Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/23/1998 |

Range: AK(s), CA(s), FL(o), HI(s), ME(o), MD(o), MA(o), NH(o), NY(o), NC(o), OR(m), RI(o), SC(o), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

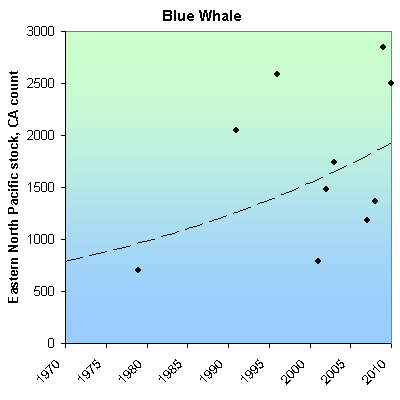

The blue whale population was reduced by as much as 99 percent due to whaling that occurred before the mid-1960s. The number of whales reported off the coast of California, the largest stock in U.S. waters, increased from 704 in 1980 to an estimated 2,497 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal ever known to have lived on Earth [1]. Blue whales are found in all oceans worldwide and are separated into populations from the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere [1]. Each population is composed of several stocks that typically migrate between higher-latitude summer feeding grounds and lower-latitude wintering areas. The largest numbers of blue whales in U.S. waters are within the eastern North Pacific stock. Other U.S. stocks occur in waters off the coast of Hawaii and the Northeast [1].

Pre-whaling blue whale populations had about 350,000 individuals [3]. In 1868, the invention of the exploding harpoon gun made the hunting of blue whales possible and in 1900, whalers began to focus on blue whales and continued until the mid 1960s [1, 3]. During this time, it is estimated that whalers killed up to 99 percent of blue whale populations [3]. Currently, there are about 5,000-10,000 blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere and about 3,000-4,000 in the Northern Hemisphere [3]. Current threats include collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced zooplankton production due to habitat degradation, and disturbance from low-frequency noise [1]. The offshore driftnet gillnet fishery is the only fishery likely to take blue whales, but few mortalities or serious injuries have been observed [2].

EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

The Eastern North Pacific Stock feeds in waters off the coast of California from June to November and then migrates south to Mexico (sometimes going as far south as Costa Rica) in winter/spring [2]. Recently, blue whales seen off the coast of Alaska were photo-matched to photos from the Southern California area, indicating that California animals now migrate as far north as Alaska [4]. This is probably a reestablishment of a traditional migratory route [4]. The number of whales reported off the coast of California increased from 704 in 1979/80 to 2497 in 2010 [2, 11]. It is not certain if the overall increasing trend indicates a growth in the size of the stock, or just increased use of California waters [2], but in general, the stock is thought to have increased [1]. Because this is the largest stock in U.S. waters, it dominates the trend of the species in U.S. waters.

WESTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

Blue whales feeding along the Aleutian Islands are probably part of a central western North Pacific stock that is thought to migrate to offshore waters north of Hawaii in winter [5]. Sightings of blue whales in Hawaiian waters are infrequent, although acoustic recordings indicate that blue whales occur there. There are no estimates of population size for this stock [5]. No blue whales were sighted during aerial surveys of Hawaiian waters conducted from 1993 to 1998 or during shipboard surveys conducted in the summer/fall of 2002 [5]. In 2004, three blue whales were seen in the western Aleutians, the first U.S. sightings of blue whales from this western North Pacific population in several decades [6]

NORTH ATLANTIC STOCK

The blue whale is an occasional visitor along the Atlantic coast of the Northeast [7]. Sightings of blue whales off Cape Cod, Mass., in summer and fall may represent the southern limit of the feeding range of the western North Atlantic stock that feeds primarily off the Canadian coast [7]. Blue whales have been sighted as far south as Florida, however, and the actual southern limit of this stock’s range is unknown [7]. Because blue whales are not frequently seen in U.S. Atlantic waters, there are insufficient data to determine the stock's population trend [7]. In 1997, the total number of photo-identified individuals for eastern Canada and New England was 352 [1].

CITATIONS

[1] NMFS. 1998. Recovery plan for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Prepared by Reeves R.R., P.J. Clapham, R.L. Brownell, Jr., and G.K. Silber for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 42 pp.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] American Cetacean Society. 2005 American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Website http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bluewhl.htm (accessed on 11/30/05).

[4] NOAA. Fisheries. 2004. NOAA Scientists Sight Blue Whales in Alaska. Press Release 7/27/2004.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[6] Rankin, Barlow and Stafford. (in press) Marine Mammal Science.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2002. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised Jan. 2002. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2007. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2008. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] NOAA Fisheries. 2009. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[11] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 7/30/2010 |

Range: AL(o), AK(s), CA(s), CT(s), DE(s), FL(s), GA(s), HI(s), LA(o), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(o), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), OR(s), PA(s), RI(s), SC(s), TX(o), VA(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

Fin whales were hunted in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century, causing population decline. Ongoing threats include illegal and legal whaling, vessel collisions, fishing gear entanglement, reduced prey and noise. Total population size is unknown, but both the North Atlantic and North Pacific populations increased between 1995 and 2009.

RECOVERY TREND

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and southern oceans mix rarely, if at all. For management purposes, the North Pacific is divided into three stocks: 1) the California/Oregon/Washington stock, 2) the Hawaii stock and 3) the Alaska stock [2]. A western North Atlantic stock inhabits U.S. waters along northeastern coasts [3]. Most groups are thought to migrate seasonally, in some cases over large distances [1]. They feed at high latitudes in summer and move to low latitudes in winter. Some groups move over shorter distances and may be resident to areas with a year-round supply of adequate prey.

Fin whales were hunted, often intensively, in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century [1]. From 1947 to 1987, approximately 46,000 fin whales were taken from the North Pacific [2]. Commercial whaling did not end until 1976 in the North Pacific and 1987 in the North Atlantic. The current status of fin whale populations relative to pre-whaling levels is uncertain.

In the North Pacific, pre-whaling populations were estimated to be between 42,000 and 45,000 [2]. By 1973, the North Pacific population is thought to have been reduced to 13,620-18,680 — less than 38 percent of historic carrying capacity [2].

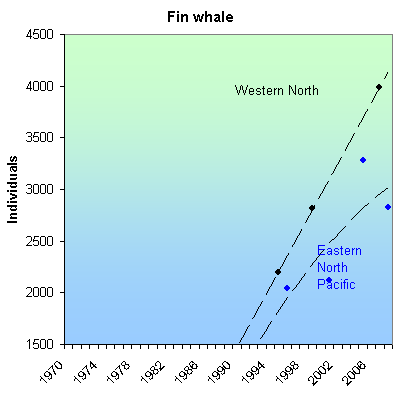

California/Oregon/Washington Stock

The California/Oregon/Washington stock of the North Pacific is thought to be increasing [5]. Fin whale acoustic signals are detected year-round off Northern California, Oregon and Washington, with a concentration of vocal activity between September and February [2]. Fin whales increased in abundance along the California coast between 1979 and 1996, and based on ship surveys in 2001, they continued to increase. Populations appeared to be increasing monotonically from 1991 to 2001 [5]. In 2001, 3,279 (CV= 0.31) were estimated in California, Oregon and Washington coastal waters [2]. The 2008 population was estimated at 2,825 whales [9].

Alaskan Stock

Since 1999, information on abundance of fin whales in Alaskan waters has improved and although the full range has not yet been surveyed, a rough estimate of the size of the population west of the Kenai Peninsula is 5,703 [6]. Surveys conducted in 1999 and 2000 in the central-eastern Bering Sea and southeastern Bering Sea provided provisional estimates of 3,368 (CV = 0.29) and 683 (CV = 0.32), respectively [6]. One aggregation of fin whales spotted in 1999 involved more than 100 animals [6]. Because historical abundance information is lacking, population trends are difficult to determine [6].

Hawaiian Stock

Fin whales are rare in Hawaiian waters and the stock is thought to be quite small [7]. Over the course of 12 aerial surveys conducted within about 25 nautical miles of the main Hawaiian Islands in 1993-98, only one fin whale was sighted [7]. More recent acoustic data suggest that fin whales migrate into Hawaiian waters mainly in fall and winter [7]. In 2002, a ship survey of the entire Hawaiian Islands resulted in an abundance estimate of 174 (CV=0.72) fin whales [7].

Western North Atlantic Population

Western North Atlantic fin whales off the eastern U.S. coast north to Nova Scotia and the southeastern coast of Newfoundland are considered a single stock [3]. New England waters represent a major feeding ground, and calving is thought to take place along mid-Atlantic U.S. latitudes from October to January. The locations used for calving, mating and wintering for most of the population remains unknown. It is likely that fin whales occurring in the U.S. Atlantic undergo migrations into Canadian waters, open-ocean areas, and perhaps even subtropical or tropical regions. An abundance of 2,200 (CV=0.24) fin whales was estimated from a 1995 line-transect sighting survey that covered waters from Virginia to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. A 1999 estimate of 2,814 (CV=0.21) fin whales, currently considered the best estimate for the western North Atlantic stock, was derived from a line-transect sighting covering waters from Georges Bank to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence [3]. The best estimate of population for this stock in 2007 is 3,985 whales [8]. Although there is little data on population trends, the minimum population estimate reported in NOAA Fisheries Stock Assessment Reports has steadily increased since 1992.

The main direct threat to fin whales today is the possibility of illegal whaling or a resumption of legal whaling [1]. In 2006, Japan announced that it would expand hunts to include fin whales [4]. It expected to harvest 10 fin whales from Antarctic waters [4]. Collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced prey abundance due to overfishing and habitat degradation, as well as disturbance from low frequency noise, are also potential threats [1]. The offshore drift gillnet fishery is the main fishery likely to take fin whales [2].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1998. Draft Recovery Plan for the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Sei Whale (Balaenoptera Borealis). Silver Spring, MD.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis): Western Stock revised Dec., 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic stock. Revised Dec. 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[4] Hans Greimel, Associated Press. 2005. Japan To Double Usual Whale Kill in New Antarctic Hunt, Expanded To Include Fin Whales. Nov. 9, 2005.

[5] Barlow, J. 2003. Preliminary Estimates of the Abundance of Cetaceans along the U.S. West Coast: 1991-2001 Southwest Fisheries Science Center Administrative Report LJ-03-03. Available at <http://swfsc.nmfs.noaa.gov/prd/PROGRAMS/CMMP/default.htm>.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Northeast Pacific stock. Revised 10/21/2004.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Draft Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Hawaiian stock. Revised 3/15/2005.

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised 11/2010.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2011. 2010 Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): California/Oregon/Washington stock. Revised 1/15/2011.

Hawaiian common moorhen (`alae `ula) (Gallinula chloropus sandvicensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

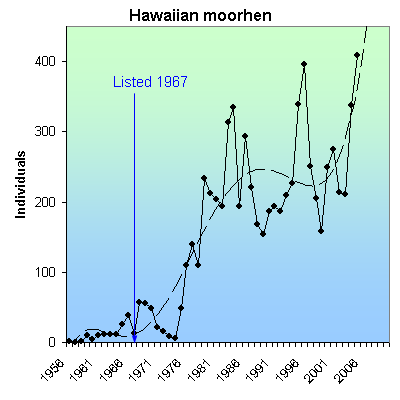

SUMMARY

The Hawaiian common moorhen declined due to destruction and degradation of its wetland habitat. Though absolute abundance numbers are not clear, the species growth rate was sharply positive from 1956 through the mid-to-late 1980s, then increased more slowly through 2007.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus sandvicensis) was common on the main Hawaiian islands except Lana`I and Kaho`olawe in the late 19th century. By the late 1940s it was described as "precarious," especially on Oahu, Molokai, and Maui [1]. The Molakai population was extirpated after the 1940s, reintroduced in 1982, but did not persist and is currently absent from the island [1]. The spread of aquaculture on Oahu and Kauai in the late 1970's and the 1980's likely benefited the species. Aquaculture projects currently support some of the highest concentrations of moorhens in the state [1].

The population was estimated at no more than 57 in the 1950s and 1960s [2] and about 750 in 1985 (500 on Kauai, 250 on Oahu, and a small number on Molokai) [3], but this may be an underestimate [2]. The accuracy of these estimates is unclear because the species is very secretive and not conducive to standard waterbird census methods. Annual winter waterbird counts between 1956 and 2007, however, show a sharp, statistically significant increase through the mid-to-late 1980s, then a slower increase through 2005 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Draft of Second Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. 155 pp.

[2] Engilis, A., Jr., and T. K. Pratt. 1993. Status and population trends of Hawaii's native waterbirds, 1977-1987. Wilson Bull. 105:142-158

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Recovery Plan for the Hawaiian Waterbirds. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

[4] Reed, J. M., C. S. Elphick, E.N. Leno, and A.F. Zuur. 2011. Long-term population trends of endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. Popul Ecol (2011) 53:473–481.

Hawaiian coot (`alae ke`oke`o) (Fulica alai)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

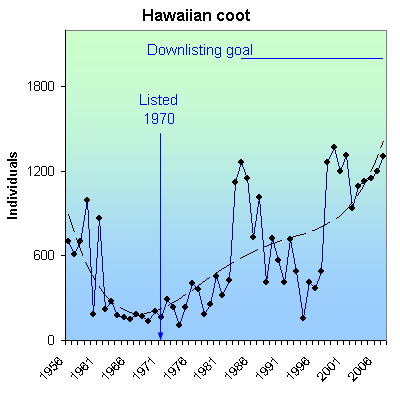

SUMMARY

The Hawaiian coot was initially threatened by hunting in the first half of the last century, but is now threatened primarily by loss of habitat. The Hawaiian coot has increased from 1,000 birds on an extinction trajectory in the 1960's to over 2,000 birds today.

RECOVERY TREND

Hawaiian coots (Fulica alai) historically occurred on all of the main Hawaiian Islands except Lana'i and Kaho`olawe, which lacked suitable wetland habitat [1]. They are known to have been most numerous on Kaua'i, Maui and O'ahu, but there are no historical population estimates. The population was low enough in 1939 to warrant establishment of a permanent hunting ban [2]. In the 1950s the coot was considered to be on a trajectory towards extinction. Fewer than 1,000 birds were thought to remain by the late 1960s.

Hunting was a significant threat until outlawed in 1939 [2]. Habitat loss is now the primary cause of endangerment. For example, Ka‘elepulu Pond on O‘ahu, supported nearly 1,000 coots until it was dredged and surrounded by mowed lawns and cement in the 1940s as part of the Enchanted Lake subdivision [2]. The current population is much smaller. Conversely, the species has expanded into unusual habitats such as sewage-treatment plants at Kailua-Kona, Hawaii; Lana‘i City, Lana‘i; and Kuilima, O‘ahu [2].

Biannual surveys indicate short-term population fluctuations associated with rainfall [1]. The 2005 population was estimated at about 2,100 birds with 80 percent of birds on Kaua’i, O'ahu and Maui. All the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho`olawe are currently occupied. The 2012 Recovery Plan states that based on the most recent data available (2008), populations have recently fluctuated between approximately 1,500 and 2,800 birds and have averaged 2,000 birds [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Revision. Portland, Oregon. October 28, 2011.

[2] Brisbin, I. L., Jr., H. D. Pratt, and T. B. Mowbray. 2002. American Coot (Fulica americana) and Hawaiian Coot (Fulica alai). In The Birds of North America, No. 697 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[3] Reed, J. M., C. S. Elphick, E.N. Leno, and A.F. Zuur. 2011. Long-term population trends of endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. Popul Ecol (2011) 53:473–481.

Hawaiian duck (koloa maoli) (Anas wyvilliana)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

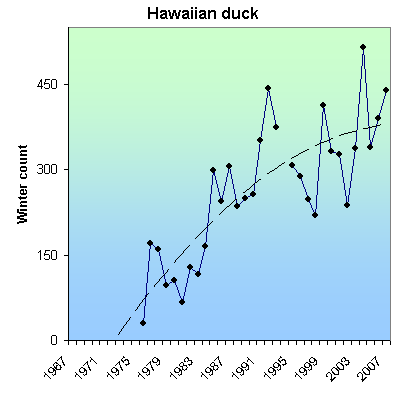

The Hawaiian duck was endangered by hunting, non-native predators, hybridization with domestic ducks, and habitat loss. By 1962, it had been extirpated from all the Hawaiian Islands except Kauai where a few hundred birds remained. In 2002, there were 2,300 birds on Kauai (2,000) and Hawaii (300), and unknown numbers on Oahu and Maui.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian duck (Anas wyvilliana) breeds in montane streams and feeds and loafs in lowland wetlands. It historically occurred on all the main Hawaiian Islands except Lana`i and Kaho`olawe, which have little surface water.

Suitable stream habitats have declined since humans arrived on the islands some 1,600 years ago [1]. Wetlands may have initially increased due to cultivation of taro and rice, but it unknown how duck populations would have responded to the combination of increased wetlands and efforts to keep them from consuming crops. From the late 19th century to fairly recently, wetlands have steadily declined due to development, changes in agriculture practices, and introduced pigs and goats [1].

Hawaiian ducks were also harmed by human hunting, predation of eggs and chicks by introduced rats, mongooses, dogs, cats, fish and birds. Hybridization with feral mallards that escaped from commercial farms established on Oahu in the 1930s and 1940s continues to threaten the species. Hybridization is also a problem on Kaua`i and Hawaii.

The Hawaiian duck was fairly common in the 19th century, but was rare in many places and generally declining in the early 20th century [3]. By 1949 it was extirpated from Maui and Molokai, rarely seen on Hawaii, and reduced to just 500 birds on Kauai, 30 on Oahu, and possibly some birds on Niihau [1]. By 1962 it occurred only on Kauai [3]. The Kauai population declined significantly between 1956 and 1982 [4]. A State of Hawaii captive breeding program reintroduced the species to the Kohala Mountains on the island of Hawaii from 1958 to 1980, resulting in a current population of about 200 birds that utilize stock ponds, streams and the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge [1, 3]. Hybridization is occurring in both high- and low-elevation sites [1].

A total of 326 Hawaiian ducks were reintroduced to Oahu by the state between 1968 and 1980 [3]. The introduction site was occupied by feral mallards, and no mallard-control program was initiated. Most of the current population is believed to be hybridized, with suspected pure birds declining and suspected hybrids increasing in recent years [1]. The state introduced 12 Hawaiian ducks to Maui in 1989 and 1990, but did not control existing mallard populations [1, 3]. There are currently 20-50 birds on the island, mostly at Kanaha Pond, and most, if not all, are hybridized [1, 3].

Biannual summer and winters surveys indicate a population increase between 1967 and 2007, with the Kauai population increasing and others declining due to hybridization [1]. The most recent estimate is from 2002 of 2,200 birds on Kauai (2,000) and Hawaii (200) and unknown numbers of pure birds within the 300 Hawaiian duck-like birds on Oahu and 50 on Maui. [3]. The 2011 federal recovery plan concludes that the population is increasing, but the most recent rangewide estimate is still from 2002 [1].

Kauai supports considerably more birds than all other islands combined due to its having few mongooses and very low levels of hybridization [1]. The species occurs year-round on the Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge and nearby taro fields, though most breeding occurs in montane streams [1]. Use of the refuge increased (first as loafing habitat, later as foraging habitat) due to the creation of impoundments in the 1980s and 1990s and modifications in the late 1990s [1]. The species also uses reservoirs, particularly near Lihu`e and on the Mana Plain [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon.

[2] Engilis, A., Jr. and T.K. Pratt. 1993. Status and population trends of Hawaii’s native waterbirds, 1977-1987. Wilson Bulletin 105:142-158.

[3] Engilis, A., Jr., K.J. Uyehara, and J.G. Giffin. 2002. Hawaiian Duck (Anas wyvilliana). In The Birds of North America, No. 694 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[4] W.E. Banko 1987. Historical synthesis of recent endemic Hawaiian birds. Koloa-Maoli. CPSU/UH Avian history report 12 B-Pt. 1. Univ. of Hawai‘i, Manoa.

Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 9/24/2004 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

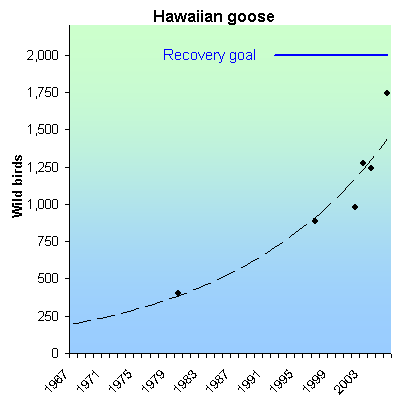

Once numbering more than 20,000 birds, the Hawaiian goose (or “nene”) was reduced to 30 individuals by 1918 due to overhunting, habitat loss and introduced predators. As a result of captive breeding, reintroductions, predator control and habitat protection, it increased from 400 birds in 1980 to 1,744 in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis) or "nene" is Hawaii's state bird. It inhabits shrub and grasslands, and breed and nests on the slopes of volcanoes and some lowland areas [5].

It was once found on most of the larger Hawaiian islands including Kauai, Molokai, Maui and the Big Island and may have numbered in the 20,000s prior to European settlement [1, 3]. As settlers moved onto the islands in the late 1770s, the nene declined due to hunting pressure. The introduction of predatory mongoose in 1883, which preyed on adults, chicks and eggs, further depressed the population [1]. By 1918 only an estimated 30 individuals remained [2].

In the 1950s, captive-breeding programs were initiated in Hawaii and England [2]. These programs eventually released more than 2,300 nenes [2]. In 1967, due to the tenuous state of the remaining population, the nene was listed as an endangered species under the precursor to the Endangered Species Act [4].

Today the Hawaiian goose occurs in the wild on the islands of Hawaii, Maui (reintroduced) and Kauai (reintroduced) [5]. In order to facilitate recovery, the Hawaiian national park system provides supplemental feeding during periodic food shortages [2]. The wild population was estimated at 1,241 individuals in 2004 and 1,744 in 2006 [6].

CITATIONS

[1] The Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust. 2006. Hawaiian Goose General Information. Website <http://www.wwt.org.uk/threatsp/pastwwt/nene.htm> accessed 1/10/06.

[2] National Audubon Society. 2002. Hawaiian Goose. Website <http://audubon2.org/webapp/watchlist/viewSpecies.jsp?id=100> accessed 1/10/06.

[3] NetState. 2006. Hawaii State Bird. Website <http://www.netstate.com/states/symb/birds/hi_nene.htm> accessed 1/10/06.

[4] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hawaiian Goose (Branta sandvicensis) Species Account. Website <http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/life_histories/B00C.html> accessed 1/15/06.

[5] Honolulu Zoo. 2006. Hawaiian Goose (Nene). Website <http://www.honoluluzoo.org/nene_goose.htm; back from brink> accessed January, 2006.

[6] BirdLife International. 2012. Species factsheet: Branta sandvicensis. Website <http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=383> accessed 09/02/2012.

Hawaiian stilt (ae`o) (Himantopus mexicanus knudseni)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/28/2011 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

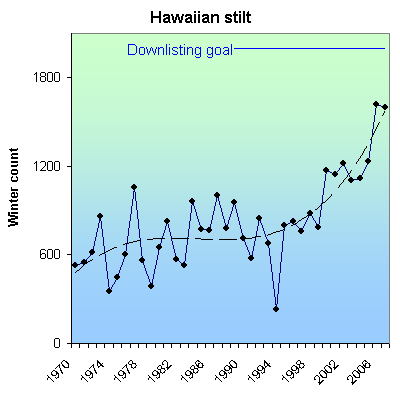

The Hawiian stilt is threatened by habitat loss, predation, and formerly, hunting. It declined to just 200 birds by 1941. The population increased after listing in 1970 and averaged nearly 1,500 birds from 1998-2007.

RECOVERY TREND

The Hawaiian stilt (Himantopus mexicanus knudseni) prefers to nest on freshly exposed mudflats with low growing vegetation. Nesting may occur in fresh or brackish water and in either natural or manmade ponds.

With the exception of Lanai, Ka-ho‘olawe and possibly Hawai‘i, the stilt historically inhabited all the major Hawaiian Islands [7]. As of 2001, they occur on all the main islands except Ka-ho‘olawe. The largest population occurs on O‘ahu, primarily on the north and windward coast at Kahuku Point on James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge, Kahuku Point oyster ponds, Amorient aquaculture ponds, Roland Pond and at Nuupia Ponds in Kaneohe. Smaller populations exist at Pearl Harbor and along the leeward coast. On Kaua‘i, the subspecies is found in large river valleys such as Hanalei, Wailua and Lumahai, on the Mana Plain, and at reservoirs and sugarcane effluent ponds in Lihue and Waimea. On Maui, the largest groups occur on the Kanaha and Kealia coastal wetlands.

Other populations occur in reservoirs and aquaculture areas. On Molokai, birds occur in south coast wetlands and playa lakes. The species colonized Lanai in 1989 where it occurs in Lanai City's wastewater treatment ponds. On the island of Hawaii, the largest populations occur on the Kona coast from Kawaihai Harbor south to Kailua. It also occurs in the Makalawena and Aimakapa ponds, Cyanotech Ponds and Kona wastewater treatment ponds. Smaller populations occur along the Hamakua Coast and in the Kohala River valleys of Waipio, Waimanu and Pololu. Anchialine ponds along the Kona coast provide prime feeding sites.

While no historic population estimates exist, the Hawaiian stilt was formerly quite common. It declined to 200 birds by 1941 due to habitat loss, predation and human hunting, but climbed to about 1,000 birds by 1949, in response to release from hunting pressure [1]. The 1941 estimate has been questioned by some as being too low due to the much higher 1949 estimate, but modeling indicates the species is capable of explosive growth under good conditions [3].

Winter and summer surveys have been conducted since 1956. A review of trends from 1956 to 1989 [4] showed that summer population estimates were more variable on an island basis and were less reliable than winter counts. The statewide summer population count (excluding Kaua'i/Ni'ihau which were not surveyed until 1975) declined significantly from 1968 to 1979, and then increased significantly from 1980 to 1989. The winter counts showed that the Maui population increased significantly from 1956 to 1989, being relatively stable from 1956 to 1971 then increasing from 1972 to 1989. The Moloka'i population increased significantly from 1968 to 1989. The Hawaii population declined significantly from 1968 to 1976, and then increased significantly from 1977 to 1989. The O'ahu population declined significantly from 1956 to 1968, and then increased significantly from 1969 to 1989. The Kaua'i/Ni'ihau population showed no trend between 1975 and 1989 (but the study had little power to detect a trend due to sample size). The statewide population (excluding the Kaua'i/Ni'ihau population) increased significantly between 1968 and 1989.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service corrected errors in past biannual survey data, concluding that the statewide population has increased significantly since 1976 [7]. The recovery plan calls for a stable or increasing population of at least 2,000 for downlisting and delisting. Based on biannual Hawaiian waterbird surveys from 1998 through 2007, the Hawaiian stilt population averaged 1,484 birds, but fluctuated between approximately 1,100 and 2,100 birds [7].

CITATIONS

[1] Robinson, J. A., J. M. Reed, J. P. Skorupa, and L. W. Oring. 1999. Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus meicanus). In The Birds of North America, No. 449 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA

[3] Reed, J.M, C.E. Elphic, and and L.W. Oring. 1998. Life history and viability analysis of the endangered Hawaiian stilt. Biological Conservation 84:35-45

[4] Reed, M.J. and L.W. Oring. 1993. Long-term population trend of the endangered Ae'o (Hawaiian stilt, Himantopus mexicanus knudseni). Transactions of the Western Section of the Wildlife Society 29:1993(54-60).

[5] Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Hawai`i Department of Land and Natural Resources. 1970. Hawaii’s Endangered Waterbirds. Bureau Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Department of Interior, and Hawai`i Division of Fish and Game, Department of Land and Natural Resources. Portland, OR.

[6] Shallenberger, R.J. 1977. An ornithological survey of Hawaiian wetlands. U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Contract DACW 84-77-C-0036, Honolulu, HI. 406 pp.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds, Second Revision. Portland, Oregon. October 28, 2011.

[8] Reed, J.M., C.S. Elphick, E.N. Leno, and A.F. Zuur. 2011. Long-term population trends of endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. Popul Ecol (2011) 53:473–481.

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 11/15/1991 |

Range: AL(o), AK(s), CA(s), CT(s), DE(s), FL(s), GA(s), HI(s), LA(o), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(o), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), OR(s), RI(s), SC(s), TX(o), VA(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

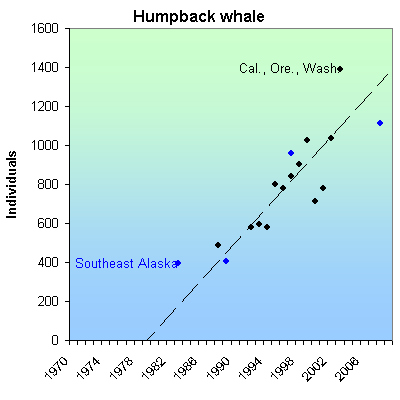

Humpback whale populations were greatly depleted by commercial whaling by the early 1900s. In 1966, the entire North Pacific humpback population was thought to number only around 1,200 animals. As of 2010, the total population of North Pacific humpback was estimated at 21,808.

RECOVERY TREND

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) occur in all oceans of the world, generally inhabiting waters over continental shelves, along continental edges and around some oceanic islands [1]. They winter in warm waters in a few specific locations and mate and give birth on wintering grounds where little feeding is thought to take place [1]. For the summer season, they migrate to high-latitude areas where they tend to stay relatively close to shore (although some groups inhabit deeper water) and spend the majority of their time feeding [1].

Humpback whale populations were greatly depleted by commercial whaling [1]. Prior to whaling, humpback whale numbers are thought to have exceeded 125,000 [1]. American whalers alone killed between 14,164 and 18,212 humpback whales between 1805 and 1909 [1]. Humpback whales first received protection in the North Atlantic in 1955 when the International Whaling Commission placed a prohibition on non-subsistence whaling by member nations [1]. Protection was extended to the North Pacific and southern hemisphere populations following the 1965 hunting season [1]. Although hunting has largely been stopped (some exceptions exist that allow the take of a limited number of whales), and populations appear to be increasing, human impacts such as vessel collisions and entanglements are factors that may be slowing the recovery of the humpback whale population [3].

The total level of human-caused mortality and serious injury is unknown, but data indicate that it is significant [3]. Humpback whales are also vulnerable to marine pollution [2]. The increasing levels of anthropogenic noise in the world’s oceans, such as that produced by certain types of sonar, may also be problematic for whales, particularly for baleen whales that communicate using low-frequency sound [4].

GULF OF MAINE, WESTERN NORTH ATLANTIC STOCK

There are likely six stocks within the western North Atlantic humpback population [3]. A feeding aggregation in the Gulf of Maine (considered a single stock) is the only one U.S. waters [3]. Within New England waters, humpbacks are present in spring, summer and autumn [3]. They spend much of their time feeding and their distribution in this region has been largely correlated to prey species and abundance [3]. In winter, humpbacks from the different western Northern Atlantic feeding areas mate and calve primarily in the West Indies, where spatial and genetic mixing among subpopulations occurs [3]. From late December to early April most of the population is found at Silver and Navidad Banks at the end of the Bahamian archipelago, and along the coast of the Dominican Republic [1]. They are also found at much lower densities throughout the remainder of the Antillean arc, from Puerto Rico to the coast of Venezuela [3]. The only U.S.-controlled portions of the breeding range include waters along the Northwest coast of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. Not all of the stock migrates to the West Indies every winter, however, and significant numbers of animals are found in mid- and high-latitude regions during the winter months [3]. There have recently been a number of wintertime humpback sightings in coastal waters of the southeastern U.S. [3].

North Atlantic humpback numbers are thought to be slowly increasing. An average increase of 1 percent (SE=0.005) was estimated for the period 1979 to 1993 [3]. The best estimate of the number of North Atlantic humpbacks in 1992 and 1993 was 11,570 (CV=0.069) [3]. Data suggest that the Gulf of Maine humpback whale stock is also steadily increasing in size at a rate consistent with the larger population [3]. The Gulf of Maine minimum population was estimated to be 501 in 1992 and 647 in 1999 [3]. Both of these estimates are likely low due to sampling technique [3]. The best estimate of the actual number of animals is thought to be 902 [3].

NORTH PACIFIC

Historic summering range for the North Pacific humpback whales encompassed coastal and inland waters around the Pacific rim from Point Conception, Calif. north to the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea, and west along the Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka Peninsula and into the Sea of Okhotsk [1]. Rough estimates of the pre-whaling population speculate that there were around 15,000 humpbacks in the North Pacific [1]. In 1966, the entire North Pacific humpback population was thought to number only around 1,200 animals [4]. This estimate increased to between 6,000 and 8,000 by 1992 [4]. Although these estimates are uncertain and are based on different methods, the 6 percent to 7 percent growth rate implied is consistent with the observed growth rate of the better-studied eastern North Pacific subpopulation [4].

Although the International Whaling Commission only considered North Pacific humpbacks to be one stock, there is now good evidence for multiple stocks in the North Pacific [4]. There are at least three relatively separate populations that migrate between their respective summer/fall feeding areas and winter/spring calving and mating areas; the eastern North Pacific stock, the central North Pacific stock and the western North Pacific stock [4]. These divisions are a simplification, however, and are not perfect. In general, interchange occurs (at low levels) between breeding areas, although fidelity is extremely high among the feeding areas [4].

The eastern North Pacific stock spend much of their lives within U.S. waters [1]. They winter in coastal Central America and Mexico, migate along the U.S. West Coast, and summer in British Columbia [4]. Mark-recapture population estimates increased steadily from 1988/90 to 1997/98 at about 8 percent per year [4]. Surveys of humpback whale abundance in feeding areas in California, Oregon and Washington conducted from 1991 to 2002 show a steady upward trend with the exception of a large decline in 2000 [5]. The 2002 to 2003 population estimate (1,391, CV=0.22) was higher than any previous estimate and may indicate that the lower numbers in 1999 to 2001 exaggerated any real decline that might have occurred [5]. It could also indicate that a real decline was followed by an influx of new whales from another area [4]. This latter view was substantiated by a greater fraction of new whales seen for the first time in 2003 [4].

The central North Pacific stock, in general, winters around the Hawaiian Islands (some go to Mexico) and migrates to northern British Columbia/Southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound west to Kodiak [6]. Three feeding areas for the Central North Pacific stock have been studied using photo-identification techniques; these include southeastern Alaska, Prince William Sound and Kodiak Island [6]. There has been some exchange of individual whales between these locations, although the aggregation in southeastern Alaska seems to remain relatively isolated from other groups [6]. The current total estimated abundance for this stock is 4,005 individuals [7]. The abundance of the Prince William Sound feeding aggregation is thought to be fewer than 200 whales [6]. In the Kodiak region, 127 individual whales were identified between 1991 and 1994 and abundance was estimated to be 651 (95 percent CI: 356-1,523) [6]. The number of animals in the Southeast Alaska aggregation is thought to have increased [6]. The 2000 estimate of 961 is substantially higher than estimates from the 1980s, which put numbers in the high 300s [6]. In a 2004 report, an annual population rate of increase was calculated to be 10 percent [6]. Another study, based on aerial surveys conducted across the main Hawaiian Islands, and designed specifically to estimate trends in the Central Pacific Stock, found an annual increase of 7 percent from 1993 to 2000 [8]. In 2006, the Southeast Alaska population reached 1,115 [10].

The western North Pacific stock is the least studied of the Northern Pacific populations [9]. This aggregation winters off Japan and probably migrates to waters west of the Kodiak Archipelago (the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands) in summer/fall [9]. Recent surveys in the central-eastern and southeastern Bering Sea in 1999 and 2000 resulted in humpback whale sightings suggesting that the Bering Sea is an important feeding area [9]. New information indicates that humpback whales from the western and Central North Pacific stocks mix on summer feeding grounds in the central Gulf of Alaska and perhaps the Bering Sea [9]. A major research effort (the SPLASH project) was initiated in 2004 in order to better delineate stock structure of humpback whales in the North Pacific [9]. There are no reliable estimates for the abundance of humpback whales in the western Pacific stock because surveys of the known feeding areas are incomplete, and not all feeding areas are known [9].

The 2010 estimate of abundance of humpback whales in the entire North Pacific Basin based on a Chapman-Petersen estimate is 21,808 (CV=0.04) [10].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Prepared by the Humpback Whale Recovery Team for the Silver Spring, Maryland. 105pp.

[2] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A.

[3] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae): Gulf of Maine Stock, revised Dec. 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[4] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae): Eastern North Pacific Stock, revised May 15, 2005. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[5] Calambokidis J., T. Chandler, L. Schlender, G.H. Steiger, and A. Douglas. 1995-2000. Final reports to Monterey Bay, Channel Islands, and Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuaries, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, and University of California at Santa Cruz. Cascadia Research, 218 1/2; W Fourth Ave., Olympia, WA 9850. Accessed at http://www.cascadiaresearch.org/abstracts/abstract.htm.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae): Central North Pacific Stock, revised Feb 12, 2005. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[7] NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Cetaceans: Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises. Humpback Whale. Website <http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/humpback_whale.doc> accessed January, 2005.

[8] Mobley J. Jr., S. Spitz, and R. Grotefendt. 2001. Abundance of Humpback Whales in Hawaiian Waters: Results of 1993-2000 aerial surveys. Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Dept of Commerce. Available at <http://hawaiihumpbackwhale.noaa.gov/research/HIHWNMS_Research_Mobley.pdf>.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae): Western North Pacific Stock, revised Feb 5, 2005. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Draft Stock Assessment Report. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae): Central North Pacific Stock, revised Jan 28, 2010. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

Laysan duck (Anas laysanensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 7/7/2009 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

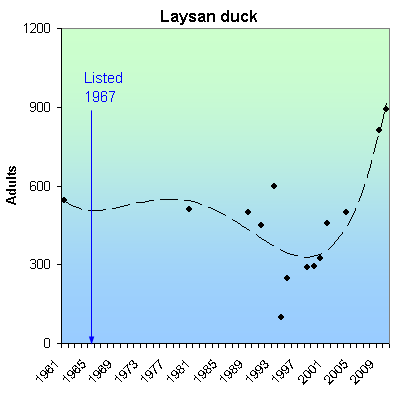

By the late 19th century, the Laysan duck had disappeared from most of the Hawaiian Islands due to exotic predators, habitat loss and windblown sand. It is currently threatened by disease, tsunamis and storms, drought and small population size. In 1911 only seven adult ducks remained. The population grew to 440-600 by the 1950s as vegetation recovered. Thanks to a reintroduction program in 2004, the population grew to 891 adult birds on two islands in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Laysan duck (Anas laysanensis) formerly occurred throughout the Hawaiian Islands. By the late 19th century it was known only from Laysan Island and Lisianski Island [1]. Today the species survives only on Laysan Island and in a reintroduced population on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. The cause of its extirpation from the majority of the Hawaiian islands is unknown, but is presumed to have been induced by Polynesian colonizers and the mammalian predators, such as rats, that they brought with them.

The Laysan duck was first reported on Lisianski Island in 1828. Its fortune changed for the worse in 1844 when shipwrecked sailors washed ashore, eating the duck and other native species to survive [1]. Of greater long-term impact, however, was the accidental introduction of mice (Mus musculus) to the island later that year by a rescue ship. A second shipwreck party washed ashore in 1846. By 1857 mice had denuded the island, destroying the duck's habitat. By 1916 the mouse and rabbit population starved to death due to lack of vegetation [1]. Unencumbered by vegetation, windblown sand filled in the island's freshwater springs. The Laysan duck was extirpated from Lisianski some time between 1845 and 1857.

Laysan Island did not experience sustained human disturbance and was not colonized by humans until guano miners occupied it from 1891 to 1904 [5]. Within six months of arriving, they killed 300,000 nesting seabirds for food and sport. Their greatest impact, however, was the introduction of European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) that thoroughly denuded the island by the 1910s, reducing hiding cover and prey habitat and allowing windblown sand to bury freshwater springs and reduce the size of the island's central hypersaline lake [4]. The extinction of 14 species including the Laysan rail, Laysan honeycreeper and Laysan millerbird have been linked to the rabbit invasion [3]. Laysan was made part of the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation in 1909, but was not policed, allowing Japanese feather hunters to scour it in 1909 and 1910, killing Laysan ducks for food and feathers. The species was nearly driven to extinction, being reduced to less than 100 birds in 1902 and just 7 adults in 1911 and 1912 [1]. Rabbit eradication efforts were unsuccessful in 1912 and 1913, but having denuded the island, the species starved to death by 1923 [5]. Laysan duck numbers slowly increased as the vegetation grew back, allowing the species to increase to about 500 birds by 1957 [1].

Intermittent surveys suggest that the species maintained a population of 400-600 birds from 1957 to 2005, with the exception of a dramatic population crash in late 1993 and early 1994 due to sustained drought [1]. The population grew steadily from the 1994 low point back to about 500 birds in 2004 [1]. In 2004, 20 ducks were translocated to Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge [2]. The adult population was estimated at 811 in 2009 (Laysan: 611, Midway Atoll: 200) [5] and 891 in 2010 (Laysan: 521, Midway Atoll: 370) [6]. The population may have declined 20 percent to 30 percent in 2011 due to the March 2011 tsunami that overwashed much of both islands, denuding vegetation, contaminating freshwater wetlands with salt water and marine debris, and causing an outbreak of avaian botulism [7].

Prior the 2011 tsunami, the IUCN was considering downlisting the Laysan duck form "critically endangered" to "vulnerable" due to its 2004-2010 population increase [8].

Avian botulism is an important current threat on Midway Atoll, where outbreaks in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011 killed hundreds of adults, requiring intervention by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to remove dead birds and rehabilitate infected birds. Tsunamis and storms threaten both low-lying islands, as does drought. The Laysan population may have reached a carrying capacity of about 500 birds [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the Laysan Duck (Anas laysanensis). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. vii + 94 pp.

[2] Klavitter. 2006. Personal communication with John Klavitter, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, January 16, 2006.

[3] Center for Biological Diversity. 2005. Database of Extinct, Endangered and Vulnerable Species. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ.

[4] Moulton, D. W., and A. P. Marshall. 1996. Laysan Duck (Anas laysanensis). In The Birds of North America, No. 242 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Revised Recovery Plan for the Laysan Duck (Anas laysanensis). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. ix + 114 pp. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/090922.pdf

[6] Reynolds, M. 2011. Letter from Michelle Reynolds to IUCN Species Survival Commission, February 21, 2011. http://www.birdlife.org/globally-threatened-bird-forums/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Anas-laysanensis-Reynolds-Feb11.pdf

[7] Reynolds, M. 2012. Post on Birdlife International website dated January 16, 2012. http://www.birdlife.org/globally-threatened-bird-forums/2011/06/laysan-duck-anas-laysanensis-downlist-to-vulnerable

[8]. BirdLife International. Global Threatened Birds Forum: Laysan Duck (Anas laysanensis): downlist to Vulnerable? http://www.birdlife.org/globally-threatened-bird-forums/2011/06/laysan-duck-anas-laysanensis-downlist-to-vulnerable.

Laysan finch (Telespiza cantans)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/4/1984 |

Range: HI(b) ---

SUMMARY

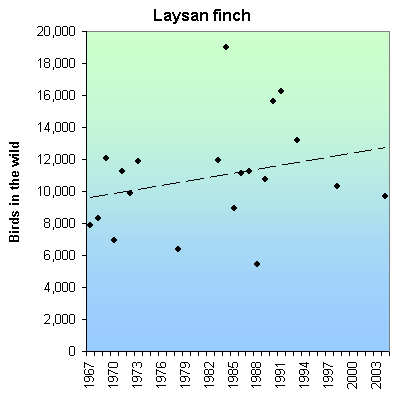

The finch is endemic to Laysan Island, Hawaii. It declined precipitously following the introduction of rabbits that denuded the island of vegetation, but increased following rabbit removal. It remains threatened by invasive species and sea-level rise. The Laysan finch was nearly driven to extinction by habitat damage caused by invasive rabbits. At listing in 1967 the total population was estimated at 7,779 birds. The population fluctuates widely, but was estimated at 17,780 birds in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

The Laysan finch (Telespiza cantans) is a member of the honeycreeper family. Adult males are 7.5 inches long and have a yellow head, breast, and back, a gray neck collar, and whitish belly. The finch is endemic to Laysan Island in the northwest Hawaiian islands. It declined precipitously following the introduction of rabbits to Laysan Island in 1903. A number of endemic birds became extinct when the rabbits destroyed the island’s vegetation. Rabbits were eliminated in 1923, and the Laysan finch slowly began to recover. A population of finches was introduced to Midway Island in 1891, but was wiped out by invasive rats during World War II [1]. The Laysan finch currently exists in two populations in the northwestern Hawaiian islands-- in the natural population on Laysan Island and in a small translocation-founded population at Pearl and Hermes Reef [3].

Finch population censusing began in 1966, and the finch was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1967. In 1967, the total population was estimated at 7,779 birds, and the population has fluctuated since that time. In 1976 there were 20,802 birds, but in 1978 there was a sharp decline to 6,188 birds. The population increased to 18,274 birds in 1984, but fell to 5,201 birds in 1988. The 2004 population was estimated at 9,393 birds [2]. The most recent population estimate from 2006 is 17,780 birds [3].

A population of 108 birds was introduced to the four islets of Pearl and Hermes Atoll in 1967 [1, 2]. This population has also fluctuated significantly, with three of the islet subpopulations dying out at least once. Although the population has a positive population trend, it is unstable and will always remain small due to the carrying capacity of the islets. The 2004 population at Pearl and Hermes was estimated at 329 birds, down from 1,105 birds in 2002 [3].

The population on Laysan Island is threatened by habitat loss due to sea-level rise caused by global climate change. The spread of the invasive plant Verbesina encelioides at Pearl and Hermes Reef has led to the near-complete loss of native vegetation on Southeast Island, which harbors the largest population of Laysan finches. The birds nest and forage in habitat dominated by V. encelioides during its summer growing season, but when this annual plant dies back for the winter, the finches are left with little or no food resources; population modeling experiments indicate that this habitat degradation substantially increases the extinction risk for the Pearl and Hermes population [3].

Efforts currently are under way to evaluate potential future translocation sites for this species [3].

CITATIONS

[1] Morin, M. P. and S. Conant. 2002. Laysan Finch (Telespiza cantans) and Nihoa Finch (Telespiza ultima). In The Birds of North America, No. 639 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[2] Freifeld, H. 2005. Laysan finch popuation status, 1966-2005. Data provided by Holly Freifeld, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Honolulu, HI, September 23, 2005.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Laysan finch (honeycreeper) (Telespiza cantans) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. 13 pp.

Pacific green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizi)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 1/12/1998 |

Range: AS(b), CA(s), GU(b), HI(b), MP(b), OR(o), WA(o) ---

SUMMARY

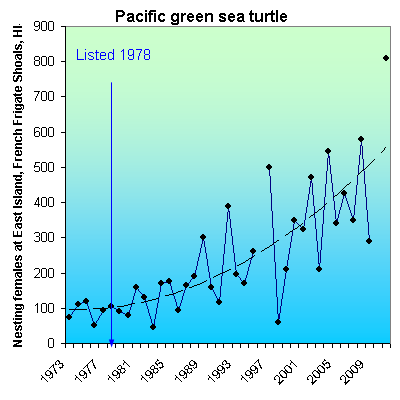

Green sea turtles in the Pacific are threatened by habitat loss, egg collection, hunting, beach development, bycatch mortality in commercial fisheries, and sea level rise due to global warming. Since being protected in 1978, the number of females nesting at East Island of French Frigate Shoals, approximately half of the total Hawaii population, increased from 105 in 1978 to 808 in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 5]. It migrates long distances between foraging and nesting areas [5]. Typical near-shore habitats are shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches. Females generally reproduce every two or more years, with an average of three to four nests during a breeding year.

U.S. populations occur in the Atlantic from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean, and in the Pacific from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 5]. Nesting populations within the United States have increased in size since the species was protected in 1978.

The taxonomic distinctions between Pacific and East Pacific populations of green sea turtle are under review. It remains unresolved whether C. mydas agassizii qualifies as a separate species or a subspecies of green sea turtle.

HAWAII AND THE FAR PACIFIC

In Hawaii, most nesting occurs at East Island of French Frigate Shoals [2, 6]. Nesting females increased there from 75 in 1973 to 808 in 2011 due to cessation of hunting and protection of habitat [6, 8]. The number of nesting females at East Island represents approximately half of the estimated number of nesting females in all of Hawaii [9].

Other U.S.-associated Pacific Islands that support green sea turtle populations include American Samoa (25-35 nesting females), the Federated States of Micronesia (three atolls, more than 100 nesting females) and Guam (little but regular nesting) [2]. In general, the major threat on urbanized Pacific islands is habitat loss and problems associated with rapidly expanding tourism. In particular, human development is having an increasingly serious impact on green sea turtle nesting beaches. On rural and developing islands, including American Samoa and some islands of the Northern Mariana Islands and Micronesia, human consumption of turtles remains a problem. The relatively recent increase in fibropapillomatosis (a tumorous disease) is a concern [2].

U.S. MAINLAND

The population status and migratory habits of East Pacific green turtles frequenting waters off the U.S. West Coast are unknown, and there are no known nesting sites in the United States [3]. Severe population declines in this population over the past 30 years were due largely to massive overharvesting of wintering turtles in the Sea of Cortez from 1950-1970 and intense collection of eggs between 1960 and early 1980 on mainland beaches of Mexico. The population was thought to be declining as of 1998. A small group (30-50) of resident East Pacific green sea turtles is found in San Diego Bay. Although they do not nest in the United States, this group appears to remain in the area for much of the year because of the warm water effluent from a power-generating station [2]. There is a ban on high-speed boat traffic in the south portion of the bay, but it is rarely enforced and boat strikes may pose a threat [2].

CITATIONS

[1] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, Maryland.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[3] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the East Pacific Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. National Marine Fisheries Service, Washington, DC.

[6] Tiwari, M., G.H. Balazs and S. Hargrove. 2010. Estimating carrying capacity at the green turtle nesting beach of East Island, French Frigate Shoals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 419:289–294.

[7] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 105 pp.

[8] Maison, K.A., I. Kinan Kelly and K.P. Frutchey. 2010. Green Turtle Nesting Sites and Sea Turtle Legislation throughout Oceania. U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-F/SPO-110, 52 pp. http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/tm/110.pdf

[9] Ishizaki, A. 2012. Personal communication. Protected Species Coordinator, Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. May 19, 2012.