American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 8/13/1989 | Recovery plan: 9/27/1991 |

Range: AR(b), KS(b), MA(b), NE(b), OH(b), OK(b), RI(b), SD(b), TX(b) --- AL(x), CT(x), DE(x), DC(x), FL(x), GA(x), IL(x), IN(x), IA(x), KY(x), LA(x), ME(x), MD(x), MI(x), MN(x), MS(x), MO(x), MT(x), NH(x), NY(x), NJ(x), NC(x), ND(x), PA(x), SC(x), TN(x), VT(x), VA(x), WV(x), WI(x)

SUMMARY

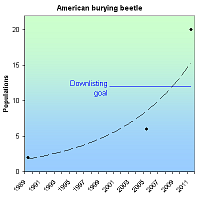

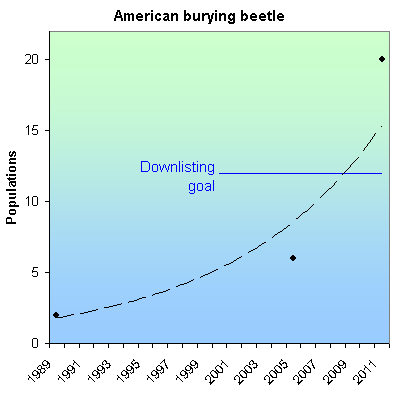

The cause of the American burying beetle's 90% range loss is not well understood, but is thought to be due to disruptions in the food and reproductive web. It is threatened by competition, drought, invasive ants and habatat loss. When listed as endangered in 1989, there were only two known populations. Captive breeding, reintroduction efforts and intensive surveys have increased the total number of populations to 20 or more in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) is a large, spectacularly colored orange and black insect. It formerly occurred across a vast range from Nova Scotia south to Florida, west to Texas, and north to South Dakota. It was documented in 150 counties in 34 states, the District of Columbia, and three Canadian provinces. Total historical numbers are not known, but the species may well have occurred in the tens of millions. The burying beetle's dramatic decline has been called "difficult to imagine" and “one of the most disastrous declines of an insect’s range ever to be recorded” [2]. It was extirpated from mainland New England through New Jersey by the 1920s, from the entire mainland east of the Appalachian Mountains by the 1940s, and from the mainland east of the Mississippi River by 1974. It is absent from about 90 percent of its historic range.

The largest of North America's 32 burying beetles, N. americanus is uniquely dependent upon quail-size carrion weighing 100 to 200 grams [1, 15]. Males smell freshly dead mammals and birds (and occasionally even fish) within an hour of death and up to two miles away. Females arrive shortly thereafter, attracted by male pheromones. A competition ensues and is typically won by the largest male and female. Lying on their backs, the winning couple inches the carrion into an excavated burial chamber. During this time, orange phoretic mites borne by the beetles leap to the carcass, cleaning it of fly eggs and microbes. The buried carcass is relieved of its feathers, feet, tail, ears and/or fur. Now known as a "brood ball," it is coated with oral and anal embalming secretions to retard fungal and bacterial growth. The beetles then mate and within 24 hours lay eggs in the soil near the carcass. White grubs emerge three or four days later and are carried to the carcass. The parents also defend the grubs from predators and feed them regurgitated food. The American burying beetle is one of the few non-colonial insects in the world to practice dual parenting. In approximately a week, the grubs leave the chamber and pupate into adults.

The cause of the American burying beetle's decline is not well understood, but the most cogent hypotheses see it as victim of interacting food chain disturbances which reduced the number of large carcasses [2]. The passenger pigeon, which formerly occurred in the billions, was an ideal size. It was last seen in 1914 and was greatly reduced in number in the decades preceding. Its decline and disappearance occurred just prior to the burying beetle's. Other endangered or greatly reduced carrion of ideal size include the black-footed ferret, northern bobwhite, and greater prairie chicken. Competition for dwindling carrion numbers was exacerbated by increasing numbers of mid-sized predators following the extinction or decline of large predators such as the eastern cougar, mountain lion and gray wolf. In their absence, coyotes, raccoons, fox and other mid-size scavengers increased in number and consumed more quail-size carrion. Finally, as habitats became more fragmented mid-size predators were increasingly able to exploit forest and grassland edges, taking more carrion.

At the time of listing in 1989, two populations were known: one on Block Island, Rhode Island and one in eastern Oklahoma [1]. Since then, populations have been discovered in South Dakota (1995), Nebraska (1992), Kansas (1997), Arkansas (1992) and Texas (2003), as well as additional populations in Oklahoma [3, 23]. The total number of populations has increased to at least 20 as of 2011 [7, 11, 13, 10, 22, 23].

RHODE ISLAND. Located 12 miles off the south coast of Rhode Island, Block Island supports the last natural population of the American burying beetle east of the Mississippi River. The island is free of foxes, raccoons, skunks and coyotes. A study of one-third of the population determined that it was relatively stable between 1991 and 1997 (mean=184), steadily grew to 777 in 2006, and then declined to 80 in 2011 in part because of a reduction in supplementation of carcasses [8]. This population served as the source for the successful Roger Williams Park Zoo captive breeding program initiated in 1994 and for direct translocations to Nantucket and Penikese Island.

MASSACHUSETTS. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Massachusetts shortly after 1940 [1] and was reintroduced to the 70-acre Penikese Island in Buzzards Bay over a four-year period between 1990 and 1993. Reintroduced beetles initially came from a Boston University captive breeding population originating from Block Island stock [6]. The population persisted at low numbers through 2002, but was not located in 2003, 2004 or 2005. On Nantucket, 2,892 beetles were introduced from the Roger Williams Park Zoo between 1994 and 2005 to the Audubon Society’s Sesachacha Heathland Wildlife Sanctuary (east side of the island) and the Nantucket Conservation Foundation’s Sanford Farm (west side of the island) [5, 6, 21]. Existing and new beetles were trapped and provisioned with quail carcasses each summer to boost larva production [5]. The introduction program ended in 2005 in order to determine if population is self-sustaining [6]. The Penikese Island reintroduction effort has been deemed a failure, and the success of the Nantucket effort is unknown, although the population is believed to persist [23].

OHIO. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Ohio shortly after 1974 when it was last seen near Old Man's Cave in Hocking Hills State Park [9, 10]. A short-lived captive population derived from Block Island stock was established in 1991 at the Insectarium of the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden [1]. In July 1998, Ohio became the site of the first mainland introduction when 35 pairs of beetles taken from a wild population near Fort Chaffee, Ark. were introduced to the Waterloo Wildlife Experiment Station in southeast Ohio [10]. The Waterloo population was augmented in 1999 (20 pairs and 15 females) and 2000 (33 pairs and four males), but not 2001 or 2002. Additional augmentation occurred in 2003. A captive population established at Ohio State University in 2002 produced 828 beetles as of 2004; 199 of these were used for reintroductions in 2003 and 156 were reintroduced in 2004. The Wilds (managed by the Columbus Zoo) plans to create a second captive colony [10] and a second reintroduction is planned for the Athens District of the Wayne National Forest [11]. The success of the Ohio reintroduction efforts is unknown but is thought to be limited [23].

MISSOURI. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Missouri in the early 1980s [1]. It has not been relocated despite repeated and recent surveys [12]. A captive breeding population was established at the Monsanto Insectarium, St. Louis Zoo in 2004 (with 10 pairs from Ohio State University) and 2005 (with wild beetles from Arkansas) [7, 15]. Six-hundred-fifty-four adults were produced as of June 2005, 50 of which were transferred to Ohio State University. Plans are being developed to introduce the species to The Nature Conservancy and Missouri Department of Conservation lands. [7].

OKLAHOMA. The presence of American burying beetles has recently been confirmed in 22 eastern Oklahoma counties, reported but unconfirmed in two more, and likely to occur in nine more [16]. The largest known concentrations are a population at Camp Gruber and a smaller one on private timber lands held by Weyerhaeuser International. Captures (not to be confused with population estimates) at Camp Gruber fluctuated around a mean of 213 adults between 1992 and 2003 without discernable trend. Captures at Weyerhaeuser had a mean of 52 adults between 1997 and 2003, but this population collapsed in 2006 and 2007, perhaps due to drought or fire ants [23].

NEBRASKA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Nebraska in 1992 [18]. Between 1995 and 1997, nearly 1,000 individuals were trapped or collected in the upland grasslands and cedar tree savannas of the dissected loess hills south of the Platte River in Dawson, Gosper and Lincoln counties of Nebraska. The population is estimated at about 3,000 adults.

SOUTH DAKOTA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in South Dakota in 1995 and is believed to have a statewide population in excess of 500 adults [17].

ARKANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Arkansas in 1992 [3]

KANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Kansas in 1997 [19].

TEXAS: The American burying beetle, thought to be extirpated from Texas since the 1930s, was rediscovered in 2003 [3]. Two populations are now known to exist, one on a military base, the other on a Nature Conservancy preserve.

The American burying beetle recovery plan states: "The interim objective [extinction avoidance] will be met when the extant eastern and western populations are sufficiently protected and maintained, and when at least two additional self-sustaining populations of 500 or more beetles are established, one in the eastern and one in the western part of the historical range. Reclassification will be considered when (a) 3 populations have been established (or discovered) within each of four geographical areas (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and the Great Lake states), (b) each population contains 500+ adults, (c) each population is self-sustaining for five consecutive years, and, ideally, each primary population contains several satellite populations.”

The beetle remains threatened by the limited availability of carcasses to use for reproduction, by invasive species such as fire ants which compete for carcasses, and by drought and climate change. The Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport tar sands oil from Canada to Texas, is a new threat to the beetle in 2011 and would cut through the core of the beetle's range in South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

CITATION

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) recovery plan. Newton Corner, MA.

[2] Sikes, D.S. 2002. A review of hypotheses of decline of the endangered American burying beetle (Silphidae: Nicrophorus americanus Olivier). Journal of Insect Conservation 6: 103–113

[3] Quinn, M. 2006. American Burying Beetle (ABB). Website (http://www.texasento.net/ABB.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[4] Peyton, M.M. 1997. Notes on the range and population size of the American Burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) in the dissected hills south of the Platte River in central Nebraska. Paper presented at the 1997 Platte River Basin Ecosystem Symposium, Feb. 18-19, 1997 Kearney Holiday Inn Kearney, Nebraska.

[5] Mckenna-Foster, A.A., M.L. Prospero, L. Perrotti, M. Amaral, W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction to Nantucket, MA, 2004-2005. Abstract presented at the First Nantucket Biodiversity Initiative Conference, September 24, 2005, Coffin School, Egan Institute of Marine Studies, Nantucket, MA.

[6] Amaral, M. 2005. Personal communication with Michael Amaral, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Concord, NH, November 28, 2005.

[7] Homer, P. 2005. Missouri's Threatened and Endangered Species Accomplishment Report: July 1, 2004 - June 30, 2005. Missouri Department of Conservation.

[8] Raithel, C. 2012. American burying beetle, Southwest Block Island trend, 1991-2011. Spreadsheet provided by Christopher Raithel, Rhode Island Dept of Environmental Management, Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, April 5, 2012.

[9] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2005. American Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus americanus. Website (www.dnr.state.oh.us/wildlife/Resources/projects/beetle/beetle.htm) accessed January 28, 2006.

[10] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2004-2005 Wildlife Population Status and Hunting Forecast.

[11] Wayne National Forest. 2004. Schedule of Proposed Action, 10-01/04-12/31/04.

[12] Stevens, J. and B. Merz. American Burying Beetle Survey in Missouri. St. Louis Zoo, Department of Invertebrate. Website (http://biology4.wustl.edu/tyson/projectszoo.html) accessed January 29, 2006.

[13] Dabeck, L. 2006. The American Burying Beetle Recovery Program: Saving nature's most efficient and fascinating recyclers. Roger Williams Park Zoo. Website (www.rogerwilliamsparkzoo.org/conservation/burying%20beetle%20program.cfm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[14] Kozol, A. J. 1990. NICROPHORUS AMERICANUS 1989 laboratory population at Boston University: a report prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Unpublished report.

[15] Stevens, J. 2005. Conservation of the American burying beetle. CommuniQue, September, 2005:9-10.

[16] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Website (www.fws.gov/ifw2es/Oklahoma/beetle1.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[17] South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. 2006. The American Burying Beetle in South Dakota. Website (www.sdgfp.info/Wildlife/Diversity/ABB/abb.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[18] Peyton, M.M. 2003. Range and population size of the American burying beetle (Coleoptera:Silphidae) in the Dissected Hills of South-central Nebraska. Great Plains Research 13(1): 127-138

[19] Miller, E.J. and L. McDonald. 1997. Rediscovery of Nicrophorus americanus Olivier (Coleoptera Silphidae) in Kansas. The Coleopterists' Bulletin 5(1):22.

[20] Mckenna-Foster, A., W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction on Nantucket 2005. Unpublished report.

[21] Perrotti, L. 2006. Roger Williams Park Zoo American Burying Beetle Project Statistics. Spreadsheet provided by Lou Perrotti, American Burying Beetle project coordinator, Roger Williams Park Zoo, Providence, RI, February, 2006.

[22] NatureServe. 2011. American Burying Beetle Species Profile. Available at: http://www.natureserve.org

[23] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. American Burying Beetle (Nicropherus americanus) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation. 53 pp.

American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 8/11/1977 |

| Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(b), AR(m), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(m), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(m), KY(b), LA(m), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(m), MO(m), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(m), OH(b), OK(m), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(m), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

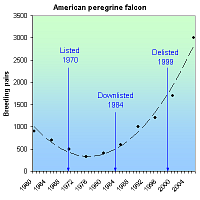

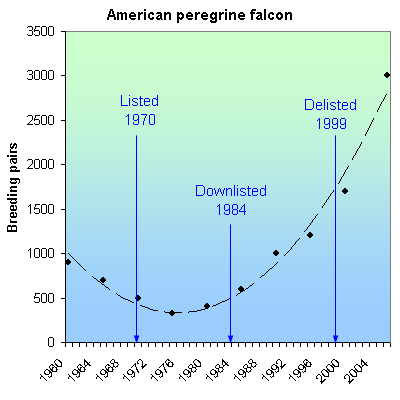

The use of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides thinned American peregrine falcon eggshells, causing reproductive failure and population declines. The banning of DDT, captive-breeding efforts and nest protections allowed falcons to increase from 324 breeding pairs in 1975 to 3,005 pairs as of 2006. The species was delisted in 1999.

RECOVERY TREND

The American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) breeds only in North and Central America and occurs throughout much of North America from the subarctic boreal forests of Alaska and Canada south to Mexico [1]. It is estimated that prior to the 1940s, there were approximately 3,875 nesting pairs of peregrines in North America [1]. From the 1940s through the 1960s, however, the population of the peregrine, and many other raptors, crashed as a result of the introduction of synthetic organochlorine pesticides to the environment. By 1975, there were only 324 known nesting pairs of American peregrine falcons in the U.S. [2].

Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [1]. Organochlorine pesticides were put into use following World War II. Use peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s and continued through the early 1970s [1]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey because they ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches [1]. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. During the period of DDT use in North America, eggshell thinning and nesting failures were widespread in peregrine falcons, and in some areas, successful reproduction virtually ceased [1].

The degree of exposure to these pesticides varied among regions, and peregrine falcon numbers in more contaminated areas suffered greater declines [1]. The eastern population plunged from an estimated 350 active nest sites in the 1930s and 1940s to no active breeding birds from 1964 to 1975 [3]. Peregrine falcons in the Great Plains states east of the Rocky Mountains and south of U.S. and Canadian boreal forests were also essentially extirpated [1]. West of the 100th meridian, peregrine falcons were significantly reduced [1]. Local populations were greatly depressed or extirpated and by 1965 fewer than 20 pairs were known west of the U.S. Great Plains [1].

In 1970, the American peregrine was listed as endangered and efforts to recover the species began. The use of DDT was banned in Canada in 1970 and in the United States in 1972 [1]. This was the single-most significant action in the recovery of the peregrine falcon [1]. In addition, in the eastern United States, efforts were made to reestablish peregrine falcons by releasing offspring from a variety of wild stocks that were held in captivity by falconers [1]. The first experimental releases of captive-produced young occurred in 1974 and 1975 in the eastern United States [1]. These and future releases demonstrated that “hacking,” the practice of retaining and feeding young captive bred birds in partial captivity until they are able to fend for themselves, was an effective method of introducing captive-bred peregrines to the wild [1]. Since then, more than 6,000 falcons have been released in North America [1]. Approximately 3,400 peregrines were released in parts of southwest Canada, the northern Rocky Mountain States, and the Pacific Coast states [1].

In the late 1970s, Alaska became the first place American peregrine falcon population growth was documented and, by 1980, populations began to grow in other areas [1]. Not only did the number of peregrine falcons begin to increase, productivity (another important measure of population health) improved [1]. Efforts to reestablish peregrine falcons in the East and Midwest proved largely successful, leading to downlisting of the species in 1984 [1], and by 1999 peregrines were found to be nesting in all states within their historical range east of the 100th meridian, except for Rhode Island, West Virginia and Arkansas [1]. In highly urban areas, peregrine falcons showed great adaptability, and began substituting skyscrapers for natural cliff faces as nesting sites [4]. By 1998, the total known breeding population of peregrine falcons was 1,650 pairs in the United States and Canada, far exceeding the recovery goal of 456 pairs. Other recovery goals, including estimates of productivity, egg-shell thickness, and contaminants levels, had also been met, allowing the species to be delisted in 1999 [1]. Monitoring of American peregrine populations has continued under a post-delisitng monitoring plan [5]. The estimated North American population was 3,005 pairs as of 2006 [6].

ALASKA: Surveys conducted between 1966 and 1998 along the upper Yukon River demonstrated increases in the number of occupied nesting territories from a low of 11 known pairs in 1973 to 46 pairs in 1998 [1]. Similarly, along the upper Tanana River, the number of occupied nesting territories increased from two in 1975 to 33 in 1998 [1]. The recovery objective of 28 occupied nesting territories in the two study areas was first achieved in 1988, with 23 nesting territories on the Yukon River and 12 on the Tanana River [1].

PACIFIC STATES: By 1976, no American peregrine falcons were found at 14 historical nest sites in Washington [1]. Oregon had also lost most of its peregrine falcons and only one or two pairs remained on the California coast [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 to 1998 indicated a steadily increasing number of American peregrine falcon pairs breeding in Washington, Oregon and Nevada [1]. Known pairs in Washington increased from 17 to 45 and in Oregon from 23 to 51 [1]. The number of American peregrine falcons in California increased from an estimated low of five to 10 breeding pairs in the early 1970s to a minimum of 167 occupied sites in 1998 [1]. The increase in California was concurrent with the restriction of DDT and included the release of more than 750 American peregrine falcons through 1997 [1].

ROCKY MOUNTAINS/SOUTHWEST: The Rocky Mountain/Southwest population of the American peregrine falcon has made a profound comeback since the late 1970s when surveys showed no occupied nest sites in Idaho, Montana or Wyoming and only a few pairs in Colorado, New Mexico and the Colorado Plateau, including parts of southern Utah and Arizona [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 through 1998 indicated that the number of American peregrine falcon pairs in the Rocky Mountain/Southwest area has steadily increased [1]. In 1991, there were 367 known pairs; in 1998 the number of pairs increased to 535 [1].

EASTERN STATES: The eastern peregrine population has a unique history and complex status under the Act [1]. Peregrine falcons were extirpated in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada by the mid-1960s [1]. Releases of young captive bred peregrines have reestablished populations throughout much of their former range in the East [1]. In 1998, 193 pairs were counted in five designated eastern state recovery units [1]. The number of territorial pairs recorded in the eastern peregrine falcon recovery area increased an average of 10 percent annually between 1992 and 1998 [1]. Equally important, the productivity of these pairs during the same seven-year period averaged 1.5 young per pair, demonstrating sustained successful nesting [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Final Rule to Remove the American Peregrine Falcon from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, and to Remove the Similarity of Appearance Provision for Free-Flying Peregrines in the Conterminous United States. Federal Register (64 FR 46542).

[2] Hoffman, C. 1999. The Peregrine Falcon is Back! New release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 20, 1999.

[3] Clark, K. 2005. The Peregrine Falcon in New Jersey, Report for 2005. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program.

[4] New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. Fact sheet, Peregrine Falcon Falco pereginus. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program. Website <http://www.njfishandwildlife.com/tandespp.htm> accessed February, 2006.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Monitoring Plan for the American Peregrine Falcon, A Species Recovered Under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Endangered Species and Migratory Birds and State Programs. Pacific Region, Portland Oregon 53pp.

[6] Green, M., T. Swem, M. Morin, R. Mesta, M. Klee, K. Hollar, R. Hazelwood, P. Delphey, R. Currie, and M. Aramal. 2006. Monitoring Results for Breeding American Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus anatum), 2003. Biological Technical Publication BTP-R1005-2006. U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(m), AR(m), CA(m), CO(m), CT(m), DE(m), DC(m), FL(m), GA(m), ID(m), IL(m), IN(m), IA(m), KS(m), KY(m), LA(m), ME(m), MD(m), MA(m), MI(m), MN(m), MS(m), MO(m), MT(m), NE(m), NV(m), NH(m), NY(m), NM(m), NJ(m), NC(m), ND(m), OH(m), OK(m), OR(m), PA(m), RI(m), SC(m), SD(m), TN(m), TX(m), UT(m), VT(m), VA(m), WA(m), WV(m), WI(m), WY(m) ---

SUMMARY

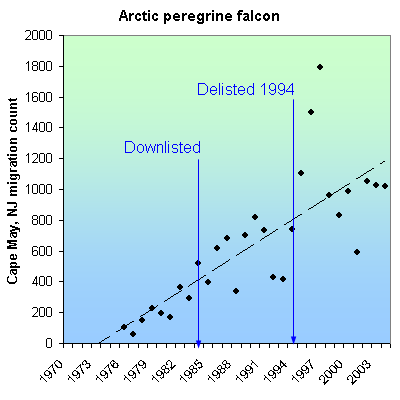

The Arctic peregrine falcon declined due to the egg shell-thinning effects of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides. Its listing as an endangered species in 1970 (along with other birds of prey) prompted the EPA to ban DDT in 1972. Counts of migratory Arctic falcons increased from 103 in 1976, to 1,017 in 2004. The species was downlisted to threatened in 1984 and delisted in 1991.

RECOVERY TREND

The Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius) is one of three peregrine falcon subspecies [1]. It nests in tundra regions of Alaska, Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Quebec, and possibly Labrador), and the ice-free perimeter of Greenland [1]. It is a long-distance migrant that winters in Latin America from Cuba and Mexico south through Central and South America [1].

Severe declines in peregrine falcon numbers began in the 1950s [1]. These declines were linked to organochlorine pesticides that were put into use following World War II, and whose use peaked in the late 1950s-early 1960s [1]. Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [2]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey which, being at the top of the food chain, ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. Arctic peregrine numbers reached their lowest levels in the early 1970s and in some areas of North America successful reproduction virtually ceased [1]. Populations are thought to have decreased by as much as 80 percent [2].

The listing of the Arctic peregrine falcon as endangered in 1970--as well as the bald eagle, brown pelican, and American peregrine falcon shortly before--fostered a national outcry against the production and spaying of DDT. In 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency banned most used of DDT in the United States [1]. Canada had already restricted DDT use in 1970. These restrictions are the central cause of the recovery of the Arctic and American peregrine falcons (the bald eagle and brown pelican benefited greatly as well, but their recovery also involved substantial habitat protections and reintroductions).

As DDT levels declined after 1972, peregrine falcon productivity rates rose to pre-DDT levels and the population size and range began to increase. This happened most rapidly in northern areas, where pesticide exposur was lower and impacts upon populations were less severe [1]. In 1984, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service downlisted the Arctic peregrine falcon from endangered to threatened status [2, 6]. In 1991, the agency initiated a review determine if the species had recovered [2] and in 1994 removed it from the endangered species list [6].

Four major factors were considered in the delisting process: (1) Population size and trend, (2) reproductive performance, (3) pesticide residues in eggs, and (4) eggshell thickness [1]. Despite a lack of long-term studies using consistent methodologies, there was strong evidence of significant population increases throughout the Arctic [1]. Four areas in northern North America (one in Alaska and three in Canada’s North West Territories) for which historical survey information was available indicated the number of Arctic peregrine pairs occupying nesting territories increased since the 1960s [1]. Some areas of Alaska even exceeded the original estimates of pre-DDT-era population size [1]. In addition, in the eastern Arctic, peregrines began nesting in previously vacant nesting sites [1]. Standardized yearly migration counts at New Jersey’s Cape May, an area where Arctic peregrines concentrate during migration, also saw increasing numbers, most likely from Arctic breeding grounds especially in Greenland and eastern Canada (these counts may have also contained peregrines in the American subspecies; however, banding recoveries indicate that the majority of peregrines along the East Coast during fall migration are from the Arctic and thus represent a true increase in Arctic peregrine numbers) [1].

Productivity in all regions where data had been gathered was sufficient to support a stable or increasing population since the 1980s [1]. There had also been improvements in levels of DDE concentration in eggs. Concentrations in excess of 15-20 parts per million (wet weight basis) are associated with high rates of nesting failure. Residue in eggs in 1993 was well below this critical level [1]. Alaskan eggshells collected between 1988 to 1991 were on average only 12 percent thinner than pre-DDT thickness (17 percent or greater reduction in thickness results in population declines).

Arctic peregrine falcon numbers have continued to rise after the species' delisting. On the Sagavanirktok River in Alaska, where Arctic peregrine surveys have been conducted since the late 1950s, the number of pairs increased from five in 1958, to 23 in 1992, to 25 in 1999 [3]. Migration counts at the Cape May Hawkwatch site in New Jersey increased from 103 in 1976 to 1,024 in 2003 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Proposal to Remove the Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 58 Fed. Reg 188.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Peregrine falcon, (Falco peregrinus anatum, Falco peregrinus tundrius, Falco peregrinus pealei). Species account. Website <http://www.fws.gov/species/species_accounts/bio_pere.html> accessed October, 2005.

[3] Wright, J.M. and P.J. Bente. 1999. Documentation of active peregrine falcon nest sites, 1 Oct 1994- 31 March 1998. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Annual research report. Endangered species conservation fund federal aid project SE-2-9, 10, and 11. Juneau, AK. 15 pp.

[4] Cape May Bird Observatory. 2012. Cape May Hawkwatch, Cape May, New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society. Website <http://www.njaudubon.org/Sightings/cmhw25.html> accessed April 2, 2012.

[5] NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Removal of Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 50796.

Atlantic green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas mydas)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(s), DE(m), FL(b), GA(b), LA(s), MA(s), MS(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), TX(s), VI(b), VA(m) ---

SUMMARY

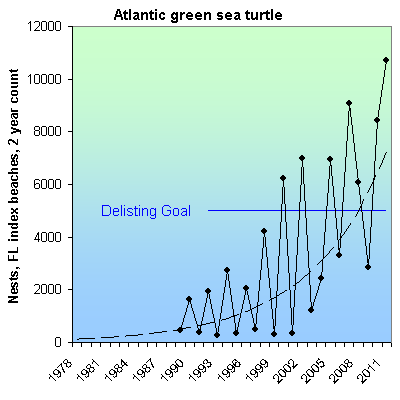

The Atlantic green sea is threatened by egg collection, hunting, vandalism, disturbance while nesting, beach development, habitat loss, and sea level rise. Its population has increased in the United States since being listed as endangered in 1978, but systematic surveys only began in 1989. It grew by 2,206% in Florida between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) and has achieved its population size recovery goal.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 2]. It migrates enormous distances between foraging and nesting areas [2]. When not migrating, the green sea turtle’s typical near-shore habitat includes shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets [1]. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches [3]. Females generally breed every two or more years, and nest an average of three to four times per breeding year [4].

Exploitation of the green sea turtle, its eggs and its habitat resulted in population declines [1]. Although green sea turtle populations continue to decline throughout much of their range due to directed harvest (both illegal and legal), incidental capture in near-shore gillnets, and negative impacts on essential habitats [1], two populations that nest in the United States (Florida and Hawaii) have increased in size since the species was placed on the endangered list in 1978 [3].

Green sea turtle populations in the U.S. Atlantic occur from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean [1, 2]. In the U.S. Pacific, green sea turtles occur from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 2]. Atlantic green sea turtles are variously considered a population and a subspecies (Chelonia mydas mydas) [1]. In the U.S. Atlantic, nesting occurs primarily on beaches along Florida’s east coast, although smaller numbers of nests can be found in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico [5]. Foraging occurs in the Gulf of Mexico to Texas and along the Atlantic Coast to Massachusetts [1].

CARIBBEAN

Reliable, long-term nesting data are unavailable for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands [8]. The number of green turtle nests has remained low for all the islands, but there appears to have been a gradual increase in the numbers of juveniles observed in foraging grounds since the mid-1970s [8]. The largest concentration of nests occurs on St. Croix, where an average of 100 were counted per year between 1980 and 1990. Waters surrounding the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico have been designated critical habitat [1].

FLORIDA

State-wide population counts have been conducted in Florida since the 1970s, but are not strictly controlled for survey effort and area, especially in the early years. Thus while it is known that Florida's nesting green sea turtle population has increased since the 1970s, it is not possible to determine by how much. Standardized surveys on a large number of "index beaches" was initiated in 1989. They demonstrate that the number of annual green sea turtle nests increased by 2,206% between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) [4].

The number of green sea turtle nests in Florida (and in many other places), generally alternates between high and low years. Between 1989 and 2001, the number of nests in low years remained flat (250-500). Between 2003 and 2011 it grew sharply. Nesting in high years grew throughout 1989-2011, but more sharply starting in 1998.

An unusually low count in 2004 was caused by a hurricane. The biennial cycle was broken in 2009 and 2011, resulting in the highest recorded count in what should have been a low year (2011 = 10,701). It is possible to predict at this point if 2012 will be a high or low year.

NORTHERN STATES

Each winter green, Kemps Ridley and loggerhead sea turtles migrating southward from northeastern waters are regularly stranded on shores of Cape Cod Bay between Brewster and Truro [7]. These turtles die of hypothermia if not rescued. The total number of strandings ranged between 49 and 281 turtles between 1995 and 2003. Green sea turtle strandings ranged from zero to seven each year [7]. A volunteer program has been established to rescue, rehabilitate and release the turtles in Florida.

In 2005, the first verified green sea turtle nest was found in Virginia. A few females previously had laid eggs on beaches as far north as North Carolina's Outer Banks [10].

RECOVERY PLAN

In order for the green sea turtle to be delisted, the 1991 federal recovery plan requires that Florida supports an average of 5,000 nests over six consecutive years [1]. This criterion was met in 2009, 2010, and 2011 on the index beaches. As these are a subset of all nesting beaches, the delisting criteria was met in at least all years between 2007 and 2011.

The recovery plan also requires that 2) at least 105 kilometers of nesting beach be in public ownership and support at least 50 percent of U.S. nests, and 3) a reduction in stage-class mortality results in an increase in individuals in foraging grounds [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. Washington, DC.

[2] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Silver Spring, Maryland.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Office. Website (http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/Green-Sea-Turtle.htm) accessed January, 2006.

[4] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available at (http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/, accessed May, 2012).

[5] National Marine Fisheries Service. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). Threatened Species Account. Endangered Florida and Mexican Breeding Populations. NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Silver Spring, MD. Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/green.html) accessed January, 2006.

[6] Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. 2006. Florida's index nesting beach survey data. Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission,. Website (http://research.myfwc.com/features/view_article.asp?id=10690) accessed January, 2006.

[7] Lewis, D. Photo diary of a terrapin researcher. Website (http://terrapindiary.org/) accessed January 7, 2006.

[8] Hillis-Starr, Z.M., R. Boulon, M. Evans. Sea turtles in the Virgin Islands in Status and trends of the Nation's Biological Resources, USGS. Available at (http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/cr136.htm, accessed January, 2006.)

[9] Orlando Sentinel. August 6, 2005. Green Sea Turtle makes odd egg-laying visit to Virginia. Page A20.

Atlantic hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(o), DE(o), FL(b), GA(o), LA(s), MD(o), MA(o), MS(s), NY(o), NJ(o), NC(o), PR(b), RI(o), SC(o), TX(s), VI(b), VA(o) ---

SUMMARY

Globally, the number of hawksbill sea turtles may have declined by as much as 80 percent over the past century due to commerce in their shells, poaching, habitat loss, bycatch and entanglement in marine debris. Although hawksbill numbers continue to decline globally, at protected beaches on Mona Island, Puerto Rico, nests increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

Hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricatause) use different habitats at different stages of their life cycle [1]. Post-hatchling hawksbills occupy pelagic environments, taking shelter in weedlines that accumulate at convergence zones [1]. They reenter coastal waters when they reach approximately 20 to 25 centimeters carapace length [1]. Coral reefs are used as resident foraging habitat by juveniles, subadults and adults [1]. Along the eastern shores of continents where coral reefs are absent, hawksbills are known to inhabit mangrove-fringed bays and estuaries [1]. They feed primarily on sponges [1, 2]. Female hawksbills nest on low- and high-energy beaches of tropical oceans. Throughout their range, hawksbills typically nest at low densities with aggregations consisting of a few dozen, or at most a few hundred individuals [1]. Nests have been found on both insular and mainland beaches where nests are typically placed under vegetation [1]. Migratory patterns of hawksbills are not well known, although a reproductive migration is thought to take place [1, 2].

Hawksbills occur in tropical and subtropical seas of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans and nest on beaches in at least 60 different nations [3]. Along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the continental U.S., hawksbills have been reported by all of the Gulf states and from as far north as Massachusetts, although sightings north of Florida are rare [1]. Representatives of at least some life-history stages regularly occur in southern Florida (where the warm Gulf Stream current passes close to shore) and the northern Gulf of Mexico (especially Texas), in the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and along the Central American mainland south to Brazil [1].

The largest remaining concentrations of nesting hawksbills occur on the beaches of remote oceanic islands of Australia and the Indian Ocean [1]. The Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico also supports a significant population of nesting hawksbills [1]. Within U.S. jurisdiction, nesting occurs principally on beaches in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The most important nesting sites are Mona Island (Puerto Rico) and Buck Island (St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands) [1]. Within the continental United States, nesting is restricted to the southeastern coast of Florida and the Florida Keys, where one or two nests have been reported annually [1].

Quantitative data on population changes of hawksbills are scarce, in part because hawksbills were already greatly reduced in number when scientific studies of sea turtles began in the late 1950s [3]. In addition, visual evidence of hawksbill nesting is the least obvious among the sea turtle species, because hawksbills often select remote pocket beaches with little exposed sand to leave traces of revealing crawl marks [1]. An estimate of the minimum number of female hawksbills in 1989 indicated that at least 15,000 to 25,000 female hawksbills nested annually worldwide [4]. Although global numbers are very difficult to estimate, it appears that this turtle has suffered drastic decline, probably by as much as 80 percent over the last century (3). Only five regional populations, Seychelles, Mexico, Indonesia, and two in Australia, support more than 1,000 nesting females annually [3]. Hawksbill populations are either known or suspected to be declining in 38 of the 65 geopolitical units for which nesting density estimates are available [3].

CARIBBEAN

Hawksbill populations in the Western Atlantic-Caribbean region are thought to be greatly depleted [3]. In the Caribbean region, the number of females nesting annually is about 5,000 (order-of-magnitude estimate) [3]. With few exceptions, all of the countries in the Caribbean report fewer than 100 females nesting annually [3]. The largest known nesting concentrations are in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico [3]. These populations may be increasing [3]. A total of 4,522 nests were recorded in the states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo in 1996, compared to only a few hundred in the early 1980s [5].

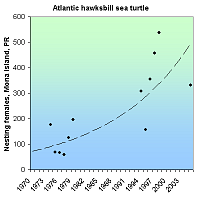

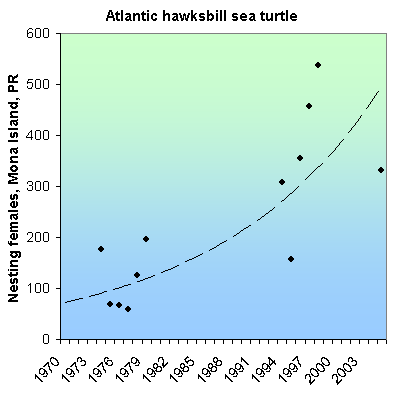

In the U.S Caribbean, there is evidence that hawksbill nesting populations have been severely reduced during the 20th century [1]. Estimates of the size of nesting populations under U.S. jurisdiction are available for only a few localities [1]. Although trends are uncertain due to long intervals between hawksbill nesting generations (hawksbill take between 30 and 40 years to reach sexual maturity) and fluctuations in the number of reproductive females that nest in a particular year [3], hawksbill numbers increased at two protected locations, Mona Island, Puerto Rico and at Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands [5]. The number of nests on Mona Island increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005 [5, 6]. On Buck Island, the number of nesting females increased from 73 in 1987 to 121 in 1998, and averaged 56 from 2001-2005 [5, 6].

International commerce in hawksbill shell (“tortoiseshell” or “bekko”) may be the most significant factor endangering hawksbill populations worldwide [1]. Despite protective legislation, international trade in tortoiseshell and subsistence use of meat and eggs continues in many countries [1]. Females and eggs are vulnerable to poaching on nesting beaches and nests are vulnerable to beach erosion [1]. Egg poaching is a serious problem in Puerto Rico and also occurs in the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The practice of beach armoring can prevent females from reaching suitable nesting sites and can result in the loss of dry nesting beaches [1, 2]. Many hawksbill nesting beaches in the Caribbean are privately owned and in jeopardy of being developed [1]. Sand mining is also a threat to nesting beaches throughout the Caribbean [1]. The extent to which hawksbills are killed or debilitated after becoming entangled in marine debris has not been quantified, but it is believed to be a serious and growing problem [1]. Incidental catch in finfish fisheries may also pose a serious threat and the ingestion of marine debris (i.e. plastic bags, styrofoam) can result in hawksbill mortality [1].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Recovery Plan for Hawksbill Turtles in the U.S. Caribbean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico. St. Petersburg, Florida.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Silver Spring, MD.

[3] Meylan, A.B. and M. Donnelly. 1999. Status Justification for Listing the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) as Critically Endangered on the 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 3(2):200–224.

[4] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.

[5] Meylan. 1999. Status of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Caribbean Region. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 3(2):177–184. Available at (http://www.iucn-mtsg.org/publications/cc&b_april1999/4.14-Meylan-Status.pdf).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/PDF/Hawksbill-Sea-Turtle.pdf

Atlantic leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea (Atlantic population))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 3/23/1979 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: CT(s), DE(s), FL(b), GA(b), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), VI(b), VA(s) ---

SUMMARY

The Atlantic leatherback sea turtles declined due to habitat destruction, commercial fishery bycatch, harvest of eggs, hunting of adults, and loss of beach nesting habitat. It is still threatened by these, and in some places by offshore oil drilling. Globally, leatherback sea turtles have been declining for decades. U.S. populations, however, have increased since being listed as endangered in 1970. Between 1989 and 2011, nests at Florida core index beaches increased from 27 to 615.

RECOVERY TREND

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), the largest living turtle species, is a monotypic genus [1]. It is typically associated with continental shelf habitats and pelagic environments. Adult leatherbacks feed primarily on jellyfish in temperate and boreal latitudes, are highly migratory and have the most extensive range of any extant reptile [1]. Although their oceanic distribution is nearly worldwide, the number of nesting sites is few [3]. Gravid females emerge onto beaches to excavate nests and lay eggs. They prefer high-energy beaches with deep, unobstructed access, which occur most often along continental shorelines [2].

In the western Atlantic, leatherbacks nest from North Carolina to southern Brazil [4]. In U.S. waters, leatherbacks can be found along the East Coast from Maine to Florida, and in the Greater and Lesser Antilles [6]. Critical habitat has been designated as the nesting beaches and adjacent waters of Sandy Point, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands [2]. The Pacific population does not nest in the United States or its territories, but has important foraging areas on the West Coast and near Hawaii [1].

Although Atlantic leatherback populations under U.S. jurisdiction have increased in size since 1970, worldwide their numbers are decreasing. Leatherback numbers have declined in Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Trinidad, Tobago and Papua New Guinea [7]. In 1980 there were more than 115,000 adult female leatherbacks worldwide. In 2005, there were less than 25,000 [6]. The most precipitous declines have occurred in the Pacific Ocean [5]. One study estimated that the number of females in the eastern Pacific decreased from 91,000 in 1980 to 1,690 in 2000 [7]. The number of leatherback nests has also declined at all major nesting beaches throughout the Pacific [6]. Nesting along the Pacific coast of Mexico, which is estimated to represent about 50 percent of all nesting, declined at an annual rate of 22 percent over the last 12 years [6].

CARIBBEAN

In the western Atlantic and Caribbean, the largest nesting assemblages are found in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Florida. Nesting data for these locations have been collected since the early 1980s [6]. Nest numbers in Florida as well as on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Culebra Island, Puerto Rico, increased over the past 20 years [8]. At St. Croix, the number of nests deposited annually on Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, the largest nesting rookery in U.S. territory, ranged from 82 in 1986 to 260 in 1991 [2]. From 1979 on, the trend indicates a 7.5 percent increase per year (SE = 0.014).

FLORIDA

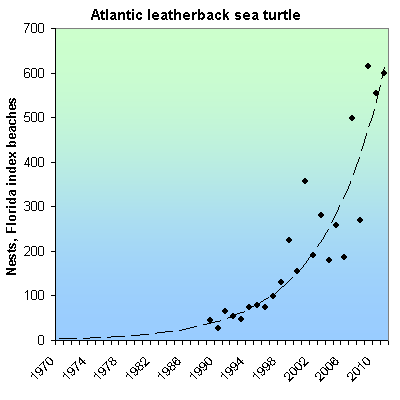

In Florida, several models estimated trends indicating a 9.1 percent increase per year (SE = 0.049) [2]. Florida has established counts on beaches used as "index beaches" where standardized counts have been conducted, allowing for more accurate comparisons between years and between beaches. From 1989 through 2011, leatherback nests at core index beaches numbered from 27 to 615 [9].

Habitat destruction, incidental catch in commercial fisheries, harvest of eggs and flesh, and offshore oil drilling continue to threaten to the survival of the Atlantic leatherback [6]. Entanglement and ingestion of marine debris, including abandoned nets, also pose a threat [1]. Artificial lights on nesting beaches can result in mortality in hatchling turtles by causing newly emerged hatchlings to become disoriented [1]. Eggs can also be lost to beach erosion. At Sandy Point NWR, 40 percent to 60 percent of the eggs laid each year would be lost to erosion if not for human intervention [2]. Because leatherbacks nest in the tropics during hurricane season, there is also potential for storm-related loss of nests. In 1980, only four out of approximately 80 nests laid on Sandy Point NWR survived to hatch following the catastrophic effects of Hurricane Allen [2]. Finally, there is a growing concern that essential beach nesting habitat will be innundated by global warming-induced sea level rise.

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Leatherback Turtle, (Dermochelys coriacea). Silver Spring, MD. 66pp.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Recovery Plan for Leatherback Turtles, (Dermochelys coriacea) in the U.S. Caribbean, Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. Washington, D.C.1992. 60 pp + appendices.

[3] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A.

[4] Rabon, D. R. Jr., S. A. Johnson, R. Boettcher, M. Dodd, M. Lyons, S. Murphy, S. Ramsey, S. Roff, and K. Stewart. 2003. Confirmed Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) Nests from North Carolina, with a Summary of Leatherback Nesting Activities North of Florida. Marine Turtle Newsletter 101:4-8.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2001. Stock Assessment of Leatherback Sea Turtles of the Western North Atlantic.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Leatherback Sea Turtle {Dermochelys coriacea). Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/leatherback.html) accessed December, 2005.

[7] Kaplan, I.C. 2005. A Risk Assessment for Pacific Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 62(8):1710-1719.

[8] Endangered Species Technical Bulletin 22(3):25.

[9] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Research Institute. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available online at http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/. Accessed April 2, 2012.

Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Atlantic DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 7/10/2001 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(b), DE(b), FL(s), GA(s), LA(s), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MS(s), NH(b), NY(b), NJ(b), NC(b), PR(s), RI(b), SC(b), TX(s), VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

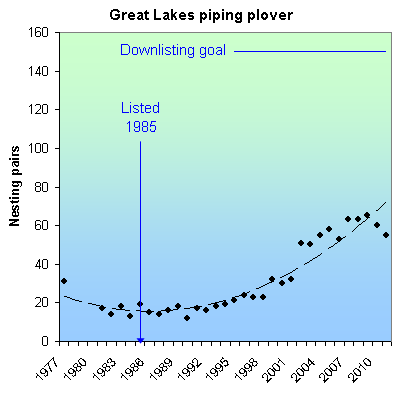

Atlantic piping plover populations initially declined due to hunting and the millinery trade. With these eliminated, it increased in the first half of the 20th century, but began declining after 1950 due to development, beach crowding and predation. It was listed as 1985 after which intensive habitat protection and control of recreationists and predators, increased its U.S. population from 550 pairs in 1986 to 1,550 in 2011, reaching its overall U.S. recovery goal in 3 of the last 5 years.

RECOVERY TREND

The Atlantic piping plover (Charadrius melodus) breeds on Atlantic coastal beaches from Newfoundland to northernmost South Carolina [1]. Hunters and the millinery trade decimated the species in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were stopped by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The plover steadily recovered until about 1950, then began to decline again under pressure from development, beach stabilization programs, increased recreation, and anthropogenically caused increases in predation by native and introduced species.

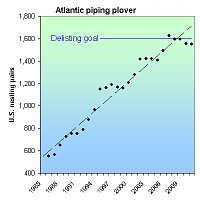

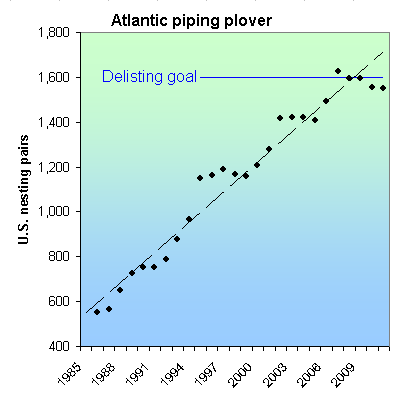

Following its listing as an endangered species in 1985, the plover was subject to intense nest site, nest area, and predator management programs, resulting in the following population growth between 1986 and 2011 [1, 2, 3]:

POPULATION 1986-2011 GROWTH RECOVERY GOAL YEARS AT RECOVERY GOAL

Canada: 240 - 209 pairs 400 pairs 0

New England 184 - 825 pairs 625 pairs At least 100% of goal, last 14 years

New York/New Jersey: 208 - 431 pairs 575 pairs At least 90% of goal, 6 of last 9 years

South Atlantic: 158 - 294 pairs 400 pairs 0

U.S. population: 550 - 1,550 pairs 1,600 pairs At least 100% of goal, 3 of last 5 years

Total: 790 - 1,759 pairs 2,000 pairs At least 87% of goal, last six years

The 1996 federal recovery plan [1] established the following delisting criteria: 1) Increase and maintain for five years a total of 2,000 breeding pairs, distributed among four recovery units as follows: Canada, 400 pairs; New England, 625 pairs; New York-New Jersey, 575 pairs; Southern (DE-MD-VA-NC), 400 pairs. 2) Verify the adequacy of a 2,000-pair population of piping plovers to maintain heterozygosity and allelic diversity over the long term. 3) Achieve five-year average productivity of 1.5 fledged chicks per pair in each of the four recovery units described in criterion 1, based on data from sites that collectively support at least 90 percent of the recovery unit’s population. 4) Institute long-term agreements to assure protection and management sufficient to maintain the population targets and average productivity in each recovery unit. 5) Ensure long-term maintenance of wintering habitat, sufficient in quantity, quality and distribution to maintain survival rates for a 2,000-pair population.

- The New England unit exceeded its recovery plan goal of 625 nesting pairs each of the 14 years between 1998 and 2011 and cointinues to grow.

- The New York/New Jersey unit grew steadily from 1986 to 2007, the only year in which it reached its recovery plan goal. It declined in all years from 2008 to 2011. While it has been at at least 90% of its goal in six of the nine years ending in 2011, the recent declines are worrisome.

- The Southern recovery unit was relatively stable betwee 1986 and 2003, grew rapidly between 2004 and 2008, then remained relatively stable at a reduced level from 2009 to 2011. It has never reached its recovery goal and has always been the smallest and slowest growing of the three U.S. recovery units.

- The U.S. population as a whole had strong, steady growth between 1986 and 2007, increasinging from 550 to 1,624 pairs. 2007 was the first year it reached its recovery goal of 1,600 pairs. From 2009 to 2011, it declined slightly to 1,550 pairs. The U.S. trend is dominated by the New England recovery unit which is the largest, fastest and most consistently growing.

- The Canadian recovery unit has periods of growth and decline, but remained at 200-250 nesting pairs in almost all years between 1986 and 2011. It the smallest of all the recovery units and the only one not to have experienced net growth since 1986.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), Atlantic Coast Population, Revised Recovery Plan. Hadley, Massachusetts. 258 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Abundance and productivity estimates – 2010 update: Atlantic Coast piping plover population. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/pdf/Abundance&Productivity2010Update.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Preliminary 2011 Atlantic Coast Piping Plover Abundance and Productivity Estimates, March 20, 2012. Sudbury, MA. Available at http://www.fws.gov/northeast/pipingplover/preliminary2011%2020March2012%20for%20AC%20website.pdf

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 214 pp.

Bald eagle (continental U.S. DPS) (Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Continental U.S. DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(b), AZ(b), AR(b), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(b), FL(b), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(b), KY(b), LA(b), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(b), MO(b), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(b), OH(b), OK(b), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(b), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

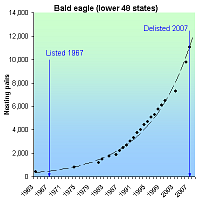

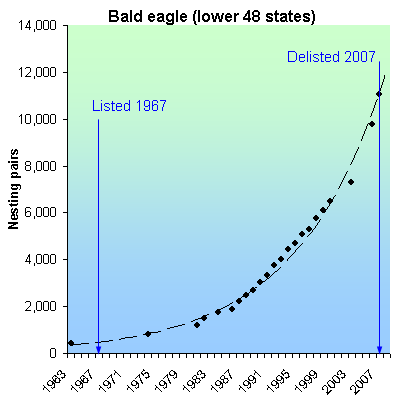

The bald eagle declined throughout the lower 48 states, and was extirpate from most of them due to habitat loss, persecution, and DDT-related eggshell thinning. The banning of DDT, increased wetland protection and restoration, and an aggressive, mostly state-based reintroduction program caused eagle pairs to soar from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when the eagle was removed from the endangered list.

RECOVERY TREND

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) first declined in the 1800s at the hands of trophy hunters, feather collectors, and wanton killing [1]. It was already extirpated or at low numbers in most states by the 1940s when DDT and other organochlorines became widely used. DDE, a breakdown product of DDT, accumulates in the fatty tissue of female eagles, impairing the formation of calcium needed for normal egg formation, causing a decline in reproductive success. DDT caused eagle numbers plummet further, and in 1967 the species was listed as endangered in the lower 48 states [1].

The eagle was joined on the list by the American peregrine falcon, Arctic peregrine falcon and brown pelican in 1970. The listing of these large, charismatic birds rallied the nation to band the production and sale of DDT in 1972.

Due to the DDT ban, increased habitat protection, and aggressive captive breeding and translocation programs (mostly run by state wildlife agencies), bald eagle pairs in the lower 48 soared from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when it was removed from the threatened species list [2, 7]. In 1984, 13 states lacked nesting eagles. By 1998, it was absent from only two. By 2006, it nested in all 48 states [7].

The eagle was proposed for delisting in 1998 [1] and again in 2006 [4]. It was downlisted in 1995 and delisted in 2007 [6].

The bald eagle is managed under five federal recovery plans, divided by region:

Chesapeake Recovery Region: Virginia east of Blue Ridge Mountains, Delaware, Maryland, the eastern half of Pennsylvania, West Virginia Panhandle and two-thirds of New Jersey. Delisting goals were met in 1996 [1]. As of 2003, there were more than 800 nesting pairs in this region [4].

Northern States Recovery Region: 25 Northernmost states. Delisting goals were met in 1991, with 1,349 occupied breeding areas across 20 states. As of 2007, there were an estimated 4,215 breeding pairs in the northern recovery region [6].

Pacific Recovery Region: Idaho, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Montana and Wyoming. Numeric delisting goals were met in 1995 [1]. As of 2001, there were

1,627 nesting pairs in this recovery region [4].

Southeastern Recovery Region: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and eastern Texas. Downlisting goals were met between 1991 and 1998. More than 1,700 pairs were counted in 2000 [4, 6].

Southwestern Recovery Region: Oklahoma and Texas west of the 100th meridian, New Mexico, Arizona and California bordering the Lower Colorado River. The goal established in the recovery plan has been exceeded. In 2003, 46 occupied breeding areas were reported in New Mexico and Arizona. In 2004, the Arizona had 41 occupied breeding areas [4].

In the eight Northeast states from New Jersey to Maine and Vermont, nesting eagle pairs increased from 21 in 1967 to 562 in 2005 [5]. The majority were in Maine, which supported all 21 pairs in 1967 and 385 pairs in 2005. Eagles returned to Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1990, with the former supporting 19 pairs in 2005 and the latter eight in 2004. In 2005 there were 53 pairs in New Jersey, 94 in New York and one in Vermont. The Northeast is also an important wintering area, with the Connecticut population increasing from 20 to 92 between 1979 and 2005, and the New York population increasing from six to 194 between 1978 and 2006 [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Proposed rule to remove the bald eagle in the Lower 48 states from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register, July 6, 1999 (64 FR 36453)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Bald Eagle Numbers Soaring. May 14, 2007 press release.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Removing the bald eagle in the Lower 48 States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife; reopening of public comment period with new information. Federal Regiter, February 16, 2006 (71 FR 8238).

[5] Center for Biological Diversity. 2006. Bald eagle trends in the Northeastern United States. Tucson, AZ.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Removing the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Final Rule. 72 Fed. Reg 37346.

[7] Suckling, K. and W. Hodges. Status of the bald eagle in the lower 48 states and the District of Columbia: 1963-2007. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ. Available at http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/bald_eagle/report/index.html.

Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 10/23/1998 |

Range: AK(s), CA(s), FL(o), HI(s), ME(o), MD(o), MA(o), NH(o), NY(o), NC(o), OR(m), RI(o), SC(o), WA(m) ---

SUMMARY

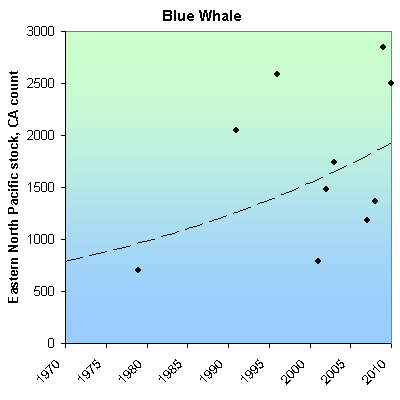

The blue whale population was reduced by as much as 99 percent due to whaling that occurred before the mid-1960s. The number of whales reported off the coast of California, the largest stock in U.S. waters, increased from 704 in 1980 to an estimated 2,497 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal ever known to have lived on Earth [1]. Blue whales are found in all oceans worldwide and are separated into populations from the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere [1]. Each population is composed of several stocks that typically migrate between higher-latitude summer feeding grounds and lower-latitude wintering areas. The largest numbers of blue whales in U.S. waters are within the eastern North Pacific stock. Other U.S. stocks occur in waters off the coast of Hawaii and the Northeast [1].

Pre-whaling blue whale populations had about 350,000 individuals [3]. In 1868, the invention of the exploding harpoon gun made the hunting of blue whales possible and in 1900, whalers began to focus on blue whales and continued until the mid 1960s [1, 3]. During this time, it is estimated that whalers killed up to 99 percent of blue whale populations [3]. Currently, there are about 5,000-10,000 blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere and about 3,000-4,000 in the Northern Hemisphere [3]. Current threats include collisions with vessels, entanglement in fishing gear, reduced zooplankton production due to habitat degradation, and disturbance from low-frequency noise [1]. The offshore driftnet gillnet fishery is the only fishery likely to take blue whales, but few mortalities or serious injuries have been observed [2].

EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

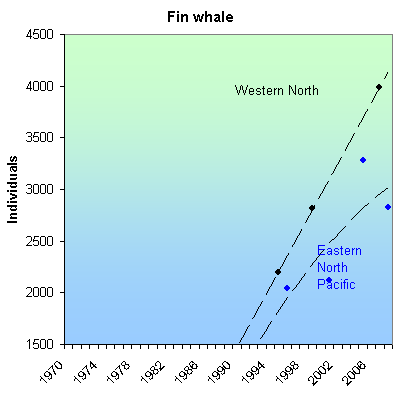

The Eastern North Pacific Stock feeds in waters off the coast of California from June to November and then migrates south to Mexico (sometimes going as far south as Costa Rica) in winter/spring [2]. Recently, blue whales seen off the coast of Alaska were photo-matched to photos from the Southern California area, indicating that California animals now migrate as far north as Alaska [4]. This is probably a reestablishment of a traditional migratory route [4]. The number of whales reported off the coast of California increased from 704 in 1979/80 to 2497 in 2010 [2, 11]. It is not certain if the overall increasing trend indicates a growth in the size of the stock, or just increased use of California waters [2], but in general, the stock is thought to have increased [1]. Because this is the largest stock in U.S. waters, it dominates the trend of the species in U.S. waters.

WESTERN NORTH PACIFIC STOCK

Blue whales feeding along the Aleutian Islands are probably part of a central western North Pacific stock that is thought to migrate to offshore waters north of Hawaii in winter [5]. Sightings of blue whales in Hawaiian waters are infrequent, although acoustic recordings indicate that blue whales occur there. There are no estimates of population size for this stock [5]. No blue whales were sighted during aerial surveys of Hawaiian waters conducted from 1993 to 1998 or during shipboard surveys conducted in the summer/fall of 2002 [5]. In 2004, three blue whales were seen in the western Aleutians, the first U.S. sightings of blue whales from this western North Pacific population in several decades [6]

NORTH ATLANTIC STOCK

The blue whale is an occasional visitor along the Atlantic coast of the Northeast [7]. Sightings of blue whales off Cape Cod, Mass., in summer and fall may represent the southern limit of the feeding range of the western North Atlantic stock that feeds primarily off the Canadian coast [7]. Blue whales have been sighted as far south as Florida, however, and the actual southern limit of this stock’s range is unknown [7]. Because blue whales are not frequently seen in U.S. Atlantic waters, there are insufficient data to determine the stock's population trend [7]. In 1997, the total number of photo-identified individuals for eastern Canada and New England was 352 [1].

CITATIONS

[1] NMFS. 1998. Recovery plan for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Prepared by Reeves R.R., P.J. Clapham, R.L. Brownell, Jr., and G.K. Silber for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 42 pp.

[2] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[3] American Cetacean Society. 2005 American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Website http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bluewhl.htm (accessed on 11/30/05).

[4] NOAA. Fisheries. 2004. NOAA Scientists Sight Blue Whales in Alaska. Press Release 7/27/2004.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2004. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Pacific Stock. Revised 3/15/05. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[6] Rankin, Barlow and Stafford. (in press) Marine Mammal Science.

[7] NOAA Fisheries. 2002. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Western North Atlantic Stock. Revised Jan. 2002. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C

[8] NOAA Fisheries. 2007. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[9] NOAA Fisheries. 2008. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] NOAA Fisheries. 2009. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

[11] NOAA Fisheries. 2010. Stock Assessment Report. Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C.

Brown pelican (Eastern DPS) (Pelecanus occidentalis (Atlantic/Eastern Gulf Coast DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1980 |

Range: AL(b), CT(o), DE(s), FL(b), GA(b), ME(o), MD(b), MA(o), NH(o), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), RI(o), SC(b), VA(b) ---

SUMMARY

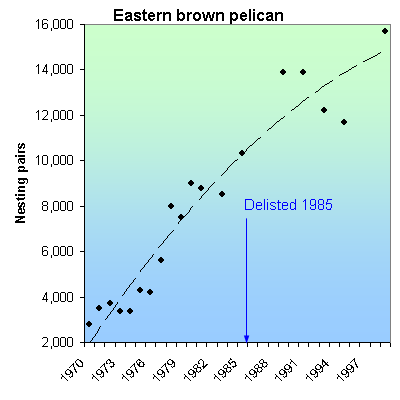

Reproductive failure due to eggshell thinning, caused by the pesticide DDT, was the main cause of brown pelican population declines. The pelican has recovered, but now faces threats from offshore oil and wind development, rising sea levels and hurricanes. Brown pelican nests on the Atlantic Coast increased from 2,796 in 1970 to 15,670 in 1999; on the eastern Gulf Coast, nest numbers increased slightly from 5,100 in 1970 to 5,682 in 1999. The eastern brown pelican was delisted in 1985 due to recovery.

RECOVERY TREND

The southeastern brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis pop.) breeds from Maryland south along the Atlantic Coast to southern Florida and westward along the Gulf Coast to Alabama [1]. The brown pelican occurs regularly as a non-breeder in New York, New Jersey and Delaware, and occasionally northward to Nova Scotia.

The listing history of this population is complex. The brown pelican species was listed as endangered throughout its range in 1970. The "southeastern brown pelican," a taxon not previously recognized by scientists or wildlife managers, was separated from the rest of the species, declared recovered, and delisted in 1985 [1]. This distinct population includes, and is limited to, all portions of the eastern brown pelican (P. o. carolinensis) east of Mississippi.

Nests on the Atlantic Coast increased from 2,796 in 1970 to 10,300 in 1985, when it was delisted, and numbered 15,670 in 1999. Nests on the Gulf Coast (eastern and western) increased from 5,100 in 1970 to 7,000 in 1985 when the Eastern Gulf Coast population was delisted, then continued increasing to 24,400 in 1999.

MARYLAND: Prior to 1987, when six pairs nested on a state-owned dredge spoil island in Chincoteague Bay near Assateague Island, the brown pelican had not been recorded nesting in Maryland [3,4]. Nesting pairs increased from 26 in 1989 to 1,042 in 2008 [5].

VIRGINIA: The brown pelican was not recorded as nesting in Virginia prior to 1987 [4]. Nests increased from 37 in 1989 to 1,406 in 1999 [2]. In 2008 there were 1,924 breeding pairs in the state [6].

NORTH CAROLINA: Nests increased from 75 in 1976 [1] to 4,350 in 1999 [2]. In 2007 there was a marked decrease to 3,452 nests [7].

SOUTH CAROLINA: Nests increased from 1,117 in 1970 [1] to 7,739 in 1989, then decreased to 3,486 in 1999 [2]. The latter decline is believed to be the result of key island habitats eroding away. The birds likely moved to other states. In 2009 there were 3,985 nests [8].

GEORGIA: The first record of nesting pelicans was in 1988 [2]. Nests increased from 200 in 1989 to around 3,500 nests in 2007 [2,9].

FLORIDA: Nests increased from 7,690 in 1970 [1] to 12,312 in 1989 [2], then decreased to only 4,724 nesting pairs in 2007 [10], which is the lowest number of nests recorded in the state since before 1970.

ALABAMA: The brown pelican was not recorded to nest in Alabama prior to 1983 [1]. Nests increased from 588 in 1989 to around 5,000 as of 2006 [11].

NEW JERSEY: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer. Several pairs unsuccessfully attempted to nest in 1992 and 1994 [2].

NEW YORK: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer, but have not been recorded nesting [2].

DELAWARE: Beginning in the 1980s, brown pelicans were seen with some regularity during the summer, but have not been recorded nesting [2].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Removal of the brown pelican in the southeastern United States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register (50:4938).

[2] Shields, M. 2002. Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 609 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

[3] USGS. 2005. Biological and ecotoxicological characteristics of terrestrial vertebrate species residing in estuaries. U.S. Geological Survey. Website (www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bioeco/bpelican.htm) accessed December 30, 2005.

[4] Brinker, D.F. 2006. Brown pelican nesting in Maryland, 1986-2005. Data provided by David Brinker, Natural Heritage Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Cantonsville, MD, January 3, 2006.

[5] Maryland Department of Natural Resources. 2008. Creature Feature: Brown Pelican. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mydnr/creaturefeature/brownpelican.asp

[6] Watts, B. D. and B. J. Paxton. 2009. Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in

coastal Virginia: 2009 breeding season. CCBTR-09-03. Center for Conservation Biology, College of William and Mary/Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA 21 pp.

[7] North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. 2008. Annual Program Report 2007-2008. Wildlife Diversity Program Division of Wildlife Management. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://www.ncwildlife.org/Wildlife_Species_Con/documents/AnnualProgramReportWDinWM07-08.pdf

[8] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR). 2010. Untitled population data provided to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Obtained via FOIA FWS-2010-00941.

[9] Jodice, P.G.R., T.M. Murphy, F.J. Sanders, and L.M. Ferguson. 2007. Longterm Trends in Nest Counts of Colonial Seabirds in South Carolina, USA.

[10] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2007. Fiscal Year 2006-2007 Progress Report on activities of the Endangered and Threatened Species Management and Conservation Plan. Accessed July 27, 2010 at: http://www.myfwc.com/docs/WildlifeHabitats/Endangered_Threatened_Species_Progress_Report_2006_2007.pdf#search=%22brown%20pelican%2

[11] Morley, D.F. 2006. 2006 Alabama Coastal BirdFest. Conservation News, Alabama Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources. Accessed August 2, 2010 at: http://www.outdooralabama.com/outdoor-alabama/07-06news.pdf.

Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 6/8/1993 |

Range: DE(b), MD(b), PA(b), VA(b) --- NJ(x)

SUMMARY

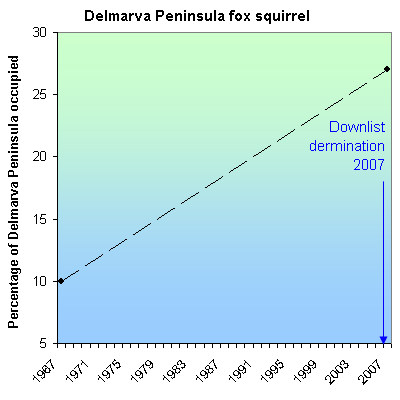

Logging and conversion of forests to farms and developments destroyed much of the Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel's habitat. The squirrel remains threatened by ongoing habitat loss, car strikes and rising sea levels due to global climate change. At the time of listing in 1967, the squirrel occupied only 10 percent of the Delmarva Peninsula. As of 2007, its likely occupied range had expanded to 27 percent of the peninsula. In addition, 11 of 16 translocations have been successful.

RECOVERY TREND

The Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereusis) is a large, heavy-bodied tree squirrel with an unusually full, fluffy tail [1]. Historically, it occurred in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, south-central New Jersey, eastern Maryland, and the Virginia portion of the Delmarva Peninsula [2]. Because the species' habitat requirements are somewhat specific, requiring mature park-like forests, it is likely that populations were scattered and discontinuous. As forests were logged or converted to farms, they became unsuitable for the fox squirrel. As forests regrew, they were cut again before the mature forest required by fox squirrels could develop. By the turn of the century, the Delmarva fox squirrel had disappeared from New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Virginia, and by 1936, it disappeared from Delaware as well.