American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 8/13/1989 | Recovery plan: 9/27/1991 |

Range: AR(b), KS(b), MA(b), NE(b), OH(b), OK(b), RI(b), SD(b), TX(b) --- AL(x), CT(x), DE(x), DC(x), FL(x), GA(x), IL(x), IN(x), IA(x), KY(x), LA(x), ME(x), MD(x), MI(x), MN(x), MS(x), MO(x), MT(x), NH(x), NY(x), NJ(x), NC(x), ND(x), PA(x), SC(x), TN(x), VT(x), VA(x), WV(x), WI(x)

SUMMARY

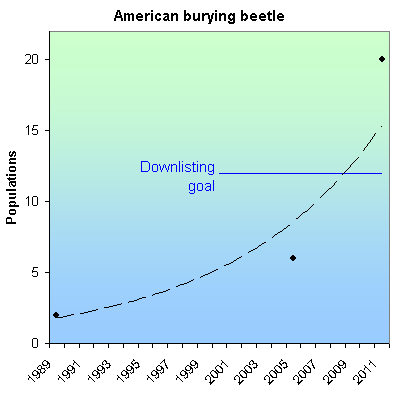

The cause of the American burying beetle's 90% range loss is not well understood, but is thought to be due to disruptions in the food and reproductive web. It is threatened by competition, drought, invasive ants and habatat loss. When listed as endangered in 1989, there were only two known populations. Captive breeding, reintroduction efforts and intensive surveys have increased the total number of populations to 20 or more in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) is a large, spectacularly colored orange and black insect. It formerly occurred across a vast range from Nova Scotia south to Florida, west to Texas, and north to South Dakota. It was documented in 150 counties in 34 states, the District of Columbia, and three Canadian provinces. Total historical numbers are not known, but the species may well have occurred in the tens of millions. The burying beetle's dramatic decline has been called "difficult to imagine" and “one of the most disastrous declines of an insect’s range ever to be recorded” [2]. It was extirpated from mainland New England through New Jersey by the 1920s, from the entire mainland east of the Appalachian Mountains by the 1940s, and from the mainland east of the Mississippi River by 1974. It is absent from about 90 percent of its historic range.

The largest of North America's 32 burying beetles, N. americanus is uniquely dependent upon quail-size carrion weighing 100 to 200 grams [1, 15]. Males smell freshly dead mammals and birds (and occasionally even fish) within an hour of death and up to two miles away. Females arrive shortly thereafter, attracted by male pheromones. A competition ensues and is typically won by the largest male and female. Lying on their backs, the winning couple inches the carrion into an excavated burial chamber. During this time, orange phoretic mites borne by the beetles leap to the carcass, cleaning it of fly eggs and microbes. The buried carcass is relieved of its feathers, feet, tail, ears and/or fur. Now known as a "brood ball," it is coated with oral and anal embalming secretions to retard fungal and bacterial growth. The beetles then mate and within 24 hours lay eggs in the soil near the carcass. White grubs emerge three or four days later and are carried to the carcass. The parents also defend the grubs from predators and feed them regurgitated food. The American burying beetle is one of the few non-colonial insects in the world to practice dual parenting. In approximately a week, the grubs leave the chamber and pupate into adults.

The cause of the American burying beetle's decline is not well understood, but the most cogent hypotheses see it as victim of interacting food chain disturbances which reduced the number of large carcasses [2]. The passenger pigeon, which formerly occurred in the billions, was an ideal size. It was last seen in 1914 and was greatly reduced in number in the decades preceding. Its decline and disappearance occurred just prior to the burying beetle's. Other endangered or greatly reduced carrion of ideal size include the black-footed ferret, northern bobwhite, and greater prairie chicken. Competition for dwindling carrion numbers was exacerbated by increasing numbers of mid-sized predators following the extinction or decline of large predators such as the eastern cougar, mountain lion and gray wolf. In their absence, coyotes, raccoons, fox and other mid-size scavengers increased in number and consumed more quail-size carrion. Finally, as habitats became more fragmented mid-size predators were increasingly able to exploit forest and grassland edges, taking more carrion.

At the time of listing in 1989, two populations were known: one on Block Island, Rhode Island and one in eastern Oklahoma [1]. Since then, populations have been discovered in South Dakota (1995), Nebraska (1992), Kansas (1997), Arkansas (1992) and Texas (2003), as well as additional populations in Oklahoma [3, 23]. The total number of populations has increased to at least 20 as of 2011 [7, 11, 13, 10, 22, 23].

RHODE ISLAND. Located 12 miles off the south coast of Rhode Island, Block Island supports the last natural population of the American burying beetle east of the Mississippi River. The island is free of foxes, raccoons, skunks and coyotes. A study of one-third of the population determined that it was relatively stable between 1991 and 1997 (mean=184), steadily grew to 777 in 2006, and then declined to 80 in 2011 in part because of a reduction in supplementation of carcasses [8]. This population served as the source for the successful Roger Williams Park Zoo captive breeding program initiated in 1994 and for direct translocations to Nantucket and Penikese Island.

MASSACHUSETTS. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Massachusetts shortly after 1940 [1] and was reintroduced to the 70-acre Penikese Island in Buzzards Bay over a four-year period between 1990 and 1993. Reintroduced beetles initially came from a Boston University captive breeding population originating from Block Island stock [6]. The population persisted at low numbers through 2002, but was not located in 2003, 2004 or 2005. On Nantucket, 2,892 beetles were introduced from the Roger Williams Park Zoo between 1994 and 2005 to the Audubon Society’s Sesachacha Heathland Wildlife Sanctuary (east side of the island) and the Nantucket Conservation Foundation’s Sanford Farm (west side of the island) [5, 6, 21]. Existing and new beetles were trapped and provisioned with quail carcasses each summer to boost larva production [5]. The introduction program ended in 2005 in order to determine if population is self-sustaining [6]. The Penikese Island reintroduction effort has been deemed a failure, and the success of the Nantucket effort is unknown, although the population is believed to persist [23].

OHIO. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Ohio shortly after 1974 when it was last seen near Old Man's Cave in Hocking Hills State Park [9, 10]. A short-lived captive population derived from Block Island stock was established in 1991 at the Insectarium of the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden [1]. In July 1998, Ohio became the site of the first mainland introduction when 35 pairs of beetles taken from a wild population near Fort Chaffee, Ark. were introduced to the Waterloo Wildlife Experiment Station in southeast Ohio [10]. The Waterloo population was augmented in 1999 (20 pairs and 15 females) and 2000 (33 pairs and four males), but not 2001 or 2002. Additional augmentation occurred in 2003. A captive population established at Ohio State University in 2002 produced 828 beetles as of 2004; 199 of these were used for reintroductions in 2003 and 156 were reintroduced in 2004. The Wilds (managed by the Columbus Zoo) plans to create a second captive colony [10] and a second reintroduction is planned for the Athens District of the Wayne National Forest [11]. The success of the Ohio reintroduction efforts is unknown but is thought to be limited [23].

MISSOURI. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Missouri in the early 1980s [1]. It has not been relocated despite repeated and recent surveys [12]. A captive breeding population was established at the Monsanto Insectarium, St. Louis Zoo in 2004 (with 10 pairs from Ohio State University) and 2005 (with wild beetles from Arkansas) [7, 15]. Six-hundred-fifty-four adults were produced as of June 2005, 50 of which were transferred to Ohio State University. Plans are being developed to introduce the species to The Nature Conservancy and Missouri Department of Conservation lands. [7].

OKLAHOMA. The presence of American burying beetles has recently been confirmed in 22 eastern Oklahoma counties, reported but unconfirmed in two more, and likely to occur in nine more [16]. The largest known concentrations are a population at Camp Gruber and a smaller one on private timber lands held by Weyerhaeuser International. Captures (not to be confused with population estimates) at Camp Gruber fluctuated around a mean of 213 adults between 1992 and 2003 without discernable trend. Captures at Weyerhaeuser had a mean of 52 adults between 1997 and 2003, but this population collapsed in 2006 and 2007, perhaps due to drought or fire ants [23].

NEBRASKA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Nebraska in 1992 [18]. Between 1995 and 1997, nearly 1,000 individuals were trapped or collected in the upland grasslands and cedar tree savannas of the dissected loess hills south of the Platte River in Dawson, Gosper and Lincoln counties of Nebraska. The population is estimated at about 3,000 adults.

SOUTH DAKOTA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in South Dakota in 1995 and is believed to have a statewide population in excess of 500 adults [17].

ARKANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Arkansas in 1992 [3]

KANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Kansas in 1997 [19].

TEXAS: The American burying beetle, thought to be extirpated from Texas since the 1930s, was rediscovered in 2003 [3]. Two populations are now known to exist, one on a military base, the other on a Nature Conservancy preserve.

The American burying beetle recovery plan states: "The interim objective [extinction avoidance] will be met when the extant eastern and western populations are sufficiently protected and maintained, and when at least two additional self-sustaining populations of 500 or more beetles are established, one in the eastern and one in the western part of the historical range. Reclassification will be considered when (a) 3 populations have been established (or discovered) within each of four geographical areas (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and the Great Lake states), (b) each population contains 500+ adults, (c) each population is self-sustaining for five consecutive years, and, ideally, each primary population contains several satellite populations.”

The beetle remains threatened by the limited availability of carcasses to use for reproduction, by invasive species such as fire ants which compete for carcasses, and by drought and climate change. The Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport tar sands oil from Canada to Texas, is a new threat to the beetle in 2011 and would cut through the core of the beetle's range in South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

CITATION

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) recovery plan. Newton Corner, MA.

[2] Sikes, D.S. 2002. A review of hypotheses of decline of the endangered American burying beetle (Silphidae: Nicrophorus americanus Olivier). Journal of Insect Conservation 6: 103–113

[3] Quinn, M. 2006. American Burying Beetle (ABB). Website (http://www.texasento.net/ABB.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[4] Peyton, M.M. 1997. Notes on the range and population size of the American Burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) in the dissected hills south of the Platte River in central Nebraska. Paper presented at the 1997 Platte River Basin Ecosystem Symposium, Feb. 18-19, 1997 Kearney Holiday Inn Kearney, Nebraska.

[5] Mckenna-Foster, A.A., M.L. Prospero, L. Perrotti, M. Amaral, W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction to Nantucket, MA, 2004-2005. Abstract presented at the First Nantucket Biodiversity Initiative Conference, September 24, 2005, Coffin School, Egan Institute of Marine Studies, Nantucket, MA.

[6] Amaral, M. 2005. Personal communication with Michael Amaral, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Concord, NH, November 28, 2005.

[7] Homer, P. 2005. Missouri's Threatened and Endangered Species Accomplishment Report: July 1, 2004 - June 30, 2005. Missouri Department of Conservation.

[8] Raithel, C. 2012. American burying beetle, Southwest Block Island trend, 1991-2011. Spreadsheet provided by Christopher Raithel, Rhode Island Dept of Environmental Management, Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, April 5, 2012.

[9] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2005. American Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus americanus. Website (www.dnr.state.oh.us/wildlife/Resources/projects/beetle/beetle.htm) accessed January 28, 2006.

[10] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2004-2005 Wildlife Population Status and Hunting Forecast.

[11] Wayne National Forest. 2004. Schedule of Proposed Action, 10-01/04-12/31/04.

[12] Stevens, J. and B. Merz. American Burying Beetle Survey in Missouri. St. Louis Zoo, Department of Invertebrate. Website (http://biology4.wustl.edu/tyson/projectszoo.html) accessed January 29, 2006.

[13] Dabeck, L. 2006. The American Burying Beetle Recovery Program: Saving nature's most efficient and fascinating recyclers. Roger Williams Park Zoo. Website (www.rogerwilliamsparkzoo.org/conservation/burying%20beetle%20program.cfm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[14] Kozol, A. J. 1990. NICROPHORUS AMERICANUS 1989 laboratory population at Boston University: a report prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Unpublished report.

[15] Stevens, J. 2005. Conservation of the American burying beetle. CommuniQue, September, 2005:9-10.

[16] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Website (www.fws.gov/ifw2es/Oklahoma/beetle1.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[17] South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. 2006. The American Burying Beetle in South Dakota. Website (www.sdgfp.info/Wildlife/Diversity/ABB/abb.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[18] Peyton, M.M. 2003. Range and population size of the American burying beetle (Coleoptera:Silphidae) in the Dissected Hills of South-central Nebraska. Great Plains Research 13(1): 127-138

[19] Miller, E.J. and L. McDonald. 1997. Rediscovery of Nicrophorus americanus Olivier (Coleoptera Silphidae) in Kansas. The Coleopterists' Bulletin 5(1):22.

[20] Mckenna-Foster, A., W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction on Nantucket 2005. Unpublished report.

[21] Perrotti, L. 2006. Roger Williams Park Zoo American Burying Beetle Project Statistics. Spreadsheet provided by Lou Perrotti, American Burying Beetle project coordinator, Roger Williams Park Zoo, Providence, RI, February, 2006.

[22] NatureServe. 2011. American Burying Beetle Species Profile. Available at: http://www.natureserve.org

[23] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. American Burying Beetle (Nicropherus americanus) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation. 53 pp.

El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides allyni)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/1/1976 | Recovery plan: 9/28/1998 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

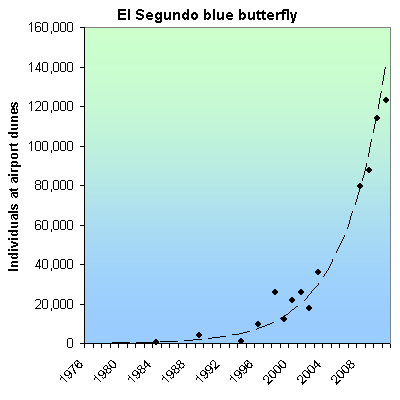

The El Segundo blue butterfly lost approximately 90 percent of its oceanside habitat to construction of the Los Angeles Airport and a housing development. The remaining habitat was highly degraded and overtaken by exotic plants that crowded out its host. The butterfly declined from about 1,000 individuals in the late 1970s, when listed as an endangered species, to about 500 in 1984 before being saved by restoration efforts that steadily increased the population at the Airport Dunes to 123,000 in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The El Segundo blue butterfly (Euphilotes battoides ailyni) formerly extended over much of the 3,200-acre El Segundo Dunes of Los Angeles County, Calif. The dunes ranged from Ocean Beach (near Santa Monica) south to Magala Cove in Palos Verdes and were bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and the east by Los Angeles coastal prairie.

The El Segundo blue occupied areas within the dunes with high sand content and its obligate host plant, coast buckwheat (Eriogonum parvifolium). The historic population size likely averaged 750,000 butterflies per year [2]. The prairie has since been entirely converted to an urban landscape and the dunes reduced to about 307 mostly degraded acres. The extent of habitat loss peaked, and El Segundo blue numbers likely reached their nadir, in the late 1970s, when virtually all of the dunes were developed or degraded.

Restoration efforts were initiated in the 1980s. Virtually all remaining potential habitat was protected from private development due to geological, conservation and other restrictions by 1990 and was believed to be capable of supporting 100,000 butterflies if fully restored [2]. However, governmental development, especially by the city of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Airport (LAX) is still a significant threat [4].

AIRPORT DUNES

To end a long conflict with its neighbors, LAX condemned and removed 822 homes from 200 acres on its western border between 1966 and 1975 [2]. The airport has alternately sought to restore and destroy El Segundo blue habitat on the site. In 1975, about 70 percent of the back dune was excavated and recaptured to realign Pershing Drive [2]. The area was reseeded with California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum), which attracted competing nonnative moths and butterflies, suppressing El Segundo blue numbers. The foredune to the south and west, and last fragment of coastal prairie, were graded during this same period. Only about 40 of the 200 acres escaped degradation during the 1970s. The impacts extirpated 17 of 20 native mammals, seven of 31 butterfly species, seven of 18 amphibians and reptiles, and all five coastal scrub obligate birds [2]. Twenty-two of 73 native species present in 1940 were absent in 1989 and 19 of 51 of extant native plants were represented by fewer than 100 individuals [1].

The El Segundo blue was placed on the federal endangered species list in 1976. LAX proposed developing the dunes as a recreational site with a 27-hole golf course and a 92-acre butterfly preserve in 1982 [2]. In 1985 the California Coastal Commission refused to issue a permit for the project. In the late 1990s, LAX proposed to extend runway into the dunes [1]. In 1987 the city of Los Angeles initiated efforts to reduce California buckwheat and increase coast buckwheat populations. In 1992, the city of Los Angeles established a 203-acre Habitat Restoration Area within the dunes. In response, the population rose from approximately 400-700 in 1984 to about 123,000 in 2011 in response to the habitat restoration actions [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7].

CHEVRON BUTTERFLY PRESERE

The 1.6-acre Chevron butterfly preserve has been isolated by development since the 1950s [1]. It is estimated to have supported about 2,000 butterflies from 1965 to 1976 [2]. The population dropped to 1,600 in 1977, 681 in 1979, 400 in 1986 [2]. The decline may have been caused by dune stabilization or lepidopterists crisscrossing the small site, using a capture-release method that can harm butterflies, and removing 839 butterfly larvae for study [2]. In 1986, the preserve had 240 host plants and 1,000 introduced seedlings [2]. The 1996 population was estimated at 5,000 to 7,000 butterflies on 1,200 host plants [1]. The population increase has been attributed to intensive management for the El Segundo blue [1].

MALAGA COVE

The El Segundo blue population was discovered on an eroded and iceplant dominated site in Malaga Cove in 1983 [2]. It had 60 butterflies and fewer than 50 host plants on 1 acre in 1984 [2]. It was fenced in 1986 [2]. Host plants and butterfly populations in 1990 were similar to the 1984 count [2]. The site was degraded by illegal dumping in 1997 [1]. In 2004 it supported 10-30 butterflies [3]. An adjacent population was discovered in 2000 in coastal bluff scrub habitat at York Long Point [3].

BALLON WETLANDS

A single male was reported but not captured at a potentially suitable six-acre private land site within Ballona Wetlands in 1985 [2]. Fifteen host plants but no butterflies were found there on a small dune fragment in 1986 [2]. By 1989 half the plants were dead [2]. A seven-acre site was seeded with native plants in 1990 but was significantly disturbed by a lagoon restoration project in 1997 [1]. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a permit to reintroduce the species prior to 1990, but the program has not been carried out [2].

HYPERION

A single butterfly was observed in the late 1980s near a remnant dune on a 30-acre site east of the Hyperion sewage treatment plan [1]. The site was extensively planted with exotic vegetation in 1995 by the cities of El Segundo and Los Angeles [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. El Segundo Blue (Euphilotes battoides allyni) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

[2] Mattoni, R. 1990. The endangered El Segundo blue butterfly. Journal of Research on the Leptidoptera 29(4):277-304.

[3] Mattoni, R., T. Longcore, C. Zonneveld and V. Novotny. 2001. Analysis of transect counts to monitor population size in endangered insects: the case of the El Segundo blue butterfly, Euphilotes battoides allyni. Journal of Insect Conservation 5:197-206.

[4] Rich, C. 2003. Letter from Catherine Rich, Executive Director, The Urban Wildlands Group, to Cindy Miscikowski, Los Angeles Councilwoman, August 4, 2003.

[5] Los Angeles World Airports. 2012. LAX’s 2011 El Segundo blue butterfly population count increases eight percent over previous year. Press release available at http://www.lawa.org/newsContent.aspx?ID=1547

[6] Sapphos Environmental, Inc. 2005. LAX Master Plan Final EIS, Appendix A-3c: Los Angeles/El Segundo Dunes Habitat Restoration Plan. Los Angeles World Airports, U.S. Department of Transportation, and Federal Aviation Administration.

[7] Los Angeles World Airports. 2011. LAX’s El Segundo blue butterfly count increases thirty percent over 2009. Press release available at http://vny.aero/newsContent.aspx?ID=1394 [8] Marroquin, A. 2009. Once-endangered El Segundo blue butterfly now thrives. DailyBreeze.com July 29. 2009. Available at http://news.duneguide.com/2009_07_01_archive.html

Palos Verdes blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus palosverdesensis)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/2/1980 | Listed: 7/2/1980 | Recovery plan: 1/19/1984 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

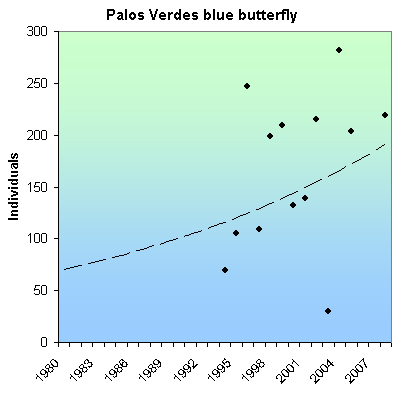

Habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation drove the Palos Verdes blue butterfly to near extinction. It remains threatened by severe weather, climate change, invasive species and fire suppression. This butterfly was protected as endangered in 1980. In 1984 it was believed extinct. It was then rediscovered, and a captive-breeding program was established. As of 2008 there were 219 butterflies.

RECOVERY TREND

The Palos Verdes blue butterfly (Glaucopsyche lygdamus paloverdesensis), a subspecies of the silvery blue, was discovered in the early 1970s [1]. It was originally found on the cool, fog-shrouded seaward side of the Palos Verdes Hills on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles County [2] and was subsequently found on the inland side of the peninsula [3]. The Palos Verdes blue (PVB) is dependent on two known host plants, locoweed (Astragalus trichopodus var. lonchus), also known as Santa Barbara milkvetch, and common deerweed (Lotus scoparius) [2]. An adult flight period occurs from late January through mid-April [2]. Eggs are typically laid in the flower heads of either deerweed or locoweed where the caterpillars then feed [2]. When the larvae mature, they crawl into the leaf litter to pupate. The pupae emerge as the next generation of adult butterflies in spring [2].

The historic PVB population was likely continuous across the 5,000 hectares of coastal scrub habitat that covered the south half of the Palos Verdes peninsula [1]. Intensive development of this area began in the 1950s and by the time of its discovery in the early 1970s, the PVB was already reduced to a few habitat fragments. By 1994 the 500 hectares of habitat remaining was not continuous and consisted of a mosaic of coastal sage scrub assemblages interspersed with disturbed patches [1]. When the Palos Verdes blue was listed in 1980, three localities known to support the species were listed as critical habitat [4]. Host plants on two of these sites were extirpated by 1985 due to the spread of weeds and annual grasses [4]. At the third site, construction by the city of Rancho Palos Verdes at Hesse Park in 1982 (in violation of the federal Endangered Species Act) destroyed what was then probably the second-largest remaining PVB colony [1].

Although population numbers were not estimated in the 1980s, there were probably fewer than 300 adults among all remaining habitat fragments [1]. In 1983, there were sightings of only four to seven adult PVBs [1]. Loss of habitat in combination with extremely harsh winters in 1983 and 1984 was thought to have led to the extinction of the PVB [1]. For 11 years, the PVB was thought to be extinct. Then, in 1994 the butterfly was re-discovered at the Defense Fuel Support Point managed by the Department of Defense at San Pedro, Calif. [1].

The rediscovered population was composed of only a few hundred individuals [5]. Because this single population was in danger of extinction from stochastic factors, a captive propagation effort was started and efforts to restore habitat were initiated [5]. The captive rearing program has maintained a captive population of PVB since 1995 [5]. Breeding results were poor from 1995 to 1998 but saw increased success in 1999 when 627 pupae were produced. In 2000, 968 pupae were produced [5]. In 2004, 231 were produced followed by 93 in 2005 [3]. Since 1994, captive reared butterflies have been used to augment the existing colony and in 2000 pupae were reintroduced to a nearby natural area known as the Chandler preserve, which resulted in the emergence of 306 PVB adults [6]. The reintroduced butterflies mated and eggs were deposited on more than 1,000 food plants on the six-acre natural area [6]. By 2000, 17 acres around the Defense Fuel Support Site had been planted with native vegetation [6].

Estimated PVB populations have fluctuated since 1994 [7]. In 2003 the population dropped from an estimated 215 individuals to 30 but recovered to 282 in 2004 [7] and 204 in 2005 [3]. Large increases and decreases in population are expected since butterfly abundance is known to vary with environmental conditions, especially with weather, and because they may be capable of multi-year diapause [7]. An analysis of occupancy trends at monitoring transects suggests a decline in area occupied by the PVB [7]. Although this could be due to actual declines, it could also indicate a shift in occupancy [6]. Monitoring transects have remained at fixed locations, and it is possible that the butterflies have moved as successional habitat matured [7]. Regardless, recovery efforts should concentrate on providing more habitat for the PVB. Currently weed control efforts, off-road vehicle use, nonnative plant invasion, and fire suppression negatively impact PVB habitat [2]. As of 2008 there were 219 butterflies [8].

CITATIONS

[1] Mattoni, R. 1995. Rediscovery of the endangered Palos Verdes blue butterfly, Glaucopsyche lygdamus palosverdesensis Perkins and Emmel (Lycaenidae). Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 31(3-4)180-194.

[2] The Butterfly Conservation Initiative. American Zoo and Aquarium Association. The Palos Verdes Blue Butterfly. Website http://www.butterflyrecovery.org/species_profiles/palos_verdes_blue/

[3] Longcore, T. 2005. Personal communication with Travis Longcore, Urban Wildlands Center, University of California.

[4] Arnold, R. A., 1987. Decline of the endangered Palos Verdes Blue Butterfly in California. Biological Conservation 40(3):203-217.

[5] Mattoni, R., T Loncore, Z. Krenova, A. Lipman. 2003. Mass rearing of the endangered Palos Verdes blue butterfly Glaucopsyche lygdamus palosverdesensis (Lycaenidae). Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera. 37:55-67.

[6] Mattoni, R. and N. Powers. 2000. The Palos Verdes Blue; an Update. The Endangered Species Bulletin. 25(6).

[7] Longcore, T., and R. Mattoni. 2005. Final Report for 2005 Palos Verdes Blue Butterfly Adult Surveys on Defense Fuel Support Point, San Pedro, California. Los Angeles: The Urban Wildlands Group (Defense Logistics Agency Agreement # N68711-05-LT-A0012). 11 pp.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Palos Verdes Blue Butterfly 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad, CA. 16 pp.

Socorro isopod (Thermosphaeroma thermophilum)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/27/1978 | Recovery plan: 2/16/1982 |

Range: NM(b) ---

SUMMARY

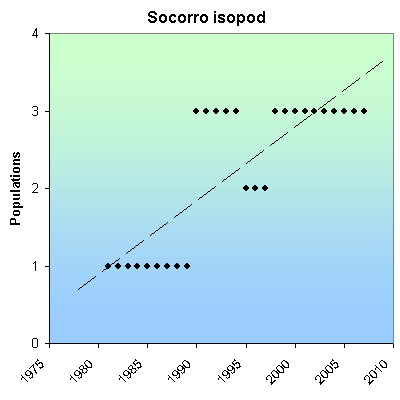

The Socorro isopod was reduced to a single spring due to water diversions. It was protected in 1978. After the species was nearly driven to extinction by an accident in 1988, three new populations were established on site and in a research park. All populations were stable as of 2009.

RECOVERY TREND

The Socorro isopod (Thermosphaeroma thermophilum) is a crustacean that is only found in New Mexico. The historical distribution of the Socorro isopod likely included Cook, Socorro and Sedillo warm springs which together fed a marsh extending for a half mile to the east of Cook Spring. Cook and Socorro Spring were capped and their water diverted to the city of Socorro, N. M.. The marsh no longer exists.

The Sedillo Spring population remained stable between 1978, when it was listed as an endangered species, and August 1988 when all isopods in the pool were nearly extirpated by invasive root growth that blocked the spring outflow [2]. Flows were restored a month later, perhaps flushing a small number of native isopods from the underground plumbing into the pool. These were successfully augmented with isopods that had been housed at the biology department of the University of New Mexico. In response to the near extinction, the Socorro Isopod Propagation Facility was established in 1990. The facility consists of two separate systems of four artificial pools connected by pipes. A total of 600 isopods (75/pool) were introduced in 1990. By 1995, the south branch of the propagation facility was extirpated while the north branch had stabilized. In 1999, the north branch was extirpated due to two accidents. Four-hundred isopods were introduced to the south branch (100/pool) in 1999. A third captive population was established at the Albuquerque Biological Park in 1998 [3]. The two facilities have increased the total size of the population, the total extent of available habitat, and the number of independent populations [2].

Ongoing threats to the species include disruption of thermal groundwater discharge from surface and sub-surface explosive tests on Department of Defense lands immediately west of the natural spring, vandalism, and other human-caused modification of spring flows [3]. Between 1995 and 2002 vandals removed a valve and a protective culvert controlling flow to the spring, diverted and occluded the surface flow, removed the concrete wall lining the spring pool, dumped a junk car immediately adjacent to the spring, and removed vegetation from the propagation facility pools [3, 4]. Captive populations at the Socorro Isopod Propagation Facility have diverged morphologically and genetically from the native population [5]. Since September 1999, the three populations have remained stable while demonstrating typical annual variations [6]. Delisting is not possible until the species' natural habitat on private land is secured with a conservation agreement [6].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982. Socorro isopod (Thermosphaeroma thermophilum) Recovery plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, NM.

[2] Lang, B.K., D.A. Kelt and S.M. Shuster. In press. The role of controlled propagation on an endangered species: demographic effects of habitat heterogeneity among captive and native populations of the Socorro isopod (Crustacea: Flabellifera). Biodiversity and Conservation, in press.

[3] New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. 2004. Threatened and Endangered Species, 2004 Biennial Review, Final Draft Recommedations. New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM.

[4] New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. 2002. Threatened and Endangered Species, 2002 Biennial Review. New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM.

[5] Shuster, S.. M., M. P. Miller, B. K. Lang, N. Zorich, L. Huynh and P. Keim. 2005. The effects of controlled propagation on an endangered species: Genetic differentiation and divergence in body size among native and captive populations of the Socorro Isopod (Crustacea: Flabellifera). Conserv. Genetics. 6: 355-368.

[6] New Mexico Department of Fish and Game. 2009. Interim Report: New Mexico Endangered Invertebrates Monitoring and Management. Project Number: E-37-11.

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 1/9/1991 | Recovery plan: 11/17/2000 |

Range: AL

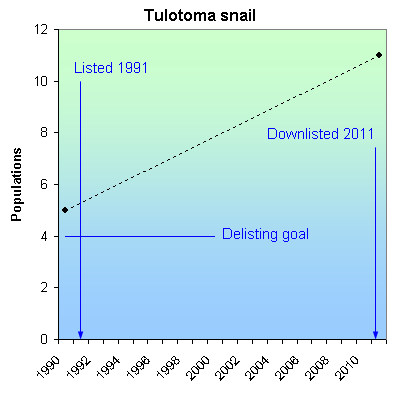

SUMMARY

The tulotoma declined due to dams and water quality degradation. Ongoing threats include droughts, spills and pollution. Since listing in 1991, the tulotoma increased from 10,000 to more than 100 million individuals as of 2011. The number of populations also increased from six to 10.

RECOVERY TREND

The tulotoma snail (Tulotoma magnifica) is found only in Alabama. It was listed as an endangered species in 1991 and was downlisted to “threatened” in 2011 due to the completion of critical recovery plan goals [1]. At the time of listing in 1991, the tulotoma snail was known from five areas in the lower Coosa River drainage [1]. Tulotoma populations below Coosa River dams have increased due to actions by Alabama Power Company to improve flows and water quality [1]. Threats to the tulotoma snail have been reduced due to habitat improvements in the Coosa River, the discovery of six drainage populations of the species that were unknown at the time of listing, development of watershed management plans and protection of tulotoma snails under state laws [1].

Monitoring efforts have shown increased range and size in four of the five populations known in 1991 [1]. Spatial distribution and trends of four of these five tulotoma populations (all populations except Ohatchee Creek) were monitored annually between 1992 and 1995, in 1999, and in 2004 [1]. The lower Coosa River population has expanded throughout a six-mile reach and the species’ numbers in this reach are estimated at more than 100 million tulotoma [1]. Habitat in the Coosa River below Jordan Dam has improved and expanded due to implementation of a minimum flow regime below the dam and installation of an aeration system [1]. The tulotoma population has grown from an estimated 10,000 in 1991 to more than 100 million in the stretch between Jordan Dam and Wetumpka [2]. The Kelly Creek tulotoma population has expanded into suitable habitat in an approximately five-mile reach of the middle Coosa River above and below the confluence of Kelly Creek, likely as a result of implementation of pulsing flows below Logan Martin Dam to improve dissolved oxygen levels [2]. No tulotomas have been rediscovered from the Ohatchee Creek shoal population for 15 years, and it is believed to be extirpated [2].

At the time of listing, hydropower discharges were limiting the range and abundance of tulotoma to only a 3-kilometer (1.8-mile) reach of the Coosa River below Jordan Dam. Water discharges for hydropower purposes were released from Jordan Dam for 2.25 hours per day; at all other times, flow consisted of only dam seepage. As a result of the low water quantity, water quality problems -- particularly low dissolved oxygen and elevated temperatures -- were a significant limiting factor to tulotoma below Jordan Dam [2]. In 1992, the Alabama Power Company (APC) established minimum flows in the Coosa River below Jordan Dam, and later installed a draft tube aeration system to ensure maintenance of dissolved oxygen levels at or above state standard [2]. With increased flows, additional colonies have become established in the upper portion of the reach and into the downstream areas. The tulotoma has extended its range laterally within the channel in habitats made available by the constant minimum flows [2]. Thousands of colonies consisting of more than 100 million tulotoma now inhabit a six-mile reach of the Coosa River below the Jordan Dam [2].

The range of tulotoma has increased from six populations in 1991, occupying 2 percent of its 350-mile historical range, to a total of 10 populations, occupying 10 percent of the historical range. Habitat conditions have improved, occupied habitat has expanded in the Coosa River below Jordan Dam, and tulotoma numbers are now estimated at greater than 100 million individuals [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Reclassification of the Tulotoma Snail From Endangered to Threatened and Special Rule. 76 FR 31866

[2] Blackburn, P. 2011. Wetumpka Herald. Snail native to Coosa River no longer endangered. Website http://www.thewetumpkaherald.com/news/article_5b28e3f0-b4bb-11e0-9df8-001cc4c03286.html viewed on Oct 24, 2011.