, reducing the number of genetically pure relict populations to four [5].

Continuing captive propagation and reintroduction efforts, aimed not only at increasing population numbers but also at preserving and replicating genetic lineages at new locations [5], resulted in increasing Gila trout numbers through the 1990s. By 1998 the total wild population had increased to around 37,000 [2]. By 2003 there were 14 populations of Gila trout in the wild that inhabited approximately 65 miles of habitat [1]. The four pure relict populations are self-sustaining in the wild [1] and three of these four (Main Diamond, South Diamond, and Spruce creeks) are replicated at least once [5]. Replicated populations in New Mexico are now reproducing in the wild [5]. The Mora National Fish Health and Technology Center maintains a captive population of Gila trout that represents the Main Diamond lineage [1].

It was downlisted from "endangered" to "threatened" in 2006, and the rule to downlist includes a special rule that allows some recreational fishing of the species [8].

Although populations have increased since listing, threats to the Gila trout still exist and over the past decade, declines due to forest fire and hybridization have taken place [6]. Since 1989, seven populations of Gila trout have been extirpated by high-severity wildfires and subsequent flooding and ash-flows; two of these have been reestablished [5]. Grazing, which still occurs on eight of 14 streams occupied by Gila trout, may also adversely affect some populations [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Gila trout recovery plan (third revision). Albuquerque, New Mexico. i-vii + 78 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Region 2 Regional News and Recovery Updates. Endangered Species Bulletin XXVII(2):38.

[3] New Mexico Game and Fish. 2004. Gila Trout Species Account. Biota Information System of New Mexico BISON version 1/2004. Website <http://fwie.fw.vt.edu/states/nmex_main/species/010600.htm> accessed Aprill, 2006.

[4] Platania, S.P. Perils Facing the Gila Trout. Our living resources: a report to the nation on the distribution, abundance, and health of U.S. plants, animals, and ecosystems. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Service, Washington, DC. 530 pp. Available at <http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/sw157.htm>.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Proposed Reclassification of the Gila Trout (Oncorhynchus gilae) from Endangered to Threatened with Regulations. Federal Register 70:24750-24764.

[6] New Mexico Game and Fish. 2004 Biennial Review of threatened and Endangered Species of New Mexico, Final Draft Recommendation. Available at <http://www.wildlife.state.nm.us/conservation/threatened_endangered_species/documents/2004biennial_review_fulltext.pdf>.

[7] Arizona Game and Fish Department. Animal abstract, Gila Trout. Heritage Data Management System. Available at <http://www.azgfd.gov/w_c/edits/documents/Oncogila.fo.pdf>.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Reclassification of the Gila Trout (Oncorhynchus gilae) From Endangered to Threatened. 71 Fed. Reg. 40657.

Mohave tui chub (Gila bicolor mohavensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 9/12/1984 |

Range: CA

SUMMARY

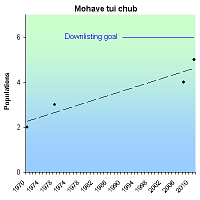

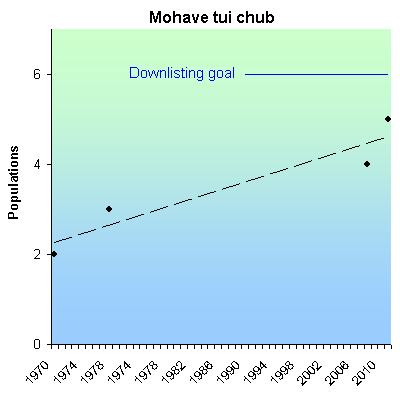

he Mohave tui chub declined to near extinction because of climate change, competition, hybridization and predation by non-native species, water pollution, water withdrawals, habitat loss, and altered flooding regimes. When listed as endangered in 1970, the chub existed in two small populations. Reintroduction programs and intensive habitat creation and protection increased it to 8,500 fish in five large populations in 2012. Six populations are needed for downlisting.

RECOVERY TREND

The Mohave tui chub’s (Gila bicolor mohavensis) recovery from the edge of extinction in 1970, to 8,500 fish in five populations in 2012, is a testament to the Endangered Species Act and decades of hard work by scientists, government agencies, and more recently, visionary high school students who rallied a small town to save the Mojave River’s only native fish. None of that would have been possible though, had the chub not been saved from extinction by two unlikely men: the apocalyptic founder of the Jehovah’s Witnesses and a tax-evading, land-stealing, tonic-selling, radio evangelist/real estate developer dubbed ""King of Quacks"" by the American Medical Association.

BIOGEOGRAPHY

The Mohave tui chub is the only fish native to the Mojave River basin. During the Pleistocene (2.5 million to ~11,700 years ago), it occurred throughout the basin, which at the time was a vast wetland complex comprised of the Mojave River, three very large lakes (Manix, Mojave, and Little Lake Mojave), many small lakes, and a network of meandering channels connecting them [1]. Manix, the largest of the lakes, carved Afton Canyon with its outflow, and from there alternatively flowed into Lake Mojave or Little Lake Mojave [1]. Lake Mojave covered what are now the Soda Lake and Silver Lake playas. Little Mojave Lake covered what are now the East and West Cronese Lake playas.

As the climate warmed during the Holocene (beginning ~11,200 years ago), the basin became increasingly arid. What was largely a lacustrine (=slow-water, wetland) ecosystem, became a fluvial (=relatively swift-water, riverine) ecosystem. The channels and small lakes disappeared; the large lakes shrank to small, ephemerally wet playas, and perennial surface water was confined to the Mojave River and its larger tributaries.

The Mohave tui chub became restricted to the Mojave River mainstem, primarily inhabiting deep pools and slough-like areas: micro-habitats similar to the Pleistocene ecosystem it evolved in [1]. In the early 20th century it was most common in lower elevation, low gradient, perennial reaches downstream of Victorville, Calif. Though stream flow is more reliable in the headwaters upstream of Victorville, the chub is not evolutionarily equipped to establish viable populations in the relatively shallow, swift-flowing, frequent flooding conditions which predominate there.

THREATS AND DECLINE

Human water withdrawals in the modern period greatly exacerbated the natural desertification trend, eliminating most perennial reaches of the river, and confining the chub to a very small range. In the 1930s, nonnative arroyo chubs (used as bait fish) were introduced to the river where they competed and hybridized with the Mohave tui chub [1]. The former’s dominance was facilitated by its better ability to survive flooding. Other detrimental introductions included large-mouth bass, catfish, trout, mosquitofish, bullfrogs and crayfish. These, combined with increased flooding, pollution, water withdrawals and habitat degradation, extirpated non-hybridized Mohave tui chub from the river mainstem by 1970.

The recent discovery of parasitic Asian tapeworms in tui chubs is a concern, but as of 2012 has not been proven to reduce population levels [2]. At least two of the populations—MC Spring (at Soda Springs) and Camp Cady—have reduced genetic diversity [2].

RECENT POPULATION TREND

1970: When listed as an endangered species in October 1970, the Mohave tui chub was extirpated from the Mojave River [1]. It existed in just two populations: Soda Springs and Piute Creek. The 1984 federal recovery plan [1] incorrectly states that it also existed at Paradise Spa and Two Hole Spring (see below).

1978: In 1978, there were three populations [1]. Soda Springs still existed; Piute Creek failed (1977); new populations were established at Lark Seep (1971) and Desert Research Station (1978).

1992: In 1992, there were three populations [4]. Soda Springs and Lark Seep still existed; Desert Research Station failed (1992); a new population was established at Camp Cady (1986).

2008: In 2008, there were four populations [3]. Soda Springs, Lark Seep and Camp Cady still existed; a new population was established at Lewis Center (2008).

2011: In 2011, there were five populations [2]. Soda Springs, Lark Seep, Camp Cady and Lewis Center still existed; a new population was established at Morning Star Mine (2011).

The Mohave tui chub’s total population size in 1970 is not known. We estimate a likely maximum of 1,000 to 2,000 fish based on later trends at Soda Springs and the presumption that the Piute Springs population was never large. The 2011 population was on the order of 8,000 to 9,000 fish [8]. The most recent precise data are: 1,573 fish at Soda Springs (2007), 3,607 at Camp Cady (2007), 6,000 at Lark Seep (2003), 1,560 at Lewis Center (2011), and 1,000 introduced to Morning Star Mine (2011) [6, 9].

RECOVERY TIME AND CRITERIA

The 1984 federal recovery plan requires that to downlist the chub from “endangered” to “threatened,” there must be six populations of at least 500 fish [1]. Each must have been free of threats for at least five years and have survived at least one significant flooding event. Each of the four established populations extant as of 2012 greatly exceeds 500 fish, but only three have been extant for five years. The fifth (Morning Star Mine) also exceeds 500 fish, but it is too early to declare it “established” since it was only established in October 2011.

Recovery efforts increased considerably in response to a 2003 National Park Service sponsored tui chub recovery workshop [4] and plans are underway to increase the size of existing populations and establish new ones [9]. We expect the 1984 downlisting criteria to be met within the next decade. The plan, however, is outdated. A draft revision was completed in 1988 [12], but never finalized. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies contemplated updating the plan in 2003 (see discussion at [4]), but have not yet done so.

Accounting for the chub’s history of sudden, unexpected population failures (see below), we recommend a more fluid, meta-population approach: ten populations at sites dedicated to chub recovery, which over a five-year period simultaneously include at least six populations of at least 1,000 fish. This criterion anticipates and buffers against sharp population declines and complete population failures. It will prevent a single, catastrophic—but temporary—event from triggering the need to uplist again to endangered status.

The recovery plan requires that to be delisted, the tui chub be re-established in the majority of its historic range [1]. The goal is ambiguous, however, because chub’s historic late-Holocene range is different from the historic Pleistocene range in which it evolved, and which still defines its genetically-driven behavior. Restoration to its historic modern range (the Mojave River mainstem), moreover, is almost certainly unattainable due to climate change, dewatering, widespread presence of numerous nonnative species, urbanization, and lack of slough-like habitats to serve as post-flood recolonization refugia (see discussion at [4]). Under the current delisting criteria, we concur with National Park Service biologists who concluded that “Human population growth and increased water demand in the Mojave River drainage may make delisting the Mohave tui chub impossible” [13].

We recommend that the criteria be updated to recognize that while the chub should be restored to the Mojave River to maintain important natural selection pressures, its range there will be considerably less than the majority of the river. Most future Mohave tui chub populations, like all current populations, will exist in human-created ponds adjacent to the river. There should be approximately 20 of these, of which approximately 12 should simultaneously support at least 1,000 fish over a five-year period.

POPULATIONS EXTANT AS OF 2012

1. SODA SPRINGS, MOJAVE NATIONAL PRESERVE

The Soda Springs complex is known to have been occupied by Mohave tui chubs since at least 1917, with strong evidence pointing back to at least 1907 [1]. It may have been continually occupied much longer than that. It contains the sole remaining, non-introduced, relict chub population (MC Springs) which has served as the ultimate source of all reintroduction efforts since the 1950s. Soda Springs is the only existing population that was also extant in 1970 when the chub was listed as an endangered species.

Soda Springs was used for thousands of years by early predecessors of the Mohave and Chemehuevi peoples and was an important site in the traditional range of the Chemehuevi and Vanyume [7, 11]. Being a rare, dependable water source on the well-used trade route between the California Coast and the Colorado River, Soda Springs would have been extensively visited by native groups, but there is no evidence that they harmed the Mohave tui chub (know as “tui-pagwi” to the Paiute) or its habitat there or elsewhere.

The first European to visit Soda Springs was likely Father Francisco Garces in 1776 [11]. Trapper/explorer Jedediah Smith was the first recorded Anglo to visit the springs. He passed through in 1826 and 1827, finding the water “brackish.” Kit Carson and Lt. John C. Fremont led later expeditions. A permanent military post was established at the springs in 1864 to thwart alleged attacks by Mohaves. The post was shuttered in 1871.

The area was mined for gold, salt and soda at the turn of the century [7, 11]. The heavily used Tonopah-Tidewater Railroad was laid north what is now Lake Tuendae in 1906 [7, 11]. The springs were extensively altered and diverted during this time, but effects on the chub were not recorded.

Between 1914 and 1974, Soda Springs was occupied by two quixotic religious groups who unwittingly saved the Mohave tui chub from extinction by keeping it alive, and even increasing its population, until formal conservation programs took over chub’s fate in 1970s.

Charles Taze Russell, the charismatic founder of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, believed that the second coming of Jesus happened in October of 1874 [15]. He would reign invisibly on this earth, harvesting souls in the desert of modernity for 40 years. Then in October of 1914, Christ would re-ascend to Heaven, bringing an end to the Time of the Gentiles, and unleashing Armageddon “with fury poured out; a time of trouble such as never was before, nor ever shall be; a day of wrath” [15]. Russell divined these dates from biblical numerology and corroborated them in a close examination of the geometry of the Great Pyramid of Giza, which he called the “Bible in stone” [16].

Though his Watchtower Bible and Tract Society was headquartered in Brooklyn, N.Y., Russell and a small band of followers homesteaded Soda Springs in 1914 [7, 18] to mine for gold and wait for the end of the world. The outbreak of World War I later that year was a welcome confirmation of the End of Days—“When our worthy President and also his Holiness the Pope requested Christian people to pray God for the cessation of the European war, we declared that the prayer was not in harmony with the Divine arrangement…the war is the one predicted in the Scriptures as associated with the great day of God Almighty-‘the day of vengeance of our God.’”—at Soda Springs, it led to the jailing of Russell’s German immigrant followers and himself with them [18].

Soda Springs was abandoned in 1916 following Russell’s strange death and a massive flood which damaged the railway and inundated much of the area for two years. It remained abandoned, and what would become, if it was not already, the last relict Mohave tui chub population, was left undisturbed until the arrival of radio evangelist Curtis Howe Springer in 1944 [7].

Springer at various times claimed to be a doctor, college dean, ordained minister, and emissary of non-existent colleges, academies and medical schools [19]. He lectured on health, temperance, marriage, the ill-effects of argumentation, and the virtues of Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal. He amassed a fortune selling tonics, teas, bath salts and breads to remedy baldness, cancer, sore toes and hemorrhoids, rejuvenate cells, restore beauty and lengthen life. His most popular concoctions were Hollywood Pep Tonic, Antediluvian Desert Herb Tea, and Mo-Hair.

Leaving a string of lawsuits, investigations and failed resorts behind [20], Springer moved to California in the late 1930s, and in 1944 filed mining claims on 12,800 acres of federal land around Soda Springs [1]. He then built the Zzyzx Mineral Springs and Health Spa with the labor of homeless men bussed in from Los Angeles and given room and board [19]. While Springer later used this “charity” to justify Zzyzx’s tax-exempt status [21], others note that he also took control of the men’s social security checks via the his post office, only doling out cash after charging them for his largess [22].

The sprawling complex included a two-story hotel called The Castle, a church, radio station, private airfield (the Zyport), 60 cabins, mineral baths, and falsely advertised “hot” springs. The name Zzyzx was chosen so the enterprise could be marketed as the “last word in health.”

Springer gave sermons twice daily over loud-speakers hidden in the rocks and used the power of his internationally syndicated radio show to draw thousands of people to his Christian health spa [19].

Meanwhile, by 1955, the Mohave tui chub was on its last legs. It was on the verge of extirpation from its entire native habitat in the Mojave River. The last remaining native population lived in the tiny 9-meters-by-9-meters MC Spring on Springer’s resort where it had miraculously survived his introduction of development, wandering tourists, water diversions and sermons. Had this population been lost, the chub would almost certainly be extinct today.

That year, however, Springer created the centerpiece of Zzyzx resort: Lake Tuendae, a 1.4-acre, palm-tree-lined oasis arrived at by the freshly constructed two-lane Boulevard of Dreams [7]. Fed by the “Enrico Caruso Fountain,” the pond was a healing bath for guests and allegedly the source of the salts in Mo-Hair, which he sold to guests and his radio congregation as a cure for baldness. For reasons unknown, Springer transplanted tui chub from MC Spring to the lake, accidentally carrying out the most important action in the history of Mohave tui chub conservation: replicating the world’s last remaining relict population.

The chub thrived in its new habitat, which has since become one of the species’ largest, most stable populations. All tui chub populations created since 1955, and all populations in existence today, were ultimately sourced from Lake Tuendae as the MC Spring population is too small to support translocations [1, 3, 9].

Springer’s empire was expanding as well. His sermons were now broadcast on 221 U.S. and 102 foreign radio stations, his health remedies were selling rapidly, and his income swelled with the sale of land parcels at the edge of Zzyzx, promising to create a permanent Christian community in need of his services [19].

In the late 1960s, it all began to unravel when a civil suit was filed alleging that Mo-Hair did not increase hirsuteness. Singer had been sued over his remedies many times, but this one drew the attention of the American Medical Association and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The former had been following Singer since 1929 and 1935 declared him “a person with an ignorance of the human body and its processes that is wide and deep, who by virtue of an unblushing effrontery, combined with a flair for garrulity, dupes an ignorant public” [20]. Now in 1969, it proclaimed him the “King of Quacks” [21]. The latter prosecuted him for false advertising. The Internal Revenue Service began an investigation, and most calamitously, the Bureau of Land Management sought not only to stop the land sales, but to seize the entirety of Zzyzx, alleging that Singer had illegally taken public lands as his own by filing false mining claims.

Years of court battles ensued. In the end, the self-described “last of the old-time medicine men” [21] was sentenced to 60 days in jail (he served 41) and Zzyzx was returned to the public domain in 1974 [1, 7]. In 1994, it became part of the Mojave National Preserve.

The Soda Springs wetland complex consists of three nearby subpopulations:

- MC Spring (=Mohave Chub Spring): MC Springs is the only existing relict population and, via its replication in Lake Tuendae, has served as the founding source of all currently existing populations [4]. At three meters in diameter, it is the smallest subpopulation at Soda Springs, supporting just 20 to 60 small fish in 1981-1982 [1].

- Lake Tuendae: Lake Tuendae was excavated in 1955 by Curtis Howe Springer [1]. Measuring 150 meters by 40 meters (1.4 acres), it has a maximum depth of 3.3 feet and is maintained by pumping from the Zzyzx Well. It was populated with Mohave tui chub from MC Springs shortly after 1955.

- Three Bats Pond (also called West Pond). Three Bats Pond is a 60-meter-by-70-meter water-filled mine shaft that was enlarged by Springer, probably to create the appearance he was mining as required by his mining claims [7]. It is fed by a natural spring and possibly a second spring and groundwater seepage. Heavy pumping from the Zzyzx Well reduces water levels in Three Bats Pond.

Because it experiences greater water quality extremes, Three Bat’s tui chubs are smaller than Lake Tuendae’s. A fish kill occurred in 1981, possibly due to high pH, low dissolved oxygen, and/or ammonia toxicity [1] and the entire population was lost in 1984 due to poor water quality [7].

2. LARK SEEP, CHINA LAKE NAVAL AIR WEAPONS STATIONS

Lark Seep is a perennial wetland created in 1945 by discharge from the City of Ridgecrest’s wastewater treatment plant [4]. The G1 Channel, G1 Seep, George Channel and North Channel were later dug to carry water from Lark Seep farther away from the facility.

In 1971, 425 Mohave tui chubs were transplanted from MC Spring to Lark Seep [4]. An additional 75 fish were transplanted in 1976 [1]. The chub has since been established in G1 Channel, G1 Seep, George Channel and North Channel [4].

In 1984, it was the species’ largest population [1].

3. CAMP CADY STATE WILDLIFE AREA

In 1986, the California Department of Fish and Game excavated two small ponds in the Camp Cady State Wildlife Area and introduced Mohave tui chubs [4]. The ponds are fed from a water pump. They each supported approximately 500 fish.

In 1991, the east pond was drained and lined with plastic to solve a seepage problem [4]. In 2003, the east pond dried up because the property caretaker became ill and neglected it. There is only one pond at Camp Cady now, maintained by Fish and Game volunteers.

4. LEWIS CENTER, ACADEMY OF ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE

The Lewis Center, Academy of Academic Excellence is a K-12 charter school in Apple Valley, Calif. straddling the Mojave River [4]. It manages 138 acres of its 150-acre campus for wildlife.

In 2004, Molly Estes and Amanda Pearson, two students at the Academy, attended a National Park Service-sponsored workshop on recovery of the Mohave tui chub [4]. They began a project which in 2008 resulted in 548 tui chub from Lark Seep being introduced to the Deppe Pond and Tui Slough refuges on the Mojave River Campus of the Lewis Center [5]. A drainage pond between the school and the Mojave River, Deppe Pond was drained, expanded, reshaped, and lined by students, Boy Scouts, volunteers and community members. Tui Slough was excavated by students, Boy Scouts and volunteers. By 2011, the two pond population had grown to 1,560 fish [6].

5. MORNING STAR MINE, MOHAVE NATIONAL PRESERVE

In October 2011, 1,000 tui chub from Lark Seep and Soda Spring were introduced to the Morning Star Mine in the Mohave National Preserve [8]. The 1-acre, groundwater fed site is an abandoned mining pit.

POPULATIONS ELIMINATED AFTER 1970 LISTING

* PARADISE SPA

In 1967, the Bureau of Land Management and the California Department of Fish and Game introduced 50 tui chubs from Soda Spring to Paradise Spa, an artificial pond south of Las Vegas in Clark County, Nev. [1, 10]. The population failed “a few years” later [1]. We can find no record of the failure year, only that it was not present in 1981 [10]. As there is no evidence that it was viable or even extant in late 1970, we do not regard it as post-1970 elimination. It is included here because it was reported as being extant at the time of listing in the 1984 federal recovery plan [1].

* TWO HOLE SPRING

On Aug. 20, 1970—two months before the tui chub was listed as an endangered species—41 fish were introduced to Two Hole Spring, but the population did not become established and was absent in June 1971 [10]. On July 9, 1971, 150 additional fish were reintroduced, but also failed to establish and were missing by July 21, 1971 [10]. Because it was never established, we do not regard it as post-1970 elimination. It is included here because it was reported as being extant at the time of listing in the 1984 federal recovery plan [1].

1. PIUTE SPRINGS

On Dec. 18-19, 1969, 150 fish were introduced to Piute Springs at the base of Piute Wash on Bureau of Land Management land northwest of Needles, Calif. [10, 14]. The wash is subject to flash flooding. Fish were not present in the winter of 1970 following a flood and the population was feared to have been eliminated [14]. It is unknown whether the population survived and/or additional introductions were made, but it was present in 1976 and eliminated by 1978 [10].

2. SOUTH COAST BOTANICAL GARDEN

On Jan. 27, 1970, 147 fish were introduced to the South Coast Botanical Garden. The pond was drained by 1972 (after the fish were relocated elsewhere) [10]. Fifty-five fish were introduced later that year, and were augmented with 105 fish in 1975. None were present in 1976.

3. DOS PALMAS SPRINGS

On May 25, 1972, 100 fish were introduced to Dos Palmas Springs, but were absent by 1980 [10].

4. LION COUNTRY SAFARI PONDS

On June 1, 1972 and March 28, 1975, 822 fish were introduced to Lion Country Safari Ponds [10]. The population was present in January 1974 but absent by November 1977.

5. EATON CANYON NATURE CENTER

On June 5, 1972, 20 fish were introduced to the Eaton Canyon Nature Center [10]. The population later failed [1].

6. BUSCH GARDENS

On June 27, 1972, 49 fish were introduced to Busch Gardens [10]. The population later failed [1].

7. DESERT DISCOVERY CENTER

Sixty chubs were placed in a 300-gallon display tank at the Bureau of Land Management’s Desert Discovery Center (then called the Barstow Way Station) on July 22, 1975 [1]. The population was augmented on July 1, 1981. In 1984, the population size was 50 to 60 fish. The population died around 1995 when maintenance of the tank stopped [4]. Because of its small size, display use and vulnerability to extinction, it was never classified as a conservation population by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [1].

8. DESERT RESEARCH STATION

This 30-meter-by-30-meter pond near Hinckley, Calif. was established with 16 introduced fish on Dec. 12, 1978 [1]. It was augmented with 126 fish from Soda Springs in 1981 and 56 fish from Lark Seep in 1986 [1, 4]. In 1984, the population size was 2,000 to 4,000 [1]. The population died in 1992 when the Barstow Unified School District closed the facility [4].

9. LAKE NORCONIAN

On Feb. 8, 1978, an unknown number of fish were introduced to Lake Norconian, but the population had failed by February 1980 [10].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Recovery Plan for the Mohave Tui Chub, Gila bicolor mohavensis. Portland. Oregon, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[2] Dudek and ICF International. 2012. Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) Baseline Biology Report (March 2012 draft). Prepared for the California Energy Commission, Sacramento, California. Available at http://www.drecp.org/documents/baseline_biology_report/10_Appendix_B_Species_Profiles/10c_Fish/Mohave%20tui%20chub.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Mohave tui chub (Gila bicolor mohavensis = Siphaletes bicolor mohavensis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Available at https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2392.pdf

[4] Hughson, D. and D. Woo. 2004. Report on a Workshop to Revisit the Mohave Tui Chub Recovery Plan and a Management Action Plan. Available at http://www.nps.gov/moja/naturescience/upload/ACF46F1.pdf

[5] The Lewis Center. Wish for a Fish webpage http://www.lewiscenter.org/Local-Programs/Mohave-Tui-Chub/index.php Accessed April 14, 2012

[6] The Lewis Center. Working with Mohave tui chub. Web page: http://lcermtcrefugia.blogspot.com/ Accessed April 14, 2012

[7] Woo, D. and D. Hughson. 2004. Zzyzx Mineral Springs- Cultural Treasure and Endangered Species Aquarium. Pages 84-87 in Harmon, D., B. M. Kilgore, and G. E. Vietzke, eds. Protecting Our Diverse Heritage: The Role of Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites. (Proceedings of the 2003 George Wright Society / National Park Service Joint Conference.) Hancock, Michigan: The George Wright Society, 2004. Available at http://www.georgewright.org/0320woo.pdf

[8] Grunwald, L. 2011. The endangered Mohave tui chub has a new home courtesy of Ventura FWO and others. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, FieldNotes Entry, November 16, 2011. Available at http://www.fws.gov/FieldNotes/regmap.cfm?arskey=31046

[9] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Intra-Service Biological Opinion for Establishing Additional Populations of Mohave tui Chubs in the Mojave Desert in California (8-8-11-FW-22). August 26, 2011. Available at http://www.dmg.gov/documents/20110826_MEMO_BO_Mohave_Tui_Chub_U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.pdf

[10] Hoover, F. and J. A. St. Amant. 1983. Results of Mohave chub, Gila bicolor mohavensis, relations in California and Nevada. California Fish and Game 69(1):54-56. Available at http://hegel.lewiscenter.org/users/mhuffine/subprojects/Student%20Led%20Research/chubworld/pdfs/hoover.pdf

[11] U.S. National Park Service. 2001. Environmental Assessment: Dredging of Lake Tuendae, Habitat for the Endangered Mohave tui chub (Gila bicolor mohavensis). Available at http://www.dmg.gov/documents/EA_Drdgng_Lake_Tuendae_Habitat_for_the_MTC_NPS_121709.pdf

[12] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1988. Revised Recovery Plan for the Mohave Tui Chub Gila bicolor mohavensis. Available at http://hegel.lewiscenter.org/users/mhuffine/subprojects/Student%20Led%20Research/chubworld/pdfs/hoover.pdf

[13] Wullschleger, J., D. Hughson, and D. Woo. 2004. Recovering the Mohave tui chub. Natural Resource Year in Review – 2004. U.S. National Park Service. Available at http://www.nature.nps.gov/YearInReview/yir2004/03_M.html

[14] St. Amant, J. A. and S. Sasaki, 1971. Progress Report on Reestablishment of the Mohave Chub, Gila Mohavensis. Calif. Dept. of Fish and Game Vol. 57, pp. 307-308. Available at http://cluster.biodiversitylibrary.org/c/californiafishga57_4cali/californiafishga57_4cali_djvu.txt

[15] Russell, C.T. 1876. “Gentile Times: When do they end?” The Bible Examiner, Vol. XXI, No.1, October, 1876. Available at http://www.strictlygenteel.co.uk/examiner/examiner.html; Barbour, N.H. and C.T. Russell. 1877. Three Worlds and the Harvest of this World. Rochester, NY. Available at http://www.strictlygenteel.co.uk/threeworlds/threeworldstitle.html

[16] Russell, C.T. 1898. “Corroborative Testimony of God’s Stone Witness and Prophet: The Great Pyramid in Egypt. Box Ten in Thy Kingdom Come. Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, Brooklyn, NY. Available at http://www.strictlygenteel.co.uk/kingdomcome/study10.html

[17] Russell, C. T. 1915. “View form the Watch Tower” Zion’s Watch Tower 36(1), January 1, 1915. Available at http://www.mostholyfaith.com/bible/Reprints/Z1915JAN.asp

[18] Jaeger, E.C. 1958. “Live on a Mojave Playa” Desert Magazine 21(2):24-26, February, 1958. available at http://mydesertmagazine.com/files/195802-DesertMagazine-1958-February.pdf

[19] Wikipedia. Curtis Howe Springer. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_Howe_Springer. accessed April 15, 2012.

[20] Bureau of Investigation 1935. ""Bureau of Investigation: Curtis Howe Springer - A Quack and His Nostrums.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 105(11): 900-902, September 14, 1935. Available at http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/105/11/900.full.pdf

[21] Rasmussen, C. 2002. Zzyzx: An Unlikely Home of Hucksterism and Miracle Cures. Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2002. Available at http://articles.latimes.com/2002/jun/16/local/me-then16

[22] Hays, L. 2005. Pilgrims in the Desert: The Early History of the East Mojave Desert and Baker, California. Mojave Historical Society.

Okaloosa darter (Etheostoma okaloosae)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/4/1973 | Recovery plan: 10/26/1998 |

Range: FL

SUMMARY

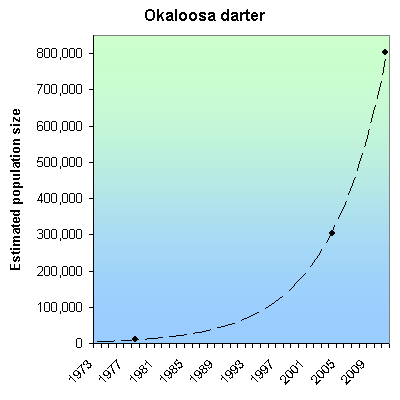

Its restricted range has been reduced by habitat modification and subsequent increases in the brown darter population, habitat degradation due to erosion, and water impoundment [1]. The darter's exact, historic, and current population level is unknown. 1978 estimates ranged from 1,500 to 10,000. The population size doubled between 1995 to 2010, reaching 802,668 fish in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The endangered Okaloosa darter occurs in only six stream systems, which are located in Okaloosa and Walton Counties, Florida [1]. Much of there range is located on Elgin Air Force Base who the FWS has partnered with and worked in conjunction with for the recovery of the darter.

The darter's historic population level is unknown. In 1978 estimates ranged from 1,500 to 10,000 darters [1]. The numbers declined throughout the 1980’s and mid 1990’s, and have stabilized or increased since, however lost stretches of stream have not been regained [2].

Eglin AFB is implementing an effective habitat restoration program to control erosion from roads, borrow pits (areas where materials like sand or gravel are removed for use at another location), and cleared test ranges [3]. Since 1995, Eglin AFB has restored 317 sites covering 484.8 acres that were eroding into Okaloosa darter streams [3]. All 38 borrow pits within Okaloosa darter drainages are now stabilized (146.5 ac) [4]. The other 279 sites (338.3 ac) [4] included in the total area are characterized as non-point sources (pollution created from larger processes and not from one concentrated point source, like excess sediment from a construction site washing into a stream after a rain) of stream sedimentation [3]. Eglin AFB estimates that these efforts have reduced soil loss from roughly 69,000 tons per year in darter watersheds in 1994, to approximately 2,500 tons per year in 2010 [3]. As of 2006, Eglin AFB had completed about 95 percent of the erosion control projects identified for the darter watershed [3]. Restoration activities began earlier in the Boggy Bayou drainages. Accordingly, darter numbers increased in the Boggy Bayou drainages earlier than in the Rocky Bayou drainages [3]. Increases in darter numbers over the past 10 years generally track the cumulative area restored during that timeframe [3].

Of the 153 road crossings of Okaloosa Darter drainages, 57 have been eliminated by Elgin AFB, most of these were likely barriers to fish passage and/or problems for stream channel stability and removing them has improved habitat and reduced population fragmentation [4].

In FY 2007, Eglin AFB restored portions of Mill Creek within the Falcon and Eagle golf course[3]. Staff from Eglin Natural Resources, the Eglin golf course, and the Service determined that it was feasible to restore all impoundments upstream of Plew Lake, the largest impoundment on the system, to free- flowing streams and to remove all but one of the culverts that convey the stream underneath fairways on the golf course [3]. Present in the smallest of the six darter watersheds, the darter population in Mill Creek is probably most vulnerable to extirpation [3]. Within one year of completion, Okaloosa darters had colonized the entire restoration project and recruitment had been observed [3]. We anticipate that restoration at Mill Creek will help maintain a viable population in the Mill Creek system [3].

In 2009, a partnership including Eglin AFB, the Service, FWC, and MBBA initiated a restoration of Anderson Pond and the adjacent campground and recreation area [3]. As part of this project, the impoundment was removed, and over 1000 meters of stream channel were constructed [3]. A new pond was excavated in a portion of the original impoundment to accommodate fishing and other recreational activities [3]. This project has reconnected darters isolated in the headwater reaches of Anderson Branch with the Turkey Creek population and re-established habitat for an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 darters [3]. Both the Mill Creek and Anderson Pond projects accomplished stream restoration while promoting outdoor recreation and education opportunities for the public [3].

More extensive surveys were began in 1995 and continued through 2010, during which period darter density increased from 25/20 meters to over 50/20 meters [5]. The total species population in 2011 was estimated to be 802,668 [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Okaloosa Darter (Etheostoma okaloosae) Recovery Plan (Revised). Atlanta, Georgia. 42pp.

[2] Howard L Jelks. 2001. Monitoring of the endangered Okaloosa darter (Etheostoma okaloosae) population on Eglin Air Force Base. (SIS# 1987).

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Reclassification of the Okaloosa Darter From Endangered to Threatened and Special Rule. 76 FR 18087

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Okaloosa Darter 5-year Review: Summary & Evaluation

[5] Frank Jordan and Howard Jelks. 2011. Population trend figure provided by correspondence with Karen Harringoton.

Oregon chub (Oregonichthys crameri)

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 3/10/2010 | Listed: 10/18/1993 | Recovery plan: 9/3/1998 |

Range: OR

SUMMARY

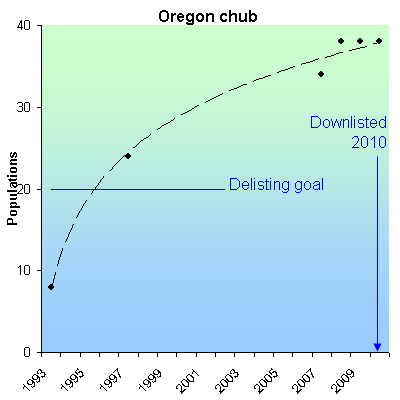

The Oregon chub became endangered when its slackwater habitat was destroyed by dams, channelization and agriculture. It continues to be threatened by predaceous non-native fish and population isolation. When listed as an endangered species in 1993, just eight populations remained. By 2008 there were 38, 11 of which were reintroduced. In 2010 was downlisted to threatened and provided with a federally protected critical habitat area.

RECOVERY TREND

The Oregon chub (Oregonichthys crameri) is a small minnow found only in the Willamette River basin in western Oregon [1]. Historically it occurred throughout the basin from Oregon City to Oakridge in sluggish habitats off main river channels such as beaver ponds, oxbows, stable backwater sloughs and flooded marshes with little or no water flow. Chub prefer habitats with silty and organic substrate, an abundance of aquatic vegetation, and cover for hiding and spawning.

Much of the chub's habitat was destroyed by changes in seasonal flows after the building of dams throughout the Willamette basin, channelization of the Willamette River and its tributaries, and poor agricultural practices. Combined with the introduction of predacious nonnative fish, habitat loss caused Oregon chub numbers to plummet, leading to its listing as an endangered species and designation of federally protected critical habitat in 1993 [1].

Conservation efforts have focused on establishing new chub populations in habitats free of predatory nonnative fish [1, 2]. By 2010, 11 populations had been successfully established by reintroductions. These populations, however, are isolated, causing the chub to remain at risk of genetic bottlenecking.

Between 1993 and 2008, the number of known populations increased from 8 to 38 (=475%), with 15 supporting at least 500 fish and being stable or increasing for five years (2002-2007) [1, 2]. This exceeded the chub's downlisting criteria of 10 stable or increasing populations of at least 500 fish, leading to its reclassification from "endangered" to "threatened" in 2010 [2].

The 1998 Oregon chub federal recovery plan stipulates that for the chub to be declared recovered, there must be 20 stable or increasing populations (measured over seven years) of at least 500 fish, with at least four located in each of the three sub-basins (Mainstem Willamette, Middle Fork Willamette and Santiam) [3]. The 20 populations must be protected in perpetuity.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Oregon chub (Oregonichthys crameri) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation. Portland Fish and Wildlife Office. 34 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Reclassification of the Oregon Chub From Endangered to Threatened, Final Rule. 75 Fed. Reg. 21179.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Oregon Chub (Oregonichthys crameri) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

Owens pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/30/1998 |

Range: CA

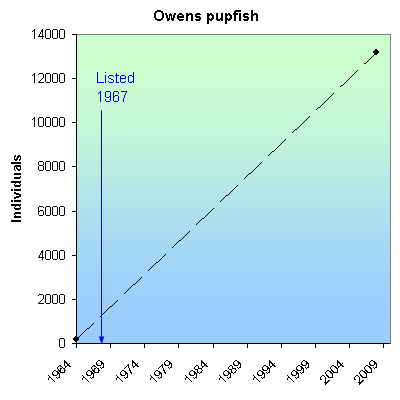

SUMMARY

The Owens pupfish was pushed to the brink of extinction by water diversion and believed extinct by 1942 until it was rediscovered in 1964; the species was protected as endangered in 1967. Current threats are invasive vegetation and fish and stochastic events. A single population of 200 fish was rediscovered in 1964. Following protection in 1967, new populations were established. As of 2008 there were four populations and an estimated total of up to 13,200 fish.

RECOVERY TREND

The Owens pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus) is a small fish that is about 2.5 inches long and is only found in the Owens Valley portion of the Owens River in Mono and Inyo counties, Calif. Males are bright blue and become brighter during the spring and summer mating season; females are dusky olive-green. Owens pupfish congregate in small schools and feed mostly on aquatic insects. Females may be involved in spawning acts up to 200 times per day, laying one to eggs at a time in spring and summer. They live for one to three years [1].

Owens pupfish were once widespread along the Owens River, occurring in clear

waters of springs, sloughs and marshes along the river from Fish Slough in Mono County south to Lone Pine in Inyo County [1]. The fish were so numerous that the native Paiute tribe captured large numbers of pupfish with basket-like nets and dried them for use as winter food [2]. The species was believed to be extinct by 1942, because of water diversions, until a small population of about 200 individuals was discovered in Fish Slough in 1964. The Owens pupfish was protected as an endangered species in 1967.

Endangered Species Act protection led to the establishment of new populations and aggressive management actions to reduce threats to the fish.

The rediscovered population was nearly lost to predation by introduced fishes. In 1969 Phil Phister captured the remaining individuals, and for a brief time the world’s total population of the species was held in two buckets while Phister and his colleagues worked to build a barrier and remove the invasive fish species that were preying on the pupfish. Phister succeeded in saving the pupfish.

As of 2008 there were four populations of this species: Fish Slough, Mule Springs, Warm Springs and Well 368. Progress is also being made toward establishing two new pupfish populations [2]. The population has increased from around 200 fish at the time of listing to an estimated population of 1,500 to 13,200 fish as of 2008 [2].

The Fish Slough population is made up of three subpopulations: The BLM Springs sub-population, which supported an estimated 1,000 to 10,000 fish in 2008 and is ranked as increasing; the BLM Ponds subpopulation, which supported 100 fish in 2008 and is ranked as stable; and the Marvin’s Marsh subpopulation, which supported 100 to 1,000 fish in 2008 and is ranked as declining.

The Warm Springs population supported fewer than 100 fish in 2008 and is ranked as increasing. The Mule Springs population supported 100 to 1,000 fish in 2008 and is ranked as stable. The Well 368 population contained 100 to 1,000 fish in 2008 and is ranked as stable.

Ongoing threats to the Owens pupfish include habitat encroachment by aquatic vegetation, predation by nonnative species, and stochastic factors such as random weather events and genetic effects from small population size.

CITATIONS

[1]. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Owens Basin wetland and aquatic species

recovery plan, Inyo and Mono Counties, Calif. Portland, Ore. pp. 18-113.

[2]. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Owens Pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus)

5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Ventura, Calif. 21 pp.

Pahrump poolfish (Empetrichthys latos)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 3/17/1980 |

Range: NV(b) ---

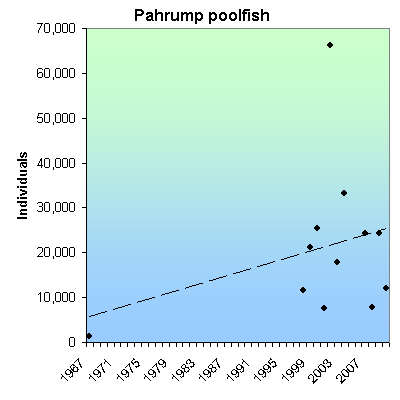

SUMMARY

The Pahrump poolfish is endemic to Manse Spring, Nevada, but was removed when the spring began to dry up. It is threatened by water pumping, water pollution, vandalism, exotic species, and being dependent upon human pool maintenance. It was listed as an endangered species 1967. In 1971 only 29 fish remained. New populations were created, managament was improved and between 2007 and 2010, the population averaged 17,145 fish.

RECOVERY TREND

The Pahrump poolfish (Empetrichthys latos latos) is the only surviving member of the Empetrichthys genus—a group of four desert fish evolved to live in isolated Nevada springs. It is now the only existing fish native to the Pahrump Valley.

- The Ash Meadows poolfish (E. merriami) was endemic to a group of large springs in Ash Meadows. It went extinct in 1950 due to the introduction of exotic species and possibly excessive water pumping [5, 6].

- The Raycraft Ranch poolfish (E. l. concavus) formerly occurred at Raycraft Ranch Spring, in Pahrump Valley. Its population was suppressed by the introduction of exotic predatory carp (Cyprinus spp.) and groundwater pumping [5, 6]. Excessive pumping eventually destroyed the spring's commercial value, leaving it as a perceived source of bothersome mosquitoes. It was thus filled with dirt and completely destroyed in 1957.

- The Pahrump Ranch poolfish (E. l. pahrump) formerly occurred at two springs on Pahrump Ranch in Pahrump Valley. Its population was suppressed by the introduction of exotic predatory carp (Cyprinus spp.) and desiccation of the springs from groundwater pumping [4, 5, 6]. The springs dried up in 1958 due to irrigation pumping.

The Pahrump poolfish is endemic to Manse Spring in the Pahrump Valley. In 1962 or 1963, the pool became contaminated with non-native goldfish, suppressing the poolfish [7, 8]. Water pumping for agriculture had lowered the spring's flow rate. In light of these threats and the recent extinction of all other members of the genus, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service placed the Pahrump poolfish on the nation's first list of endangered species in 1967. It was one of only 19 fish on the original list of 72 endangered species.

Goldfish were removed from Manse Spring later that year, but were not eradicated [7, 8]. The poolfish population was estimated at 1,300.

In 1968, two young professors who would go on to become the deans of desert fish ecology—Jim Deacon of the University of Nevada and the W. L. Minckley of Arizona State University—published a remarkable essay in response to the 1967 endangered species list. Entitled "Southwestern fishes and the enigma of 'endangered species'," the essay briefly assessed the status of numerous desert fish and described the challenges facing the scientific community in the new task of determining which fish deserve the status of an "endangered species." [7].

Summing up the state of desert fish and what was needed to save them, Deacon and Minckley wrote:

"A great natural experiment of evolution, evolution, also amplified and perhaps accelerated by isolation in desert aquatic habitats appears about to become an exercise in extinction, if man will have it so…Possibly the most compelling reason for preserving species is the value such a program has in demonstrating the importance of restraint. An "endangered species" program is imperative, not only for the sake of the species studied, but also because of what it can teach us about the possibilities for continued survival of other species, including man."

They cataloged many extinctions and concluded that the next in line was the Pahrump poolfish due to the "catastrophic practice" of water mining the Pahrump Valley. Showing that the flow rate of Manse Spring had declined from 6.0 ft2/second in 1875 to 1.5 ft2/second in 1966, they grimly predicted that "withdrawal of nearly 41,000 acre-feet annually virtually guarantees continued decline of the water table, eventual failure of Manse Spring and extinction of the last population of the genus Empetrichthys…in less than 10 years."

Seven years later, right on schedule, Manse Spring ran dry, killing off the last natural population of the Pahrump poolfish and ending several million years of Empetrichthys evolution in its natural habitat [2].

The Pahrump poolfish, however, did not go extinct.

In response to the Deacon/Minckley essay, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife and others moved fish from Manse Spring to Los Latos Pool in 1970, to Corn Creek Springs in 1971, and to Shoshone Ponds in 1972. The Los Latos Pool population failed in 1976 or 1977. Corn Creek Springs and Shoshone Ponds were successful and still existed as of 2012. A third population was successfully established at Spring Mountains Ranch State Park in 1983 and still existed as of 2012.

DOWNLISTNG CONSIDERATION

The 1980 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan requires the establishment of three populations more than 500 fish for three consecutive years in order to downlist the Pahrump poolfish to threatened status [4]. Delisting can occur if the populations remain at 500 adults for three additional years after downlisting [4]. The habitat of the three populations must also be secured [4].

In 1993, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a downlisting proposal because the species had more than 500 individuals at Corn Creek Springs, Shoshone Ponds and Spring Mountains Ranch from 1986 through 1993 [4]. From 1988 to 1993 the populations at each site contained “far greater than 500 individuals" [4]. The habitat was deemed sufficiently secure because the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had applied for vested water rights at Corn Creek Springs, the Nevada Department of Wildlife had State appropriative water rights at Shoshone Ponds, and the Nevada Division of State Parks had appropriated water rights for Sandstone Spring, the water source for the Spring Mountain Ranch irrigation impoundment [4].

The proposal was not finalized and in 2004, the agency withdrew it due to the sudden loss of the Corn Creek population, a 2003 population decline at Shoshone Ponds, and concern that the state would not protect its water right at Spring Mountains Ranch State Park [1].

STATUS OF POPULATIONS

LOS LATOS POOL

Los Latos Pool is a pond in southern Nevada along the Colorado River near Lake Mohave. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Reclamation and the Nevada Fish and Game moved "a few fish" from Manse Spring to Los Latos Pool in June, 1970 [2, 10]. "Some" fish were still present in the summer of 1976. In the fall of 1976, several storms struck the area, moving debris in to the pool. The Pahrump poolfish extirpated between then and the next survey in 1977 and has not inhabited the pool since [2, 3]. No further reintroductions were conducted because the site was deemed to have limited recovery potential [2].

CORN CREEK SPRINGS

Corn Creek Springs is a complex of three ponds on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Desert National Wildlife Range north of Las Vegas. Water enters the upper pond from two springs, overflows in a middle pond, and then drains into the lower pond [2]. The Pahrump poolfish was established there in August, 1971 with 29 fish from Manse Spring [2, 10]. It thrived until at least 1993, with greater than 500 fish occupying the springs in all years between 1986 and 1993, and far greater than 500 fish from 1988 to 1993 [1, 3, 5].

Bullfrogs and crayfish were illegally introduced to the springs after 1993, causing the population to plummet to three in 1998 and to be extirpated in 1999.

Two small, tamper-proof tanks were constructed in 2002 and 120 poolfish were transplanted there in 2003. The population has remained viable since then, with about 159 fish being present in 2010 [5].

The small size of the tanks renders them incapable of supporting a population numbering in the thousands as used to exist at Corn Creek Springs. It likely renders them incapable of even supporting a consistent population of more than 500 fish, thus preventing the Pahrump poolfish from meeting its downlisting or delisting goal (see above). For this reason, the Nevada Department of Wildlife recommended in 2005 that the poolfish be reintroduced to the Corn Creek Springs [3].

SHOSHONE PONDS

Shoshone Ponds is a series of three, small, constructed artesian well-fed pools (North Pond, Middle Pond, and Stock Tank), one large spring-fed stock pool, and one artesian well outflow. It is on BLM land approximately 60 kilometers southeast of Ely, White Pine County, Nevada [10]. In 1970 the Bureau of Land Management designated the Shoshone Ponds and 1,240 surrounding acres as the Shoshone Ponds Natural Area.

Sixteen Pahrump poolfish from Manse Spring were introduced to Shoshone Ponds in March, 1972 [3, 10]. The population was lost in 1974 when vandals turned off a valve controlling flow are artesian water to the springs [3].

The water system was modified to make it more secure and in 1976, 50 fish from Corn Creek Springs (after spending a year in the University of Nevada at Las Vegas' holding facility) were reintroduced [10].

From 1986 to 1993, more than 500 fish occupied the springs in all years; far greater than 500 fish were present from 1988 to 1993 [1, 3, 9]. With the exception of 2002 when the population soared to 8,149 fish and 2003 when it plummet to 922 fish, the population was stable between 3,000 and 5,600 fish between 1997 and 2004. In 2010, the population was estimated at 4,527 fish [9].

SPRING MOUNTAINS RANCH STATE PARK

Spring Mountains Ranch State Park is in western Clark County, Nevada. In 1983, exotic fish were eradicated from pools there, and 426 poolfish were introduced from Corn Creek Springs [3].

More than 500 fish were present between 1986 and 1993. Population estimates were 24,800 fish in 1989, 16,775 in 2003 and 29,876 in 2004. In 2007 there were approximately 20,000 fish, in 2008 there were approximately 5,000, in 2009 there were approximately 20,000, and in 2010 the population was estimated at 7,400 [9].

Chimney Springs and Hot Creek, Nye County

The U.S.G.S. refers to the existence of stable Pahrump poolfish population at this location 1992 [11], but we can find no other reference too it and presume it is a mistake.

Sodaville Springs, Mineral County

The U.S.G.S. refers to the existence of stable Pahrump poolfish population at this location 1992 [11], but we can find no other reference too it and presume it is a mistake.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1980. Pahrump Killifish Recovery Plan. Available at http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/060628.pdf

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Proposed reclassification of the Pahrump Poolfish (Empetrichthys latos latos) from endangered to threatened status. September 22, 1993 (58 FR 49279). Available at http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr2411.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Withdrawal of proposed rule to reclassify the Pahrump Poolfish (Empetrichthys latos) from endangered to threatened status. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, April 2, 2004 (69 FR 173830)

[4] Sada, D. W. and G. L. Vinyard. 2002. Anthropogenic changes in biogeography of Great Basin aquatic biota. Pages 277-294 IN Great Basin Aquatic Systems History (R. Hershler, D. B. Madsen and D. R. Currey eds. 2002. Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences 33.