American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/3/1979 |

Range: AL(b), AR(b), FL(b), GA(b), LA(b), MS(b), NC(b), OK(b), SC(b), TX(b) ---

SUMMARY

Habitat loss and poorly regulated hunting resulted in the decline of American alligator populations. Following listing in 1967, populations rebounded, and the American alligator recovered. It remains protected due to similarity of appearance to the endangered American crocodile.

RECOVERY TREND

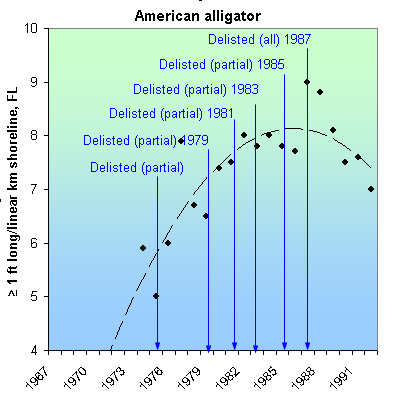

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) suffered noticable population declines by the 1950s and 1960s due to habitat loss and unregulated or poorly regulated hunting [1]. In 1967 it was listed as an endangered species throughout its range in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas. Populations began to rise and the species was delisted in three Louisiana parishes in 1975 [2]; downlisted in Florida and certain coastal areas of South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas in 1977 [3]; delisted in nine additional Louisiana parishes in 1979 [4]; delisted in the 52 remaining Louisiana parishes in 1981 [5]; delisted in Texas in 1983 [6]; delisted in Florida in 1985 [7]; and delisted in the remaining portion of its range (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma and South Carolina) in 1987 [1]. To protect it from accidental shooting, it remains protected under the Endangered Species Act due to its similarity of appearance to the endangered American crocodile [1].

Alligator surveys are generally not comparable due to differences in effort and methodology. Florida established a standardized monitoring program in 1974 that documented an increased density of wild alligators over one foot in length per linear kilometer of shoreline between 1974 and 1992 [8]. The density peaked in 1987 at nine/km and thereafter declined to seven/km in 1992.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1987. Reclassification of the American alligator to threatened due to similarity of appearance throughout the remainder of its range. June 4, 1987 (52 FR 21059)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1975. Reclassification of the American alligator in Louisiana, and proposed changes to special rules concerning the alligator. September 26, 1975 (40 FR 44412)

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1977. January 10, 1977 (42 FR 2071)

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1979. June 25, 1979 (44 FR 37130)

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1981. Reclassification of American alligator in Louisiana. August 10, 1981 (46 FR 40664)

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983. October 12, 1983 (48 FR 46332)

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Reclassification of American alligator in Florida to threatened due to similarity of appearance. June 20, 1985 (50 FR 25672).

[8] Woodward, A.R. and C.T. Moore. 1995. American Alligators in Florida; in LaRoe, E.T., G.S. Farris, C.E. Puckett, P.D. Doran, and M.J. Mac, eds. 1995. Our living resources: a report to the nation on the distribution, abundance, and health of U.S. plants, animals, and ecosystems. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Service, Washington, DC. 530 pp. http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/d052.htm.

American crocodile (Florida DPS) (Crocodylus acutus (Florida DPS))

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 9/24/1976 |

| Listed: 9/25/1975 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: FL(b) ---

SUMMARY

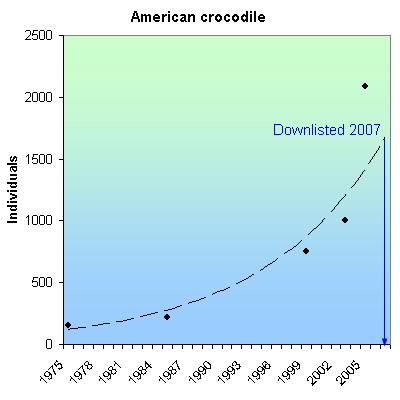

The American crocodile declined due to hunting and habitat loss to development. The population rebounded from approximately 350 crocodiles in Florida in 1975 to 2,085 as of 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) occurs along the Atlantic coast from southern Florida to northern South America and along the Pacific coast of Central America [4]. The species was hunted for its skin and for sport, and was over collected for zoos and museums [4].

The size of the pre-Columbian American crocodile population in Florida is not well-known, but may have been 2,000 to 3,000 non-hatchlings [3]. Development and hunting reduced it to 1,000 to 2,000 individuals by the early 20th century [1] There were 200 to 400 crocodiles in Florida when it was listed as endangered in 1975, and just 10 to 20 breeding females by 1975 [4, 6]. The population grew to about 2,085 as of 2005 in 2003 [5].

In 1975, the American crocodile was limited to a small area of northeastern Florida Bay [1, 5]. As of 2005, it encompassed much of the historic Florida range including Key Largo, Biscayne Bay, Florida Bay, the southwestern coast and Marco Island [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. South Florida Multi-Species Recovery Plan. Atlanta, GA. Available at www.fws.gov/southeast/vbpdfs/species/reptiles/amcr.pdf

[2] University of Florida. 2003. UF Crocodile Survey To Yield Information About Everglades Health. January 29, 2003 Press Release, Available at <http://news.ufl.edu/2003/01/29/crocodilesurvey>.

[3] Wolkomir, R. and J. Wolkomir. 2005. The comback of the crocodiles. Wildlife Conservation (online edition). Available at <http://www.wildlifeconservation.org/wcm-home/wcm-article/14597905>.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Reclassification of the American crocodile distinct population segment in Florida from endangered to threatened. March 20, 2007 (70 FR 15052).

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Proposal for Reclassifying the American crocodile distinct population segment in Florida From endangered to threatened and initiation of a 5-year review. March 24, 2005 (70 FR 15052).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1975. Listing of the Florida population of the the American crocodile as an endangered species. September 25, 1975 (40 FR 44149).

Atlantic green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas mydas)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(s), DE(m), FL(b), GA(b), LA(s), MA(s), MS(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), TX(s), VI(b), VA(m) ---

SUMMARY

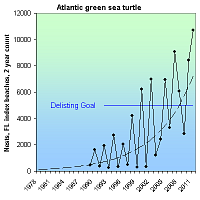

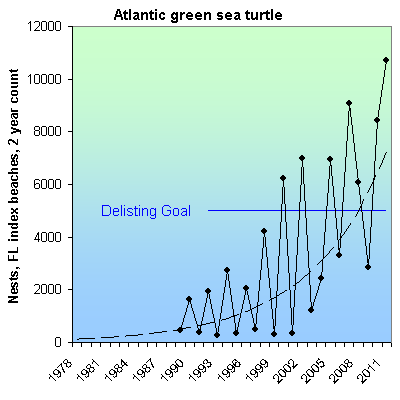

The Atlantic green sea is threatened by egg collection, hunting, vandalism, disturbance while nesting, beach development, habitat loss, and sea level rise. Its population has increased in the United States since being listed as endangered in 1978, but systematic surveys only began in 1989. It grew by 2,206% in Florida between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) and has achieved its population size recovery goal.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 2]. It migrates enormous distances between foraging and nesting areas [2]. When not migrating, the green sea turtle’s typical near-shore habitat includes shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets [1]. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches [3]. Females generally breed every two or more years, and nest an average of three to four times per breeding year [4].

Exploitation of the green sea turtle, its eggs and its habitat resulted in population declines [1]. Although green sea turtle populations continue to decline throughout much of their range due to directed harvest (both illegal and legal), incidental capture in near-shore gillnets, and negative impacts on essential habitats [1], two populations that nest in the United States (Florida and Hawaii) have increased in size since the species was placed on the endangered list in 1978 [3].

Green sea turtle populations in the U.S. Atlantic occur from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean [1, 2]. In the U.S. Pacific, green sea turtles occur from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 2]. Atlantic green sea turtles are variously considered a population and a subspecies (Chelonia mydas mydas) [1]. In the U.S. Atlantic, nesting occurs primarily on beaches along Florida’s east coast, although smaller numbers of nests can be found in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico [5]. Foraging occurs in the Gulf of Mexico to Texas and along the Atlantic Coast to Massachusetts [1].

CARIBBEAN

Reliable, long-term nesting data are unavailable for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands [8]. The number of green turtle nests has remained low for all the islands, but there appears to have been a gradual increase in the numbers of juveniles observed in foraging grounds since the mid-1970s [8]. The largest concentration of nests occurs on St. Croix, where an average of 100 were counted per year between 1980 and 1990. Waters surrounding the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico have been designated critical habitat [1].

FLORIDA

State-wide population counts have been conducted in Florida since the 1970s, but are not strictly controlled for survey effort and area, especially in the early years. Thus while it is known that Florida's nesting green sea turtle population has increased since the 1970s, it is not possible to determine by how much. Standardized surveys on a large number of "index beaches" was initiated in 1989. They demonstrate that the number of annual green sea turtle nests increased by 2,206% between 1989 and 2011 (464 to 10,701) [4].

The number of green sea turtle nests in Florida (and in many other places), generally alternates between high and low years. Between 1989 and 2001, the number of nests in low years remained flat (250-500). Between 2003 and 2011 it grew sharply. Nesting in high years grew throughout 1989-2011, but more sharply starting in 1998.

An unusually low count in 2004 was caused by a hurricane. The biennial cycle was broken in 2009 and 2011, resulting in the highest recorded count in what should have been a low year (2011 = 10,701). It is possible to predict at this point if 2012 will be a high or low year.

NORTHERN STATES

Each winter green, Kemps Ridley and loggerhead sea turtles migrating southward from northeastern waters are regularly stranded on shores of Cape Cod Bay between Brewster and Truro [7]. These turtles die of hypothermia if not rescued. The total number of strandings ranged between 49 and 281 turtles between 1995 and 2003. Green sea turtle strandings ranged from zero to seven each year [7]. A volunteer program has been established to rescue, rehabilitate and release the turtles in Florida.

In 2005, the first verified green sea turtle nest was found in Virginia. A few females previously had laid eggs on beaches as far north as North Carolina's Outer Banks [10].

RECOVERY PLAN

In order for the green sea turtle to be delisted, the 1991 federal recovery plan requires that Florida supports an average of 5,000 nests over six consecutive years [1]. This criterion was met in 2009, 2010, and 2011 on the index beaches. As these are a subset of all nesting beaches, the delisting criteria was met in at least all years between 2007 and 2011.

The recovery plan also requires that 2) at least 105 kilometers of nesting beach be in public ownership and support at least 50 percent of U.S. nests, and 3) a reduction in stage-class mortality results in an increase in individuals in foraging grounds [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. Washington, DC.

[2] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Silver Spring, Maryland.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Office. Website (http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/Green-Sea-Turtle.htm) accessed January, 2006.

[4] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available at (http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/, accessed May, 2012).

[5] National Marine Fisheries Service. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). Threatened Species Account. Endangered Florida and Mexican Breeding Populations. NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Silver Spring, MD. Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/green.html) accessed January, 2006.

[6] Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. 2006. Florida's index nesting beach survey data. Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission,. Website (http://research.myfwc.com/features/view_article.asp?id=10690) accessed January, 2006.

[7] Lewis, D. Photo diary of a terrapin researcher. Website (http://terrapindiary.org/) accessed January 7, 2006.

[8] Hillis-Starr, Z.M., R. Boulon, M. Evans. Sea turtles in the Virgin Islands in Status and trends of the Nation's Biological Resources, USGS. Available at (http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/cr136.htm, accessed January, 2006.)

[9] Orlando Sentinel. August 6, 2005. Green Sea Turtle makes odd egg-laying visit to Virginia. Page A20.

Atlantic hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 9/2/1998 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(s), CT(o), DE(o), FL(b), GA(o), LA(s), MD(o), MA(o), MS(s), NY(o), NJ(o), NC(o), PR(b), RI(o), SC(o), TX(s), VI(b), VA(o) ---

SUMMARY

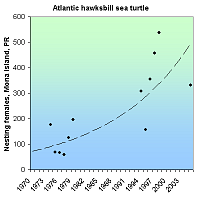

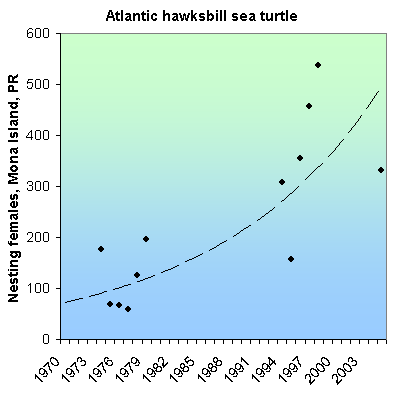

Globally, the number of hawksbill sea turtles may have declined by as much as 80 percent over the past century due to commerce in their shells, poaching, habitat loss, bycatch and entanglement in marine debris. Although hawksbill numbers continue to decline globally, at protected beaches on Mona Island, Puerto Rico, nests increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005.

RECOVERY TREND

Hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricatause) use different habitats at different stages of their life cycle [1]. Post-hatchling hawksbills occupy pelagic environments, taking shelter in weedlines that accumulate at convergence zones [1]. They reenter coastal waters when they reach approximately 20 to 25 centimeters carapace length [1]. Coral reefs are used as resident foraging habitat by juveniles, subadults and adults [1]. Along the eastern shores of continents where coral reefs are absent, hawksbills are known to inhabit mangrove-fringed bays and estuaries [1]. They feed primarily on sponges [1, 2]. Female hawksbills nest on low- and high-energy beaches of tropical oceans. Throughout their range, hawksbills typically nest at low densities with aggregations consisting of a few dozen, or at most a few hundred individuals [1]. Nests have been found on both insular and mainland beaches where nests are typically placed under vegetation [1]. Migratory patterns of hawksbills are not well known, although a reproductive migration is thought to take place [1, 2].

Hawksbills occur in tropical and subtropical seas of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans and nest on beaches in at least 60 different nations [3]. Along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the continental U.S., hawksbills have been reported by all of the Gulf states and from as far north as Massachusetts, although sightings north of Florida are rare [1]. Representatives of at least some life-history stages regularly occur in southern Florida (where the warm Gulf Stream current passes close to shore) and the northern Gulf of Mexico (especially Texas), in the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and along the Central American mainland south to Brazil [1].

The largest remaining concentrations of nesting hawksbills occur on the beaches of remote oceanic islands of Australia and the Indian Ocean [1]. The Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico also supports a significant population of nesting hawksbills [1]. Within U.S. jurisdiction, nesting occurs principally on beaches in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The most important nesting sites are Mona Island (Puerto Rico) and Buck Island (St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands) [1]. Within the continental United States, nesting is restricted to the southeastern coast of Florida and the Florida Keys, where one or two nests have been reported annually [1].

Quantitative data on population changes of hawksbills are scarce, in part because hawksbills were already greatly reduced in number when scientific studies of sea turtles began in the late 1950s [3]. In addition, visual evidence of hawksbill nesting is the least obvious among the sea turtle species, because hawksbills often select remote pocket beaches with little exposed sand to leave traces of revealing crawl marks [1]. An estimate of the minimum number of female hawksbills in 1989 indicated that at least 15,000 to 25,000 female hawksbills nested annually worldwide [4]. Although global numbers are very difficult to estimate, it appears that this turtle has suffered drastic decline, probably by as much as 80 percent over the last century (3). Only five regional populations, Seychelles, Mexico, Indonesia, and two in Australia, support more than 1,000 nesting females annually [3]. Hawksbill populations are either known or suspected to be declining in 38 of the 65 geopolitical units for which nesting density estimates are available [3].

CARIBBEAN

Hawksbill populations in the Western Atlantic-Caribbean region are thought to be greatly depleted [3]. In the Caribbean region, the number of females nesting annually is about 5,000 (order-of-magnitude estimate) [3]. With few exceptions, all of the countries in the Caribbean report fewer than 100 females nesting annually [3]. The largest known nesting concentrations are in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico [3]. These populations may be increasing [3]. A total of 4,522 nests were recorded in the states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo in 1996, compared to only a few hundred in the early 1980s [5].

In the U.S Caribbean, there is evidence that hawksbill nesting populations have been severely reduced during the 20th century [1]. Estimates of the size of nesting populations under U.S. jurisdiction are available for only a few localities [1]. Although trends are uncertain due to long intervals between hawksbill nesting generations (hawksbill take between 30 and 40 years to reach sexual maturity) and fluctuations in the number of reproductive females that nest in a particular year [3], hawksbill numbers increased at two protected locations, Mona Island, Puerto Rico and at Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands [5]. The number of nests on Mona Island increased from 177 in 1974 to 332 in 2005 [5, 6]. On Buck Island, the number of nesting females increased from 73 in 1987 to 121 in 1998, and averaged 56 from 2001-2005 [5, 6].

International commerce in hawksbill shell (“tortoiseshell” or “bekko”) may be the most significant factor endangering hawksbill populations worldwide [1]. Despite protective legislation, international trade in tortoiseshell and subsistence use of meat and eggs continues in many countries [1]. Females and eggs are vulnerable to poaching on nesting beaches and nests are vulnerable to beach erosion [1]. Egg poaching is a serious problem in Puerto Rico and also occurs in the U.S. Virgin Islands [1]. The practice of beach armoring can prevent females from reaching suitable nesting sites and can result in the loss of dry nesting beaches [1, 2]. Many hawksbill nesting beaches in the Caribbean are privately owned and in jeopardy of being developed [1]. Sand mining is also a threat to nesting beaches throughout the Caribbean [1]. The extent to which hawksbills are killed or debilitated after becoming entangled in marine debris has not been quantified, but it is believed to be a serious and growing problem [1]. Incidental catch in finfish fisheries may also pose a serious threat and the ingestion of marine debris (i.e. plastic bags, styrofoam) can result in hawksbill mortality [1].

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Recovery Plan for Hawksbill Turtles in the U.S. Caribbean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico. St. Petersburg, Florida.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Silver Spring, MD.

[3] Meylan, A.B. and M. Donnelly. 1999. Status Justification for Listing the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) as Critically Endangered on the 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 3(2):200–224.

[4] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.

[5] Meylan. 1999. Status of the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Caribbean Region. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 3(2):177–184. Available at (http://www.iucn-mtsg.org/publications/cc&b_april1999/4.14-Meylan-Status.pdf).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.fws.gov/northflorida/SeaTurtles/Turtle%20Factsheets/PDF/Hawksbill-Sea-Turtle.pdf

Atlantic leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea (Atlantic population))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 3/23/1979 | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: CT(s), DE(s), FL(b), GA(b), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(b), PR(b), RI(s), SC(b), VI(b), VA(s) ---

SUMMARY

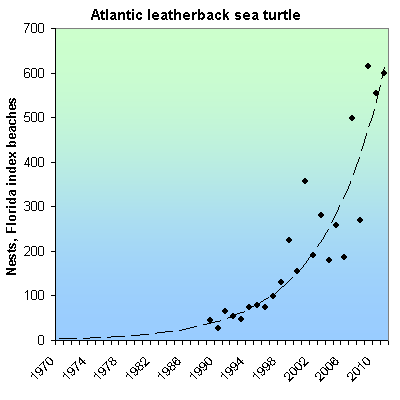

The Atlantic leatherback sea turtles declined due to habitat destruction, commercial fishery bycatch, harvest of eggs, hunting of adults, and loss of beach nesting habitat. It is still threatened by these, and in some places by offshore oil drilling. Globally, leatherback sea turtles have been declining for decades. U.S. populations, however, have increased since being listed as endangered in 1970. Between 1989 and 2011, nests at Florida core index beaches increased from 27 to 615.

RECOVERY TREND

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), the largest living turtle species, is a monotypic genus [1]. It is typically associated with continental shelf habitats and pelagic environments. Adult leatherbacks feed primarily on jellyfish in temperate and boreal latitudes, are highly migratory and have the most extensive range of any extant reptile [1]. Although their oceanic distribution is nearly worldwide, the number of nesting sites is few [3]. Gravid females emerge onto beaches to excavate nests and lay eggs. They prefer high-energy beaches with deep, unobstructed access, which occur most often along continental shorelines [2].

In the western Atlantic, leatherbacks nest from North Carolina to southern Brazil [4]. In U.S. waters, leatherbacks can be found along the East Coast from Maine to Florida, and in the Greater and Lesser Antilles [6]. Critical habitat has been designated as the nesting beaches and adjacent waters of Sandy Point, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands [2]. The Pacific population does not nest in the United States or its territories, but has important foraging areas on the West Coast and near Hawaii [1].

Although Atlantic leatherback populations under U.S. jurisdiction have increased in size since 1970, worldwide their numbers are decreasing. Leatherback numbers have declined in Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Trinidad, Tobago and Papua New Guinea [7]. In 1980 there were more than 115,000 adult female leatherbacks worldwide. In 2005, there were less than 25,000 [6]. The most precipitous declines have occurred in the Pacific Ocean [5]. One study estimated that the number of females in the eastern Pacific decreased from 91,000 in 1980 to 1,690 in 2000 [7]. The number of leatherback nests has also declined at all major nesting beaches throughout the Pacific [6]. Nesting along the Pacific coast of Mexico, which is estimated to represent about 50 percent of all nesting, declined at an annual rate of 22 percent over the last 12 years [6].

CARIBBEAN

In the western Atlantic and Caribbean, the largest nesting assemblages are found in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Florida. Nesting data for these locations have been collected since the early 1980s [6]. Nest numbers in Florida as well as on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Culebra Island, Puerto Rico, increased over the past 20 years [8]. At St. Croix, the number of nests deposited annually on Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, the largest nesting rookery in U.S. territory, ranged from 82 in 1986 to 260 in 1991 [2]. From 1979 on, the trend indicates a 7.5 percent increase per year (SE = 0.014).

FLORIDA

In Florida, several models estimated trends indicating a 9.1 percent increase per year (SE = 0.049) [2]. Florida has established counts on beaches used as "index beaches" where standardized counts have been conducted, allowing for more accurate comparisons between years and between beaches. From 1989 through 2011, leatherback nests at core index beaches numbered from 27 to 615 [9].

Habitat destruction, incidental catch in commercial fisheries, harvest of eggs and flesh, and offshore oil drilling continue to threaten to the survival of the Atlantic leatherback [6]. Entanglement and ingestion of marine debris, including abandoned nets, also pose a threat [1]. Artificial lights on nesting beaches can result in mortality in hatchling turtles by causing newly emerged hatchlings to become disoriented [1]. Eggs can also be lost to beach erosion. At Sandy Point NWR, 40 percent to 60 percent of the eggs laid each year would be lost to erosion if not for human intervention [2]. Because leatherbacks nest in the tropics during hurricane season, there is also potential for storm-related loss of nests. In 1980, only four out of approximately 80 nests laid on Sandy Point NWR survived to hatch following the catastrophic effects of Hurricane Allen [2]. Finally, there is a growing concern that essential beach nesting habitat will be innundated by global warming-induced sea level rise.

CITATIONS

[1] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Leatherback Turtle, (Dermochelys coriacea). Silver Spring, MD. 66pp.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Recovery Plan for Leatherback Turtles, (Dermochelys coriacea) in the U.S. Caribbean, Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. Washington, D.C.1992. 60 pp + appendices.

[3] NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A.

[4] Rabon, D. R. Jr., S. A. Johnson, R. Boettcher, M. Dodd, M. Lyons, S. Murphy, S. Ramsey, S. Roff, and K. Stewart. 2003. Confirmed Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) Nests from North Carolina, with a Summary of Leatherback Nesting Activities North of Florida. Marine Turtle Newsletter 101:4-8.

[5] NOAA Fisheries. 2001. Stock Assessment of Leatherback Sea Turtles of the Western North Atlantic.

[6] NOAA Fisheries. 2005. Leatherback Sea Turtle {Dermochelys coriacea). Website (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/leatherback.html) accessed December, 2005.

[7] Kaplan, I.C. 2005. A Risk Assessment for Pacific Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 62(8):1710-1719.

[8] Endangered Species Technical Bulletin 22(3):25.

[9] Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Research Institute. 2012. Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals (1989-2011). Available online at http://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/nesting/beach-survey-totals/. Accessed April 2, 2012.

Concho water snake (Nerodia paucimaculata)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 6/29/1989 | Listed: 9/3/1986 | Recovery plan: 9/27/1993 |

Range: TX

SUMMARY

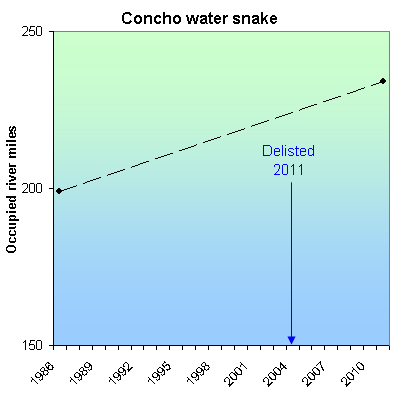

The Concho water snake became and endangered species due to range loss and the threat of future habitat loss and fragmentation from the construction of a reservoir. Between its 1986 listing and 2011 delisting, its range increased from 199 to 233 river and shoreline miles.

RECOVERY TREND

The fish-eating Concho water snake (Nerodia paucimaculata) is endemic to the Colorado and Concho Rivers in central Texas. It occurs in riffle areas in the Colorado River from E.V. Spence Reservoir to Colorado Bend State Park, including Ballinger Municipal Lake and O.H. Ivie Reservoir [1]. It also occurs on the Concho River from the City of San Angelo, Texas, to the river's confluence with the Colorado River at O.H. Ivie Reservoir [1].

The Concho water snake was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1986 due to threats to its water supply, habitat degradation from the construction of Ivie Reservoir, and isolation of its populations. At the time of listing, it was known to inhabit 199 river miles [1]. When declared recovered and delisted in 2011, the snake’s range consists of 233 miles of river and reservoir shoreline, though it had also disappeared from some reaches of its historical distribution upstream of San Angelo [1].

Total population estimates are not available due to high variation in sample efforts and environmental conditions over time [1]. Due an 2008 Memorandum of Understanding assuring adequate future water flows, habitat improvements, and assured connectivity between the snake’s three subpopulations, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the 1993 Recovery Plan goals had been met and removed the Concho water snake from the endangered species list in 2011.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Removal of the Concho Water Snake From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Removal of Designated Critical Habitat. 76 FR 66780.

Kemp's ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 12/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 9/22/2011 |

Range: AL(o), CT(s), DE(s), FL(o), GA(s), LA(m), ME(s), MD(s), MA(s), MS(m), NH(s), NY(s), NJ(s), NC(s), PR(o), RI(s), SC(o), TX(b), VI(o), VA(s) ---

SUMMARY

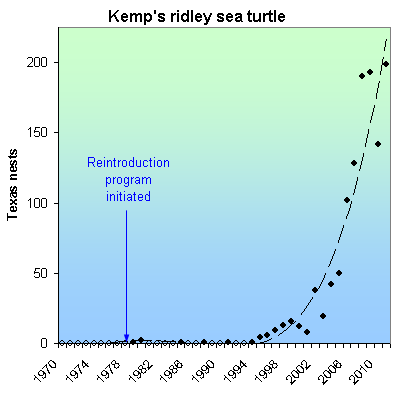

More than 40,000 Kemp's Ridley sea turtles once nested in a single day on one beach in Mexico, but egg collection, oil drilling, development, and commercial fishing extirpated it from the United States by the 1950s. It was listed as endangered in 1970 and was reintroduced to Texas in 1978. There was little progress until 1995. The population reached 199 in 2011. The Mexican population grew from a low of 740 in the mid-1980s to at least 11,600 nests in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

The Kemp's Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) nests only in the Gulf of Mexico [6]. Historical nesting areas are not well known, but have likely always been centered in Mexico. Even less is known about historic population numbers, but as late as 1947, more than 40,000 females nested in a single day on one beach in Mexico. Collection of turtle eggs, development of nesting beaches, commercial fisheries by-catch and oil extraction pushed the species to near extinction by the 1970s.

TEXAS

The Kemp's Ridley sea turtle was extirpated from the U.S. as a breeding species by the 1950s, though it continued to forage in U.S. waters along the Gulf Coast and the Atlantic. In 1978, an international, multi-agency project began to reestablish a nesting colony at Padre Island National Seashore in Texas [5]. From 1978 to 1988, 22,507 eggs were transported from Mexico for incubation and imprinting on the sands and surf of the national seashore. Most hatchlings were transported to a National Marine Fisheries Service laboratory where they were raised away from predators for nine to 11 months. They were then released into the Gulf of Mexico, where it was hoped that they would return to nest on the sands where they were imprinted.

The program proved controversial at first, due to setbacks and little nesting success between 1979 and 1994, but nest counts began to increase in 1995, accelerated in 2004, and reached reaching 199 in 2011 [9, 11, 12, 13].

By 2006, 60 percent of Texas nesting occurred in Padre Island National Seashore [1], with the remainder occurring at seven additional sites: Bolivar Peninsula, Galveston Island, near Surfside (Brazoria County), Mustang Island, South Padre Island, Boca Chica Beach, and Aransas/Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuge [1, 10]. Nesting turtles returned to Matagorda Island, Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuge in 2005 (three nests) and continued to nest in 2006 (four nests), and 2007 (four nests) [10].

OTHER STATES

Very small, sporadic nesting efforts occur in Alabama, Florida and South Carolina. In 1999, single nests were found on the Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama and on Gulf Island's National Seashore in Perdido Key, Fla. [3]. In 2001, a single hatchling was found at Bon Secour and a nest was found at Gulf Shores’ West End Beach, Ala. [2, 3].

MEXICO

The vast majority of Kemp’s Ridley turtles nest on a single beach near Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico. The Mexico population declined from more than 40,000 nests in 1947 to 740 in 1985 before steadily climbing to 10,099 in 2005 and at least 11,600 in 2006 [4, 8, 9]. The increase was facilitated by habitat protection, prohibition and education about egg collection, and the requirement that turtle excluder devices be used by U.S. and Mexican shrimp fishing fleets in the Gulf of Mexico. Prior to their use, the fleet killed 500 to 5,000 turtles annually [6].

CITATIONS

[1] Padre Island National Park. 2007. The Kemp's ridley sea turtle. U.S. National Park Service. Website (http://www.nps.gov/pais/naturescience/kridley.htm) accessed August 30, 2007.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. World's Most Endangered Sea Turtle Nest Discovered Along U.S. Coastline for Only Ninth Time This Year, August 17, 2001 press release. (http://www.fws.gov/southeast/news/2001/al01-001.html)

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Availability of an Environmental Assessment and Receipt of an Application for an Incidental Take Permit for FML81A, LLC, Fort Morgan Peninsula, Baldwin County, AL. May 9, 2002 (67 FR 31359).

[4] Turtle Expert Working Group. 2000. Assessment Update for the Kemp’s Ridley and Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations in the Western North Atlantic. U.S. Dep. Commer. NOAA Tech. Mem. NMFS-SEFSC-444, 115 pp.

[5] Arroyo, B., P. Burchfield, L.J. Pena, L. Hodgson, and Pl Luevano. 2003. The Kemp's Ridley: recovery in the making Endangered Species Bulletin, May-June, 2003.

[6] NOA Fisheries. 2005. Kemp's Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) (www.nmfs.noaa.gov/prot_res/species/turtles/kemps.html)

[8] Caribbean Conservation Corporation and Sea Turtle Survival League. 2006. Sea turtle species of the world. Website (www.cccturtle.org/species_world.htm) accessed January 23, 2006.

[9] Hanna, B. 2006. Slow and steady revives the species. Fort Worth Telegram-Star, July 3, 2006. Available at http://www.texansforkay.com/news/Read.aspx?ID=103

[10] Stinson, T. 2007. Personal communication with Tonya Stinson, Environmental Education Specialist, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Complex, May 22, 2007.

[11] National Marine Fisheries Service et al. 2011. Bi-National Recovery Plan for the Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). Silver Spring, MD. 177 pp.

[12] Shaver, D. 2012. Sea Turtle Nesting Season 2011. Padre Island National Park. www.nps.gov/pais/naturescience/nesting2011.htm

[13] Shaver, D. 2011. Kemp's Ridley nests found on Texas coast, 2000-2010. Padre Island National Park.

Lake Erie water snake (off-shore DPS) (Nerodia sipedon insularum)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 8/30/1999 | Recovery plan: 9/19/2003 |

Range: OH

SUMMARY

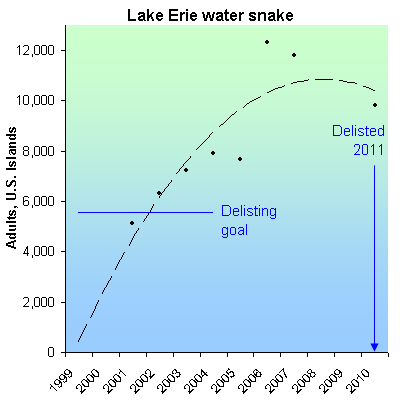

The Lake Erie water snake was listed as threatened in 1999 due to human persecution which had reduced its population size. After listing, public education campaign were carried out which successfully improved public attitudes toward this small, non-venomous snake. Consequently, its population increased from 5,130 in 2001 to 7,670 in 2005 to 9,800 in 2010. It was delisted in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The Lake Erie watersnake is a subspecies of the Northern watersnake (N. sipedon sipedon) which occurs primarily on the offshore islands of western Lake Erie in Ohio and Ontario, Canada, but also on a small portion of the U.S. mainland on the Catawba and Marblehead peninsulas of Ottawa County, Ohio.

It was listed as "threatened" under the Endangered Species Act in 1999 primarily due to population reduction caused by human persecution. After listing, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service undertook a successful outreach campaign that improved public attitudes toward the snake and allowed the population to recover. The population increased from 5,130 snakes in 2001 to 9,800 snakes in 2010 [1, 2].

The 2003 federal recovery plan required a U.S. islands population of over 5,555 adult snakes for a period of six or more consecutive years. The population goal has been met and surveys indicate that public perception of the snake has improved and threats have been largely abated. The species was determined to be recovered and delisted in 2011 [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Removal of the Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 76 FR 50680.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Servcie. 2007. Lake Erie Water Snake: Adult Population 2001 - 2007. Svailable at http://www.fws.gov/midwest/endangered/reptiles/lews/lewspopulation.html.

Pacific green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizi)

| Status: Threatened/Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 7/28/1978 | Recovery plan: 1/12/1998 |

Range: AS(b), CA(s), GU(b), HI(b), MP(b), OR(o), WA(o) ---

SUMMARY

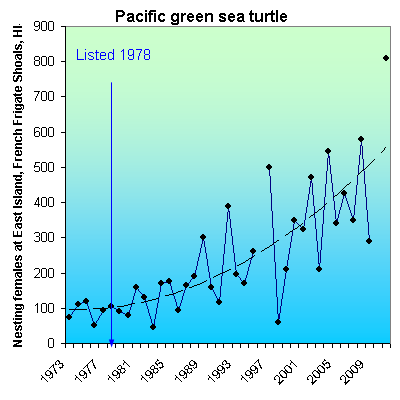

Green sea turtles in the Pacific are threatened by habitat loss, egg collection, hunting, beach development, bycatch mortality in commercial fisheries, and sea level rise due to global warming. Since being protected in 1978, the number of females nesting at East Island of French Frigate Shoals, approximately half of the total Hawaii population, increased from 105 in 1978 to 808 in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and as far north as Massachusetts [1, 5]. It migrates long distances between foraging and nesting areas [5]. Typical near-shore habitats are shallow waters inside bays, reefs and inlets. Most nesting occurs on minimally disturbed open beaches. Females generally reproduce every two or more years, with an average of three to four nests during a breeding year.

U.S. populations occur in the Atlantic from Massachusetts to Texas and the Caribbean, and in the Pacific from the mainland coast to Hawaii, Guam and the Mariana Islands [1, 5]. Nesting populations within the United States have increased in size since the species was protected in 1978.

The taxonomic distinctions between Pacific and East Pacific populations of green sea turtle are under review. It remains unresolved whether C. mydas agassizii qualifies as a separate species or a subspecies of green sea turtle.

HAWAII AND THE FAR PACIFIC

In Hawaii, most nesting occurs at East Island of French Frigate Shoals [2, 6]. Nesting females increased there from 75 in 1973 to 808 in 2011 due to cessation of hunting and protection of habitat [6, 8]. The number of nesting females at East Island represents approximately half of the estimated number of nesting females in all of Hawaii [9].

Other U.S.-associated Pacific Islands that support green sea turtle populations include American Samoa (25-35 nesting females), the Federated States of Micronesia (three atolls, more than 100 nesting females) and Guam (little but regular nesting) [2]. In general, the major threat on urbanized Pacific islands is habitat loss and problems associated with rapidly expanding tourism. In particular, human development is having an increasingly serious impact on green sea turtle nesting beaches. On rural and developing islands, including American Samoa and some islands of the Northern Mariana Islands and Micronesia, human consumption of turtles remains a problem. The relatively recent increase in fibropapillomatosis (a tumorous disease) is a concern [2].

U.S. MAINLAND

The population status and migratory habits of East Pacific green turtles frequenting waters off the U.S. West Coast are unknown, and there are no known nesting sites in the United States [3]. Severe population declines in this population over the past 30 years were due largely to massive overharvesting of wintering turtles in the Sea of Cortez from 1950-1970 and intense collection of eggs between 1960 and early 1980 on mainland beaches of Mexico. The population was thought to be declining as of 1998. A small group (30-50) of resident East Pacific green sea turtles is found in San Diego Bay. Although they do not nest in the United States, this group appears to remain in the area for much of the year because of the warm water effluent from a power-generating station [2]. There is a ban on high-speed boat traffic in the south portion of the bay, but it is rarely enforced and boat strikes may pose a threat [2].

CITATIONS

[1] Plotkin, P.T. (editor). 1995. National Marine Fisheries Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Reviews for Sea Turtles Listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, Maryland.

[2] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[3] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the East Pacific Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Populations of Atlantic Green Turtle. National Marine Fisheries Service, Washington, DC.

[6] Tiwari, M., G.H. Balazs and S. Hargrove. 2010. Estimating carrying capacity at the green turtle nesting beach of East Island, French Frigate Shoals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 419:289–294.

[7] National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 105 pp.

[8] Maison, K.A., I. Kinan Kelly and K.P. Frutchey. 2010. Green Turtle Nesting Sites and Sea Turtle Legislation throughout Oceania. U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-F/SPO-110, 52 pp. http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/tm/110.pdf

[9] Ishizaki, A. 2012. Personal communication. Protected Species Coordinator, Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. May 19, 2012.

Plymouth red-bellied cooter (DPS) (Pseudemys rubriventris pop. 1)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 4/2/1980 | Listed: 4/2/1980 | Recovery plan: 5/6/1994 |

Range: MA(b) ---

SUMMARY

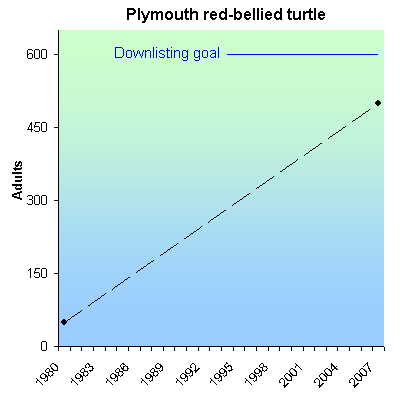

Endemic to ponds in eastern Massachusetts, the Plymouth population of the northern red-bellied cooter is threatened by suburban sprawl, water withdrawals, human recreation, wildfire suppression, predation and environmentally skewed gender ratios. At the time of listing in 1980, there were fewer than 50 turtles in 12 ponds. As of 2007, the population size was estimated to be 400-600 breeding age individuals distributed in 20 ponds.

RECOVERY TREND

The Plymouth Distinct Population Segment of the northern red-bellied cooter (Pseudemys rubriventris) is endemic to ponds in eastern Massachusetts [1]. It formerly occurred in a patchy distribution in most of the state's coastal counties including Essex, Middlesex, Plymouth, Barnstable and Dukes. The only non-coastal county with a historical record is Worcester. Today it occurs only in Plymouth County.

Due to the loss of historic populations, increasing shoreline and between-pond development, and increased predation pressure, the northern red-bellied cooter was placed on the endangered species listed and granted critical habitat in 1980 [1]. Twelve occupied ponds were known at the time. Three additional populations, including Federal Pond, were discovered in subsequent years. Federal Pond was and is the largest population. An active "headstarting" program introduced the cooter to 10 additional ponds and two rivers by 2005 [2, 3, 4]. All nests discovered each year are caged to protect the eggs and hatchlings from predators (about 95 percent of uncaged nests suffer predation) [2]. When hatching is complete, 50 percent of the hatchlings are released into the same pond and 50 percent are moved to headstarting facilities that raise them to a size that is less vulnerable to predation. The headstarted turtles are reintroduced to the same or new sites. Between 1985 and 2006, the program released 2,725 turtles [3, 4, 6]. Headstarted turtles were first documented to breed in the wild in 2000 [5].

Due to the difficulty of censusing the species, quantitative population trend data have not been gathered [2]. However, species experts are in agreement that the number of occupied sites and the number of individuals have increased in size since 1980, primarily due to the headstarting program and to a lesser extent natural reproduction [2, 4]. The 1994 federal recovery plan requires a total of at least 600 breeding-age turtles distributed among at least 15 self-sustaining populations for downlisting to be considered [1]. Delisting will require at least 1,000 breeding-age turtles in 20 or more self-sustaining populations.

At the time of listing in 1980 there were fewer than 50 turtles in 12 ponds. As of 2007, the total population size was estimated to be 400 to 600 breeding-age individuals distributed in 20 ponds. Less than half of the ponds, however, likely contain more than 20 breeding-age turtles. Population estimates are based primarily on estimated high survival rates of known numbers of released headstarted turtles and actual survey data are only available for some sites for the number of wild turtles present in ponds. In 1991, Crooked Pond supported 40 turtles, Island Pond supported 70, Gunners Exchange-Hoyts Pond supported 67 and Federal Pond supported 171. In 2001, 63 turtles were counted at Great South Pond and 31 were counted at Boot Pond [6].

The turtle was listed in 1980, and remains today listed as the subspecies Pseudemys rubriventris ssp. bangsi. That subspecies is no longer recognized. In its 2007 Five-Year Review [6], the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that the taxa should instead be listed as the Plymouth Distinct Population Segment of the northern red-bellied cooter based on genetics, morphology, geographic isolation and use of a habitat unique to the species. The review also reaffirmed the turtle's endangered status, which would be required by a formal reclassification. The Five-Year Review, however, is not a regulatory document and can not in itself carryout the reclassification. Thus the turtle continues to be listed as the invalid subspecies. A delisting petition, challenging the turtle's taxonmy was filed in 2006 by The Wilderness Institute [5], a national anti-endangered species organization associated with former congressman Richard Pombo. The Fish and Wildlife Service issued a positive 90-day finding the same year [8], but has not proceeded since then. Since the reclassifiction will have no conservation effect and The Wilderness Institute no longer exists, the agency has likely not prioritized finishing the taxonomic reclassification.

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Plymouth Redbelly Turtle (Pseudernys rubriventris) Recovery Plan, Second Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildife Service, Hadley, Massachusetts. 48 pp.

[2] Amaral, M. 2006. Personal communication with Michael Amaral, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Concord, NH, February 7, 2006.

[3] Amaral, M. 2006. Released northern red-bellied cooters, 1985-2003. Spreadsheet provided by Michael Amaral, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Concord, NH, February 7, 2006.

[4] French, T. 2006. Personal communication with Tom French, Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Westborough, MA, February 7, 2006, and February 8, 2006.

[5] Gordon, R. 1997. Petition to Remove the 'Plymouth Redbelly Turtle' ('Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi') from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. National Wilderness Institute, February 3, 1997.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Northern Red-bellied Cooter (Pseudemys rubriventris) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. New England Field Office. 39 pp. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc1109.pdf

[7] U.S. Fish and Willdife Service. 1980. Designation of the Plymouth red-bellied turtle as an endangered species. April 2, 1980 (45 FR 21828).

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. 90-day finding on a petition to delist the Plymouth redbelly turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi). October 3, 2006 (45 FR 21828).

Virgin Islands tree boa (Epicrates monensis granti)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 10/13/1970 | Recovery plan: 3/27/1986 |

Range: PR(b), VI(b) ---

SUMMARY

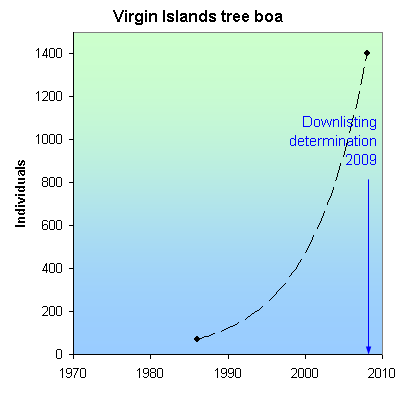

The Virgin Islands tree boa is threatened by habitat destroying development, introduction of predatory mongooses, cats, and rats, and sea level rise. It was listed as endangered in 1970. In 1986, there were 71 snakes in four populations. Wild populations have increased and two new ones have been created. In 2008, 1,400 snakes were known in six populations. In 2009 it was recommended for downlisting.

RECOVERY TREND

The Virgin Islands boa (Epicrates monensis granti), a blotched brown semi-arboreal snake, inhabits subtropical dry forests where it hunts at night, primarily eating sleeping lizards [2]. During the day, it hides in termite nests or under rocks and debris [3].

It's limited historic range extends from Puerto Rico eastward into the British Virgin Islands [1]. In Puerto Rico, it currently inhabits Cayo Diablo, Cayo Ratones, Culebra and Río Grande. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, it is restricted to extreme eastern St. Thomas [2]. The disjunct current distribution indicates a decline from historical levels [2].

When conditions are favorable, this species can exist in high densities on small islands [1]. Large-scale habitat destruction and the introduction of exotic mammalian predators have caused severe population declines [1]. The introduction of the Indian mongoose on St. Thomas, St. John, Tortola and Jost Van Dyke contributed to population declines on these islands [3]. Feral and domestic cats, which prey on adult boas, have become ubiquitous on St. Thomas [1]. Two rat species, also introduced on many islands, are potential predators of young boas [3].

Development on the east end of St. Thomas threatens the remaining boa population there [1]. Currently, the small, uninhabited cays and islets where much of the remaining populations have become concentrated tend to be vulnerable to inundations from the ocean and storms [4].

It was listed as an endangered species in 1970.

A federal recovery plan was developed in 1986 at which time only 71 snakes were known. A Mona/Virgin Islands Boa Species Survival Plan was developed in 1990 [1].

A captive breeding program was initiated by the Toledo Zoological Gardens in 1985, and reintroductions were initiated on Cayo Ratones in 1993 and Stevens Key in 2002 [1, 5, 6]. On the former, 31 reintroduced boas increased to 482 snakes by 2004 [6]. On the latter, 42 introduced snakes increased to 170 by 2007 [5, 6].

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended downlisting the Virgin Islands tree boa in 2009 [6].

CITATIONS

[1] Tolson P.J, and M. A. Garcia. AZA Species Survival Plan Profile Mona/Virgin Islands Boa: A U.S./Puerto Rico Partnership Seeks to Recover Endangered Boa. Accessed at http://www.umich.edu/~esupdate/library/97.01 02/tolson.html

[2] Platenberg, R. J., F. E. Hayes, D. B. McNair, and J. J. Pierce. 2005. A Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Plan for the U.S. Virgin Islands. Division of Fish and Wildlife, St. Thomas. 216 pp.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Species Account, Virgin Islands Tree Boa. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Endangered Species. http://www.fws.gov/endangered/i/c/sac0q.html

[4] American Zoo and Aquarium Association. 1998. Virgin Islands Boa 98 Fact Sheet. Accessed at http://www.nagonline.net/Fact%20Sheet%20pdf/AZA%20-%20Virgin%20Islands%20Boa%20Species%20Survival%20Plan.pdf

[5] Peter J. Tolson. 2006. Personal Communication.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Virgin Islands Tree Boa (Epicrates monensis granti) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Boquerón, Puerto Rico. 25 pp.