American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none |

| Listed: 8/13/1989 | Recovery plan: 9/27/1991 |

Range: AR(b), KS(b), MA(b), NE(b), OH(b), OK(b), RI(b), SD(b), TX(b) --- AL(x), CT(x), DE(x), DC(x), FL(x), GA(x), IL(x), IN(x), IA(x), KY(x), LA(x), ME(x), MD(x), MI(x), MN(x), MS(x), MO(x), MT(x), NH(x), NY(x), NJ(x), NC(x), ND(x), PA(x), SC(x), TN(x), VT(x), VA(x), WV(x), WI(x)

SUMMARY

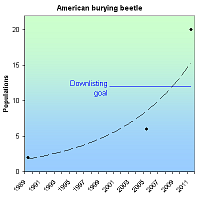

The cause of the American burying beetle's 90% range loss is not well understood, but is thought to be due to disruptions in the food and reproductive web. It is threatened by competition, drought, invasive ants and habatat loss. When listed as endangered in 1989, there were only two known populations. Captive breeding, reintroduction efforts and intensive surveys have increased the total number of populations to 20 or more in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) is a large, spectacularly colored orange and black insect. It formerly occurred across a vast range from Nova Scotia south to Florida, west to Texas, and north to South Dakota. It was documented in 150 counties in 34 states, the District of Columbia, and three Canadian provinces. Total historical numbers are not known, but the species may well have occurred in the tens of millions. The burying beetle's dramatic decline has been called "difficult to imagine" and “one of the most disastrous declines of an insect’s range ever to be recorded” [2]. It was extirpated from mainland New England through New Jersey by the 1920s, from the entire mainland east of the Appalachian Mountains by the 1940s, and from the mainland east of the Mississippi River by 1974. It is absent from about 90 percent of its historic range.

The largest of North America's 32 burying beetles, N. americanus is uniquely dependent upon quail-size carrion weighing 100 to 200 grams [1, 15]. Males smell freshly dead mammals and birds (and occasionally even fish) within an hour of death and up to two miles away. Females arrive shortly thereafter, attracted by male pheromones. A competition ensues and is typically won by the largest male and female. Lying on their backs, the winning couple inches the carrion into an excavated burial chamber. During this time, orange phoretic mites borne by the beetles leap to the carcass, cleaning it of fly eggs and microbes. The buried carcass is relieved of its feathers, feet, tail, ears and/or fur. Now known as a "brood ball," it is coated with oral and anal embalming secretions to retard fungal and bacterial growth. The beetles then mate and within 24 hours lay eggs in the soil near the carcass. White grubs emerge three or four days later and are carried to the carcass. The parents also defend the grubs from predators and feed them regurgitated food. The American burying beetle is one of the few non-colonial insects in the world to practice dual parenting. In approximately a week, the grubs leave the chamber and pupate into adults.

The cause of the American burying beetle's decline is not well understood, but the most cogent hypotheses see it as victim of interacting food chain disturbances which reduced the number of large carcasses [2]. The passenger pigeon, which formerly occurred in the billions, was an ideal size. It was last seen in 1914 and was greatly reduced in number in the decades preceding. Its decline and disappearance occurred just prior to the burying beetle's. Other endangered or greatly reduced carrion of ideal size include the black-footed ferret, northern bobwhite, and greater prairie chicken. Competition for dwindling carrion numbers was exacerbated by increasing numbers of mid-sized predators following the extinction or decline of large predators such as the eastern cougar, mountain lion and gray wolf. In their absence, coyotes, raccoons, fox and other mid-size scavengers increased in number and consumed more quail-size carrion. Finally, as habitats became more fragmented mid-size predators were increasingly able to exploit forest and grassland edges, taking more carrion.

At the time of listing in 1989, two populations were known: one on Block Island, Rhode Island and one in eastern Oklahoma [1]. Since then, populations have been discovered in South Dakota (1995), Nebraska (1992), Kansas (1997), Arkansas (1992) and Texas (2003), as well as additional populations in Oklahoma [3, 23]. The total number of populations has increased to at least 20 as of 2011 [7, 11, 13, 10, 22, 23].

RHODE ISLAND. Located 12 miles off the south coast of Rhode Island, Block Island supports the last natural population of the American burying beetle east of the Mississippi River. The island is free of foxes, raccoons, skunks and coyotes. A study of one-third of the population determined that it was relatively stable between 1991 and 1997 (mean=184), steadily grew to 777 in 2006, and then declined to 80 in 2011 in part because of a reduction in supplementation of carcasses [8]. This population served as the source for the successful Roger Williams Park Zoo captive breeding program initiated in 1994 and for direct translocations to Nantucket and Penikese Island.

MASSACHUSETTS. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Massachusetts shortly after 1940 [1] and was reintroduced to the 70-acre Penikese Island in Buzzards Bay over a four-year period between 1990 and 1993. Reintroduced beetles initially came from a Boston University captive breeding population originating from Block Island stock [6]. The population persisted at low numbers through 2002, but was not located in 2003, 2004 or 2005. On Nantucket, 2,892 beetles were introduced from the Roger Williams Park Zoo between 1994 and 2005 to the Audubon Society’s Sesachacha Heathland Wildlife Sanctuary (east side of the island) and the Nantucket Conservation Foundation’s Sanford Farm (west side of the island) [5, 6, 21]. Existing and new beetles were trapped and provisioned with quail carcasses each summer to boost larva production [5]. The introduction program ended in 2005 in order to determine if population is self-sustaining [6]. The Penikese Island reintroduction effort has been deemed a failure, and the success of the Nantucket effort is unknown, although the population is believed to persist [23].

OHIO. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Ohio shortly after 1974 when it was last seen near Old Man's Cave in Hocking Hills State Park [9, 10]. A short-lived captive population derived from Block Island stock was established in 1991 at the Insectarium of the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden [1]. In July 1998, Ohio became the site of the first mainland introduction when 35 pairs of beetles taken from a wild population near Fort Chaffee, Ark. were introduced to the Waterloo Wildlife Experiment Station in southeast Ohio [10]. The Waterloo population was augmented in 1999 (20 pairs and 15 females) and 2000 (33 pairs and four males), but not 2001 or 2002. Additional augmentation occurred in 2003. A captive population established at Ohio State University in 2002 produced 828 beetles as of 2004; 199 of these were used for reintroductions in 2003 and 156 were reintroduced in 2004. The Wilds (managed by the Columbus Zoo) plans to create a second captive colony [10] and a second reintroduction is planned for the Athens District of the Wayne National Forest [11]. The success of the Ohio reintroduction efforts is unknown but is thought to be limited [23].

MISSOURI. The American burying beetle was extirpated from Missouri in the early 1980s [1]. It has not been relocated despite repeated and recent surveys [12]. A captive breeding population was established at the Monsanto Insectarium, St. Louis Zoo in 2004 (with 10 pairs from Ohio State University) and 2005 (with wild beetles from Arkansas) [7, 15]. Six-hundred-fifty-four adults were produced as of June 2005, 50 of which were transferred to Ohio State University. Plans are being developed to introduce the species to The Nature Conservancy and Missouri Department of Conservation lands. [7].

OKLAHOMA. The presence of American burying beetles has recently been confirmed in 22 eastern Oklahoma counties, reported but unconfirmed in two more, and likely to occur in nine more [16]. The largest known concentrations are a population at Camp Gruber and a smaller one on private timber lands held by Weyerhaeuser International. Captures (not to be confused with population estimates) at Camp Gruber fluctuated around a mean of 213 adults between 1992 and 2003 without discernable trend. Captures at Weyerhaeuser had a mean of 52 adults between 1997 and 2003, but this population collapsed in 2006 and 2007, perhaps due to drought or fire ants [23].

NEBRASKA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Nebraska in 1992 [18]. Between 1995 and 1997, nearly 1,000 individuals were trapped or collected in the upland grasslands and cedar tree savannas of the dissected loess hills south of the Platte River in Dawson, Gosper and Lincoln counties of Nebraska. The population is estimated at about 3,000 adults.

SOUTH DAKOTA. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in South Dakota in 1995 and is believed to have a statewide population in excess of 500 adults [17].

ARKANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Arkansas in 1992 [3]

KANSAS. The American burying beetle was rediscovered in Kansas in 1997 [19].

TEXAS: The American burying beetle, thought to be extirpated from Texas since the 1930s, was rediscovered in 2003 [3]. Two populations are now known to exist, one on a military base, the other on a Nature Conservancy preserve.

The American burying beetle recovery plan states: "The interim objective [extinction avoidance] will be met when the extant eastern and western populations are sufficiently protected and maintained, and when at least two additional self-sustaining populations of 500 or more beetles are established, one in the eastern and one in the western part of the historical range. Reclassification will be considered when (a) 3 populations have been established (or discovered) within each of four geographical areas (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and the Great Lake states), (b) each population contains 500+ adults, (c) each population is self-sustaining for five consecutive years, and, ideally, each primary population contains several satellite populations.”

The beetle remains threatened by the limited availability of carcasses to use for reproduction, by invasive species such as fire ants which compete for carcasses, and by drought and climate change. The Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport tar sands oil from Canada to Texas, is a new threat to the beetle in 2011 and would cut through the core of the beetle's range in South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

CITATION

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) recovery plan. Newton Corner, MA.

[2] Sikes, D.S. 2002. A review of hypotheses of decline of the endangered American burying beetle (Silphidae: Nicrophorus americanus Olivier). Journal of Insect Conservation 6: 103–113

[3] Quinn, M. 2006. American Burying Beetle (ABB). Website (http://www.texasento.net/ABB.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[4] Peyton, M.M. 1997. Notes on the range and population size of the American Burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) in the dissected hills south of the Platte River in central Nebraska. Paper presented at the 1997 Platte River Basin Ecosystem Symposium, Feb. 18-19, 1997 Kearney Holiday Inn Kearney, Nebraska.

[5] Mckenna-Foster, A.A., M.L. Prospero, L. Perrotti, M. Amaral, W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American burying beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction to Nantucket, MA, 2004-2005. Abstract presented at the First Nantucket Biodiversity Initiative Conference, September 24, 2005, Coffin School, Egan Institute of Marine Studies, Nantucket, MA.

[6] Amaral, M. 2005. Personal communication with Michael Amaral, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Concord, NH, November 28, 2005.

[7] Homer, P. 2005. Missouri's Threatened and Endangered Species Accomplishment Report: July 1, 2004 - June 30, 2005. Missouri Department of Conservation.

[8] Raithel, C. 2012. American burying beetle, Southwest Block Island trend, 1991-2011. Spreadsheet provided by Christopher Raithel, Rhode Island Dept of Environmental Management, Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, April 5, 2012.

[9] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2005. American Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus americanus. Website (www.dnr.state.oh.us/wildlife/Resources/projects/beetle/beetle.htm) accessed January 28, 2006.

[10] Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife. 2004-2005 Wildlife Population Status and Hunting Forecast.

[11] Wayne National Forest. 2004. Schedule of Proposed Action, 10-01/04-12/31/04.

[12] Stevens, J. and B. Merz. American Burying Beetle Survey in Missouri. St. Louis Zoo, Department of Invertebrate. Website (http://biology4.wustl.edu/tyson/projectszoo.html) accessed January 29, 2006.

[13] Dabeck, L. 2006. The American Burying Beetle Recovery Program: Saving nature's most efficient and fascinating recyclers. Roger Williams Park Zoo. Website (www.rogerwilliamsparkzoo.org/conservation/burying%20beetle%20program.cfm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[14] Kozol, A. J. 1990. NICROPHORUS AMERICANUS 1989 laboratory population at Boston University: a report prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Unpublished report.

[15] Stevens, J. 2005. Conservation of the American burying beetle. CommuniQue, September, 2005:9-10.

[16] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Website (www.fws.gov/ifw2es/Oklahoma/beetle1.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[17] South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. 2006. The American Burying Beetle in South Dakota. Website (www.sdgfp.info/Wildlife/Diversity/ABB/abb.htm) accessed January 29, 2006.

[18] Peyton, M.M. 2003. Range and population size of the American burying beetle (Coleoptera:Silphidae) in the Dissected Hills of South-central Nebraska. Great Plains Research 13(1): 127-138

[19] Miller, E.J. and L. McDonald. 1997. Rediscovery of Nicrophorus americanus Olivier (Coleoptera Silphidae) in Kansas. The Coleopterists' Bulletin 5(1):22.

[20] Mckenna-Foster, A., W.T. Maple, and R.S. Kennedy. 2005. American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus) survey and reintroduction on Nantucket 2005. Unpublished report.

[21] Perrotti, L. 2006. Roger Williams Park Zoo American Burying Beetle Project Statistics. Spreadsheet provided by Lou Perrotti, American Burying Beetle project coordinator, Roger Williams Park Zoo, Providence, RI, February, 2006.

[22] NatureServe. 2011. American Burying Beetle Species Profile. Available at: http://www.natureserve.org

[23] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. American Burying Beetle (Nicropherus americanus) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation. 53 pp.

American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: 8/11/1977 |

| Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(b), AR(m), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(m), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(m), KY(b), LA(m), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(m), MO(m), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(m), OH(b), OK(m), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(m), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

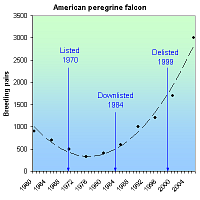

The use of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides thinned American peregrine falcon eggshells, causing reproductive failure and population declines. The banning of DDT, captive-breeding efforts and nest protections allowed falcons to increase from 324 breeding pairs in 1975 to 3,005 pairs as of 2006. The species was delisted in 1999.

RECOVERY TREND

The American peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) breeds only in North and Central America and occurs throughout much of North America from the subarctic boreal forests of Alaska and Canada south to Mexico [1]. It is estimated that prior to the 1940s, there were approximately 3,875 nesting pairs of peregrines in North America [1]. From the 1940s through the 1960s, however, the population of the peregrine, and many other raptors, crashed as a result of the introduction of synthetic organochlorine pesticides to the environment. By 1975, there were only 324 known nesting pairs of American peregrine falcons in the U.S. [2].

Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [1]. Organochlorine pesticides were put into use following World War II. Use peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s and continued through the early 1970s [1]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey because they ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches [1]. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. During the period of DDT use in North America, eggshell thinning and nesting failures were widespread in peregrine falcons, and in some areas, successful reproduction virtually ceased [1].

The degree of exposure to these pesticides varied among regions, and peregrine falcon numbers in more contaminated areas suffered greater declines [1]. The eastern population plunged from an estimated 350 active nest sites in the 1930s and 1940s to no active breeding birds from 1964 to 1975 [3]. Peregrine falcons in the Great Plains states east of the Rocky Mountains and south of U.S. and Canadian boreal forests were also essentially extirpated [1]. West of the 100th meridian, peregrine falcons were significantly reduced [1]. Local populations were greatly depressed or extirpated and by 1965 fewer than 20 pairs were known west of the U.S. Great Plains [1].

In 1970, the American peregrine was listed as endangered and efforts to recover the species began. The use of DDT was banned in Canada in 1970 and in the United States in 1972 [1]. This was the single-most significant action in the recovery of the peregrine falcon [1]. In addition, in the eastern United States, efforts were made to reestablish peregrine falcons by releasing offspring from a variety of wild stocks that were held in captivity by falconers [1]. The first experimental releases of captive-produced young occurred in 1974 and 1975 in the eastern United States [1]. These and future releases demonstrated that “hacking,” the practice of retaining and feeding young captive bred birds in partial captivity until they are able to fend for themselves, was an effective method of introducing captive-bred peregrines to the wild [1]. Since then, more than 6,000 falcons have been released in North America [1]. Approximately 3,400 peregrines were released in parts of southwest Canada, the northern Rocky Mountain States, and the Pacific Coast states [1].

In the late 1970s, Alaska became the first place American peregrine falcon population growth was documented and, by 1980, populations began to grow in other areas [1]. Not only did the number of peregrine falcons begin to increase, productivity (another important measure of population health) improved [1]. Efforts to reestablish peregrine falcons in the East and Midwest proved largely successful, leading to downlisting of the species in 1984 [1], and by 1999 peregrines were found to be nesting in all states within their historical range east of the 100th meridian, except for Rhode Island, West Virginia and Arkansas [1]. In highly urban areas, peregrine falcons showed great adaptability, and began substituting skyscrapers for natural cliff faces as nesting sites [4]. By 1998, the total known breeding population of peregrine falcons was 1,650 pairs in the United States and Canada, far exceeding the recovery goal of 456 pairs. Other recovery goals, including estimates of productivity, egg-shell thickness, and contaminants levels, had also been met, allowing the species to be delisted in 1999 [1]. Monitoring of American peregrine populations has continued under a post-delisitng monitoring plan [5]. The estimated North American population was 3,005 pairs as of 2006 [6].

ALASKA: Surveys conducted between 1966 and 1998 along the upper Yukon River demonstrated increases in the number of occupied nesting territories from a low of 11 known pairs in 1973 to 46 pairs in 1998 [1]. Similarly, along the upper Tanana River, the number of occupied nesting territories increased from two in 1975 to 33 in 1998 [1]. The recovery objective of 28 occupied nesting territories in the two study areas was first achieved in 1988, with 23 nesting territories on the Yukon River and 12 on the Tanana River [1].

PACIFIC STATES: By 1976, no American peregrine falcons were found at 14 historical nest sites in Washington [1]. Oregon had also lost most of its peregrine falcons and only one or two pairs remained on the California coast [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 to 1998 indicated a steadily increasing number of American peregrine falcon pairs breeding in Washington, Oregon and Nevada [1]. Known pairs in Washington increased from 17 to 45 and in Oregon from 23 to 51 [1]. The number of American peregrine falcons in California increased from an estimated low of five to 10 breeding pairs in the early 1970s to a minimum of 167 occupied sites in 1998 [1]. The increase in California was concurrent with the restriction of DDT and included the release of more than 750 American peregrine falcons through 1997 [1].

ROCKY MOUNTAINS/SOUTHWEST: The Rocky Mountain/Southwest population of the American peregrine falcon has made a profound comeback since the late 1970s when surveys showed no occupied nest sites in Idaho, Montana or Wyoming and only a few pairs in Colorado, New Mexico and the Colorado Plateau, including parts of southern Utah and Arizona [1]. Surveys conducted from 1991 through 1998 indicated that the number of American peregrine falcon pairs in the Rocky Mountain/Southwest area has steadily increased [1]. In 1991, there were 367 known pairs; in 1998 the number of pairs increased to 535 [1].

EASTERN STATES: The eastern peregrine population has a unique history and complex status under the Act [1]. Peregrine falcons were extirpated in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada by the mid-1960s [1]. Releases of young captive bred peregrines have reestablished populations throughout much of their former range in the East [1]. In 1998, 193 pairs were counted in five designated eastern state recovery units [1]. The number of territorial pairs recorded in the eastern peregrine falcon recovery area increased an average of 10 percent annually between 1992 and 1998 [1]. Equally important, the productivity of these pairs during the same seven-year period averaged 1.5 young per pair, demonstrating sustained successful nesting [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Final Rule to Remove the American Peregrine Falcon from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, and to Remove the Similarity of Appearance Provision for Free-Flying Peregrines in the Conterminous United States. Federal Register (64 FR 46542).

[2] Hoffman, C. 1999. The Peregrine Falcon is Back! New release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, August 20, 1999.

[3] Clark, K. 2005. The Peregrine Falcon in New Jersey, Report for 2005. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program.

[4] New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. Fact sheet, Peregrine Falcon Falco pereginus. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program. Website <http://www.njfishandwildlife.com/tandespp.htm> accessed February, 2006.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Monitoring Plan for the American Peregrine Falcon, A Species Recovered Under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Endangered Species and Migratory Birds and State Programs. Pacific Region, Portland Oregon 53pp.

[6] Green, M., T. Swem, M. Morin, R. Mesta, M. Klee, K. Hollar, R. Hazelwood, P. Delphey, R. Currie, and M. Aramal. 2006. Monitoring Results for Breeding American Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus anatum), 2003. Biological Technical Publication BTP-R1005-2006. U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius)

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 6/2/1970 | Recovery plan: 6/30/1991 |

Range: AL(m), AK(b), AZ(m), AR(m), CA(m), CO(m), CT(m), DE(m), DC(m), FL(m), GA(m), ID(m), IL(m), IN(m), IA(m), KS(m), KY(m), LA(m), ME(m), MD(m), MA(m), MI(m), MN(m), MS(m), MO(m), MT(m), NE(m), NV(m), NH(m), NY(m), NM(m), NJ(m), NC(m), ND(m), OH(m), OK(m), OR(m), PA(m), RI(m), SC(m), SD(m), TN(m), TX(m), UT(m), VT(m), VA(m), WA(m), WV(m), WI(m), WY(m) ---

SUMMARY

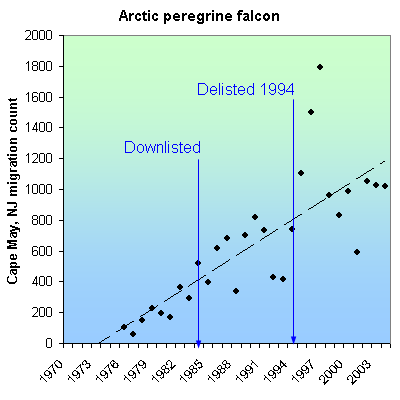

The Arctic peregrine falcon declined due to the egg shell-thinning effects of DDT and other organochlorine pesticides. Its listing as an endangered species in 1970 (along with other birds of prey) prompted the EPA to ban DDT in 1972. Counts of migratory Arctic falcons increased from 103 in 1976, to 1,017 in 2004. The species was downlisted to threatened in 1984 and delisted in 1991.

RECOVERY TREND

The Arctic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius) is one of three peregrine falcon subspecies [1]. It nests in tundra regions of Alaska, Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Quebec, and possibly Labrador), and the ice-free perimeter of Greenland [1]. It is a long-distance migrant that winters in Latin America from Cuba and Mexico south through Central and South America [1].

Severe declines in peregrine falcon numbers began in the 1950s [1]. These declines were linked to organochlorine pesticides that were put into use following World War II, and whose use peaked in the late 1950s-early 1960s [1]. Scientists investigating the peregrine's decline found unusually high concentrations of the pesticide DDT and its breakdown product DDE in peregrine falcons and other birds of prey [2]. Organochlorine pesticides cause direct mortality and reduced reproduction in birds of prey which, being at the top of the food chain, ingest high doses of pesticides concentrated and stored in the fatty tissue of prey animals that themselves ingested contaminated food [1]. Heavily contaminated females may fail to lay eggs and organochlorines passed from the female to the egg can kill the embryo before it hatches. DDE, the principal metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, causing eggs to frequently break before hatching [1]. Arctic peregrine numbers reached their lowest levels in the early 1970s and in some areas of North America successful reproduction virtually ceased [1]. Populations are thought to have decreased by as much as 80 percent [2].

The listing of the Arctic peregrine falcon as endangered in 1970--as well as the bald eagle, brown pelican, and American peregrine falcon shortly before--fostered a national outcry against the production and spaying of DDT. In 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency banned most used of DDT in the United States [1]. Canada had already restricted DDT use in 1970. These restrictions are the central cause of the recovery of the Arctic and American peregrine falcons (the bald eagle and brown pelican benefited greatly as well, but their recovery also involved substantial habitat protections and reintroductions).

As DDT levels declined after 1972, peregrine falcon productivity rates rose to pre-DDT levels and the population size and range began to increase. This happened most rapidly in northern areas, where pesticide exposur was lower and impacts upon populations were less severe [1]. In 1984, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service downlisted the Arctic peregrine falcon from endangered to threatened status [2, 6]. In 1991, the agency initiated a review determine if the species had recovered [2] and in 1994 removed it from the endangered species list [6].

Four major factors were considered in the delisting process: (1) Population size and trend, (2) reproductive performance, (3) pesticide residues in eggs, and (4) eggshell thickness [1]. Despite a lack of long-term studies using consistent methodologies, there was strong evidence of significant population increases throughout the Arctic [1]. Four areas in northern North America (one in Alaska and three in Canada’s North West Territories) for which historical survey information was available indicated the number of Arctic peregrine pairs occupying nesting territories increased since the 1960s [1]. Some areas of Alaska even exceeded the original estimates of pre-DDT-era population size [1]. In addition, in the eastern Arctic, peregrines began nesting in previously vacant nesting sites [1]. Standardized yearly migration counts at New Jersey’s Cape May, an area where Arctic peregrines concentrate during migration, also saw increasing numbers, most likely from Arctic breeding grounds especially in Greenland and eastern Canada (these counts may have also contained peregrines in the American subspecies; however, banding recoveries indicate that the majority of peregrines along the East Coast during fall migration are from the Arctic and thus represent a true increase in Arctic peregrine numbers) [1].

Productivity in all regions where data had been gathered was sufficient to support a stable or increasing population since the 1980s [1]. There had also been improvements in levels of DDE concentration in eggs. Concentrations in excess of 15-20 parts per million (wet weight basis) are associated with high rates of nesting failure. Residue in eggs in 1993 was well below this critical level [1]. Alaskan eggshells collected between 1988 to 1991 were on average only 12 percent thinner than pre-DDT thickness (17 percent or greater reduction in thickness results in population declines).

Arctic peregrine falcon numbers have continued to rise after the species' delisting. On the Sagavanirktok River in Alaska, where Arctic peregrine surveys have been conducted since the late 1950s, the number of pairs increased from five in 1958, to 23 in 1992, to 25 in 1999 [3]. Migration counts at the Cape May Hawkwatch site in New Jersey increased from 103 in 1976 to 1,024 in 2003 [4].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Proposal to Remove the Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 58 Fed. Reg 188.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Peregrine falcon, (Falco peregrinus anatum, Falco peregrinus tundrius, Falco peregrinus pealei). Species account. Website <http://www.fws.gov/species/species_accounts/bio_pere.html> accessed October, 2005.

[3] Wright, J.M. and P.J. Bente. 1999. Documentation of active peregrine falcon nest sites, 1 Oct 1994- 31 March 1998. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Annual research report. Endangered species conservation fund federal aid project SE-2-9, 10, and 11. Juneau, AK. 15 pp.

[4] Cape May Bird Observatory. 2012. Cape May Hawkwatch, Cape May, New Jersey. New Jersey Audubon Society. Website <http://www.njaudubon.org/Sightings/cmhw25.html> accessed April 2, 2012.

[5] NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe’s Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Removal of Arctic Peregrine Falcon From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 59 Fed. Reg. 50796.

Bald eagle (continental U.S. DPS) (Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Continental U.S. DPS))

| Status: Delisted | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: AL(b), AZ(b), AR(b), CA(b), CO(b), CT(b), DE(b), DC(b), FL(b), GA(b), ID(b), IL(b), IN(b), IA(b), KS(b), KY(b), LA(b), ME(b), MD(b), MA(b), MI(b), MN(b), MS(b), MO(b), MT(b), NE(b), NV(b), NH(b), NY(b), NM(b), NJ(b), NC(b), ND(b), OH(b), OK(b), OR(b), PA(b), RI(b), SC(b), SD(b), TN(b), TX(b), UT(b), VT(b), VA(b), WA(b), WV(b), WI(b), WY(b) ---

SUMMARY

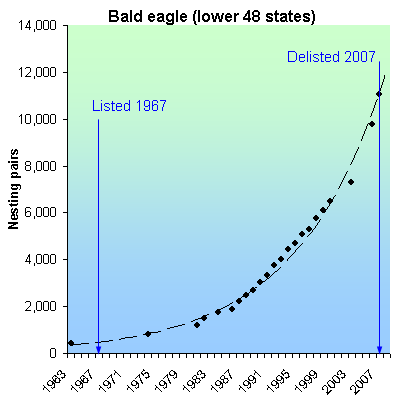

The bald eagle declined throughout the lower 48 states, and was extirpate from most of them due to habitat loss, persecution, and DDT-related eggshell thinning. The banning of DDT, increased wetland protection and restoration, and an aggressive, mostly state-based reintroduction program caused eagle pairs to soar from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when the eagle was removed from the endangered list.

RECOVERY TREND

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) first declined in the 1800s at the hands of trophy hunters, feather collectors, and wanton killing [1]. It was already extirpated or at low numbers in most states by the 1940s when DDT and other organochlorines became widely used. DDE, a breakdown product of DDT, accumulates in the fatty tissue of female eagles, impairing the formation of calcium needed for normal egg formation, causing a decline in reproductive success. DDT caused eagle numbers plummet further, and in 1967 the species was listed as endangered in the lower 48 states [1].

The eagle was joined on the list by the American peregrine falcon, Arctic peregrine falcon and brown pelican in 1970. The listing of these large, charismatic birds rallied the nation to band the production and sale of DDT in 1972.

Due to the DDT ban, increased habitat protection, and aggressive captive breeding and translocation programs (mostly run by state wildlife agencies), bald eagle pairs in the lower 48 soared from 416 in 1963 to 11,052 in 2007 when it was removed from the threatened species list [2, 7]. In 1984, 13 states lacked nesting eagles. By 1998, it was absent from only two. By 2006, it nested in all 48 states [7].

The eagle was proposed for delisting in 1998 [1] and again in 2006 [4]. It was downlisted in 1995 and delisted in 2007 [6].

The bald eagle is managed under five federal recovery plans, divided by region:

Chesapeake Recovery Region: Virginia east of Blue Ridge Mountains, Delaware, Maryland, the eastern half of Pennsylvania, West Virginia Panhandle and two-thirds of New Jersey. Delisting goals were met in 1996 [1]. As of 2003, there were more than 800 nesting pairs in this region [4].

Northern States Recovery Region: 25 Northernmost states. Delisting goals were met in 1991, with 1,349 occupied breeding areas across 20 states. As of 2007, there were an estimated 4,215 breeding pairs in the northern recovery region [6].

Pacific Recovery Region: Idaho, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Montana and Wyoming. Numeric delisting goals were met in 1995 [1]. As of 2001, there were

1,627 nesting pairs in this recovery region [4].

Southeastern Recovery Region: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and eastern Texas. Downlisting goals were met between 1991 and 1998. More than 1,700 pairs were counted in 2000 [4, 6].

Southwestern Recovery Region: Oklahoma and Texas west of the 100th meridian, New Mexico, Arizona and California bordering the Lower Colorado River. The goal established in the recovery plan has been exceeded. In 2003, 46 occupied breeding areas were reported in New Mexico and Arizona. In 2004, the Arizona had 41 occupied breeding areas [4].

In the eight Northeast states from New Jersey to Maine and Vermont, nesting eagle pairs increased from 21 in 1967 to 562 in 2005 [5]. The majority were in Maine, which supported all 21 pairs in 1967 and 385 pairs in 2005. Eagles returned to Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1990, with the former supporting 19 pairs in 2005 and the latter eight in 2004. In 2005 there were 53 pairs in New Jersey, 94 in New York and one in Vermont. The Northeast is also an important wintering area, with the Connecticut population increasing from 20 to 92 between 1979 and 2005, and the New York population increasing from six to 194 between 1978 and 2006 [5].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Proposed rule to remove the bald eagle in the Lower 48 states from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Federal Register, July 6, 1999 (64 FR 36453)

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Bald Eagle Numbers Soaring. May 14, 2007 press release.

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Removing the bald eagle in the Lower 48 States from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife; reopening of public comment period with new information. Federal Regiter, February 16, 2006 (71 FR 8238).

[5] Center for Biological Diversity. 2006. Bald eagle trends in the Northeastern United States. Tucson, AZ.

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Removing the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Final Rule. 72 Fed. Reg 37346.

[7] Suckling, K. and W. Hodges. Status of the bald eagle in the lower 48 states and the District of Columbia: 1963-2007. Center for Biological Diversity, Tucson, AZ. Available at http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/bald_eagle/report/index.html.

Black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 8/8/1988 |

Range: AZ(b), CO(b), MT(b), SD(b), UT(b), WY(b) --- KS(x), NE(x), NM(x), ND(x), OK(x), TX(x)

SUMMARY

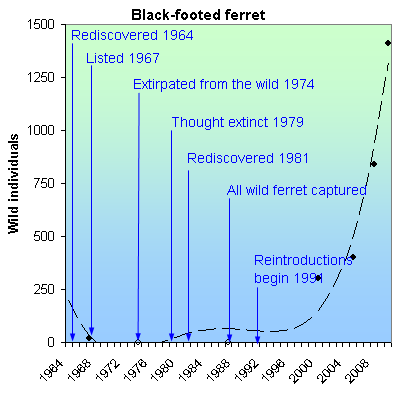

The black-footed ferret was nearly driven extinct due to the elimination of prairie dog colonies by habitat destruction, shooting and plague. It was thought extinct until 1964, extirpated from the wild in 1974, thought extinct again in 1979, then rediscovered in 1981. All ferrets were captured in 1987. A reintroduction program increased wild ferrets from 0 in 1991 to about 1,410 in 2010.

RECOVERY TREND

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), which once occurred throughout the grasslands and basins of interior North America, from southern Canada to Texas, is entirely dependent upon prairie dog colonies [1]. It lives in prairie dog burrows and hunts prairie dogs for food. Its historical range is nearly identical to that of three prairie dog species-- the black-tailed prairie dog, Gunnison's prairie dog and white-tailed prairie dog.

Prairie dogs were formerly abundant and may have supported as many as 5.6 million black-footed ferrets in the late 1800s [2]. They declined precipitously due to conversion of grasslands to agriculture and development, killing for sport, and large-scale poisoning to eliminate reduction in livestock and agriculture industry profits. Prairie dogs are now absent from an estimated 90 to 95 percent of their historically occupied area.

Ferrets declined in parallel to prairie dogs [1]. Of the approximately 130 counties and provinces where ferrets were found since 1880, only 10 were known to have ferrets by the 1960s [1]. In 1971, six ferrets were caught and removed from a declining population in South Dakota in a first effort at captive breeding. The effort was unsuccessful and the last captive ferret died in 1979. Following this loss, the black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct throughout North America.

In 1981 a tiny, relic population was discovered in a prairie dog colony near Meeteetse, Wyoming [1]. The population declined, so to avert the ferret's extinction, all remaining animals were brought into captivity in 1987. These ferrets are the founders of all subsequent reintroductions.

As of 2008, ferrets had been reintroduced to 18 sites [2]. There were 838 wild ferrets and 422 wild adults which is 28 percent of the recovery plan's goal of 1,500 adult ferrets [2]. In early 2010, the Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that it had reached 47 percent of the goal, which would put the adult population at about 705 and the total population at about 1,410 [3].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Black-footed Ferret Recovery plan. Denver, Co. 154pp. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plans/1988/880808.pdf

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Black-footed ferret 5-Year review, summary and evaluation. Pierre, S.D. 38 pp. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2364.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Black-Footed ferret. Website http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/blackfootedferret. Accessed May 10, 2012.

[4] Matchett, R. 2006. Personal communication with Randy Matchett, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Senior Biologist, Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, April 16, 2006.

Gray wolf (Northern Rockies DPS) (Canis lupus (Northern Rockies DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 8/3/1987 |

Range: ID(b), MT(b), eastern OR(b), eastern WA(b), WY(b), northern UT(o)

SUMMARY

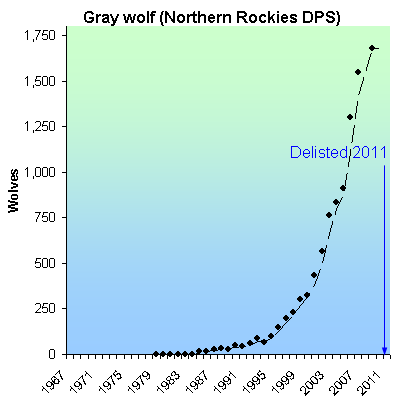

Gray wolves were purposefully hunted, trapped and poisoned to near extinction in the western United States, often by the federal government or with the encouragement of private and state bounties. By 1973, no wild wolves remained in the region. They were listed as endangered in 1967 and began recolonizing the Northern Rocky Mountains from Canada in the early 1980s. Due to prohibition of killing, habitat protection, and reintroductions, the population grew rapidly, was downlisted in 2003, reached 1,679 wolves by 2009, and was delisted in 2011.

RECOVERY TREND

The Northern Rocky Mountains gray wolf (Canis lupus pop.) historically occurred throughout Idaho, the eastern third of Washington and Oregon, all but the northeastern third of Montana, the northern two-thirds of Wyoming, and the Black Hills of South Dakota [1]. As early American settlers began moving west, populations of the gray wolf’s important prey species were over-hunted, causing the wolves to resort to hunting sheep and cattle. As a result, bounty hunting of wolves began in the 19th century and continued through as late as 1965. Around the turn of the century some population control measures were attempted in Yellowstone National Park that led to increased numbers of gray wolves in the area. In response, however, people began killing large numbers of wolves [1]. Beginning in 1912 a minimum of 136 wolves and 80 pups were killed each year and by 1920, only 30 to 40 wolves persisted in this area [1]. By 1973, gray wolves were exterminated from the western lower 48 states and existed only in northeastern Minnesota and Isle Royal, Mich. [2].

Protection of gray wolves was not initiated until the enactment of the Endangered Species Act. By this time gray wolves no longer occurred in the western United States except for the occasional dispersion of Canadian animals into Montana and Idaho that failed to survive long enough to reproduce [3]. Successful recolonization of gray wolves into the Rocky Mountain region did not occur until the early 1980s. Around this time, the Rocky Mountain Gray Wolf Recovery Team was organized with the intent of developing standard observation methods for studying and monitoring the wolves. In 1987, a recovery plan was published. Around this time, the status of the Rocky Mountain Gray wolf was still quite precarious. In Montana, from 1985 to 1986 roughly 15 to 20 wolves were believed to occur near Glacier National Park. In Wyoming from 1982 to 1985, 15 wolves were reported at Yellowstone National Park, and the same number were believed to occur in Idaho in 1986 [1].

Regular monitoring of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf population did not occur until 1995, at which time there were an estimated 14 wolves in Montana and 15 in greater Yellowstone. By 2000, there were an estimated 65 wolves in Montana, 118 in Yellowstone, and 141 in central Idaho [4]. In 2004, a recovery update of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf was released, providing information regarding the status of the gray wolf at three designated recovery areas: the Northwestern Montana Recovery Area (NWMT) in Montana and the Northern Idaho panhandle; the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA), which includes Wyoming and adjacent parts of Idaho and Montana; and the Central Idaho (CID) area covering central Idaho and adjacent parts of southwest Montana. As of 2004, 16 packs containing 59 wolves were documented at NWMT [3]. In the GYA, 171 wolves in 16 packs inhabited the Wyoming portion and 17 packs occurred in the Montana region. In the CID 64 wolves in 40 groups and as individuals were monitored [3]. The total population of free ranging Rocky Mountain Gray wolves for 2004 was estimated at 59 in Montana, 324 in Greater Yellowstone, and 422 in Central Idaho. In 2005 population estimates were 93, 294, and 525 respectively [4]. In 2009 the population of wolves in the Northern Rockies was about 1,679, up from 1,545 in 2007 and 1,300 in 2006 [4].

The U.S. Fish and Wildife Service delisted the Northern Rockies gray wolf in 2008, but the decision was objected to by conservationists who argued that the recovery plan goal was outdated, and insufficient to remove the threat of extinction because it did not require a large enough or well-connected enough wolf meta-population. In 2011, with encouragement from the Department of Interior, Congress for the first time in the history of the Endangered Species Act, overruled the courts and order the delisting of the Northern Rockies gray wolf without biological or legal review [7].

CITATIONS

[1] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1987. Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Denver, CO. 119pp

[2] U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Gray Wolf. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Revised May, 2004.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nez Perce Tribe, National Park Service, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Idaho Fish and Game, and USDA Wildlife Services. 2005. Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Helena, MT. 72pp. Available at <http://westerngraywolf.fws.gov/annualreports.htm>

[4] International Wolf Center. 2011. Gray Wolf Population Trends in the Contiguous United States. Website <http://www.wolf.org/wolves/learn/wow/regions/United_States_Subpages/Biology1.asp> Accessed October 6, 2011..

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Designating the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment; Removing the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment of Gray Wolf From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, February 8, 2006 (71 FR 6634-6660).

[6] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data cited by Brad Knickerbocker, Gray wolves may lose US protected status, Christian Science Monitor, Febraury 1, 2007.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Reissuance of Final Rule To Identify the Northern Rocky Mountain Population of Gray Wolf as a Distinct Population Segment and To Revise the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. 76 Fed. Reg. 26086.

Gray wolf (Southwest DPS) (Canis lupus (Southwest DPS))

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 4/28/1976 | Recovery plan: 9/15/1982 |

Range: AZ(b), NM(b) --- CO(x), OK(x), TX(x), UT(x)

SUMMARY

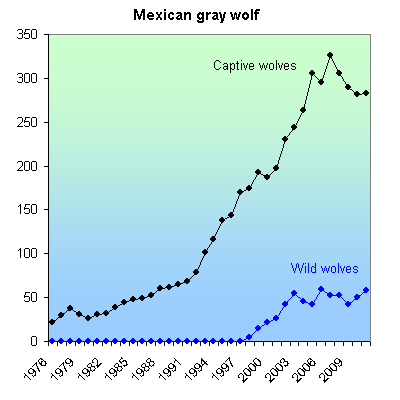

Hunting and trapping resulted in the extirpation of Mexican gray wolves from the United States by 1970. Wolves captured in Mexico were used to establish a captive-breeding program and as of 2010, there were about 50 Mexican gray wolves in the wild.

RECOVERY TREND

The southwestern gray wolf's (Canis lupus) range includes the entire range of the Mexican gray wolf (C. l. baileyi; southern New Mexico, southern Arizona, western Texas and northern Mexico) as well as northern Arizona, northern New Mexico, southern Utah and southern Colorado -- areas historically occupied by other gray wolf subspecies [1]. The wolf was purposefully hunted to near extinction in the Southwest in order to eliminate livestock depredation. In 1970, the last Mexican gray wolf was shot in Texas and the subspecies was extirpated from the United States. At that time, no wolves were present in what is now delineated as the range of the southwestern population.

The Mexican gray wolf was placed on the endangered species list in 1976 and the last five wild wolves from Mexico were captured and moved to captive breeding facilities in the United States and Mexico between 1977 and 1980 [2]. A federal recovery plan was developed in 1982 [3]. By the late 1980s captive breeding facilities were successfully rearing Mexican gray wolves, but none had been reintroduced to the wild. Conservationists filed suit in 1990, obtaining a settlement requiring reintroduction [4]. On March 29, 1998 the first 11 captive Mexican gray wolves were released into the Blue Range of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona near the New Mexico border. By Dec. 31, 2005, there were 35 to49 wild wolves in eight packs on the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest and White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona, and in the adjacent Gila National Forest in New Mexico [5]. The total population of wild and captive wolves grew from 22 in 1976 to 309 in 2004 [6, 7]. In 2010, the total number of captive and wild wolves was 333 [8,9]. Captive breeding is actively curtailed because of constraints on pen space and the failure of FWS to continue efforts to release new wolves into the wild [9].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Final Rule To Reclassify and Remove the Gray Wolf From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife in Portions of the Conterminous United States; Establishment of Two Special Regulations for Threatened Gray Wolves. April 1, 2003 (68 FR 15804).

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1998. Establishment of a Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Gray Wolf in Arizona and New Mexico. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. January 12, 1998 (63 FR 1752).

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, NM.

[4] Wolf Action Group v. Lujan, No. 90-0390 HB (DNM filed Apr. 3, 1990) [5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Gray Wolf Populations in the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Midwest Region. Accessed 1/18/06.

[6] Siminski, P. 2005. Census Report as of 31/12/2004. Email from Peter Siminski, Director of Collections, Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, August 10, 2005

[7] Robinson, M. 2005. Wild Mexican gray wolves in the U.S. and Mexico, 1920-2005. Email from Michael Robinson, Center for Biological Diversity, August 1, 2005.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildife Service. 2011. Mexican Wolf Blue Range Reintroduction Project Statistics. www.fws.gov/southwest/es/mexicanwolf/pdf/MW_popestimate.pdf

[9] Michael Robinson. 2011. Personal Communication, Captive Mexican Wolves in the United States.

Grizzly bear (Yellowstone DPS) (Ursus arctos (Yellowstone DPS))

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: none | Listed: 7/28/1975 | Recovery plan: 3/13/2007 |

Range: MT(b), WY(b)

SUMMARY

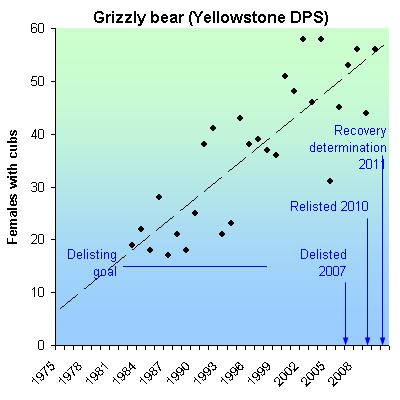

Grizzly bears were extirpated from most of the Lower 48 states by killing, habitat destruction, food chain disruption, and the loss of large wildland areas. By 1975, only six populations remained. Due to Endangered Species Act protections, the Yellowstone grizzly bear population increased from ~224 bears in 1975 to ~582 in 2010. It was delisted in 2007, relisted in 2010 due to concerns about habitat loss and global warming, and declared recovered in 2011 by a federal status report.

RECOVERY TREND

The grizzly bear (Ursus horribilis) formerly ranged over much of North America from the mid-plains westward to California and from central Mexico north to Canada and Alaska [1]. During the early 1880s there were approximately 50,000 grizzlies in the lower 48 states [1]. Between 1850 and 1920, the species was extirpated from 95 percent of its continental U.S. range [2]. In 1922, 37 populations remained [3], declining to six by 1975 when the grizzly bear was listed as “threatened” under the federal Endangered Species Act in the conterminous U.S. [3]. At the time of listing, fewer than 1,000 grizzlies remained in about 2 percent of the species' historic range [1].

Early declines in grizzly populations were largely a result of persecution by European settlers; grizzly bears were shot, poisoned, and trapped wherever they were found [11]. Despite protection under the Endangered Species Act, human-caused mortality, largely resulting from human bear conflicts, has remained the biggest threat to grizzlies [1]. Approximately 88 percent of U.S. grizzly bear deaths documented during studies over the past 20 years were caused by humans, both legally and illegally [2]. Habitat degradation associated with rural or recreational development, road building, and energy and mineral exploration is also a major threat to grizzly bear survival [5]. Habitat destruction in valley bottoms and riparian areas is particularly harmful [5].

The 2005 population was between 1,200 and 1,400 grizzly bears in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and Washington state [1, 3]. Grizzly bears have also been reported in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado in recent years, but have not been confirmed since a grizzly was killed in 1979 [3]. Only two populations (Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide) contain more than 350 individuals [6]. There are six grizzly bear recovery areas in the conterminous U.S. including Yellowstone National Park and surrounding areas.

The Yellowstone recovery area consists of 9,200 square miles of northwest Wyoming, eastern Idaho and southwest Montana [3]. When the grizzly bear was listed in 1975, the population was variously estimated at 136, 229, 234 and 312 bears [11]. Prior to the mid-1980s, low adult female survival was thought to be driving the decline of this population [11]. In the early 1980s, with the development of the first Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan, agencies began work to control mortality and to increase adult female survivorship [11]. In 1999, the population was estimated to have increased to between 400 and 600 [7]. Some research suggests that population trends seen through the mid-1990s were largely tied to the success/failure of the whitebark pine (an important food source) crop [8]. Starting in 1993, counts of female bears with cubs-of-the-year were used to calculate minimum grizzly bear population estimates [6]. These estimates suggest that the grizzly population increased at a rate of 4 percent to 7 percent per year starting in the early 1990s [9]. The 2005 population was estimated at "over 580" bears [9] then re-estimated at "over 500" bears [11]. The Yellowstone population has expanded by 48 percent since 1970, [9] and 68 percent of suitable habitat outside of the recovery zone is now thought to be occupied by grizzly bears [11]. In 2006, the minimum population was 405 [13], and by 2010, Fish and Wildlife Service estimated 582 bears in this population [12].

The 1993 grizzly bear recovery plan outlined three demographic recovery criteria to be met in order to consider delisting of the Yellowstone grizzly: 1) A minimum of 15 females with cubs-of-the-year be maintained over a running six-year average both inside the recovery zone and within a 10-square-mile area immediately surrounding the recovery zone 2) 16 of 18 bear management units within the recovery zone must be occupied by females with young, with no two adjacent bear management units unoccupied, during a six-year sum of observations 3) The running six-year average for total known, human-caused mortality should not exceed 4 percent of the minimum population estimate in any two consecutive years; and human-caused female grizzly bear mortality should not exceed 30 percent of the above total in any two consecutive years [11]. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believes these criteria have been met [11].

On March 29, 2007 the Fish and Wildlife Service declared the Yellowstone grizzly bear is a distinct population segment which is fully recovered and removed it from the endangered species list [11]. The decision has been opposed by many conservation groups and scientists who assert that the population is too small to be viable in the long-term, habitat and hunting/persecution threats will not be adequately addressed without Endangered Species Act protection, and global warming is devastating white-bark pine habitat [10, 11]. In response to a lawsuit, on Sept. 21, 2009, the U.S. District Court in Montana ordered the Yellowstone grizzly bear to be reinstated to the list of threatened species, which occurred on March 26, 2010 [15]. The 2011 Five-Year Review recommends delisting the Yellowsone DPS of the grizzly bear [12].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Grizzly Bear Fact Sheet. Accessed at <http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/species/mammals/grizzly/factsheetGrizzlybear111405.pdf>.

[2] Mattson, D.J., R.G. Wright, K.C. Kendall, and C.J. Martinka. 1995. Grizzly Bear In LaRoe, E.T., G.S. Farris, C.E. Puckett, P.D. Doran, and M.J. Mac, (eds). Our living resources: a report to the nation on the distribution, abundance, and health of U.S. plants, animals, and ecosystems. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Service, Washington, DC. 530 pp. Accessed at <http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/c032.htm>.

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Grizzly Bear Recovery. Mountain-Prairie Region, Endangered Species Program. Website <http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/species/mammals/grizzly/> accessed 3/2006.

[4]. Honnold, D.L. and L. Lucas. 2007. Notice of Violations of the Endangered Species Act in Designating and Delisting the Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Distinct Population Segment. 60-day notice of intent to sue filed on behalf of the Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council, Alliance for the Wild Rockies, Humane Society of the United States, Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project, Great Bear Foundation, and Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, April 2,2007.

[5] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Grizzly Bear (Ursus Horriblis). Website <http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/life_histories/A001.html> Updated 9/2005, accessed 3/2006

[6] Schartz, C.C., M.A. Haroldson, K.A. Gunther, and D Moody. 2002. Distribution of Grizzly Bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, 1990–2000. Ursus 13:203-212.

[7] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2000. News Release: Public to Review Strategy for Managing a Recovered Population of Grizzly Bears in the Yellowstone Ecosystem. Accessed at <http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/PRESSREl/00-05.htm>.

[8] Pease, C. and D.J. Mattson. 1999. Demography of the Yellowstone grizzly bears. Ecology 80(3):957-975.

[9] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Grizzly Bear Recovery: Yellowstone. Mountain-Prairie Region, Endangered Species Program. Website <http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/species/mammals/grizzly/yellowstone.htm> accessed 3/2005.

[10] NRDC. 2005. Grizzly Bears in Peril: Plan to remove protections for Yellowstone grizzlies threatens their long-term survival. Website <http://www.nrdc.org/wildlife/animals/bears.asp> updated 8/24/2005, accessed 3/2006.

[11] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Final Rule Designating the Greater Yellowstone Area Population of Grizzly Bears as a Distinct Population Segment; Removing the Yellowstone Distinct Population Segment of Grizzly Bears From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; 90-Day Finding on a Petition To List as Endangered the Yellowstone Distinct Population Segment of Grizzly Bears. March 29, 2007 (72 FR 14866).

[12] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Missoula, MT.

[13] Haroldson, M.A. and Frey, K. 2007. Grizzly Bear Mortalities. Table 13, Page 18 in C,C, Schwartz, M.A. Haroldson and K. West, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear Investigations: Annual Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2006. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, MT, USA.

[14] Haroldson, M.A. Assessing Trend and Estimating Population Size from Counts of Unduplicated Females. Pages 10-15 in C.C. Schwartz. M.A. Haroldson and K. West, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear invesrtigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2010. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, MT, USA.

[15] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. March 26, 2010. Reinstatement of Protections for the Grizzly Bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in Compliance With Court Order. 75 Fed. Reg. 14496.

Northern Great Plains piping plover (Charadrius melodus (Northern Great Plains DPS))

| Status: Threatened | Critical habitat: 9/11/2002 | Listed: 12/11/1985 | Recovery plan: 5/18/1999 |

Range: MT, ND, SD, NE, KS, CO, MN, IA, OK; SC, GA, FL, AL, MS, LA, TX, PR

SUMMARY

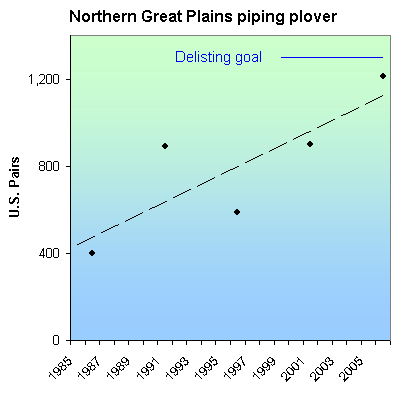

The Northern Great Plains piping plover was listed as endangered in 1986 due to threats from habitat loss, predation and disturbance. The number of Northern Great Plains piping plovers in the United States has increased from about 1,000 adults when ti was listed as an endangered species in 1985 to 2,959 adults in 2006.

RECOVERY TREND

In the Northern Great Plains, most piping plovers (Charadrius melodus) nest on the unvegetated shorelines of alkali lakes, reservoirs or river sandbars. The Northern Great Plains population is geographically widespread, with many birds in very remote places, especially in the U.S. and Canadian alkali lakes region, making population monitoring difficult.

The International Piping Plover Census is conducted every five years. The census found that the U.S. portion of the Northern Great Plains piping plover population decreased between 1991 and 1996, then increased in 2001 and again in 2006. In the United States in 1991, there were 2,023 adults and 891 breeding pairs. In 2006, there were 2,959 adults and 1,212 breeding pairs. The population of plovers in Canada increased in 1996, decreased in 2001, and then increased again in 2006. Overall, the number of Great Plains piping plovers has increased from approximately 3,500 birds in 1991 to approximately 4,600 birds in 2006 [1].

The recovery goal in the 1988 recovery plan is for 1,300 pairs in the Northern Great Plains that remain stable for 15 years including 60 pairs in Montana, 650 pairs in North Dakota, 350 pairs in South Dakota, 465 pairs in Nebraska, and 25 pairs in Minnesota [2].

The number of piping plover pairs in Montana increased from fewer than 20 pairs in 1986 to more than 100 pairs in 1992, then fluctuated around 60 pairs from 1994 to 2008. The number of pairs in North Dakota has fluctuated, but increased from around 300 pairs in 1986 to nearly 800 pairs in 2008. The number of pairs in South Dakota increased from around 100 pairs in 1986 to around 250 pairs in 2008. The number of pairs in Nebraska increased from around 100 pairs in 1986 to around 400 pairs in 2008. In Minnesota in 1986, there were approximately 11 plover pairs, but from 2002 to 2008 there were only one to two pairs. A few piping plover pairs are also found in Colorado, Kansas and Iowa. From 1990 to 2008, there were two to 18 pairs in Colorado, two to four pairs in Kansas, and four to seven pairs in Iowa [1].

Modeling strongly suggests that the piping plover population is very sensitive to adult and juvenile survival [1]. Therefore, while there is a great deal of effort extended to improve breeding success, to improve and maintain a higher population over time, it is also necessary to ensure that the wintering habitat, where birds spend most of their time, is secure. While the population increase seen in recent years demonstrates the possibility that the population can rebound from low population numbers, ongoing efforts are needed to maintain and increase the population. In the U.S., piping plover crews attempt to locate most piping plover nests and take steps to improve their success. This work has suffered from insufficient and unstable funding in most areas. In addition to habitat loss, human disturbance, and predation, emerging threats, such as energy development (particularly wind, oil and gas and associated infrastructure) and climate change are likely to impact piping plovers both on the breeding and wintering grounds [1].

CITATIONS

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2009. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 214 pp.

[2] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Great Lakes and Northern Great Plains Piping Plover Recovery Plan. 170 pp.

Whooping crane (Grus americana)

| Status: Endangered | Critical habitat: 5/15/1978 | Listed: 3/11/1967 | Recovery plan: 3/30/2007 |

Range: CO(m), FL(b), GA(m), IL(m), IN(m), KS(m), KY(m), MT(m), NE(m), ND(m), OK(m), SD(m), TN(m), TX(s), WI(b), WY(m) --- AL(x), AR(x), DE(x), DC(x), IA(x), LA(x), MD(x), MN(x), MS(x), MO(x), NJ(x), NC(x), OH(x), SC(x), UT(x), VA(x), WV(x)

SUMMARY

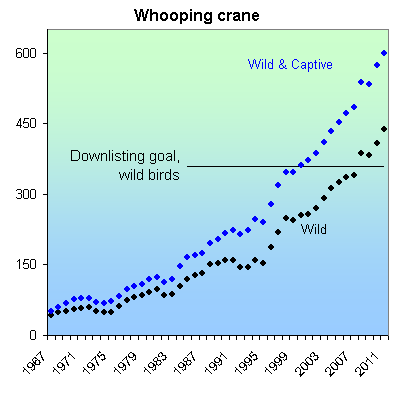

The whooping crane declined precipitously in the late 1800s and early 1900s due to hunting and habitat loss. It remains threatened by habitat degradation, collisions with power lines, and oil and gas development. When listed as endangerd in 1967, the whooping crane consisted of 43 wild and 7 captive birds. By 2011, it had grown to 437 wild and 162 captive birds.

RECOVERY TREND

The whooping crane (Grus americana) formerly occurred from the Arctic coast to central Mexico, and from Utah to New Jersey, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida [1]. In the 19th and 20th century, it's primary nesting area extended from central Illinois, northwestern Iowa, northwestern Minnesota, and northeastern North Dakota northwesterly through southwestern Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan and into east central Alberta. Wintering grounds and migration routes included much of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. As of 2012, whooping cranes nest in the wild at only three locations:

1) Wood Buffalo National Park and adjacent areas in Canada (this population winters in Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas),

2) Central Florida (this is an introduced, non-migratory population), and

3) Wisconsin (this population winters in Florida) [1].

An effort to reintroduce whooping cranes into the Rocky Mountain area by cross-fostering whooping cranes to sandhill crane foster parents was abandoned when the last whooping crane introduced into this population died in 2002 [1]. Captive whooping crane populations are maintained at the Calgary Zoo, International Crane Foundation, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, San Antonio Zoo, New Orleans Zoo, Lowry Park Zoo, and the Audubon Center for Research on Endangered Species.

Whooping crane populations in 1870 were variously estimated at 1,300 to 1,400 and 500 to 700 birds, but then declined precipitously due to hunting and habitat destruction [1]. Conservation efforts were able to maintain an extremely endangered but relatively stable population of 21 to44 birds between 1938 and 1966 [2]. When placed on the endangered species list in 1967, just 48 wild and six captive birds remained. In 1978, critical habitat was designated in parts of Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas, primarily on federal and state wildlife management lands [3]. Due to intensive habitat management, nest area protection, captive breeding and reintroductions, the population rose steadily to 513 (368 wild and 145 captive) birds in 2006. [2, 4]. Estimates as of May 2007 indicated a population decline of 31 birds [5], due in part to a storm that killed 17 of 18 birds being held at the Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge in Florida. The total population was 372 in 2000 and jumped to 599 in 2011 [8].

The 2003 draft international recovery plan sets forth two alternate criteria for downlisting the whooping crane to threatened status: 1) The Aransas-Wood Buffalo population must have at least 160 total birds with at least 40 productive pairs, and two additional separate self-sustaining populations must have at least 25 productive pairs and 100 total birds each. All three populations must maintain their status for a decade; or the Aransas-Wood Buffalo population must have 250 reproducing pairs and a total of 1,000 birds [1]. In either scenario, at least 21 productive pairs and 153 total birds must be maintained in captivity. Downlisting is estimated to occur in 2035. Delisting criteria have not yet been established.

Current threats to the species include low genetic diversity, loss and degradation of migration stopover habitat, construction of power lines, the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, degradation of coastal habitat, and in Texas, the threat of chemical spills [1].

CITATIONS

[1] Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane (Grus americana), Third Revision Albuquerque, New Mexico. 196 pp. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plans/2007/070604_v4.pdf

[2] Didrickson, B. 2011. Historic Whooping Crane Numbers: 1939-2011. International Crane Foundation. www.savingcranes.org/images/stories/site_images/conservation/whooping_crane/pdfs/historic_wc_numbers.pdf

[3] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1978. Determination of critical habitat for the whooping crane. 43 FR 20938.

[4] Stehn, T. 2007. Whooping crane numbers - November 22, 2006. Report provided by Tom Stehn, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, on May 16, 2007.

[5] Stehn, T. 2007. Whooping crane numbers - May 14, 2007. Report provided by Tom Stehn, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, on May 16, 2007.

[6] Dinnage, R.J. 2007. Federal whooping crane relocation program suffers setback. Land Letter, February 2007.

[7] U.S. Geological Survey. 2010. The Whooping Crane: Return from the Brink of Extinction. Http://whoopers.usgs.gov/publications/CraneInfoSheet_4pp.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2011.