Bighorn sheep (Peninsular Ranges DPS) (Ovis canadensis pop. 2)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 2/1/2001 | Listed: 3/18/1998 | Recovery plan: 10/25/2000 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

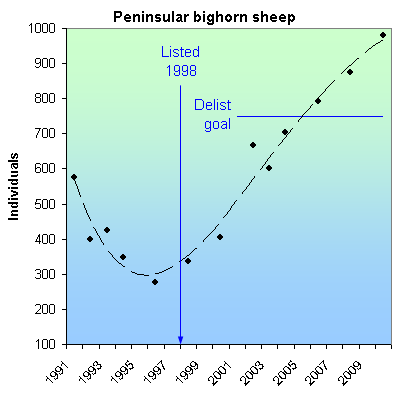

The Peninsular bighorn sheep declined to near extinction because of housing developments, agriculture, collisions with cars, predation by mountain lions and diseases contracted from domestic sheep. Sheep populations plummeted from 971 in 1971, to 276 in 1996, but since being listed as endangered in 1998, the number of bighorns has increased to 981 as of 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Peninsular bighorn sheep is a distinct population of bighorn (Ovis canadensis) that is restricted to east-facing, lower elevation slopes (typically below 4,600 feet) of the Peninsular Ranges along the northwest edge of the Sonoran Desert in southern California. Though populations occur in Mexico, the species is only listed as endangered from the San Jacinto Mountains south to the U.S.-Mexico border. It has declined due to loss of habitat to agriculture and housing development, car collisions, predation by mountain lions, diseases contracted from domestic sheep, disturbance by humans and dogs, fire suppression, and spread of exotic plants such as tamarisk [1]. It was listed as an endangered species in 1998. Critical habitat was designated on 844,897 acres in 2001, but was reduced to 376,938 acres in 2009 [3].

The historic population size is unknown, but the species was considered "rare" in 1971 when it was estimated at 971 animals [1]. The highest recent population was 1,171 animals in 1974 and 1979. The population plummeted to 276 in 1996 but following listing, increased to 981 as of 2010 [4]. Approximately 100 peninsular bighorn are captive-bred and used to augment the wild population [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. Recovery Plan for bighorn sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR. 251 pp.

[2] Bighorn Institute. 2005. Endangered Peninsular Bighorn Sheep, website (www.bighorninstitute.org/endangered.htm) accessed September 30, 2005.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Designation of Critical Habitat for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep and Determination of a Distinct Population Segment of Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni), Final Rule. 74 FR 17288.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Peninsular bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) 5 Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Carlsbad, CA.

Black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 8/8/1988 |

Range: AZ(b), CO(b), MT(b), SD(b), UT(b), WY(b) --- KS(x), NE(x), NM(x), ND(x), OK(x), TX(x)

SUMMARY

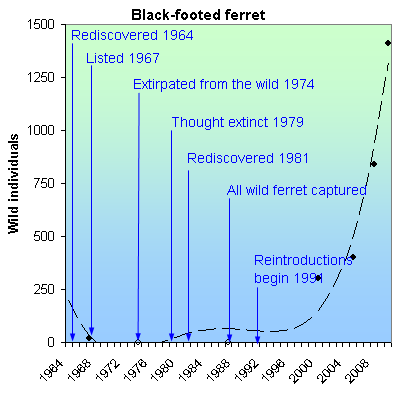

The black-footed ferret was nearly driven extinct due to the elimination of prairie dog colonies by habitat destruction, shooting and plague. It was thought extinct until 1964, extirpated from the wild in 1974, thought extinct again in 1979, then rediscovered in 1981. All ferrets were captured in 1987. A reintroduction program increased wild ferrets from 0 in 1991 to about 1,410 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), which once occurred throughout the grasslands and basins of interior North America, from southern Canada to Texas, is entirely dependent upon prairie dog colonies [1]. It lives in prairie dog burrows and hunts prairie dogs for food. Its historical range is nearly identical to that of three prairie dog species-- the black-tailed prairie dog, Gunnison's prairie dog and white-tailed prairie dog.

Prairie dogs were formerly abundant and may have supported as many as 5.6 million black-footed ferrets in the late 1800s [2]. They declined precipitously due to conversion of grasslands to agriculture and development, killing for sport, and large-scale poisoning to eliminate reduction in livestock and agriculture industry profits. Prairie dogs are now absent from an estimated 90 to 95 percent of their historically occupied area.

Ferrets declined in parallel to prairie dogs [1]. Of the approximately 130 counties and provinces where ferrets were found since 1880, only 10 were known to have ferrets by the 1960s [1]. In 1971, six ferrets were caught and removed from a declining population in South Dakota in a first effort at captive breeding. The effort was unsuccessful and the last captive ferret died in 1979. Following this loss, the black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct throughout North America.

In 1981 a tiny, relic population was discovered in a prairie dog colony near Meeteetse, Wyoming [1]. The population declined, so to avert the ferret's extinction, all remaining animals were brought into captivity in 1987. These ferrets are the founders of all subsequent reintroductions.

As of 2008, ferrets had been reintroduced to 18 sites [2]. There were 838 wild ferrets and 422 wild adults which is 28 percent of the recovery plan's goal of 1,500 adult ferrets [2]. In early 2010, the Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that it had reached 47 percent of the goal, which would put the adult population at about 705 and the total population at about 1,410 [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Black-footed Ferret Recovery plan. Denver, Co. 154pp. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plans/1988/880808.pdf

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Black-footed ferret 5-Year review, summary and evaluation. Pierre, S.D. 38 pp. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2364.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Black-Footed ferret. Website http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/blackfootedferret. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[4] Matchett, R. 2006. Personal communication with Randy Matchett, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Senior Biologist, Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, April 16, 2006.

Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/23/1998 |

Range: AK(s), CA(s), FL(o), HI(s), ME(o), MD(o), MA(o), NH(o), NY(o), NC(o), OR(m), RI(o), SC(o), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

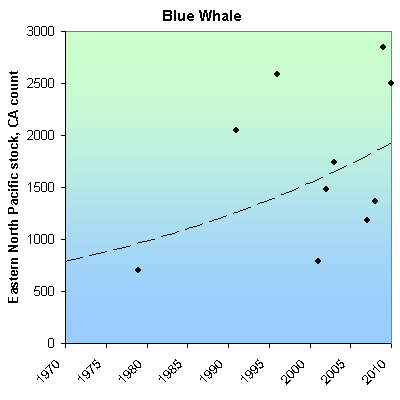

The blue whale population was reduced by as much as 99 percent due to whaling that occurred before the mid-1960s. The number of whales reported off the coast of California, the largest stock in U.S. waters, increased from 704 in 1980 to an estimated 2,497 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal ever known to have lived on Earth [1]. Blue whales are found in all oceans worldwide and are separated into populations from the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere [1]. Each population is composed of several stocks that typically migrate between higher-latitude summer feeding grounds and lower-latitude wintering areas. The largest numbers of blue whales in U.S. waters are within the eastern North Pacific stock. Other U.S. stocks occur in waters off the coast of Hawaii and the Northeast [1].

Pre-whaling blue whale populations had about 350,000 individuals [3]. In 1868, the invention of the exploding harpoon gun made the hunting of blue whales possible and in 1900, whalers began to focus on blue whales and continued until the mid 1960s [1, 3]. During this time, it is estimated that whalers killed up to 99 percent of blue whale populations [3]. Currently, there are about 5,000-10,000 blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere and about 3,000-4,000 in the Northern Hemisphere [3]. Current threats include collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced zooplankton production due to habitat degradation, and disturbance from low-frequency noise [1]. The offshore driftnet gillnet fishery is the only fishery likely to take blue whales, but few mortalities or serious injuries have been observed [2].

EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

The Eastern North Pacific Stock feeds in waters off the coast of California from June to November and then migrates south to Mexico (sometimes going as far south as Costa Rica) in winter/spring [2]. Recently, blue whales seen off the coast of Alaska were photo-matched to photos from the Southern California area, indicating that California animals now migrate as far north as Alaska [4]. This is probably a reestablishment of a traditional migratory route [4]. The number of whales reported off the coast of California increased from 704 in 1979/80 to 2497 in 2010 [2, 11]. It is not certain if the overall increasing trend indicates a growth in the size of the stock, or just increased use of California waters [2], but in general, the stock is thought to have increased [1]. Because this is the largest stock in U.S. waters, it dominates the trend of the species in U.S. waters.

WESTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

Blue whales feeding along the Aleutian Islands are probably part of a central western North Pacific stock that is thought to migrate to offshore waters north of Hawaii in winter [5]. Sightings of blue whales in Hawaiian waters are infrequent, although acoustic recordings indicate that blue whales occur there. There are no estimates of population size for this stock [5]. No blue whales were sighted during aerial surveys of Hawaiian waters conducted from 1993 to 1998 or during shipboard surveys conducted in the summer/fall of 2002 [5]. In 2004, three blue whales were seen in the western Aleutians, the first U.S. sightings of blue whales from this western North Pacific population in several decades [6]

NORTH ATLANTIC STOCK

The blue whale is an occasional visitor along the Atlantic coast of the Northeast [7]. Sightings of blue whales off Cape Cod, Mass., in summer and fall may represent the southern limit of the feeding range of the western North Atlantic stock that feeds primarily off the Canadian coast [7]. Blue whales have been sighted as far south as Florida, however, and the actual southern limit of this stock’s range is unknown [7]. Because blue whales are not frequently seen in U.S. Atlantic waters, there are insufficient data to determine the stock's population trend [7]. In 1997, the total number of photo-identified individuals for eastern Canada and New England was 352 [1].

CITATIONS

[1] NMFS. 1998. Recovery plan for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Prepared by Reeves R.R., P.J. Clapham, R.L. Brownell, Jr., and G.K. Silber for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 42 pp.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] American Cetacean Society. 2005 American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Website http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bluewhl.htm (accessed on 11/30/05).

[4] NOAA. Fisheries. 2004. NOAA Scientists Sight Blue Whales in Alaska. Press Release 7/27/2004.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[6] Rankin, Barlow and Stafford. (in press) Marine Mammal Science.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2002. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised Jan. 2002. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2007. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2008. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] NOAA Fisheries. 2009. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[11] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: AK(s) ---

SUMMARY

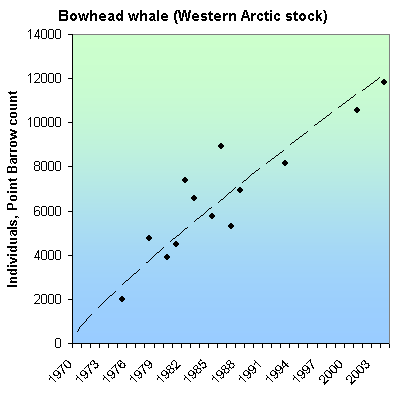

Bowhead whales in the Western Arctic were severely depleted by commercial whaling which reached a peak between 1898-1919. Whaling was banned in 1946. They are currently threatened by increased oil and gas drilling and global warming. Approximately 3,000 bowheads remained when commercial whaling ceased. Following Endangered Species Act listing in 1970, the Western Arctic population increased from 5,189 in 1978 to 11,836 in 2004. The population is likely larger today.

RECOVERY TREND

The bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) is found only in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters [1] and is the only baleen whale to spend its entire life near sea ice without migrating to temperate or tropical waters to calve [2].

For management purposes, five stocks of bowhead whales are recognized [3]. Four small stocks (made up of only a few tens to a few hundred individuals) occur in 1) the Sea of Okhotsk, 2) Davis Strait, 3) Hudson Bay, and 4) the offshore waters of Spitsbergen [3]. The fifth and largest stock, and the only one found within U.S. waters, is the Western Arctic stock, also know as the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock or Bering Sea stock [3]. However, recent evidence suggests that the Davis Strait and Hudson Bay stocks (also known as Western Greenland and Eastern Canada stocks) form a single genetic group and may be comprised of over 1,000 whales [8].

All stocks were severely depleted during intense commercial whaling prior to the 20th century [3].

WESTERN ARCTIC STOCK

The majority of whales in the Western Arctic stock migrate annually from wintering areas in the northern Bering Sea, through the Chukchi Sea in the spring, to the Beaufort Sea where they spend much of the summer before returning again to the Bering Sea in the fall to overwinter [3].

This stock contains over 90 percent of remaining bowhead whales [4] and is making significant progress toward recovery [5].

In the Bering Sea, commercial bowhead whaling occurred primarily from 1898-1919 [3]. It is estimated that whalers killed 18,684 bowheads there, reducing the population from 10,400-23,000 to just 3,000 before whaling was banned in 1946 [1, 3]. They may have driven a distinct, non-migratory stock extinct [5].

Migrating whale counts off Point Barrow indicate the population grew at an annual rate of 3.4% between 1978 and 2001, increasing from 5,189 to 10,545 whales [7]. These counts exclude a much smaller, unknown number of non-migrating whales. The most recent estimate, using a different method, shows a 2004 population of 11,836 whales.

Native subsistence hunts have been permitted since 1977, with annual take ranging from 14-72 whales [3]. The recent harvest rate has been 40 whales per year with another ten or more struck and lost.

The bowhead whale is currently threatened by Western Arctic oil and gas development which brings increased ship traffic, water pollution, and noise pollution from offshore drilling rigs and seismic surveys [3]. Compared to the Gulf of Mexico, the Western Actic has not had a large amount of offshore oil and gas drilling. However, the Bush and Obama administrations issued regional policy and specific drillling decisions which if effected, will substantially increase oil and gas operations in the future.

Bowheads are also threatened by loss of sea ice and other ecosystem changes caused by global warming.

CITATIONS

[1] American Cetacean Society. 2004. Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus) Fact Sheet. Available at <http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bowhead.htm> Revised 3/2004.

[2] Caroll, G. 1994. Bowhead Whale. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Website <http://www.adfg.state.ak.us/pubs/notebook/marine/bowhead.php> accessed March, 2006.

[3] NOAA Fisheries. 2003. Stock Assessment Report. Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus): Western Arctic stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, DC.

[4] National Audubon Society. 1992. Bowhead Whales in Beringia Natural History Notebook Series. Anchorage, AK. Available at <http://www.nps.gov/bela/html/bowhead.htm>.

[5] Shelden, K. E. W. and D. J. Rugh, 1995. The Bowhead Whale, Balaena mysticetus: Its Historic and Current Status. Marine Fisheries Review 57(3-4):1-20.

[7] Alaska Fisheries Science Center. 2010. Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus): Western Arctic Stock. In Alaska Marine Mammal Stock Assessments, 2010. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-223. Available at http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/sars/ak2010.pdf

[8] Alaska Fisheries Science Center. 2011. Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus): Western Arctic Stock (July 2011 draft). In Alaska Marine Mammal Stock Assessments, 2011 (July 2011 draft). Available at http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/sars/ak2011_draft.pdf

California bighorn sheep (Sierra Nevada DPS) (Ovis canadensis sierrae)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 8/5/2008 | Listed: 4/20/1999 | Recovery plan: 9/24/2007 |

Range: CA(b) ---

SUMMARY

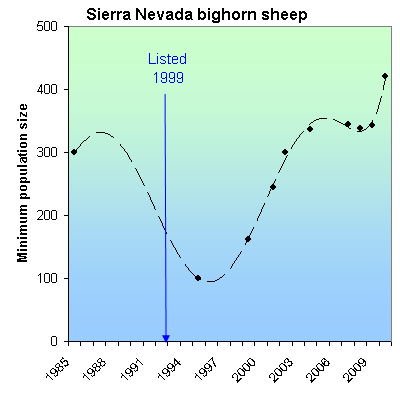

The Sierra Nevada big horn sheep declined due to hunting, disease, introduction of domestic sheep, habitat loss and disturbance. It's historic population of more than 1,000 sheep declined to 300 in 1985 and 100 in 1995 prior to its emergency listing as an endangered species in 1999. Since then its population increased to at least 420 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae) formerly included 20 subpopulations on the eastern slope of California's Sierra Nevada, and at least one subpopulation on the western slope [1]. The historic population size is not well known, but has been estimated at 1,000 or more individuals [5]. It began declining in the mid-1800s due to hunting, disease and the introduction of domestic sheep. About half the subpopulations were gone by the early 1900s. The species continued dwindling to five populations in the 1950s and two in the 1970s [2].

The population was estimated at 250 in 1978 on Mount Williamson, Mount Baxter, and Sawmill Canyon, and 300 in 1985 (mostly In Mount Baxter and Sawmill Canyon) [1, 3, 4]. Thereafter it plunged to a historic low of 100 in 1995. After being listed as endangered in 1999 on an emergency basis, the bighorn's population increased to a minimum of about 350 in 2004, remained at this level through 2009, then increased to 420 in 2010 [5, 6, 7].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Draft Recovery Plan for the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. xiii + 147 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. Final rule to list the Sierra Nevada Distinct Population Segment of the California Bighorn Sheep as Endangered. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, January 3, 2000 (65 FR 20).

[3] Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation. 2000. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Population Status, Census Work 1995 On. www.sierrabighorn.org/endanger/population_status.htm

[4] Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation. 2002. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep 2002 Update, Herds Continue to grow. www.sierrabighorn.org/endanger/2002%20update.htm

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Recovery Plan for Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep. Portland, OR. xiv + 199 pp.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis californiana (=Ovis canadensis sierrae) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Portland, OR. 41 pp.

[7] Stephenson, T. R., et al. 2012. 2010-2011 Annual Report of the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program: A Decade in Review. California Department of Fish and Game.

Columbian white-tailed deer (Douglas County DPS) (Odocoileus virginianus leucurus (Douglas County DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 6/14/1983 |

Range: OR(b) ---

SUMMARY

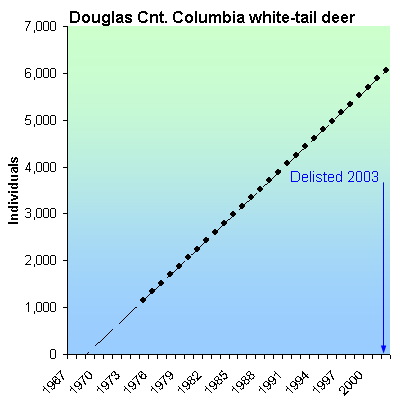

The Columbian white-tailed deer was reduced from tens of thousands of deer to two small, populations totaling 200-300 deer in central Oregon and at the mouth of the Columbia River, due to unrestricted hunting and the loss of riparian and woodland forests. It was listed as endangered in 1967. Due to habitat protection and prohibition on killing, the Douglas County population in central Oregon grew from an estimate 1,200 deer in 1975 to over 6,000 at the time of its delisting in 2003.

RECOVERY TREND

The Columbian white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus leucuruswas) was once considered abundant in the Willamette, Columbia and Umpqua river valleys [1]. Populations of this subspecies once numbered in the tens of thousands, but by the early 1900s the clearing of riparian lands for agriculture and unrestricted hunting drastically reduced populations [1]. By 1940, only two small disjunct populations remained: a population of 200 to 300 in Douglas County, Ore. and a population of 500 to 700 animals along the lower Columbia River in Oregon and Washington [2].

These two populations were listed as separate distinct population segments under the Endangered Species Act: the Columbia River population, and the Douglas County population [2].

In the 1930s, the Douglas County Columbian white-tailed deer population was estimated at 200 to 300 individuals occupying a range of only about 31 square miles [2]. Following its listing as an endangered species in 1967, it grew from from an estimate 1,200 deer in 1975 to over 6,000 at the time of its delisting in 2003 [2]. During this period its range expanded northward and westward, covering approximately 309 square miles by 2003 [2].

CITATIONS

[1] Pacific Biodiversity Institute. 2001. Columbian white-tailed deer. Website <http://www.pacificbio.org/ESIN/Mammals/ColumbiaWhiteTailedDeer/columbiawhitetaileddeerpg.html> accessed May, 2006.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Rule to Remove the Columbian White-Tailed Deer From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 68 FR 43647 43659.

Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 6/8/1993 |

Range: DE(b), MD(b), PA(b), VA(b) --- NJ(x)

SUMMARY

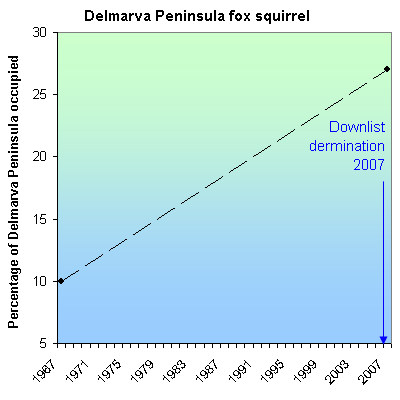

Logging and conversion of forests to farms and developments destroyed much of the Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel's habitat. The squirrel remains threatened by ongoing habitat loss, car strikes and rising sea levels due to global climate change. At the time of listing in 1967, the squirrel occupied only 10 percent of the Delmarva Peninsula. As of 2007, its likely occupied range had expanded to 27 percent of the peninsula. In addition, 11 of 16 translocations have been successful.

RECOVERY TREND

The Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereusis) is a large, heavy-bodied tree squirrel with an unusually full, fluffy tail [1]. Historically, it occurred in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, south-central New Jersey, eastern Maryland, and the Virginia portion of the Delmarva Peninsula [2]. Because the species' habitat requirements are somewhat specific, requiring mature park-like forests, it is likely that populations were scattered and discontinuous. As forests were logged or converted to farms, they became unsuitable for the fox squirrel. As forests regrew, they were cut again before the mature forest required by fox squirrels could develop. By the turn of the century, the Delmarva fox squirrel had disappeared from New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Virginia, and by 1936, it disappeared from Delaware as well.

At the time of its listing as endangered in 1967, the Delmarva fox squirrel occurred in about 10 percent of its former range in four eastern Maryland counties (Kent, Queen Anne’s, Talbot and Dorchester) [1]. As of 2007, the known range of the squirrel covered 27 percent of the Delmarva Peninsula [3]. This represents the total acreage where the squirrels are likely to occur, delineated as the area within three miles of all occupied habitat. The known area of occupied habitat is now more than 25,000 acres larger than it was in 1998, and some of the newly discovered populations significantly extend the periphery of the range known at the time of listing. Using a total area of occupied habitat of 128,434 acres and density estimates, it is estimated that the total population size is now 20,000 to 38,000 squirrels.

Starting in 1968, efforts were made to translocate fox squirrels into unoccupied habitat. As of 2007, 11 of 16 translocations were considered to be successful based on recovery plan criteria [3]. After approximately 25 years, almost 70 percent of the original release sites have persisting populations of Delmarva fox squirrels, with expansion indicated at the majority of sites. Of the unsuccessful translocation efforts, three were thought to have failed by 1993 (Nassawango, Fairhill and Chester). A fourth (Brownsville, Va.) began with a substantial number of animals, but although a few persisted at this site for an extended period, there was no evidence of reproduction. The most recent loss was the population at Assawoman, which was started with 13 animals and monitored as a benchmark site. Despite comparatively low numbers, reproduction was occurring and the

population persisted for about 15 years; however, Assawoman was not supplemented with additional animals, and this reintroduction is now considered unsuccessful

according to the recovery plan criteria. The population on Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge was not counted as one of the 16 translocations; however, it started from an historic translocation conducted in the 1920s by the hunt club that owned the property at the time. The population thrived on this relatively small island for many years and was a source of animals used to establish and supplement the translocated population at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Recent trapping evidence and observations by refuge staff indicate that this population has diminished to a few individuals at most, and it remains to be seen whether this population will blink out or bounce back [3].

The 1993 recovery plan specified a series of benchmark sites where squirrels were to be monitored for a minimum of seven years, using winter nest box checks and some trapping, in order to better understand the subspecies’ population dynamics. The seven sites included Blackwater, Chincoteague, and Prime Hook national wildlife refuges; Hayes Farm; Lecompte and Wye Island wildlife management areas, , and Assawoman Wildlife Area. Only four of the sites, Blackwater, Hayes Farm, Lecompte, and Wye Island, are part of the remnant distribution of this species; the others are translocation sites. Monitoring results showed the squirrels to be present and breeding at all benchmark locations during the seven-year study period; however, since the conclusion of the benchmark evaluation, the Assawoman translocation has been deemed a failure [3]. Despite this, the 2007 Five-Year Review recommended downlisting [3].

Current threats to the Delmarva fox squirrel include development, timber harvest, short-rotation pine forestry, forest conversion to agriculture, and rising sea levels due to global climate change [1,3]. Because much of the squirrel’s occupied habitat is on privately owned lands, the success of conservation efforts will be largely dependent on management practices on these lands. Small populations are also very susceptible to extirpation.

In the 2007 Five-Year Review, the Service recommended downlisting the squirrel from “endangered” to “threatened” [3]. However, due to ongoing threats to the species and lack of reliable quantitative long-term population data, it would be premature to downlist the squirrel.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Delmarva Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereus) Recovery Plan, Second Revision. Hadley, Massachusetts. 104 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984: Proposed Determination of Experimental Population Status for Introduced Population of Delmarva Fox Squirrel; Federal Register (49:13556-13558).

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Delmarva Peninsula Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Chesapeake Bay Field Office, Annapolis, Maryland. 56 pp.

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 7/30/2010 |

Range: AL(o), AK(s), CA(s), CT(s), DE(s), FL(s), GA(s), HI(s), LA(o), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(o), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), OR(s), PA(s), RI(s), SC(s), TX(o), VA(s), WA(s) ---

SUMMARY

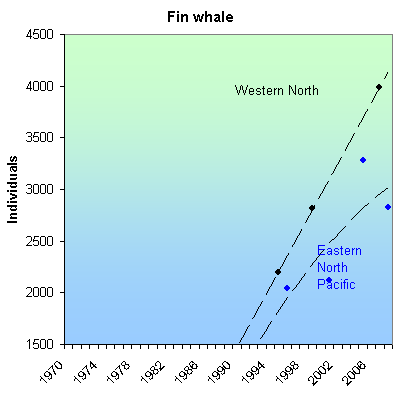

Fin whales were hunted in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century, causing population decline. Ongoing threats include illegal and legal whaling, vessel collisions, fishing gear entanglement, reduced prey and noise. Total population size is unknown, but both the North Atlantic and North Pacific populations increased between 1995 and 2009.

RECOVERY TREND

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and southern oceans mix rarely, if at all. For management purposes, the North Pacific is divided into three stocks: 1) the California/Oregon/Washington stock, 2) the Hawaii stock and 3) the Alaska stock [2]. A western North Atlantic stock inhabits U.S. waters along northeastern coasts [3]. Most groups are thought to migrate seasonally, in some cases over large distances [1]. They feed at high latitudes in summer and move to low latitudes in winter. Some groups move over shorter distances and may be resident to areas with a year-round supply of adequate prey.

Fin whales were hunted, often intensively, in all the world's oceans for the first three-quarters of the 20th century [1]. From 1947 to 1987, approximately 46,000 fin whales were taken from the North Pacific [2]. Commercial whaling did not end until 1976 in the North Pacific and 1987 in the North Atlantic. The current status of fin whale populations relative to pre-whaling levels is uncertain.

In the North Pacific, pre-whaling populations were estimated to be between 42,000 and 45,000 [2]. By 1973, the North Pacific population is thought to have been reduced to 13,620-18,680 — less than 38 percent of historic carrying capacity [2].

California/Oregon/Washington Stock

The California/Oregon/Washington stock of the North Pacific is thought to be increasing [5]. Fin whale acoustic signals are detected year-round off Northern California, Oregon and Washington, with a concentration of vocal activity between September and February [2]. Fin whales increased in abundance along the California coast between 1979 and 1996, and based on ship surveys in 2001, they continued to increase. Populations appeared to be increasing monotonically from 1991 to 2001 [5]. In 2001, 3,279 (CV= 0.31) were estimated in California, Oregon and Washington coastal waters [2]. The 2008 population was estimated at 2,825 whales [9].

Alaskan Stock

Since 1999, information on abundance of fin whales in Alaskan waters has improved and although the full range has not yet been surveyed, a rough estimate of the size of the population west of the Kenai Peninsula is 5,703 [6]. Surveys conducted in 1999 and 2000 in the central-eastern Bering Sea and southeastern Bering Sea provided provisional estimates of 3,368 (CV = 0.29) and 683 (CV = 0.32), respectively [6]. One aggregation of fin whales spotted in 1999 involved more than 100 animals [6]. Because historical abundance information is lacking, population trends are difficult to determine [6].

Hawaiian Stock

Fin whales are rare in Hawaiian waters and the stock is thought to be quite small [7]. Over the course of 12 aerial surveys conducted within about 25 nautical miles of the main Hawaiian Islands in 1993-98, only one fin whale was sighted [7]. More recent acoustic data suggest that fin whales migrate into Hawaiian waters mainly in fall and winter [7]. In 2002, a ship survey of the entire Hawaiian Islands resulted in an abundance estimate of 174 (CV=0.72) fin whales [7].

Western North Atlantic Population

Western North Atlantic fin whales off the eastern U.S. coast north to Nova Scotia and the southeastern coast of Newfoundland are considered a single stock [3]. New England waters represent a major feeding ground, and calving is thought to take place along mid-Atlantic U.S. latitudes from October to January. The locations used for calving, mating and wintering for most of the population remains unknown. It is likely that fin whales occurring in the U.S. Atlantic undergo migrations into Canadian waters, open-ocean areas, and perhaps even subtropical or tropical regions. An abundance of 2,200 (CV=0.24) fin whales was estimated from a 1995 line-transect sighting survey that covered waters from Virginia to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. A 1999 estimate of 2,814 (CV=0.21) fin whales, currently considered the best estimate for the western North Atlantic stock, was derived from a line-transect sighting covering waters from Georges Bank to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence [3]. The best estimate of population for this stock in 2007 is 3,985 whales [8]. Although there is little data on population trends, the minimum population estimate reported in NOAA Fisheries Stock Assessment Reports has steadily increased since 1992.

The main direct threat to fin whales today is the possibility of illegal whaling or a resumption of legal whaling [1]. In 2006, Japan announced that it would expand hunts to include fin whales [4]. It expected to harvest 10 fin whales from Antarctic waters [4]. Collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced prey abundance due to overfishing and habitat degradation, as well as disturbance from low frequency noise, are also potential threats [1]. The offshore drift gillnet fishery is the main fishery likely to take fin whales [2].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1998. Draft Recovery Plan for the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Sei Whale (Balaenoptera Borealis). Silver Spring, MD.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Stock Assessment Report. North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis): Western Stock revised Dec., 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic stock. Revised Dec. 2004. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[4] Hans Greimel, Associated Press. 2005. Japan To Double Usual Whale Kill in New Antarctic Hunt, Expanded To Include Fin Whales. Nov. 9, 2005.

[5] Barlow, J. 2003. Preliminary Estimates of the Abundance of Cetaceans along the U.S. West Coast: 1991-2001 Southwest Fisheries Science Center Administrative Report LJ-03-03. Available at <http://swfsc.nmfs.noaa.gov/prd/PROGRAMS/CMMP/default.htm>.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Northeast Pacific stock. Revised 10/21/2004.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Draft Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Hawaiian stock. Revised 3/15/2005.

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised 11/2010.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2011. 2010 Stock Assessment Report. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus): California/Oregon/Washington stock. Revised 1/15/2011.

Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/24/1976 | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 10/3/2001 |

Range: AL(o), CT(o), DE(o), FL(b), GA(b), LA(o), MD(o), MS(o), NY(o), NJ(o), NC(o), RI(o), SC(o), TX(o), VA(o) ---

SUMMARY

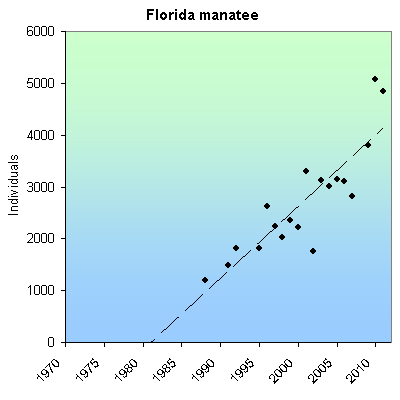

The Florida manatee is imperiled by habitat loss, coastal development, and motor boat collisions. It was listed as endangered in 1967, but range-wide systematic surveys were not instituted until 1991. The manatee increased 227% between 1991 and 2011 (1,478 to 4,834 manatees). Local surveys indicate the manatee has been increasing since the 1970s.

RECOVERY TREND

The Florida manatee (Trichechus manatuslatirotris latirostris) lives in freshwater, brackish and marine environments and inhabits shallow coastal waters, estuaries, bays, rivers and lakes [1]. Florida manatees occur in waters of the southeastern United States, primarily in Florida and southeastern Georgia, but individuals can range as far north as Rhode Island and probably as far west as Texas [2]. During winter, cold water temperatures keep the population concentrated at warm water sites in peninsular Florida [2].

Collisions with boats represent the greatest current threat to Florida manatees but water-control structures also account for significant mortality. Habitat loss caused by residential and commercial development also remains a problem and the loss of warm water refuges could pose a significant threat [2].

Historical data for Florida manatee numbers are poor [2]. Early aerial survey studies conducted in the late 1980s concluded that there were at least 1,200 animals [4]. Beginning in 1991, the state initiated synoptic aerial surveys to count manatees in potential winter habitat during periods of extreme cold weather. Aerial survey results are highly variable however, and results depend on weather conditions [2]. The number of manatees counted increased from 1,478 in 1991 to 4,834 in 2007 [6]. Warm water refuge counts, which are more accurate, also show an increase since the 1970s [2]. An analysis of trends at winter aggregation sites suggests a mean annual increase of 7 percent to-12 percent occurred at sites on the East Coast from 1978 to 1992 [3]. More detailed demographic data is needed, and more widespread accurate surveys must be conducted before population trends can be determined with certainty.

Over the past 25 years, there has been an increase in Florida manatee deaths. It is unclear whether this represents a proportional increase relative to overall population size [2]. This needs further investigation because Florida manatee recovery likely depends on controlling human-caused mortality of adult manatees [2]. "Red tides" caused by the dinoflagellate (Gymnodinium breve) have also resulted in three incidents (1982, 1991 and 1996) of high mortality [2]. Observed declines in the percentage and number of calves seen at power plant aggregation sites is also cause for concern [4].

CITATIONS

[1] Lefebvre, L. W., et al. 1989. Distribution, status, and biogeography of the West Indian manatee. Pages 567-610 in C. A. Woods (editor). Biogeography of the West Indies. Sandhill Crane Press, Gainesville, Florida

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Florida Manatee Recovery Plan, (Trichechus manatus latirostris), Third Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Atlanta, Georgia.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus latirotris) Florida Stock Assessment. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Jacksonville Florida. Revised 1995

[4] Reynolds, J.E., III and J.R. Wilcox. 1994. Observations of Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris ) around selected power plants in winter. Marine Mammal Science 10(2): 143-177

[5] Associated Press. 2007. Report: U.S. may take manatees off endangered list. April 9, 2007.

[6] Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2012. Synoptic aerial surveys (1991-2011). http://myfwc.com/research/manatee/projects/population-monitoring/synoptic-surveys/.

Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 11/1/2008 |

Range: FL(b) --- AL(x), AR(x), GA(x), LA(x), MS(x), SC(x), TN(x)

SUMMARY

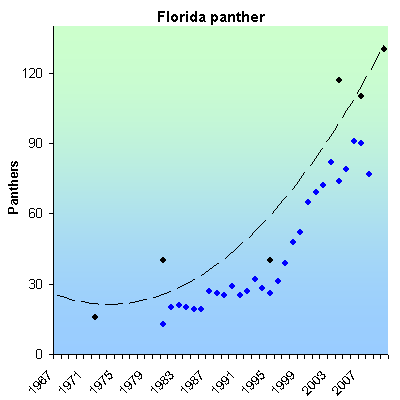

The Florida panther was reduced to near extinction by habitat loss, hunting, persecution, and vehicle collisions. Vehicle collisions, habitat loss and fragmentation, lack of sufficient wildland areas, and in-breeding depression remain current threats. Its population size when listed as endangered in 1967 is unknown, but may have been a little larger than the 30-50 animals recorded throughout the 1980s. The population began to grow after a genetic intervention in 1990s, reaching 130 panthers in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi) formerly ranged from eastern Texas and western Louisiana into the lower Mississippi River Valley and eastward through Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia and parts of Tennessee and South Carolina [1].

Hunting and habitat loss reduced the subspecies to a single population of 30 to 50 adults in south Florida by the late 1980s [2]. This population generally occurs within the Big Cypress Swamp physiographic region and is centered in Collier and Hendry counties [1].

In 1981, two panthers were captured and radio-collared, initiating an extensive monitoring program. More than 116 panthers have been collared since the program’s inception [5]. By 1990, all extensive panther habitats had been explored and few panthers remained uncollared [5].

Between 1981 and 1990, the panther population was static at 30 to 50 adults [5] and showing signs of inbreeding depression expressed through increased genetic defects in the heart and sperm [4]. To increase genetic diversity, eight reproductive females from a closely related subspecies were translocated from Texas in 1995. The population increased 200 percent between the 1995 translocation population and 2003 when it reached 87 individuals [3, 4]. It has continued to grow since then, reaching 97 in 2006 [6], 118 in 2007 [8], and 130 in 2010 [7].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and wildlife Service. 1993. Florida Panther (Felis Concolor Coryi) Species Account. Website < http://www.fws.gov/endangered/i/a/saa05.html> accessed May, 2006.

[2] Lotz, M., D. Land, M. Cunningham and B. Ferree. 2005. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Florida Panther Annual Report 2—4-2005. Available at <http://www.panther.state.fl.us/news/pdf/FWC2004-2005PantherAnnualReport.pdf>.

[3] Gross, L.J. and Comiskey. 2002. ATLSS PanTrack Telemtry Visualization Tool. U.S. Geological Survey Greater Everglades Science Program 2002 Biennial Report. Available at <http://sofia.usgs.gov/projects/atlss/panthers/telvistool_03geerab.html>.

[4] Pimm, S.L., L. Dollar, and O.L. Bass Jr. 2006. The genetic rescue of the Florida panther. Animal Conservation 9(2):115-122.

[5] McBride, R.T. 2001. Current panther distribution, population trends, and habitat use: report of field work: fall 2000 – winter 2001. Report to Florida Panther SubTeam of MERIT, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Florida Ecosystem Office, Vero Beach, Florida. www.panther.state.fl.us/news/pdf/rtm2001.pdf.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Draft 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation for the Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi). Vero Beach, FL.

[7] Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. 2010 . Statement on Estimating Panther Population Size. Available online at http://myfwc.com/news/resources/fact-sheets/panther-population/. Accessed September 19, 2011.

[8] Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. 2009. Annual Report on the Research and Management of Florida Panthers: 2008-2009. Available online at http://www.floridapanther.org/images/FWC_Panther_AR_2008_2009.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2011.

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/28/1976 | Recovery plan: 7/1/1982 |

Range: AL(b), AR(b), FL(o), GA(o), IL(o), IN(o), KS(o), KY(b), MS(o), MO(b), NC(o), OK(o), TN(b), VA(o), WV(s) ---

SUMMARY

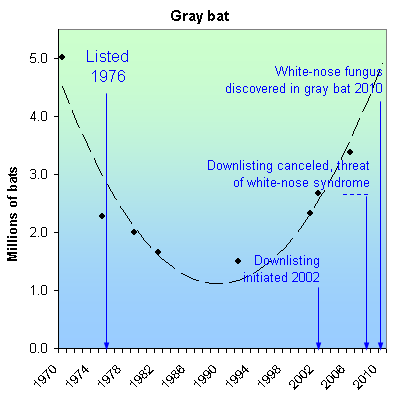

Gray bats declined due to mining, cave disturbance, vandalism, persecution, flooding, deforestation and possibly pesticides. In 2010, they were found with white-nose syndrome, but it is not known if the fungus is lethal to them or not. There were likely at least 5 million gray bats in 1970. At listing in 1976, the gray bat was declining, to a low of 1.5 million bats in 1992. Numbers reached 3.4 million in 2006, the most recent rangewide estimate.

RECOVERY TREND

The gray bat (Myotis grisescens) is one the few North American bats to inhabit caves year-round, and may be the most cave-dependent mammal in the United States [5]. The specificity of these bats' needs, the rarity of caves that can satisfy them, and a growing human population that increasingly seeks out those very same caves thrust the gray bat into a century-long extinction trajectory from which it only recently escaped.

The discovery of white-nose syndrome in gray bats in 2010, however, threatens to reverse the dramatic population gains of the past two decades.

NATURAL HISTORY

Gray bats require exceptionally cold caves during winter hibernation [1]. The temperature must be between 42 degrees and 52 degrees. One or more vertical shafts must descend below the level of the entrance so that as cold air flows in, it becomes trapped, keeping the cave a steady temperature. Hibernacula often have multiple entrances to facilitate air flow.

As fewer than 5 percent of caves in the bat's range have these properties, large numbers of wintering bats crowd into a very small number of caves, some of them traveling hundreds of miles from their summer roosts to find them [1]. Since at least the 1960s, 95 percent of all gray bats winter in just nine caves. Historically, large hibernacula consisted of more than a million bats; in recent years, they support hundreds of thousands.

Females enter hibernation immediately after copulating (usually September or October) but do not become pregnant until emerging from hibernation in the spring. Males, which are generally more plastic in their roosting needs, remain active until entering hibernation in November.

In the spring, pregnant females disperse to very specific maternity caves where they simultaneously give birth to and raise one pup each. (Males and yearling females disperse to smaller, nearby caves.) Pup survival is closely related to the temperature of the maternity site within the maternity cave. The warmer the site, the better: If it is not between 57 degrees and 77 degrees, pup mortality is elevated. Gray bats help maintain the proper temperature by seeking out caves with domed, heat-trapping ceilings and heating them with their own bodies. If the species is healthy enough to have tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of bats in a single maternity colony, their bodies will produce a substantial amount of heat; and if the cave is structured to retain that heat, the maternity site will remain a steady, warm temperature.

Gray bats forage over rivers, streams, lakes and reservoirs, primarily capturing aquatic insects such as mayflies, caddisflies and stoneflies, but also eating beetles and moths when they cross paths. Most summer caves are within 2.5 miles of a river or lake, further limiting the bats' availability, though some bats travel as far as 22 miles to forage if needed.

THREATS

The gray bat is something of wilderness species, not tolerating human disturbance very well [1]. If humans disturb a maternity roost, it can cause mass mortality of pups, which fall to the cave floor as the startled females withdraw or take flight. Both maternity roosts and hibernacula may be abandoned in response to disturbance.

Caves may be rendered unusable or less able to support gray bat needs if protective vegetation around the entrance is removed, airflow is disturbed by barriers, ingress and egress routes are altered, or the cave's structure or temperature is altered.

In addition to these common, often catastrophic — but not necessarily malicious — impacts, humans have killed large numbers of gray bats for sport, vandalism, or in the mistaken belief that bats are harmful to humans and their crops and pets.

The gray bat's evolved foraging, maternity and roosting strategies intersect with the region's small number of suitable caves to cause a very large portion of the species to inhabit a very small number of roosts. If those roosts are disturbed, even by relatively minor actions, significant portions of the population can be quickly lost. Thus one of the first monographs on the gray bat's decline declared that the "concentration of such a large proportion of the known population into so few caves constitutes the real threat to their survival" [10].

As the human population within the gray bat's range has grown, it has increasingly come into contact with formerly remote bat caves, causing gray bats to withdraw to more remove caves. Today, however, there are few caves left to withdraw to, so it is imperative that all occupied and important caves be protected from disturbance.

If gray bats decline to very low numbers, there will not be enough bats to maintain high maternity roost temperature, which, in a positive feedback loop, will increase pup mortality, further suppressing the population.

In 2010, white-nose syndrome was found in a gray bat hibernaculum in Shannon County, Mo. [14]. This is an enormous threat because it could spread very quickly to the great majority of the species. The bats, however, were not obviously distressed and it is not yet known if white-nose is lethal to them.

RANGE

Gray bats are primarily found in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee, with smaller populations found in adjacent states, including a growing population in Indiana [1]. Ninety-five percent of bats hibernate in 17 caves in Tennessee (5), Missouri (4), Arkansas (5), Kentucky (3) and Alabama (1).

POPULATION TRENDS

The historic gray bat population size is unknown. Based on reported regional declines of 70 percent to 76 percent from maximum historic levels by 1976-1980 [4, 8], and an estimated range-wide population size of about 2 million in 1979 [8], we estimate the historic population to have been at least 9.5 million bats. It may have been much larger.

Though the scale has not been quantified, the gray bat's decline is believed to have begun in the 19th century with the advent of commercial mining of saltpeter, onyx and other cave minerals [5]. By the beginning of the 1960s, its status was of enough concern for scientists to warn that gray bats were especially vulnerable to human disturbance [7]. By the end of the decade, scientists were predicting the animal's extinction: "in the last few years human disturbance has threatened the very existence of the species…M. grisescens is destined to continue a rapid decline in numbers and probably faces extinction" [6].

The extinction trajectory continued during the 1970s. Using a "conservative" method he suggested would produce "a gross underestimate of true population losses," Merlin Tuttle documented a 54 percent decline of the 22 "healthiest" maternity caves in Alabama and Tennessee between 1970 and 1976 [8]. As the caves had declined 47 percent before his study started, the total decline from historic levels was 76 percent. A similar level of decline (70 percent from historical levels) was documented in nine major maternity roosts in Missouri by 1980 [4].

Only seven of the 22 caves studied by Tuttle were at their maximum historic level in 1970. This was reduced to four by 1976. The largest maternity colony — which was also the species' largest remaining maternity colony — numbered 111,400 bats in 1970. By 1976, it had declined by 95 percent to 6,000 bats.

Where others viewed the gray bat as a near lost cause, Tuttle found hope in the upswell of conservation actions since the bats listing as an endangered species in 1976:

"Since the gray bat was listed as endangered, encouraging progress has been made. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service is purchasing the major gray bat hibernating cave reported by Hall and Wilson (1966) in Kentucky as well as the most important known summer cave (no. 11 in this paper), and is considering other important acquisitions. It also has fenced and posted cave 15 of this study on the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge…Following only 2 years of strict protection from human disturbance, this colony has now returned to maternity status and has increased to more than 19,000 bats….Although recent decline of gray bats has been precipitous there is no reason to believe that this trend cannot be reversed if adequate measures are taken to prevent human disturbance and vandalism." [8].

The gray bat continued to decline, however, leading the federal gray bat recovery team to warn in 1984 that if current trends continued, the species would be reduced to 100,000 individuals by 2000, triggering an irreversible extinction spiral because maternity roosts would be too small to successfully raise young [5].

The declines continued through 1992, when the gray bats reached a low point of 1.5 million individuals [13]. Thereafter the population rapidly increased to 3.4 million in 2006 [11, 12, 1]

DOWNLISTING CONSIDERATION

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced in 2002 that it intended to downlist the gray bat from endangered to threatened status [15]. Downlisting was widely supported by scientists due to the large upswing in bat numbers, the many protections that had been instituted to purchase, protect and manage many important caves, a commitment to continued monitoring, and the sense that these efforts have become sufficiently institutionalized within federal and state agencies to continue indefinitely.

While the Fish and Wildlife Service was examining the bat's population and management status in consideration of downlisting, white-nose syndrome appeared in the New York and spread rapidly north, south and east, killing some 7 million bats by 2011. In its 2009 “Five-Year Review,” the agency responded by putting the downlisting process on hold:

"Despite the achievements in recovery for this species, the potential threat of white-nose syndrome to populations of Myotis grisescens is of such a magnitude that any possible recommended changes in the future on the classification of this species should be withheld until more can be learned about WNS and its possible adverse impact on gray bat. If WNS spreads to populations of gray bats and results in mortality rates reported elsewhere in the northeastern U.S., the vulnerability of the species to extinction would be high..."

The following year, white-nose would be found in a gray bat hibernaculum and on five of the bats themselves [14]. While the potential for catastrophe is great — likely much greater for the gray bat than any other species — it is not yet known if white-nose is lethal or significantly harmful to it. If the fungus is lethal at levels it has been to some other bats, it could quickly drive the gray bat extinct.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Five Year Review of the Gray Bat (Myotis grisescens). Columbia, MO. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2625.pdf

[2] Ellison, L.E., T. J. O’Shea, M.A. Bogan, A.L. Everette and D.M. Schneider. 2003. Existing data on colonies of bats in the United States: Summary and analysis of the U.S. Geological Survey’s bat population database. Pages 127-237 in T.J. O’Shea and M.A. Bogan, eds.: Monitoring trends in bat populations of the United States and territories: problems and prospects. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Information and Technology Report, USGS/BRD/ITR-2003-0003. 274 pp.

[3] Sasse, D.B., R.L. Clawson, M.J. Harvey, and S.L. Hensley. 2007. Status of populations of the endangered gray bat in the western portion of its range. Southeast. Naturalist 6(1):165-172.

[4] Elliott, W.R. 2008. Gray and Indiana bat population trends in Missouri. Pages 46-61 in Proceedings of the 18th National Cave & Karst Management Symposium, W.R. Elliott, ed; Oct. 8-12, 2007. National Cave and Karst Management Symposium Steering Committee. 320 pp. www.utexas.edu/tmm/sponsored_sites/biospeleology/pdf/2008%20elliott%20bats.pdf

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982. Gray bat recovery plan. Minneapolis, MN. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/820701.pdf

[6] Barbour, R.W., and W.H. Davis. 1969. Bats of America. University of Kentucky Press, Lexington, 286 pp.

[7] Manville, R.H. 1962. A plea for bat conservation. Journal of Mammalogy. 43:571.

[8] Tuttle, M. 1979. Status, causes of decline, and management of endangered gray bats. Journal of Wildlife Management 43:1-17.

[9] Harvey, M.J. 1992. Bats of the eastern United States. Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Little Rock.

[10] Mohr, C.E. 1972. The status of threatened species of cave-dwelling bats. Bull. Natl. Spe1eo1. Soc. 34:33-47.

[11] Martin, C.O. 2007. Assessment of the population status of the gray bat (Myotis grisescens). Status review, DoD initiatives, and results of a multi-agency effort to survey wintering populations at major hibernacula, 2005-2007. Environmental Laboratory, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center Final Report ERDC/EL TR-07-22. Vicksburg, Mississippi. 97 pp. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA473199

[12] Harvey, M.J., and R.R. Currie. 2007. Gray bat (Myotis grisescens) status review. Unpublished working paper, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Asheville, NC. March 2007.

[13] Harvey, M.J. 1992. Bats of the eastern United States. Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Little Rock.

[14] Traylor-Holzer, K., Tawes, R., Bayless, M., Valenta, A., Rayman, N., and Songsasen, N. (eds.). 2010. Insectivorous Bat Captive Population Feasibility Workshop Report. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN.

[15] Department of Interior. 2002. Semiannual Regulatory Agenda. December 9, 2002 (67 FR 74583).

Gray whale (Eastern North Pacific DPS) (Eschrichtius robustus pop. 3)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: none |

Range: AK(b), CA(b), OR(b), WA(b) ---

SUMMARY

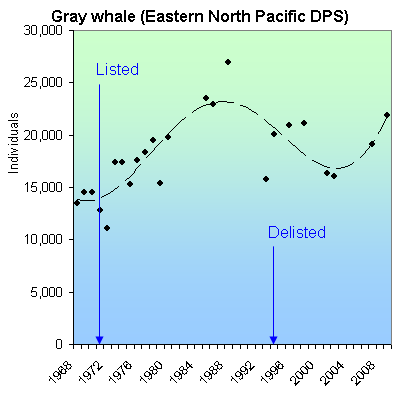

Gray whales declined precipitously due to whaling, becoming extinct in the Atlantic, endangered in the Eastern North Pacific and extremely endangered in the Western North Pacific. They are threatened by oil and gas drilling and coastal development. In 1968, there were 13,426 Eastern North Pacific gray whales. The species was was listed as endangered in 1970 and removed from the list in 1994 when the population reached 20,103 whales. The 2009 population was estimated to be 21,911.

RECOVERY TREND

The Eastern North Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) migrates along the West Coast from summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi seas to nearly landlocked lagoons and bays along the west coast of Baja California where calves are born from early January to mid-February [2].

It historic population size has been estimated at about 19,500 [1] based on log books and historical accounts [4]. However, recent genetic analysis indicates a historic population on the order of 96,000 whales (76,000–118,000) [3].

Early indigenous whaling impacts were likely substantial to this near-shore species, especially to resident populations [4], but have not been quantified. The added pressure of commercial whaling however, drove the species to near extinction in the 19th and 20th centuries. Between 1846 and 1900, commercial whalers killed nearly 9,000 gray whales and indigenous hunters about 6,000 [1]. After 1900, the two groups killed another 11,500 whales, for a total of 27,000 between 1846 and 1946.

Commercial whaling was prohibited in 1946 and indigenous whaling was greatly reduced. At the time of its listing as an endangered species in 1970, the gray whale was extinct in the Atlantic, at low levels in the Eastern North Pacific, and at extremely low levels in the Western North Pacific [2].

Between 1968 and 1988, the Eastern North Pacific gray whale grew from 13,426 whales to a post-exploitation peak of 26,916 [1]. It declined to 20,103 whales by 1994 when it was delisted, remained stable for a few years, and then declined again to about 16,000 whales in 2001 and 2002. These declines were preceded by an unprecedented number of whale strandings in 1999 (273) and 2000 (355), greatly exceeding the previous average (38). The stranding were also unusual in being dominated by adults and subadults (>60%) rather than calves. The whales were visibly emaciated, possibly due to poor feeding conditions (i.e. extensive ice cover) in their wintering grounds.

Recent population estimate are in dispute. The 2010 reanalysis cited for all population numbers in this account [1], indicates the stock grew to 21,911 whales in 2009.

The Western North Pacific gray whale remains listed as an endangered foreign species. It has not recovered since listing and today is comprised of less than 100 whales which are highly endangered by oil and gas drilling proposals in Asia and Russia.

CITATIONS

[1] Punt, A.E. and P.R. Wade. 2010. Population Status of the Eastern North Pacific Stock of Gray Whales in 2009. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-207, 43 p.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service. 1994 Final Rule to Remove the Eastern North Pacific Population of the Gray Whale From the List of Endangered Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 31094.

[3] Alter, S.E., E. Rynes and S.R. Palumbi. 2007. DNA evidence for historical population size and past ecological impacts of gray whales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:15162–15167.

[4] Pyenson, N.D. and D.R. Lindberg. 2011. What Happened to Gray Whales during the Pleistocene? The Ecological Impact of Sea-Level Change on Benthic Feeding Areas in the North Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE 6(7): e21295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021295.

Gray wolf (Northern Rockies DPS) (Canis lupus (Northern Rockies DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 8/3/1987 |

Range: ID(b), MT(b), eastern OR(b), eastern WA(b), WY(b), northern UT(o)

SUMMARY

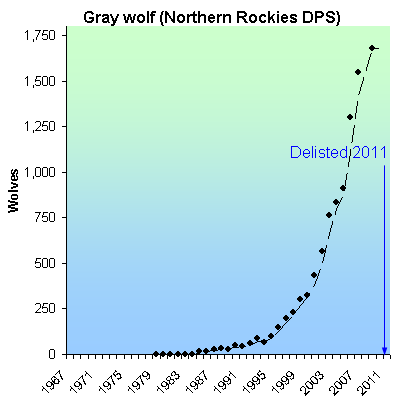

Gray wolves were purposefully hunted, trapped and poisoned to near extinction in the western United States, often by the federal government or with the encouragement of private and state bounties. By 1973, no wild wolves remained in the region. They were listed as endangered in 1967 and began recolonizing the Northern Rocky Mountains from Canada in the early 1980s. Due to prohibition of killing, habitat protection, and reintroductions, the population grew rapidly, was downlisted in 2003, reached 1,679 wolves by 2009, and was delisted in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The Northern Rocky Mountains gray wolf (Canis lupus pop.) historically occurred throughout Idaho, the eastern third of Washington and Oregon, all but the northeastern third of Montana, the northern two-thirds of Wyoming, and the Black Hills of South Dakota [1]. As early American settlers began moving west, populations of the gray wolf’s important prey species were over-hunted, causing the wolves to resort to hunting sheep and cattle. As a result, bounty hunting of wolves began in the 19th century and continued through as late as 1965. Around the turn of the century some population control measures were attempted in Yellowstone National Park that led to increased numbers of gray wolves in the area. In response, however, people began killing large numbers of wolves [1]. Beginning in 1912 a minimum of 136 wolves and 80 pups were killed each year and by 1920, only 30 to 40 wolves persisted in this area [1]. By 1973, gray wolves were exterminated from the western lower 48 states and existed only in northeastern Minnesota and Isle Royal, Mich. [2].

Protection of gray wolves was not initiated until the enactment of the Endangered Species Act. By this time gray wolves no longer occurred in the western United States except for the occasional dispersion of Canadian animals into Montana and Idaho that failed to survive long enough to reproduce [3]. Successful recolonization of gray wolves into the Rocky Mountain region did not occur until the early 1980s. Around this time, the Rocky Mountain Gray Wolf Recovery Team was organized with the intent of developing standard observation methods for studying and monitoring the wolves. In 1987, a recovery plan was published. Around this time, the status of the Rocky Mountain Gray wolf was still quite precarious. In Montana, from 1985 to 1986 roughly 15 to 20 wolves were believed to occur near Glacier National Park. In Wyoming from 1982 to 1985, 15 wolves were reported at Yellowstone National Park, and the same number were believed to occur in Idaho in 1986 [1].

Regular monitoring of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf population did not occur until 1995, at which time there were an estimated 14 wolves in Montana and 15 in greater Yellowstone. By 2000, there were an estimated 65 wolves in Montana, 118 in Yellowstone, and 141 in central Idaho [4]. In 2004, a recovery update of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf was released, providing information regarding the status of the gray wolf at three designated recovery areas: the Northwestern Montana Recovery Area (NWMT) in Montana and the Northern Idaho panhandle; the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA), which includes Wyoming and adjacent parts of Idaho and Montana; and the Central Idaho (CID) area covering central Idaho and adjacent parts of southwest Montana. As of 2004, 16 packs containing 59 wolves were documented at NWMT [3]. In the GYA, 171 wolves in 16 packs inhabited the Wyoming portion and 17 packs occurred in the Montana region. In the CID 64 wolves in 40 groups and as individuals were monitored [3]. The total population of free ranging Rocky Mountain Gray wolves for 2004 was estimated at 59 in Montana, 324 in Greater Yellowstone, and 422 in Central Idaho. In 2005 population estimates were 93, 294, and 525 respectively [4]. In 2009 the population of wolves in the Northern Rockies was about 1,679, up from 1,545 in 2007 and 1,300 in 2006 [4].

The U.S. Fish and Wildife Service delisted the Northern Rockies gray wolf in 2008, but the decision was objected to by conservationists who argued that the recovery plan goal was outdated, and insufficient to remove the threat of extinction because it did not require a large enough or well-connected enough wolf meta-population. In 2011, with encouragement from the Department of Interior, Congress for the first time in the history of the Endangered Species Act, overruled the courts and order the delisting of the Northern Rockies gray wolf without biological or legal review [7].

CITATIONS

[1] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1987. Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Denver, CO. 119pp

[2] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Gray Wolf. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Revised May, 2004.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nez Perce Tribe, National Park Service, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Idaho Fish and Game, and USDA Wildlife Services. 2005. Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Helena, MT. 72pp. Available at <http://westerngraywolf.fws.gov/annualreports.htm>

[4] International Wolf Center. 2011. Gray Wolf Population Trends in the Contiguous United States. Website <http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/wow/regions/United_States_Subpages/Biology1.asp> Accessed October 6, 2011..

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Designating the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment; Removing the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment of Gray Wolf From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, February 8, 2006 (71 FR 6634-6660).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data cited by Brad Knickerbocker, Gray wolves may lose US protected status, Christian Science Monitor, Febraury 1, 2007.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Reissuance of Final Rule To Identify the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment and To Revise the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 76 Fed. Reg. 26086.

Gray wolf (Southwest DPS) (Canis lupus (Southwest DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/28/1976 | Recovery plan: 9/15/1982 |

Range: AZ(b), NM(b) --- CO(x), OK(x), TX(x), UT(x)

SUMMARY

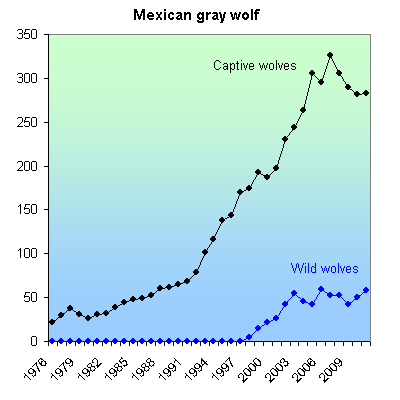

Hunting and trapping resulted in the extirpation of Mexican gray wolves from the United States by 1970. Wolves captured in Mexico were used to establish a captive-breeding program and as of 2010, there were about 50 Mexican gray wolves in the wild.

RECOVERY TREND

The southwestern gray wolf's (Canis lupus) range includes the entire range of the Mexican gray wolf (C. l. baileyi; southern New Mexico, southern Arizona, western Texas and northern Mexico) as well as northern Arizona, northern New Mexico, southern Utah and southern Colorado -- areas historically occupied by other gray wolf subspecies [1]. The wolf was purposefully hunted to near extinction in the Southwest in order to eliminate livestock depredation. In 1970, the last Mexican gray wolf was shot in Texas and the subspecies was extirpated from the United States. At that time, no wolves were present in what is now delineated as the range of the southwestern population.

The Mexican gray wolf was placed on the endangered species list in 1976 and the last five wild wolves from Mexico were captured and moved to captive breeding facilities in the United States and Mexico between 1977 and 1980 [2]. A federal recovery plan was developed in 1982 [3]. By the late 1980s captive breeding facilities were successfully rearing Mexican gray wolves, but none had been reintroduced to the wild. Conservationists filed suit in 1990, obtaining a settlement requiring reintroduction [4]. On March 29, 1998 the first 11 captive Mexican gray wolves were released into the Blue Range of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona near the New Mexico border. By Dec. 31, 2005, there were 35 to49 wild wolves in eight packs on the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest and White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona, and in the adjacent Gila National Forest in New Mexico [5]. The total population of wild and captive wolves grew from 22 in 1976 to 309 in 2004 [6, 7]. In 2010, the total number of captive and wild wolves was 333 [8,9]. Captive breeding is actively curtailed because of constraints on pen space and the failure of FWS to continue efforts to release new wolves into the wild [9].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Final Rule To Reclassify and Remove the Gray Wolf From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife in Portions of the Conterminous United States; Establishment of Two Special Regulations for Threatened Gray Wolves. April 1, 2003 (68 FR 15804).

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1998. Establishment of a Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Gray Wolf in Arizona and New Mexico. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. January 12, 1998 (63 FR 1752).

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, NM.

[4] Wolf Action Group v. Lujan, No. 90-0390 HB (DNM filed Apr. 3, 1990) [5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Gray Wolf Populations in the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Midwest Region. Accessed 1/18/06.

[6] Siminski, P. 2005. Census Report as of 31/12/2004. Email from Peter Siminski, Director of Collections, Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, August 10, 2005

[7] Robinson, M. 2005. Wild Mexican gray wolves in the U.S. and Mexico, 1920-2005. Email from Michael Robinson, Center for Biological Diversity, August 1, 2005.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildife Service. 2011. Mexican Wolf Blue Range Reintroduction Project Statistics. www.fws.gov/southwest/es/mexicanwolf/pdf/MW_popestimate.pdf

[9] Michael Robinson. 2011. Personal Communication, Captive Mexican Wolves in the United States.

Gray wolf (Western Great Lakes DPS) (Canis lupus (Western Great Lakes DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 3/9/1978 | Listed: 1/4/1974 | Recovery plan: 1/31/1992 |

Range: MN(b), WI (b), MI(b), IA (o), IL (o), IN (o), ND (o), OH (o), SD (o)

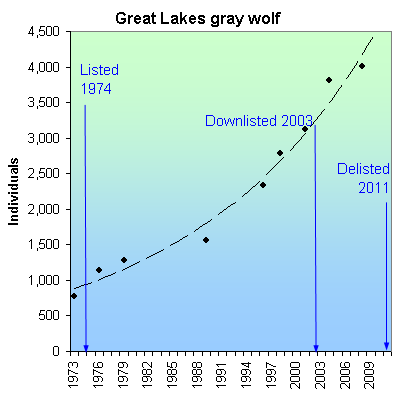

SUMMARY

Hunting and persecution drove the gray wolf to near extinction, with only a small number of wolves remaining in Minnesota and Michigan when the species was listed in 1974. The total Great Lakes wolf population increased from fewer than 1,000 at the time of listing to approximately 4,013 in 2008.

RECOVERY TREND

The Western Great Lakes population of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) occurs in Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, where it was hunted and targeted by predator eradication programs through the early 20th century [2]. Bounty programs initiated in the 19th century continued through as late as 1965 [2]. As a result, the gray wolf was driven to near extinction. In 1974, when the gray wolf became one of the first species protected under the 1973 Endangered Species Act, it was found in the wild only in extreme northeastern Minnesota where several hundred wolves remained, and on Isle Royale [2].

Minnesota: Just prior to listing, gray wolf numbers in Minnesota were estimated at between 500 and 1,000 individuals [4]. By 1978, numbers appeared to have increased slightly and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed downlisting the Minnesota gray wolf to “threatened” so that “problem” wolves could be killed [5]. A 1988-89 winter survey produced an estimate of 1,500 to 1,750 wolves and in 1998, surveys estimated that there were more than 2,400 individual wolves in Minnesota [4]. As of late winter 2004-05, there were roughly 3,020 gray wolves (485 packs) in Minnesota [6]. In addition, over the last three decades, wolves have increased their range in the north-central and central parts of Minnesota [4].

Wisconsin: From 1960 to 1975, there were no breeding wolves in Wisconsin [4]. As populations in Minnesota expanded after listing however, wolves apparently dispersed into the state. In 1980, 25 wolves inhabited Wisconsin; by 1995 the number had increased to 83 wolves comprising 18 packs, and by 2004 there were 373 wolves comprising 109 packs [4]. As of early 2005, there were about 425 gray wolves in Wisconsin [6].

Michigan: In 1995, 80 wolves were counted in Michigan, up from a small number of individuals found on Isle Royale and none on the mainland at the time of listing [4]. By 2000, this number had increased to 216 [4], and as of late winter 2004-05, there were roughly 435 gray wolves in the state: 405 (87 packs) on the Upper Peninsula and 30 (3 packs) on the Isle Royale [6].

The Western Great Lakes wolf was downlisted to "threatened" status in 2003 and removed from the endangered species list in 2011 [8].

CITATIONS

1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Oregon District Court Rules Against Gray Wolf Reclassification. Website <http://www.fws.gov/midwest/wolf/esa-status/or-court-rule.htm> accessed 3/2006.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Gray Wolf (Canis lupis) Biologue, updated May, 2004. Available at <http://www.fws.gov/midwest/wolf/biology/biologue.htm>.

[3] International Wolf Center. 2005. Gray Wolf Population Trends in the Contiguous United States. Updated September, 2005. (www.wolf.org)

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Gray Wolf Recovery in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. Available at <http://www.fws.gov/midwest/wolf/recovery/r3wolfct.htm>.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1978. Reclassification of the Gray Wolf in the United States and Mexico, with Determination of Critical Habitat in Michigan and Minnesota. Federal Register (43:9607-9615).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Questions and Answers about gray wolf recovery in North America. Website <http://www.fws.gov/midwest/wolf/recovery/namerica.htm> accessed 3/2006.

[7] International Wolf Center. 2011. Gray Wolf Population Trends in the Contiguous United States. Website http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/wow/regions/United_States_Subpages/Biology1.asp> Accessed October 6, 2011.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Revising the Listing of the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) in the Western Great Lakes. 76 Fed. Reg. 81666.

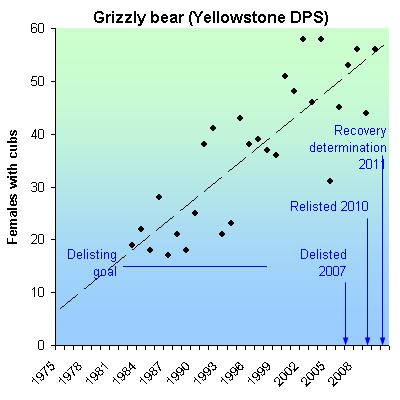

Grizzly bear (Yellowstone DPS) (Ursus arctos (Yellowstone DPS))

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 7/28/1975 | Recovery plan: 3/13/2007 |

Range: MT(b), WY(b)

SUMMARY

Grizzly bears were extirpated from most of the Lower 48 states by killing, habitat destruction, food chain disruption, and the loss of large wildland areas. By 1975, only six populations remained. Due to Endangered Species Act protections, the Yellowstone grizzly bear population increased from ~224 bears in 1975 to ~582 in 2010. It was delisted in 2007, relisted in 2010 due to concerns about habitat loss and global warming, and declared recovered in 2011 by a federal status report.

RECOVERY TREND

The grizzly bear (Ursus horribilis) formerly ranged over much of North America from the mid-plains westward to California and from central Mexico north to Canada and Alaska [1]. During the early 1880s there were approximately 50,000 grizzlies in the lower 48 states [1]. Between 1850 and 1920, the species was extirpated from 95 percent of its continental U.S. range [2]. In 1922, 37 populations remained [3], declining to six by 1975 when the grizzly bear was listed as “threatened” under the federal Endangered Species Act in the conterminous U.S. [3]. At the time of listing, fewer than 1,000 grizzlies remained in about 2 percent of the species' historic range [1].

Early declines in grizzly populations were largely a result of persecution by European settlers; grizzly bears were shot, poisoned, and trapped wherever they were found [11]. Despite protection under the Endangered Species Act, human-caused mortality, largely resulting from human bear conflicts, has remained the biggest threat to grizzlies [1]. Approximately 88 percent of U.S. grizzly bear deaths documented during studies over the past 20 years were caused by humans, both legally and illegally [2]. Habitat degradation associated with rural or recreational development, road building, and energy and mineral exploration is also a major threat to grizzly bear survival [5]. Habitat destruction in valley bottoms and riparian areas is particularly harmful [5].

The 2005 population was between 1,200 and 1,400 grizzly bears in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and Washington state [1, 3]. Grizzly bears have also been reported in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado in recent years, but have not been confirmed since a grizzly was killed in 1979 [3]. Only two populations (Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide) contain more than 350 individuals [6]. There are six grizzly bear recovery areas in the conterminous U.S. including Yellowstone National Park and surrounding areas.